Neuropsychological studies of major depressive disorder have demonstrated that depressed patients show impairment relative to healthy subjects on some tests of attention

(1), memory

(2), and emotional processing

(3). However, most of these studies assessed patients taking psychotropic medications, confounding interpretation of these results. For example, a previous study applying the Affective Go/No-Go Task of Murphy et al.

(3) found that

medicated depressed patients were impaired in their ability to shift attention from one affective valence to another, suggesting a mood-congruent affective bias for negative stimuli in major depressive disorder. The current study investigated performance on this task of

unmedicated subjects with major depressive disorder. The primary hypothesis tested was that unmedicated depressed patients would require less time to respond to mood-congruent sad words than to happy words, while healthy comparison subjects would show the opposite bias

(3).

Method

Twenty currently depressed subjects (10 men and 10 women) were selected who met DSM-IV criteria for recurrent major depressive disorder and had illness onset before age 40 years. Subjects had not received psychotropic medications within 3 weeks of testing. Four depressed patients were naive to psychotropic medications, and 11 had been medication free for 1 to 8 years. Depression severity was rated by using the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale

(4). Twenty medically healthy comparison subjects with no history of psychiatric disorders and no first-degree relatives with a psychiatric disorder were matched to the subjects with major depressive disorder for gender, age, and intelligence. Subjects were excluded if they 1) had ever met DSM-IV criteria for alcohol or substance dependence, 2) met criteria for alcohol or substance abuse within 1 year, 3) had a history of hypomanic episodes, 4) demonstrated full-scale IQ below 85, measured with the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence

(5), or 5) had clinically significant abnormalities on physical or laboratory examination. Written informed consent was obtained from each subject following full description of the study.

Three CANTAB subtests

(6) were used. The rapid visual information processing test, a continuous performance test, was used to evaluate attentional processing. The pattern recognition memory test was employed to assess encoding, retrieval, and recognition of nonverbal material. The spatial working memory test was administered to assess nonverbal short-term working memory.

The Affective Go/No-Go Task

(3) required subjects to respond to either happy or sad words. Eight word blocks, each containing 18 affectively valenced words (nine happy, nine sad), were presented. Single words appeared on a computer screen, and subjects were initially instructed to press the space bar for happy words (e.g., hopeful, serene) but not for sad words (e.g., glum, mistake). After two word blocks requiring responses to happy words, the instructions changed so that the space bar was to be pressed for sad words. Conditions were alternated in an HHSSHHSS pattern to create shift and nonshift response blocks. Each word was presented for 300 msec, followed by a 900-msec interstimulus interval.

Variables extracted from this task were target (omission) errors (e.g., failing to respond to sad words during sad word blocks) and distractor (commission) errors (e.g., responding to happy words during sad word blocks) during happy and sad word blocks, and during shift and nonshift blocks. Reaction times were recorded for correct responses.

Two-tailed repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were used to compare performances on the Affective Go/No-Go Task across groups. The within-group repeated measures were valence (happy versus sad word blocks) and shift (shift versus nonshift blocks). Two-way ANOVAs were used to compare performance between groups on the CANTAB subtests.

