Vascular dementia is the second most frequent cause of dementia following Alzheimer’s disease

(1). Moreover, concurrent vascular pathology is present in 40% or more of Alzheimer’s disease patients

(2,

3), having an impact upon the clinical features

(4) and the threshold of Alzheimer’s disease pathology required for dementia to occur

(5). Cerebrovascular disease hence plays an important role in the majority of people with dementia. Yet, there are a number of mechanisms that may contribute individually or in combination to cognitive impairment in patients with cerebrovascular disease. They include large infarcts, multiple infarcts, strategic infarcts, and incomplete ischemic lesions of subcortical white matter

(3,

6–8).

In comparison with Alzheimer’s disease patients, those with a diagnosis of vascular dementia display a relative preservation of episodic memory but greater impairments of verbal fluency and frontal executive functioning

(9–

11). However, the pathological heterogeneity of vascular dementia causes considerable difficulty in defining the clinical syndrome and associated neuropsychological impairments and how these relate to the specific key types of vascular lesion

(7). Despite these difficulties, concepts pertaining to distinct subtypes of vascular dementia have been developed. The best established of these is subcortical ischemic vascular dementia, which describes vascular dementia related to small vessel disease that combines the overlapping clinical syndromes of “Binswanger’s disease” and “lacunar state”

(6,

12).

Subcortical ischemic vascular dementia is hypothesized to be caused by a loss of subcortical neurons or disconnection of cortical neurons from subcortical structures. The neuropsychological profile is described as characteristic of a dysexecutive syndrome (difficulties in goal formulation, initiation, planning, organizing, sequencing, set-shifting, and abstracting), with slowed cognitive and motor processing speed as well as more general attentional impairments

(3,

6,

12). It has further been proposed that memory deficits with impaired recall but relatively intact recognition are part of the syndrome.

This profile has emerged mainly from studies that have combined neuropsychological and neuroimaging data

(13–

17). In fact, many of these observations suggest that subcortical ischemic vascular dementia is a distinct clinical and neuropathological syndrome

(3,

6,

12). This is difficult to substantiate, however, since the majority of patients with dementia are in older age groups and at high risk of concurrent pathologies

(3,

6,

12).

Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) is a monogenic variant of small vessel disease caused by mutations in the

NOTCH3 gene

(18). Patients develop early and recurrent strokes as well as cognitive deficits that eventually lead to dementia

(19,

20). Advanced cases are clinically indistinguishable from sporadic “Binswanger’s disease”

(21). Similarly, histopathology shows a combination of small subcortical infarcts and incomplete ischemic lesions of the white matter and subcortical gray matter. CADASIL is hence an archetype of “pure” subcortical ischemic vascular dementia. Patients have a clearly defined vasculopathy, the diagnosis can be established with high accuracy in vivo (100% specificity), and, because of the younger age of these patients, concurrent pathology that could have an impact on cognition is unusual. In addition, mutational screening enables the reliable identification of presymptomatic or early symptomatic cases. Therefore, CADASIL provides a unique opportunity to address many of the issues related to subcortical ischemic vascular lesions and the concept of subcortical ischemic vascular dementia in rather the same way as studies of familial Alzheimer’s disease have provided valuable information about Alzheimer’s disease

(22,

23).

There are few specific studies that have reported neuropsychological findings in CADASIL subjects. In a series of eight mutation carriers without dementia, deficits were identified on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test and Trail Making Test in the majority of individuals

(24). Other small preliminary case reports have also suggested a prominent disturbance of frontal-executive performance

(25). A recent more systematic study compared cognitive performance in 34 CADASIL patients (13 prestroke and 13 poststroke patients and eight with dementia) and 15 comparison subjects

(26). Deficits in short-term memory (digits forward) and working memory (digits backward, Rey-Osterrieth memory test) were evident in the CADASIL patients who had not experienced a stroke. Among patients who had experienced a stroke, impairments in cognitive processing speed and set shifting (Trail Making Test part B) were identified. Recall, however, was still preserved even in the group with dementia. Given the prominence of slowed cognitive processing in patients with sporadic subcortical ischemic vascular dementia

(27,

28), it is slightly surprising that slowed processing speed was not an earlier feature in patients with CADASIL

(26).

