Suicide rates in many Western countries have increased considerably in recent decades, causing much concern. Bereavement places people at a high risk of psychological and mental debilities, including mortality

(1). Suicide rates are higher among bereaved people (particularly early in bereavement) than for nonbereaved persons, and suicide is one of the most excessive causes of death among the bereaved

(2–

4). Thus, it is important to identify the mediators and moderators of suicidal behavior in bereavement. The suicidal ideation domain provides potentially useful information for understanding why bereaved persons attempt or actually commit suicide. Although few of those with suicidal ideation will act on their thoughts, ideation would seem a precursor to suicidal acts. Furthermore, suicidal ideation reflects thoughts of desperation in grieving that need to be comprehended. However, investigations of suicidal ideation in bereavement are rare.

Prigerson and colleagues examined relationships among “complicated grief,” depression, and suicidal ideation in bereaved persons, including young adults

(5) and elderly persons

(6). Complicated grief emerged as an independent predictor of suicidal ideation. Rosengard and Folkman

(7) investigated suicidal ideation among partners of men with AIDS. Over 50% experienced suicidal ideation; the rates were even higher in bereaved than in nonbereaved men. These studies suggest high suicidal ideation among the bereaved and associated complications in grieving. However, information is limited. The studies by Prigerson et al.

(5) and Szanto et al.

(6) did not focus on comparing suicidal ideation between bereaved and nonbereaved persons. Although the study by Rosengard and Folkman

(7) did so, many nonbereaved partners may have already been anticipating bereavement and even their own mortality. Overall, information is still lacking. Are the rates for ideation, as for suicide, really higher among the bereaved? Are there gender differences? Does social support reduce suicidal ideation, as Durkheim

(2) suggested?

Studies of social support in bereavement have not confirmed the stress-theory assumption that social support buffers persons against the deleterious effects of bereavement

(8). This finding is consistent with the attachment-theory assumption that loss of an attachment figure results in emotional loneliness (a sense of utter aloneness, whether or not the companionship of others is accessible), which cannot be reduced by the social support of family or friends

(9). We used data from an earlier study of ours

(8) to assess the impact of marital bereavement and social support on suicidal ideation and the mediating role of emotional loneliness.

Method

The participants were 30 widows and 30 widowers (mean age=53.05 years, SD=6.81) and 60 individually matched (by age, gender, socioeconomic status, and number of children), married individuals (mean age=53.75, SD=6.83) who were under retirement age. The prospective participants were sent a letter asking for their participation. Those who did not decline by mail or telephone were contacted a few days later to ask for an interview. To achieve a study group of 60 widowed individuals, 217 persons were approached. This rather low acceptance rate is typical for bereavement research.

The data for the present analysis, collected 4–7 months postbereavement, were obtained from questionnaires given personally to participants and returned by mail. We did not consider it ethically appropriate to ask recently bereaved spouses a battery of questions about suicidal ideation. Rosengard and Folkman

(7) asked a single question on a 3-point scale. We followed a similar procedure, deriving our measure from the Beck Depression Inventory

(10). Four statements (e.g., “I don’t have any thoughts of killing myself,” “I would like to kill myself”) were presented in an alternative-choice format.

Perceived social support was assessed with the Perceived Social Support Inventory, a 20-item questionnaire

(8) measuring four typical functions of social support (e.g., instrumental: “If I couldn’t go shopping, I’d have somebody to shop for me”; appraisal: “If I need advice on financial matters, I’d have someone to rely on”; emotional: “I have nobody to talk to about my feelings and problems”; contact: “I have hardly any friends who share my interests”). It has high internal consistency (alpha=0.90). Emotional loneliness was assessed by using two items: “I feel lonely even when I am with other people,” and “I often feel lonely” (alpha=0.78).

