According to DSM-IV, personality disorders represent long-standing and ingrained personality dysfunctions characterized by maladaptive, pervasive, and inflexible personality traits that deviate markedly from cultural norms, causing substantial distress or impairment. Personality disorders may manifest themselves in childhood and early adolescence and continue into adulthood.

Several studies have demonstrated that personality disorders are traceable to childhood and adolescent emotional and behavioral disorders. Lewisohn et al.

(1) found that adolescent disruptive, anxiety, depressive, and substance use disorders were associated with elevated personality disorder dimensional scores obtained at a 6-year follow-up in a young adult population. Cohen

(2) found that disruptive behavior disorders and affective disorders measured in childhood and adolescence increased the risk of personality disorder symptoms in young adulthood. Rey et al.

(3) demonstrated that disruptive behavior disorders in adolescence were associated with a wide range of personality psychopathology in adulthood. Young adolescent subjects who had had disruptive behavior disorders during adolescence showed high rates of all types of personality disorders (40% had a personality disorder at follow-up), although those who had had emotional disorders had a lower rate of personality disorders (12%) at follow-up. Other studies have demonstrated that adolescence is a period of risk for the onset of personality disorders

(4,

5). Hence, the evidence suggests that one should look for antecedents of personality disorders in childhood and adolescent disorders.

In spite of personality disorders representing a major health problem because of their prevalence

(5–

7), cost of treatment

(8), and the disability they cause

(9,

10), the empirical evidence on continuities between child and adolescent psychiatric conditions and personality disorders in adulthood is still limited, except regarding antisocial personality disorder

(10–

14). Moreover, the available studies offer mainly short follow-up periods that do not extend beyond early adulthood (19–25 years); thus, they fail to address the subjects’ full developmental potential and fail to demonstrate the stability of the disorder. On the other hand, available long-term follow-up studies of personality disorders fail to address adolescent populations

(15–

18).

Other substantial issues, such as the effect of gender on the development of personality disorders, have not been thoroughly elucidated yet, even though several authors have explored gender-related differences in personality disorders regarding prevalence

(5–

7,

19,

20), etiology

(21), and outcome

(15).

The aim of this study was to quasi-prospectively investigate continuities between emotional and disruptive behavior disorders in adolescence and personality disorders in adulthood. The study group consisted of reliably diagnosed adolescent psychiatric patients on the basis of medical records at their index hospitalization in adolescence and at a 28-year follow-up. The study will also address the effect of gender on the continuity between emotional and disruptive behavior disorders and personality disorders in adulthood.

To our knowledge, this is the first long-term follow-up study of a reliably diagnosed adolescent population with adult DSM-IV personality disorders as an outcome variable.

Based on existing research, we expected the following hypotheses to be confirmed:

1.

Adolescents with disruptive behavior disorders would be more likely to have personality disorders as adults than would adolescents with emotional disorders.

2.

Disruptive behavior disorders in adolescence would be associated with higher rates of antisocial, borderline, histrionic, and narcissistic (cluster B) personality disorders in adulthood than cluster A and cluster C personality disorders.

3.

Emotional disorders in adolescence would be associated with development of avoidant, dependent, obsessive-compulsive, self-defeating, and passive-aggressive (cluster C) personality disorders in adulthood.

Method

Subjects and Procedures

The subjects were recruited from a group of 1,018 adolescent patients, 553 males (54.3%) and 465 females (45.7%), who were consecutively admitted to the adolescent unit at the National Centre for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry in Oslo, Norway, from 1963 to 1978. Based on an examination of the Centre’s register of diagnoses, 93 patients with a diagnosis of organic brain syndrome and 35 patients with no definite diagnosis because of their short stay were excluded from the study. Except for three persons, no contact with the subjects had been maintained between admission in adolescence and follow-up in adulthood.

At the time of the follow-up (1998–2000), 143 subjects were deceased, 59 had emigrated, 17 could not be identified, and 24 had untraceable addresses, according to the Norwegian Central Register of Persons.

Thus, in all, 371 subjects were initially excluded from the study. The remaining 647 subjects were approached by mailed request and asked to voluntarily participate in a follow-up study. The study had been approved by the ethics review committee.