The aims of the present study were twofold. First, we wanted to describe the profile of cognitive abnormalities in CADASIL subjects. Second, we wanted to test the hypothesis that cognitive impairment related to small vessel disease is characterized by a particular cognitive profile with executive and attentional dysfunction including slowed processing speed. To address these issues, we prospectively studied a large number of unselected mutation carriers and matched comparison subjects using a predefined protocol and comprehensive neuropsychological test battery. To provide additional information about the cognitive profile in early and advanced cases, we also undertook analyses of subsets of subjects grouped by global cognitive performance.

Method

Subjects

Sixty-five CADASIL subjects from 51 unrelated families were included in the study, with a diagnosis of CADASIL established by mutational screening of the

NOTCH3 gene

(29,

30). All patients were able to perform the testing procedure (no exclusions due to aphasia, motor deficits affecting the dominant hand, or severe dementia). None of the patients had experienced a stroke within the preceding 3 months, and there were no cases of alcoholism, drug abuse, or organic brain disease other than CADASIL. None of the patients was receiving cholinergic therapies. All CADASIL subjects underwent brain magnetic resonance imaging, which showed CADASIL-typical microangiopathic changes in the absence of territorial infarctions or other structural brain lesions.

The comparison group consisted of 30 healthy subjects (mostly spouses of CADASIL patients) who were matched in terms of age, gender, and educational level. Informed consent was obtained from all participants (or caregivers in the case of dementia) after the procedures of the study had been fully explained. The study was approved by the local ethics committee.

Data Acquisition

Subjects were prospectively enrolled at a single institution (Department of Neurology, Klinikum Grosshadern, Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich) between March 2002 and August 2003. All CADASIL subjects were examined by a trained neurologist. They all received a complete physical and neurological examination that included assessment with the NIH stroke scale

(31). Their dominant hand was established, and particular attention was paid to symptoms affecting their dominant upper extremity. Disability was rated with the modified Rankin scale

(32) and the Barthel Index

(33).

Neuropsychological testing was performed by a trained psychometrist in a quiet, well-illuminated room. All participants underwent detailed neuropsychological testing with the following battery of psychometric tests adapted for use with native German speakers:

1.

Global measures of cognitive function: Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)

(34), Mattis Dementia Rating Scale

(35), and the cognitive subscale of the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale (part of the Vascular Dementia Assessment Scale

[36]).

2.

Standardized assessment of vascular dementia: the cognitive portion of the Vascular Dementia Assessment Scale

(36), which includes the following items/tests: word recall, commands, constructional praxis (figures), delayed word recall, naming (figures and fingers), ideational praxis, orientation, word recognition, symbol digit modalities, digits backward, maze task, digit cancellation task, verbal fluency, remembering test instructions, spoken language ability, word finding difficulty, comprehension, and concentration/distractibility.

3.

Specific “frontal” tests with an emphasis on executive function including error monitoring and processing speed: Stroop test

(37) and Trail Making Test parts A and B

(38).

Data Analysis

To obtain an overview on the pattern of performance across cognitive processes and to address the issue of selectivity of deficits, we generated z scores using the mean values and standard deviations of the healthy group. The use of z scores enables direct comparison of performance in different cognitive domains.

To evaluate the pattern of cognitive performance in CADASIL subjects with mild to moderate impairment in global cognitive performance relative to those with severe impairment, subjects were divided into two groups according to their Mattis Dementia Rating Scale score using the widely accepted cutoff values (≤122 and ≥123). The Mattis Dementia Rating Scale score was used exclusively for classifying patients, i.e., it was not part of the data analyzed.

Group comparisons between CADASIL subjects and healthy subjects were undertaken using the Mann-Whitney U test. To account for multiple testing a p value <0.005 was considered significant. Statistical analysis was completed by using SPSS software version 12.01 for Windows.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