Results

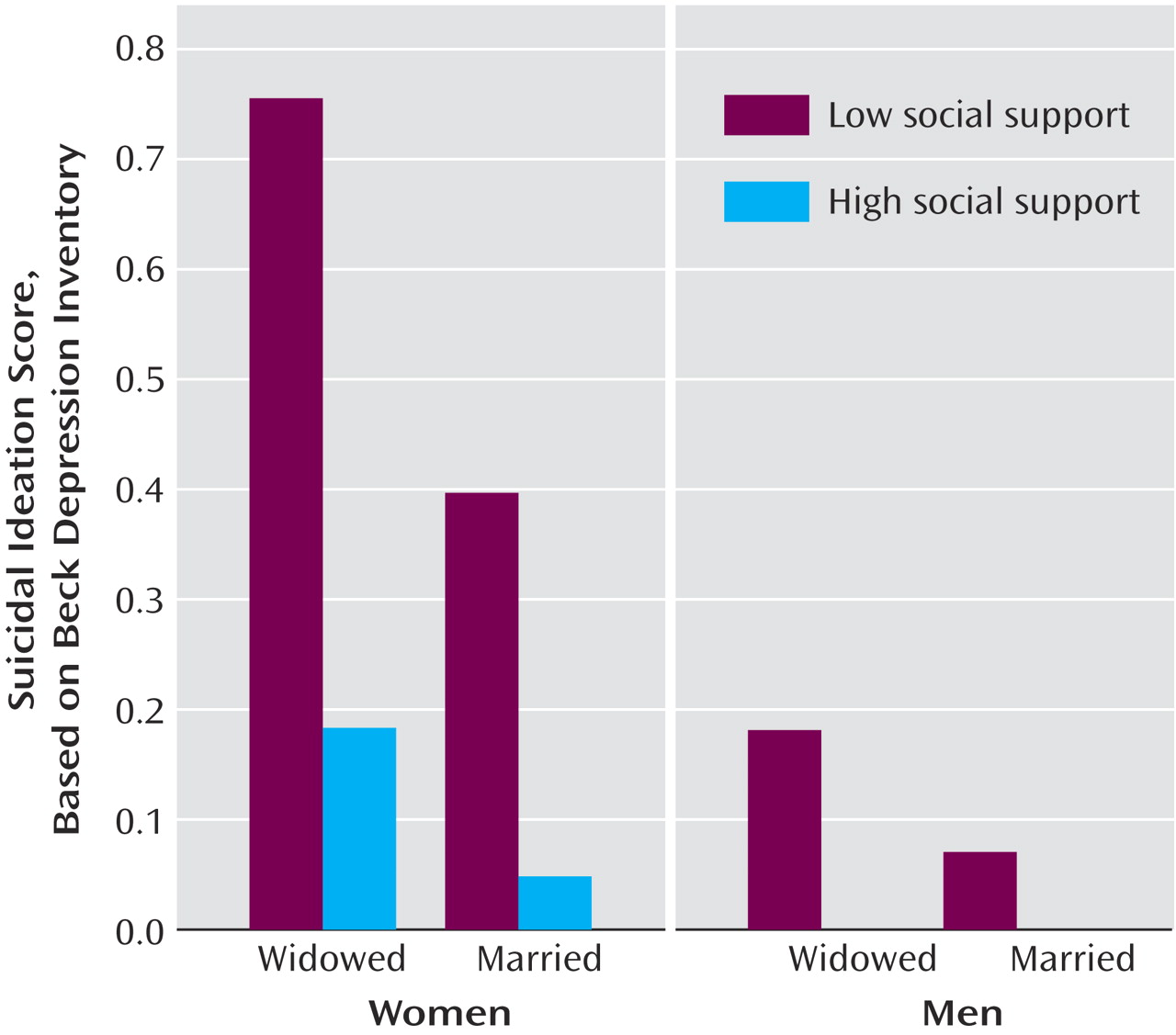

Figure 1 presents mean suicidal ideation scores of married and widowed individuals who rated above and below the median scores on the Perceived Social Support Inventory. A two-by-two-by-two (marital status-by-social support-by-gender) analysis of variance on suicidal ideation yielded a marginally significant main effect of marital status (F=3.16, df=1, 111, p<0.10), a main effect of social support (F=12.71, df=1, 111, p<0.01), a main effect of gender (F=11.58, df=1, 111, p<0.01), and an interaction of gender and social support (F=4.12, df=1, 111, p<0.05). The bereaved had higher levels of suicidal ideation than the married people; women had higher scores than men. High levels of social support were associated with lower levels of suicidal ideation. This effect was stronger for women than for men. The introduction of emotional loneliness as a covariate into this analysis eliminated the effect of bereavement on suicidal ideation (F=0.10, df=1, 107, n.s.), leaving all the other effects practically unchanged.

To examine the relationship of suicidal ideation to criteria for potential psychiatric diagnosis, suicidal ideation scores (for widows only) were analyzed by using the cutoff point on the Beck Depression Inventory for severe depression (score of ≥19). The mean suicidal ideation value with a severe depression score (mean=1.13, SD=0.99) was significantly higher than for those with a low depression score (mean=0.14, SD=0.35) (t=–5.46, df=57, p<0.001). Correlations between suicidal ideation and scores on the Beck Depression Inventory were much lower for those with a Beck Depression Inventory score <19 (Pearson correlation: r=0.28, p=0.05) than for those with a Beck Depression Inventory score ≥19 (Pearson correlation: r=0.92, p<0.01). Thus, suicidal ideation seems closely related to severe depressive symptoms among the bereaved.

Discussion

Loss of a partner, perception of low levels of social support, and being a woman were associated with increased suicidal ideation. Women are frequently found to have higher suicidal ideation and rates of suicide attempts than men, but our results indicated more excessive risk of suicidal ideation among widows than either widowers or nonbereaved women/men. This suggests that bereavement puts women at a worrisome high risk of suicidal ideation (particularly given the results showing a close relationship with severe depressive symptoms), although we must remember that—paradoxically—the prevalence of completed suicides is typically higher in (bereaved) men than in (bereaved) women

(11). Although lack of social support appears to have a more deleterious effect (its association with higher suicidal ideation for women than for men), again, there is no evidence of a buffering effect. Social support reduces suicidal ideation equally for both marital status categories.

The reason for the failure of social support to buffer the bereaved against the deleterious impact of loss of a partner became apparent from our analysis of covariance. Statistical control for differences in emotional loneliness eliminated the association between suicidal ideation and marital status, although it did not affect either the effects of social support or gender. This pattern is consistent with the attachment-theory assumption that the effects of loss of a partner and lack of social support are mediated by different mechanisms. Thus, uniquely, the impact of bereavement on suicidal ideation seems to be due to intense emotional loneliness, fitting the notion of “the broken heart.”