After the procedures had been fully explained, written informed consent was obtained from 194 (30%) of the subjects. Of these, 33 canceled their interview appointment. For unknown reasons, seven subjects did not show up for the interview. Fourteen subjects were unavailable at the address or the telephone number stated in the written informed consent and were thus impossible to trace. Two subjects were too disturbed to be interviewed. Four hundred and forty-five subjects did not respond to the request, and eight subjects expressed their disapproval of being contacted.

Finally, 148 subjects, 77 men and 71 women (14.5% of the original group) were interviewed. This represented 22.9% of those who were asked to participate in the study. Judged from the diagnoses in the register of the National Centre for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, these 148 subjects were diagnostically representative of the original study group. Only the diagnostic groups defined as having “neuroses” and “psychoses” were slightly overrepresented (57.8% in the interviewed group compared to 41.3% in the uninterviewed group) (χ2=15.11, df=1, p=0.01), and adolescents from the diagnostic group defined as being “substance abusers” were underrepresented in the final group (2.0% compared to 9.6%) (χ2=9.45, df=1, p=0.002). The subjects were also representative of the original group with respect to gender (χ2=2.64, df=1, p=0.20).

The follow-up interviews were carried out by M.I.H. All interviews were conducted in person except two, which were completed by telephone. The interviewer was blind to the subjects’ diagnoses from the National Centre for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. According to the subjects’ preferences, the interviews were conducted at their homes, at the University of Oslo, at mental health care institutions, or in prison. The average duration of each interview was 4.5 hours. Each follow-up interview consisted of administration of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders

(22) and the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality

(23), semistructured interviews that reliably assess symptom disorders and the 12 personality disorders described in DSM-IV. Thirty interviews were audiotaped for an assessment of interrater reliability of the diagnoses. Because the number of cases was too low for calculation of kappa values, an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was calculated for each cluster of personality disorders. An ICC of 0.83 was obtained for cluster A, 0.74 for cluster B, and 0.92 for cluster C. The median ICC was 0.76.

Thirteen subjects who received a diagnosis of schizophrenia at the follow-up were excluded from the present study. This was done because an assessment of personality disorders in a person with schizophrenia is difficult, if not impossible, because the diagnoses of personality disorders are based on the person’s usual way of behaving, independent of symptom disorders, medication, medical illness, or other confounding factors. Hence, a total of 135 subjects were included in the study.

Adolescent Diagnoses

Based on hospital records from the index hospitalization in adolescence, all 135 subjects were rediagnosed, according to DSM-IV axis I, by M.I.H., an experienced clinician. The records were made anonymous in advance by S.T. Thus, all ratings by M.I.H. were carried out as blind ratings. None of the authors had been involved in the treatment of the subjects. Complete medical records of high quality are imperative for diagnostic assessment based on a medical record. The National Centre for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry has been known for keeping thorough and detailed medical records due, in part, to the psychodynamic tradition prevailing at the time of our group’s admission and treatment, as well as to the generally long duration of hospitalization for the majority of the patients.

An interrater reliability study was carried out for 40 patients, yielding a kappa value of 0.72 for emotional versus disruptive behavior disorders. Once independent diagnoses were made, instances in which there was disagreement were reviewed by both clinicians, and a consensus diagnosis was made.

Adolescent diagnoses were divided into two groups: disruptive behavior disorders and emotional disorders. A distinction between these two groups is well established

(13). Two subjects with bipolar disorder, two subjects with a brief psychotic episode, and one subject with a learning disorder were excluded from the study because they could not be assigned to either of the groups.

Eighty-five subjects had received an adolescent diagnosis of disruptive behavior disorders: 67.7% of the men (N=42) and 63.2% (N=43) of the women. The group with disruptive behavior disorders included 70 subjects (82.4%) with conduct disorder, six (7.1%) with oppositional defiant disorder, five (5.9%) with psychoactive substance use disorder, three (3.5%) with adjustment disorder with disturbance of conduct, and one (1.2%) with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Forty-five subjects had received an adolescent diagnosis of emotional disorders: 32.3% (N=20) of the men and 36.8% (N=25) of the women. The group with emotional disorders included 17 subjects (37.8%) with anxiety disorders, 16 (35.6%) with depressive disorders, seven (15.6%) with eating disorders, four (8.9%) with somatoform disorders, and one (2.2%) with elimination disorder.