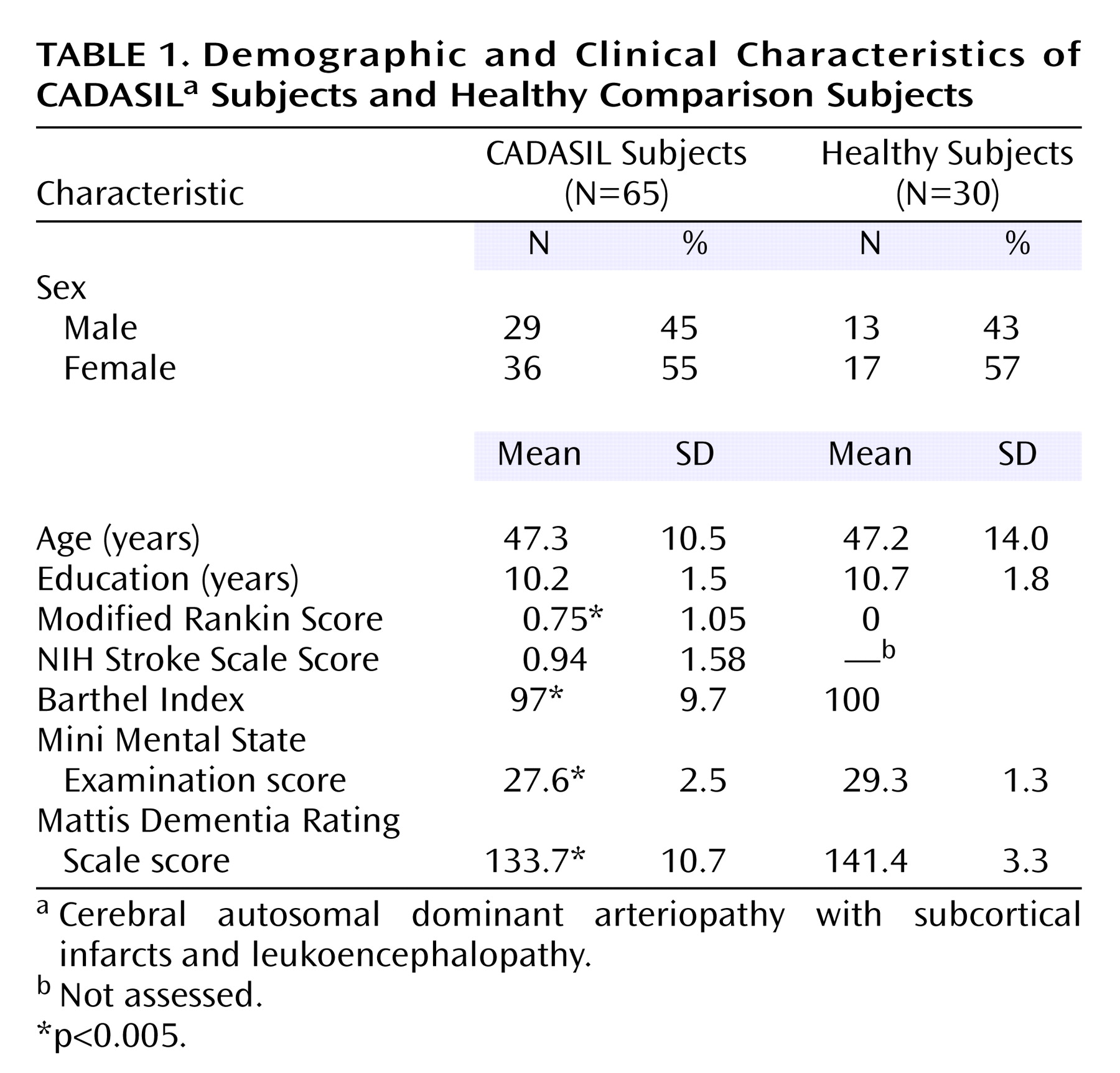

Demographic characteristics of the 65 CADASIL subjects and 30 healthy comparison individuals are illustrated in

Table 1. There was no significant difference between the two groups with respect to age, sex distribution, and years of education. At the time of investigation 56 (86%) of the CADASIL subjects had become symptomatic, and nine (14%) were asymptomatic. Forty-four (68%) individuals had experienced a transient ischemic attack or stroke. Manifestations further included migraine with aura (39%), psychiatric disturbance (mostly mild depression) (42%), and epileptic seizures (one patient). Global cognitive performance, as assessed by the MMSE and Mattis Dementia Rating Scale, was significantly more impaired in CADASIL subjects than comparison subjects (both p<0.005). Nine (14%) of the 65 CADASIL subjects had a Mattis Dementia Rating Scale score below the traditional cutoff value (≤122).

