Psychotic disorders, particularly schizophrenia, are the most disabling of all mental illnesses. In fact, schizophrenia is included among the world’s top 10 causes of disability-adjusted life-years

(1). The majority of individuals with schizophrenia have a poor long-term outcome

(2–

4), which results in great personal suffering and societal cost. The largest expenditure for mental health in the United States is for schizophrenia

(5), with an annual cost of $32.5 billion

(6–

8). Most of this cost can be attributed to repeated hospitalizations following relapse

(9).

In an effort to improve the long-term outcome for individuals with schizophrenia, research has focused on early identification and intervention for psychosis. This approach to secondary prevention has been bolstered by findings that the sooner antipsychotic treatment is initiated after the emergence of psychosis, the better the clinical response (for example, see reference

10; see references

11 and

12 for reviews and references

13–

16 for exceptions). In addition, most clinical and psychosocial deterioration in schizophrenia occurs within the first 5 years of the onset of the illness

(11), suggesting that this is a critical period for treatment initiation

(17,

18). Thus, pharmacological and psychosocial treatment delivered during this critical period has been hypothesized to have a stronger impact than comparable treatment provided later in the illness

(17). Finally, there is a growing risk of treatment-resistant symptoms with each subsequent relapse

(19–

24). This is consistent with findings that show progressive loss of brain gray matter associated with recurrent episodes, suggesting that each relapse may reduce the individual’s capacity to respond to subsequent treatment

(25,

26). Early intervention may therefore reduce the risk of relapse and long-term disability associated with chronic schizophrenia

(27–

29).

Pharmacological Treatment of First-Episode Psychosis

Most individuals with first-episode psychosis are responsive to antipsychotic medication

(30). Remission of psychotic symptoms occurs in 50% of individuals with first-episode psychosis within the first 3 months after initiation of treatment with antipsychotic medication

(24,

31,

32), 75% within the first 6 months

(32), and up to 80% at 1 year

(31,

33–35).

The beneficial effects of antipsychotic medication on first-episode psychosis are tempered by the following issues: 1) individuals with first-episode psychosis are particularly sensitive to the side effects of antipsychotics, such as weight gain

(36,

37), 2) medication adherence is variable, with 6–12-month adherence rates in the 33%–50% range

(38,

39), 3) up to 20% of individuals with first-episode psychosis show persistent psychotic symptoms

(40), and 4) over 50% of individuals with first-episode psychosis report significant depression and/or anxiety secondary to the traumatic nature of psychosis

(41–

43).

In addition, despite initial symptom reduction, there is poor functional recovery following a first psychotic episode. Tohen et al.

(32) found that although approximately 75% of individuals with first-episode psychosis showed symptom remission at 6 months, most (79.8%) failed to show functional recovery during the same time period (see also reference

35). Individuals with first-episode psychosis tend to have impairments in general social functioning

(44,

45), quality of life

(46,

47), and occupational functioning

(48) despite clinical recovery. These functional impairments are present up to 5 years after illness onset even when optimal pharmacological treatment is provided

(49).

Psychosocial Interventions for First-Episode Psychosis

Clearly, pharmacotherapy alone is not sufficient to prevent relapses or assure functional recovery from acute psychosis. Thus, there is a growing interest in psychosocial interventions as a means of facilitating recovery from an initial episode of psychosis and reducing the long-term disability associated with schizophrenia

(50). Work in this area is still in its infancy, however. Treatment guidelines for first-episode psychosis, which include therapeutic engagement, targeting psychological and social adjustment, developing an active relapse prevention plan, and identifying barriers to treatment

(42,

51,

52), are based on clinical experience and not controlled research evaluating standardized psychosocial programs. There is a need for updated guidelines, informed by a rigorous review of available research.