Forty-two percent of the subjects with disruptive behavior disorder had more than one disorder, with psychoactive substance use disorder being the comorbidity most often encountered (21.5% of the cases). Significantly more men than women had a comorbid psychoactive substance use disorder (χ2=13.56, df=3, p=0.003). Twenty-seven subjects (20.8%) had a comorbid emotional disorder, whereas 30 (23.1%) had no comorbid disorder. In case of comorbidity, a diagnosis of disruptive behavior disorder, the diagnosis of greatest clinical significance, was given hierarchical priority and served as a point of departure for assignment to the group with disruptive behavior disorder.

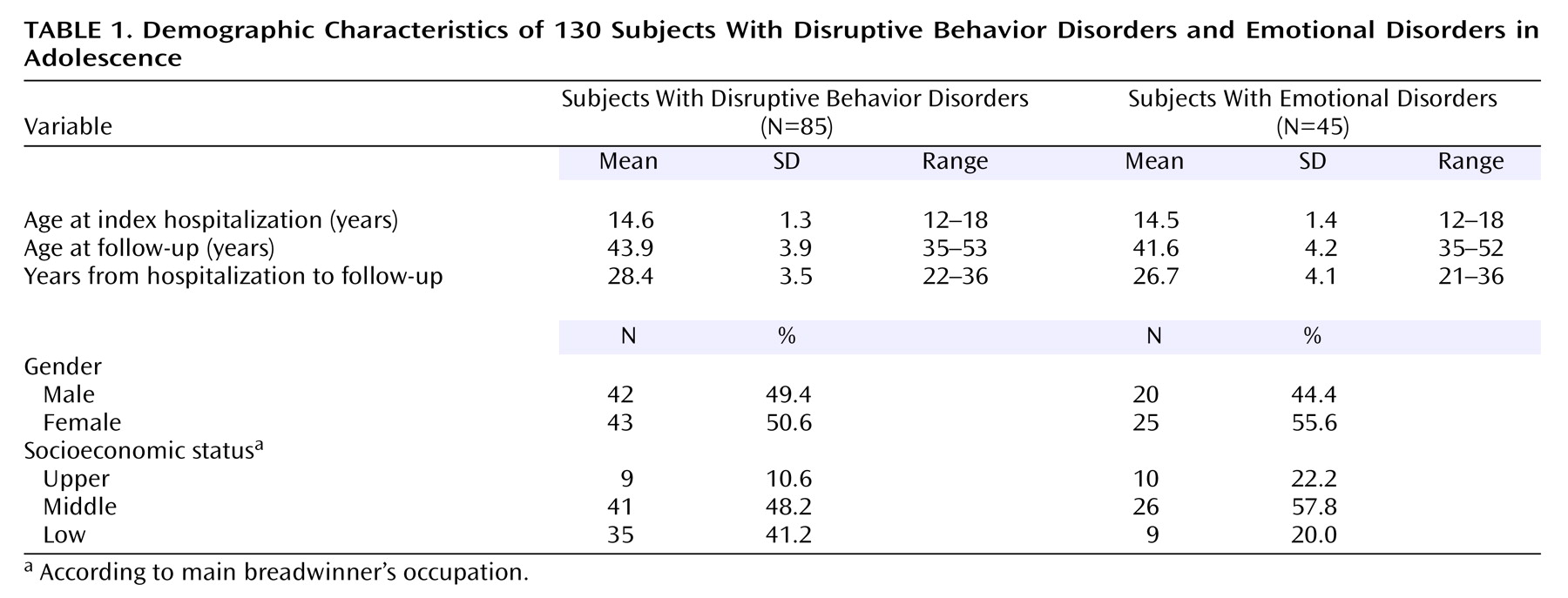

The subjects with disruptive behavior disorders did not significantly differ from the subjects with emotional disorders in terms of age, gender, age at index hospitalization, and age at follow-up. However, they differed in terms of social class because the majority of the subjects with disruptive behavior disorders came from families with low socioeconomic status (χ2=7.14, df=2, p=0.03).

The final study group (

Table 1) consisted of 130 subjects, 62 men (47.7%) and 68 (52.3%) women, with a mean age of 14.6 years (SD=1.3) at admission and 43.2 years (SD=4.2) at the follow-up. The mean length of stay during the index hospitalization was 29 weeks (SD=28, range=2–136). The mean interval between admission and follow-up was 27.9 years (SD=3.8, range=21–38).

Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed with logistic regression, allowing statistical control of confounding variables and minimizing the risk of false positive findings.