Cognitive Performance Profile

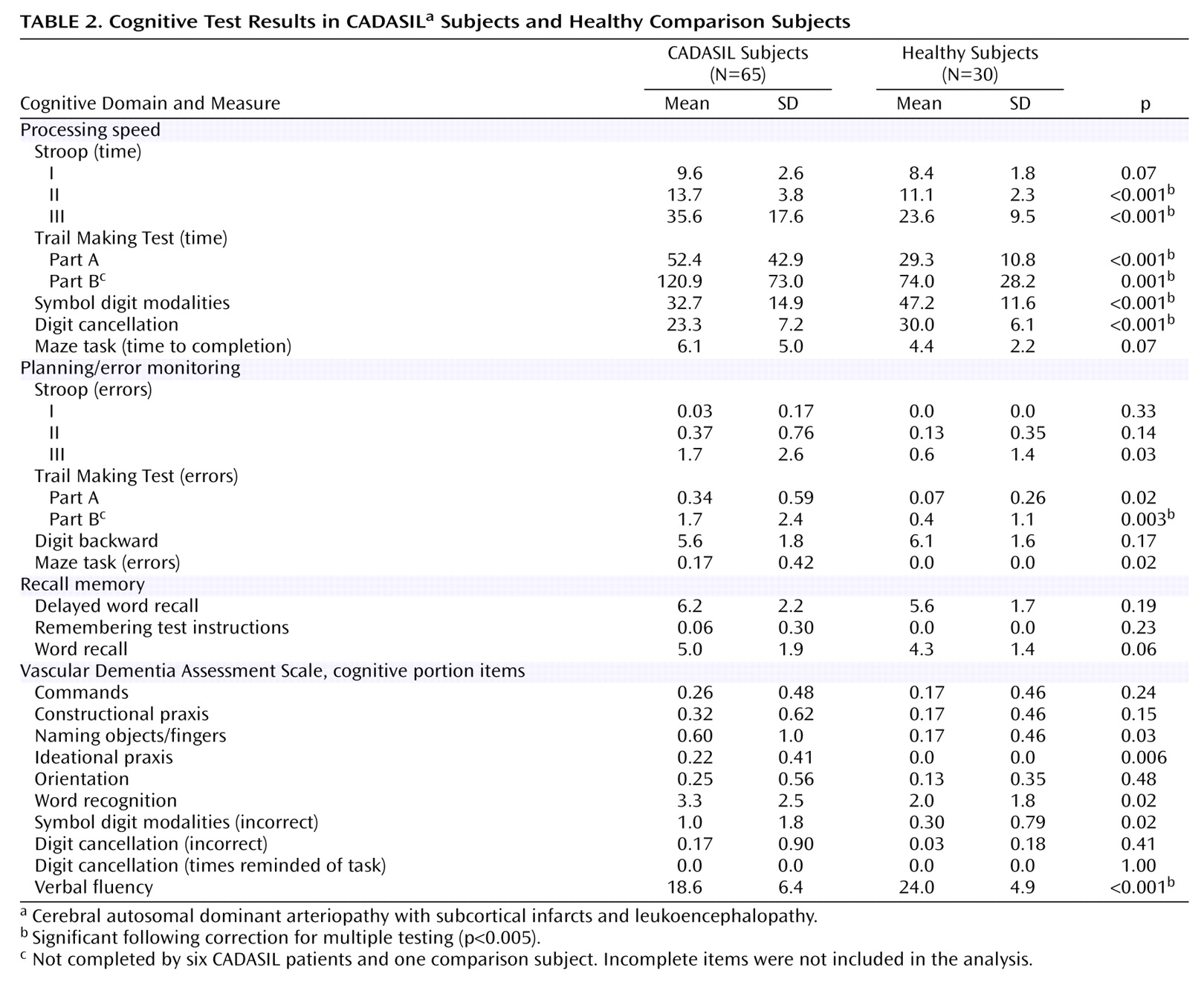

The cognitive evaluations of the CADASIL and comparison subjects are shown in

Table 2. CADASIL subjects were significantly more impaired than healthy subjects for all of the following items: the timed measures of the Stroop II, Stroop III, Trail Making Test parts A and B; the error measure of the Trail Making Test B; the correct responses on the symbol digit and digit cancellation task, and the verbal fluency task (all p<0.005).