Results

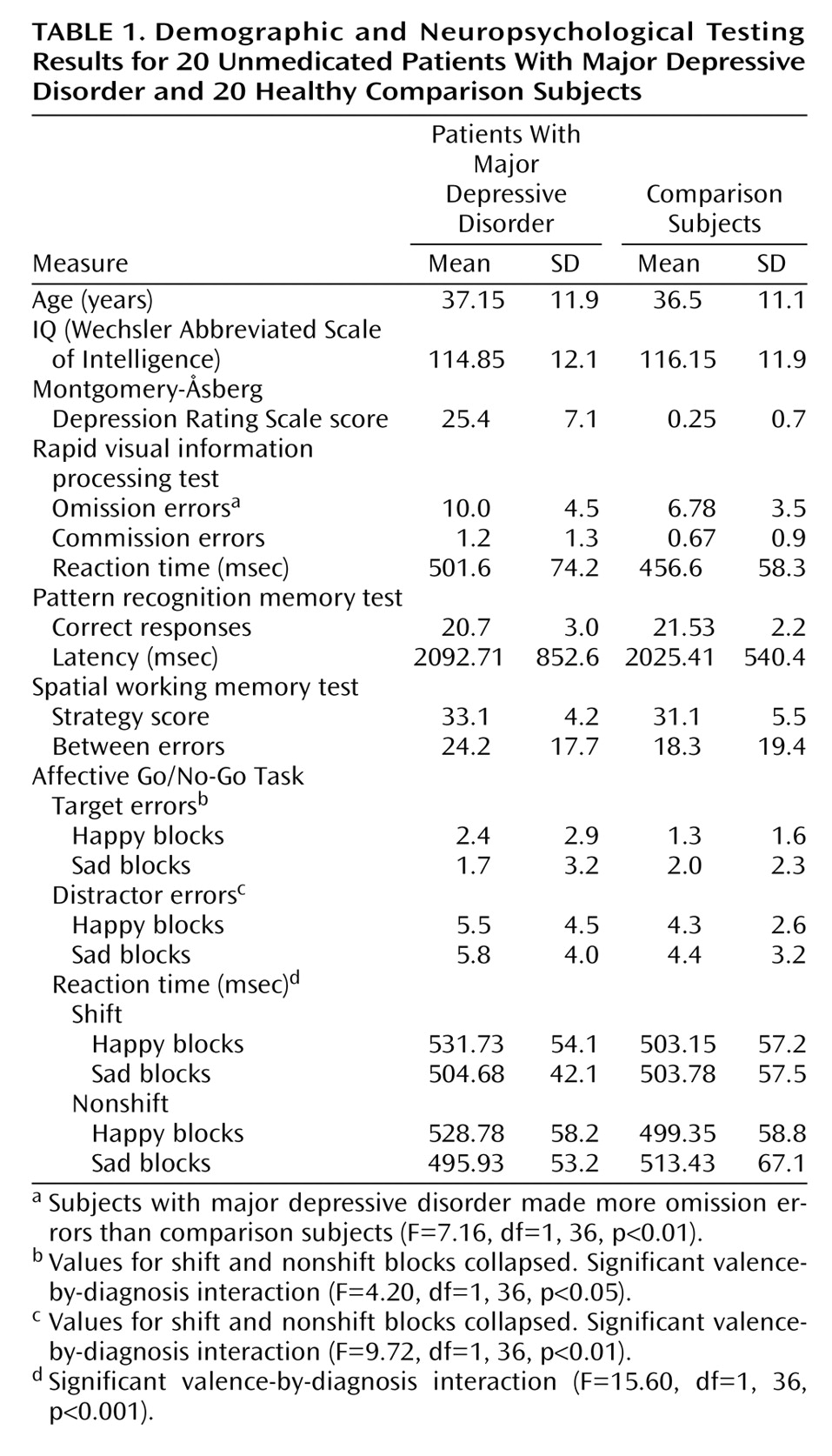

Mean age and full-scale IQ scores of the patients and comparison subjects are presented in

Table 1. Two-way ANOVAs indicated that the subjects with major depressive disorder made more omission errors than healthy subjects on the rapid visual information processing subtest (

Table 1).

Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA indicated a significant valence-by-diagnosis interaction for target errors (

Table 1); subjects with major depressive disorder made more target errors during happy than sad word blocks. Healthy subjects showed the opposite pattern, making more target errors during sad than happy word blocks. Both groups made more distractor errors during shift blocks than nonshift blocks (

Table 1). No significant diagnosis or gender effects were observed for distractor errors. Mean reaction time scores revealed a significant valence-by-diagnosis interaction (

Table 1); subjects with major depressive disorder required more time to respond to happy than to sad words, and healthy subjects required more time to respond to sad than to happy words.

Discussion

Depressed patients and healthy subjects showed different patterns of performance on the Affective Go/No-Go Task. Depressed patients made more omission errors when responding to happy than to sad words, and they responded more quickly to sad targets than to happy targets. Healthy subjects showed the opposite pattern for both error and response time variables. The mood-congruent processing bias was previously reported in medicated depressed patients, who also required more time to respond to positive words than healthy subjects

(3). Our results thus extend this finding in unmedicated depressed patients. Taken together, the two studies suggest preservation of a mood-congruent attentional bias despite pharmacological treatment.

The specificity of performance deficits on the Affective Go/No-Go Task was assessed with attention and memory tests. Attentional performance indicated more omission errors by depressed patients than by healthy subjects. No other significant differences between healthy subjects and depressed patients were found on CANTAB test performance, indicating that differences between groups on the Affective Go/No-Go Task were not accounted for by nonspecific cognitive impairment, although the number of subjects and statistical power were not large in this study. It has been assumed that cognitive deficits in depression are due to generalized cognitive slowing, but studies reporting such nonspecific impairment included depressed patients taking psychotropic medications. In contrast, studies of unmedicated depressed patients

(7,

8) indicated that cognitive deficits in depression are not associated with nonspecific changes in cognitive performance but, instead, implicate specific attentional processes.

On the Affective Go/No-Go Task, healthy subjects had longer latencies and made more omission errors in response to sad words than to happy words; these data suggest that the normative state is characterized by a positive bias. This phenomenon may conceivably confer resilience against the psychological impact of negative life events. In contrast, unmedicated depressed patients responded more slowly to happy than to sad words and made more omission errors during happy than sad word blocks. Large numbers of omission errors on the rapid visual information processing test suggest a generalized deficit in attention; therefore, this mood-congruent attentional bias occurs within the context of an attention deficit. However, the larger numbers of omission errors on the Affective Go/No-Go Task were not wholly attributable to an attention deficit, because omission errors were not extended across affective valence. Equivalent performance by depressed patients and healthy subjects in response to sad words but impaired performance in response to happy words by depressed patients indicates that salient stimuli affect attentional processing in depression.