Separate analyses were performed for the following dependent variables: any personality disorder; any cluster A, any cluster B, or any cluster C personality disorder; and each specific personality disorder with more than five cases. Age at follow-up, gender, and disruptive diagnosis versus emotional adolescent diagnosis were used as independent predictors.

The reported odds ratios are those obtained in the models that showed a significant chi-square change when the corresponding predictor variable was added after the inclusion of the other variables.

Results

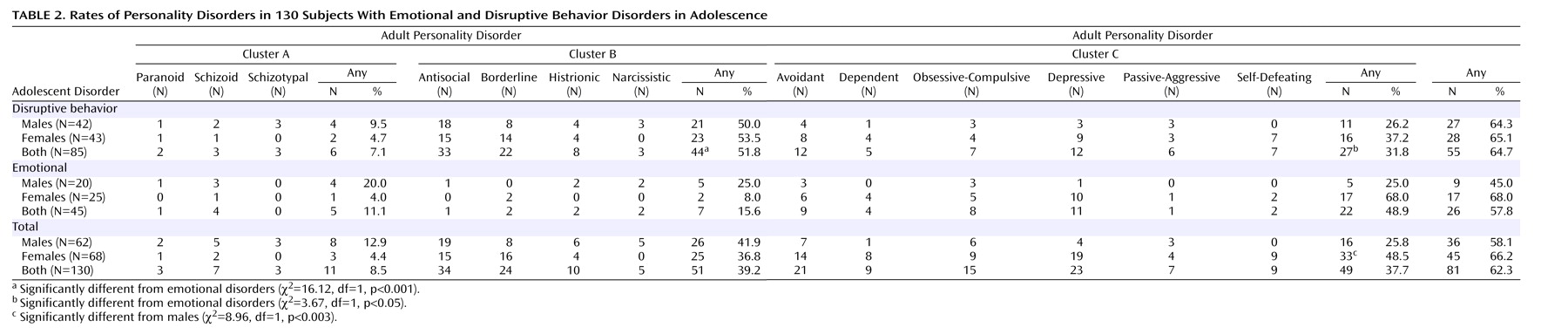

The overall results are summarized in

Table 2. Eighty-one individuals met the criteria for a diagnosis of personality disorder: 58.1% of the men (N=36) and 66.2% of the women (N=45). Thirty percent of those with a personality disorder had more than one concurrent personality disorder (N=39). Fifty-five (64.7%) of the adolescents with disruptive behavior disorders and 26 (57.8%) of the subjects with emotional disorders had at least one personality disorder at the follow-up. Adolescents with disruptive behavior disorders were significantly more likely to have a cluster B personality disorder at the follow-up than the adolescents with emotional disorders.

Antisocial personality disorder was the most common personality disorder found (N=34, 26.2%). All subjects with antisocial personality disorders had a diagnosis of conduct disorder in childhood or adolescence. Cluster C personality disorders were more common among women (N=33, 48.5%) than among men.

Logistic regression analyses for any personality disorders; any cluster A, any cluster B, or any cluster C personality disorder; and specific personality disorders in adulthood, with gender, age, and disruptive behavior disorders versus emotional disorders in adolescence as independent predictors revealed the following:

1.

Adolescents with disruptive behavior disorders were not more likely to have personality disorders in adulthood than adolescents with emotional disorders (odds ratio=1.82, 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.82–4.07).

2.

Adolescents with disruptive behavior disorders were more likely to have cluster B personality disorders in adulthood than adolescents with emotional disorders (odds ratio=8.62, 95% CI=3.14–23.69).

3.

As for specific personality disorders within cluster B, adolescents with disruptive behavior disorder were more likely to have antisocial personality disorder (odds ratio=75.92, 95% CI=8.45–682.09) and borderline personality disorder (odds ratio=8.93, 95% CI=1.87–42.70) in adulthood than adolescents with emotional disorders.

4.

In addition, age was an independent predictor of any personality disorders in adulthood so that older age at the follow-up was significantly associated with a lower likelihood for a personality disorder diagnosis (odds ratio=0.87, 95% CI=0.79–0.96).

5.

The same relationship between age and personality disorders was also observed for cluster B personality disorders (odds ratio=0.88, 95% CI=0.79–0.97) and, more specifically, for antisocial personality disorder (odds ratio=0.76, 95% CI=0.66–0.88).