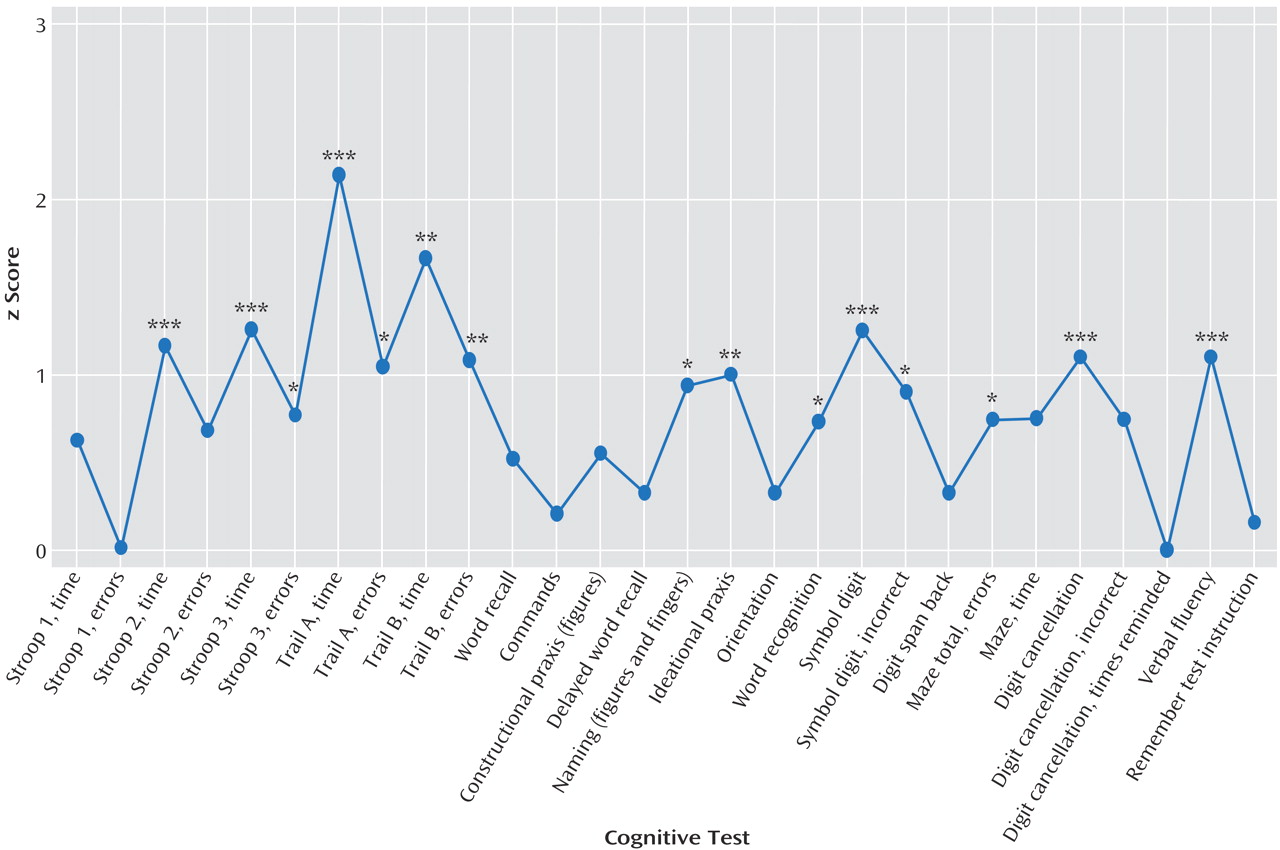

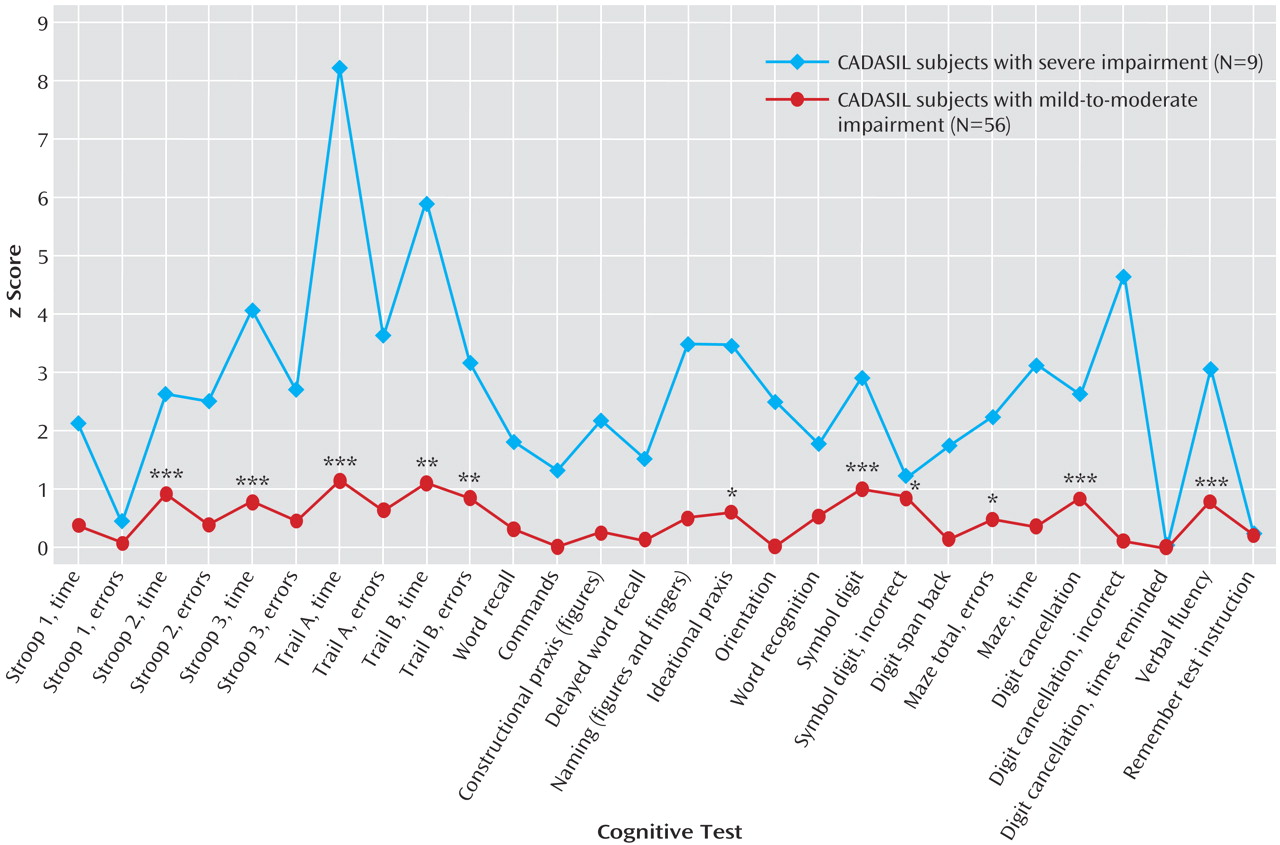

The differential magnitude of impairment in different aspects of cognition is profiled in

Figure 1, which displays the mean z scores achieved by CADASIL subjects relative to comparison subjects. Apart from the pronounced areas of deficit emphasized in

Table 2, impairments were also evident on ideational praxis, with some but less marked impairments of other aspects of performance. Memory (delayed recall, remembering test instructions) was relatively preserved. Orientation and receptive language skills (commands) were also largely unaffected. The same pattern was obtained if all subjects with neurological symptoms affecting their dominant arm were excluded (data not shown).