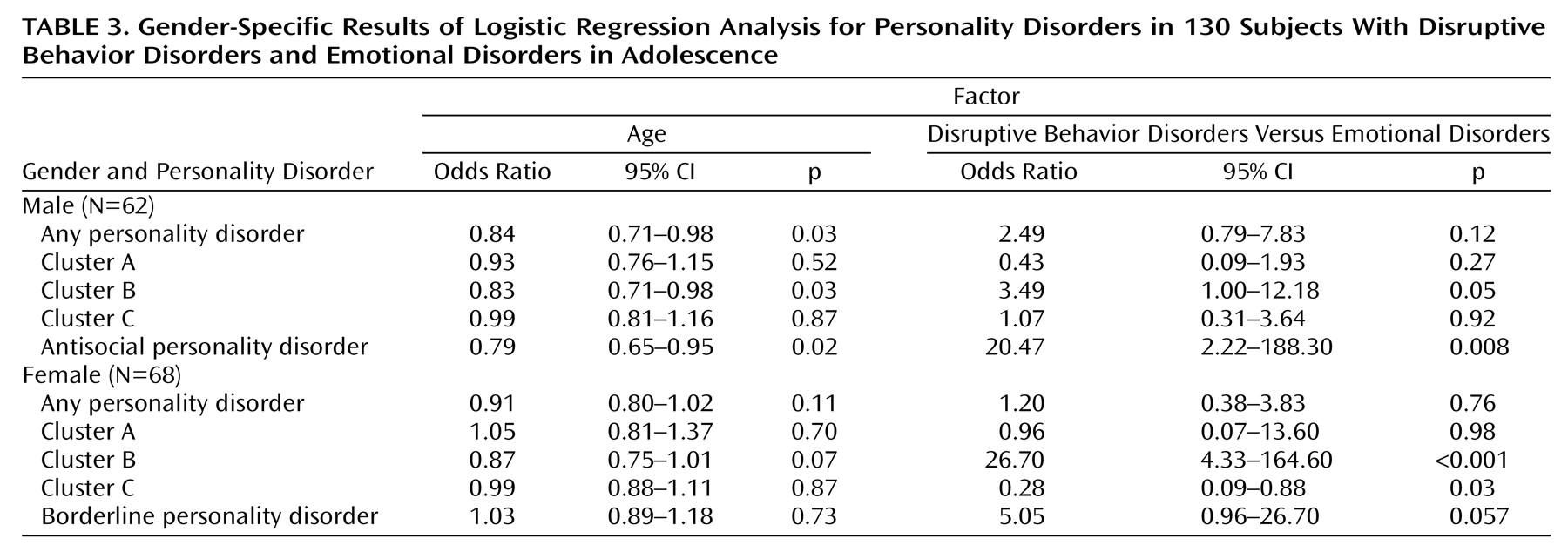

As

Table 3 demonstrates, further logistic regression analyses revealed that only male adolescents with disruptive behavior disorders were more likely than males with emotional disorders to have a personality disorder at the follow-up.

Disruptive behavior disorders in females were more strongly associated with a high risk of cluster B diagnoses than disruptive behavior disorders in males. Disruptive behavior disorders in adolescence were significant and independent predictors of antisocial personality disorder in men but not in women. Emotional disorders were significant and independent predictors of cluster C personality disorders in women but not in men.

In men, age was an independent and significant predictor of any personality disorders so that the older the age at follow-up, the lower the likelihood for personality disorders. The same relationship was also observed specifically for cluster B and antisocial personality disorder.

Discussion

Overall, the results of this study support the view that personality disorders can be traced back to emotional and disruptive behavior disorders in adolescence. In addition, our results clearly demonstrate that gender may play a moderating role in those continuities.

As expected and demonstrated by earlier findings

(3), disruptive behavior disorders were predictive of cluster B personality disorders. However, the men were not more likely than the women to have cluster B diagnoses. A similar finding has also been reported by Rey et al.

(3). Moreover, disruptive behavior disorders in females were actually more strongly associated with the risk of a cluster B diagnosis than disruptive behavior disorders in males. This finding was most likely influenced by diagnostic differences in the subjects with disruptive behavior disorders because significantly more females than males had a comorbid psychoactive substance use disorder. The impact of a co-occurring psychoactive substance use disorder on the continuity between adolescent disruptive behavior disorders and cluster B personality disorders in adulthood should, therefore, be addressed by future studies.