Subgroup Analyses

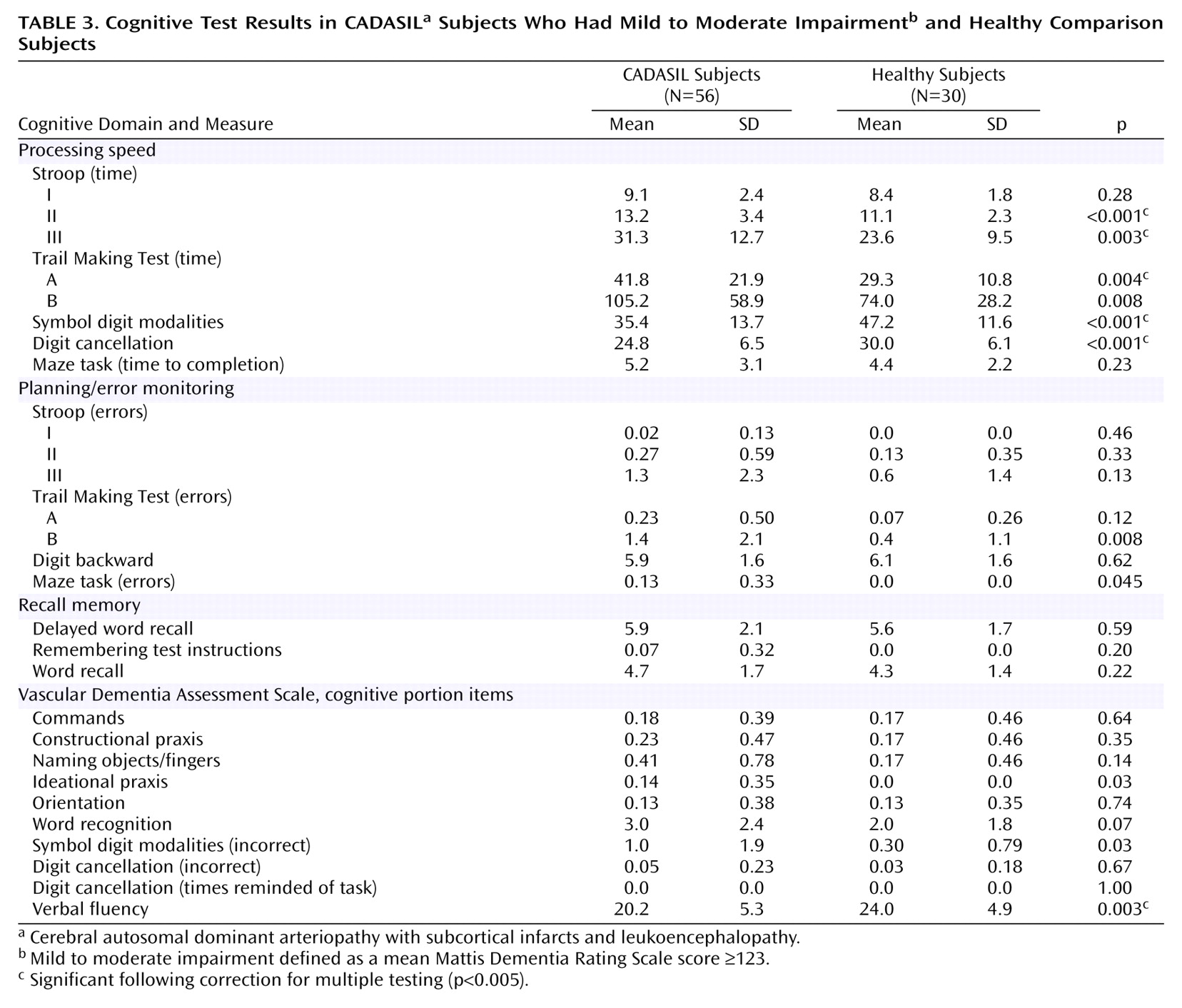

To explore the pattern of cognitive abnormalities in different disease stages, we looked at the effect of global cognitive performance as assessed by the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale on the different cognitive domains.

Figure 2 shows the z scores for CADASIL subjects with no or mild impairment of global cognitive performance (Mattis Dementia Rating Scale score ≥123, mean age=46.5 years, SD=10.6) and those with advanced deficits (Mattis Dementia Rating Scale score ≤122, mean age=52.8 years, SD=8.4). As shown in the figure, the profile of deficits was very similar in both groups. Also, all variables significantly different between the overall group of CADASIL subjects and healthy subjects (Stroop II [time], Stroop III [time], Trail Making Test A [time], Trail Making Test B [time], Trail Making Test B [errors], symbol digit [correct], digit cancellation [correct], and verbal fluency task) remained significant in CADASIL subjects with early cognitive impairment (Mattis Dementia Rating Scale ≥123) (

Figure 2 and

Table 3).

Discussion

In the largest study so far to examine cognitive function in CADASIL patients, significantly greater impairments were evident for the time and error measures of the Stroop and Trail Making Test tasks and other tasks of processing speed relative to age-matched comparison subjects. Thus, deficits of executive function and cognitive processing speed are emphasized as the characteristic cognitive hallmarks of the condition. We also observed significant decrements in ideational praxis, probably because of executive processes needed to plan and engage in abstract tasks

(39). Of importance is that this profile of deficits was evident even in patients with mild overall impairment. There was no significant difference from comparison subjects in performance on delayed recall tasks or orientation. The findings suggest that there is a clear and specific pattern of neuropsychological deficits in CADASIL patients that is distinct from that seen in other conditions with impairment of higher cortical functions, such as Alzheimer’s disease. In fact, our data suggest a double dissociation regarding processing speed and recall in CADASIL and Alzheimer’s disease, the latter of which is characterized by early deficits in recall but relatively preserved processing speed. These results suggest that sensitive tests of processing speed and error monitoring are likely to be particularly useful for the identification of early cognitive deficits and for monitoring change.

In the current study, timed tasks from the Stroop and Trail Making assessments were sensitive discriminators between CADASIL patients and comparison subjects and were internally consistent with other speed tasks such as the symbol digit and digit cancellation tasks

(40,

41), even in subjects with early cognitive impairment. There was also a consistent pattern of impairment in tasks of planning and error monitoring. This characteristic pattern of cognitive deficits is broadly similar to that reported in the only previous published study with a substantial cohort

(26). For example, both studies are consistent with regard to the Trail Making Test B error score and relative preservation of recall. However, there are several important differences. In the Amberla et al. study

(26), which included 34 CADASIL subjects and 15 comparison subjects, no significant differences were found in the timed component of the Trail Making Test part A, and differences in the timed component of the Trail Making Test part B were observed only for the poststroke patients. The studies are also discrepant with regard to the presence of deficits in verbal fluency and constructional praxis. These discrepancies may be explained in part by different methods of assessment. For example, the present study used a category fluency test, whereas Amberla et al. used a letter fluency task; previous studies support greater impairments of category fluency than letter fluency in vascular dementia

(42). Some of the other observed differences might further relate to differences between populations, such as a higher proportion of stroke cases in the current study. However, they may also be due to a type 2 error in the Amberla et al. study, which undertook the statistical evaluation based upon small patient subgroups that may have limited the power to detect differences.

CADASIL is an archetype of pure small vessel disease and hence pure subcortical ischemic vascular dementia. The profile of cognitive impairment identified in this study allows us to make some inferences about the core of the cognitive syndrome attributable to subcortical ischemic lesions. This is important because there is considerable heterogeneity of vascular pathology in dementia patients and frequent overlap with neurodegenerative changes, making it difficult to clarify the neuropathological substrates of specific aspects of cognitive dysfunction

(43). The observed pattern may be explained in large part by the disruption of specific prefrontal-subcortical circuits by ischemic lesions

(44–

48). These circuits involve multiple transmitter systems, offering potential therapeutic opportunities. Thus, for example, there is evidence for a localized cholinergic deficit related to the disruption of specific white matter tracts in CADASIL

(49). Such findings may be important for generating treatment approaches to CADASIL and a broader population of patients with subcortical ischemic vascular dementia.

The current study has several methodological strengths. First, neuropsychological evaluations were undertaken on a large cohort of patients with genetically proven CADASIL who were compared to a matched group. Second, we carefully controlled for a possible confounding effect of motor deficits affecting the dominant hand. Third, the battery of cognitive tests covered specific domains hypothesized to be impaired in subcortical ischemic vascular dementia and included instruments that are widely used in dementia studies. Thus, we consider it unlikely that the selection of tests biased the apparent profile of cognitive impairments. These methodological aspects, together with the internal consistency of the data, strongly indicate that the findings are robust.

In summary, the current study highlights a specific profile of neuropsychological deficits evident in CADASIL. This profile enables the construction of targeted cognitive test batteries relevant to clinical trials. Our data further provide information about the spectrum of cognitive deficits attributable to small vessel disease and subcortical ischemic lesions. Studies focusing on more targeted tests of executive function and memory may further enhance our understanding of subcortical ischemic vascular dementia.