Our study demonstrated also that disruptive behavior disorders were an independent predictor of antisocial personality disorder in men but not in women. Numerous studies

(7,

24,

25) have suggested that males are more likely to develop antisocial personality disorder, whereas females are more likely to develop borderline personality disorder. In this context, our finding most probably reflects that the antisocial personality disorder diagnosis may be gender biased since DSM-IV criteria for antisocial personality disorder depend on a range of aggressive behaviors that are more prevalent in males than in females. Future research on the nosology of personality disorders should therefore address gender-related biological and sociocultural aspects of antisocial personality disorder and borderline personality disorder.

As demonstrated by earlier findings

(3), we found that cluster C personality disorders were more common in women than in men. In addition, we found that emotional disorders in adolescence were associated with cluster C personality disorders in women but not in men. This finding may reflect diagnostic differences between subjects who were included in the emotionally disordered group (most males had anxiety disorders, whereas most females had depression and eating disorders). Also, this result may represent a new finding suggesting that emotional disorders in adolescence may represent a point of departure to different forms of adult psychopathology for the two genders. It is also possible that the demonstrated continuity between adolescent emotional disorders and cluster C personality disorders in females could be due to socioculturally defined gender-specific reinforcement of the anxious, fearful, and worrying behaviors traditionally associated with female behavior.

Overall, however, adolescents with disruptive behavior disorders were not more likely than adolescents with emotional disorders to have personality disorders in adulthood. This finding does not support the notion of disruptive behavior disorders being associated with a particularly negative outcome regarding personality disorders

(3,

25). This finding may be due to group differences, because our group with disruptive behavior disorders included mainly subjects with conduct disorder, whereas the studies just mentioned included groups of subjects with ADHD, oppositional disorder, and adjustment disorder with disturbance of conduct. This finding may also reflect group characteristics. Because adolescents treated at the National Centre for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry represented the most gravely ill adolescents in Norway at the time, it is possible that the emotionally disordered group was biased toward extraordinary cases. However, these results may also represent a new finding that requires replications in future studies.

The overall interpretation of our results is subject to several limitations. First, our subjects were adolescent inpatients, and it is not known to what extent our findings can be generalized to other populations. Our findings may be biased toward more severe cases since adolescents treated at the National Centre for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry represented the most severely affected adolescents in Norway at the time.

Even though our group was representative of the original group, both clinically and with regard to gender, it is possible that the untraced subjects represented a selection-biased group because nonrespondents in personal follow-ups are often systematically different from responders. Hence, our findings need to be replicated by future studies.

However, several factors strengthen the validity of the reported findings. The study offers a follow-up interval of 28 years on average, which is very long compared to those of other studies. The majority of the subjects were in their mid-40s at the follow-up. It is therefore very likely that the level of personality functioning achieved by individuals of this age provided an accurate picture of their life potential.

Our study offers reliably assessed adolescent diagnoses and equally reliable diagnoses of personality disorders at follow-up. The study does not rely on retrospective accounts, thus avoiding recall bias.

Although our study demonstrated predictive relationships between adolescent emotional and disruptive behavior disorders and adult personality disorders, any causal conclusions must be considered tentative until there is a better understanding of the mechanism underlying these relationships. The pathways from adolescent disruptive and emotional disorders to adult personality disorders are influenced by complex and as yet unknown interactions among constitutional factors and extrinsic factors, such as stressors, trauma, family pathology, cultural and economic factors, and treatment

(26).

Nevertheless, this long-term quasi-prospective study validates findings from earlier short-term follow-up studies demonstrating that antecedents of personality disorders can be identified in adolescence in the form of emotional and disruptive behavior disorders. Gender differences revealed by this study suggest that continuities between adolescent disruptive behavior and emotional disorders and personality disorders in adulthood may proceed along different developmental pathways, resulting in different adult outcomes in men and women with similar adolescent psychiatric disorders. The nature of this relationship should be further addressed in future research.

Conclusions

Overall, with methodological limitations taken into account, our results support the view that personality disorders can be traced back to adolescent emotional and disruptive behavior disorders. The moderating effect of gender in cluster B and cluster C personality disorders suggests that biological and sociocultural factors may contribute to different adult outcomes in males and females with similar adolescent psychiatric disorders.