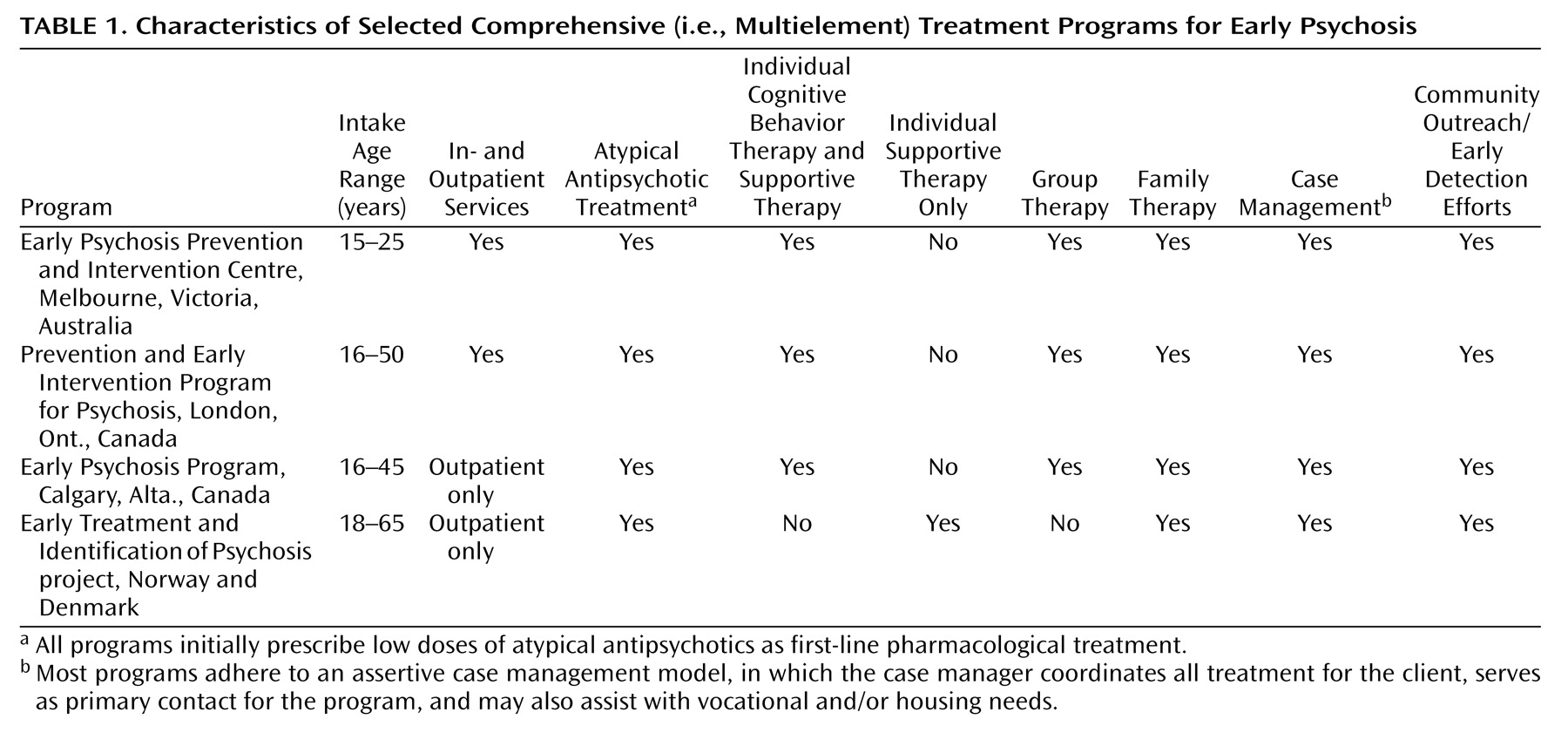

According to Edwards and colleagues

(53–

55), the literature on psychosocial interventions for first-episode psychosis can be conceptualized as constituting two broad categories: 1) studies evaluating comprehensive (i.e., multielement) interventions, which typically include community outreach/early detection efforts, in- and outpatient individual, group, and/or family therapy, and case management, in addition to pharmacological treatment (see

Table 1 for examples), and 2) studies evaluating specific (i.e., single-element) psychosocial interventions (e.g., individual cognitive behavior therapy). In this article we review the extant literature on psychosocial interventions for early psychosis in light of these two categories.

Search Strategy

A comprehensive search of the PsycINFO and MEDLINE databases (January 1983 to October 2004) was conducted by using the following terms: 1) “first-episode schizophrenia” and “psychosocial treatment” (or “therapy or treatment”), 2) “first-episode psychosis” and “psychosocial treatment” (or “therapy or treatment”), and 3) “early psychosis” and “psychosocial treatment” (or “therapy or treatment”). The results were evaluated for relevance, and only the studies evaluating psychosocial interventions for first-episode psychosis were selected for review. Specifically, we selected papers that quantitatively evaluated multielement interventions, individual cognitive behavior and supportive therapy approaches, and group and family interventions. The designs of the studies reported in the selected articles included experimental/randomized-controlled (i.e., comparing outcomes in randomized groups), quasi-experimental (i.e., comparing outcomes in nonrandomized groups), and single-group (i.e., evaluating change over time in one group of individuals receiving treatment). Studies that compared subgroups of patients within a particular intervention or program (e.g., patients with short durations of untreated psychosis versus patients with long durations of untreated psychosis) were excluded. Finally, to ensure that our search was as comprehensive and current as possible, we also conducted independent searches for recent publications by leading psychosocial researchers in the field of early psychosis (e.g., Addington, Birchwood, Edwards, Jackson, Lewis, Linszen, Malla, McGorry, Morrison, Tarrier). The findings of all of the selected studies are summarized in

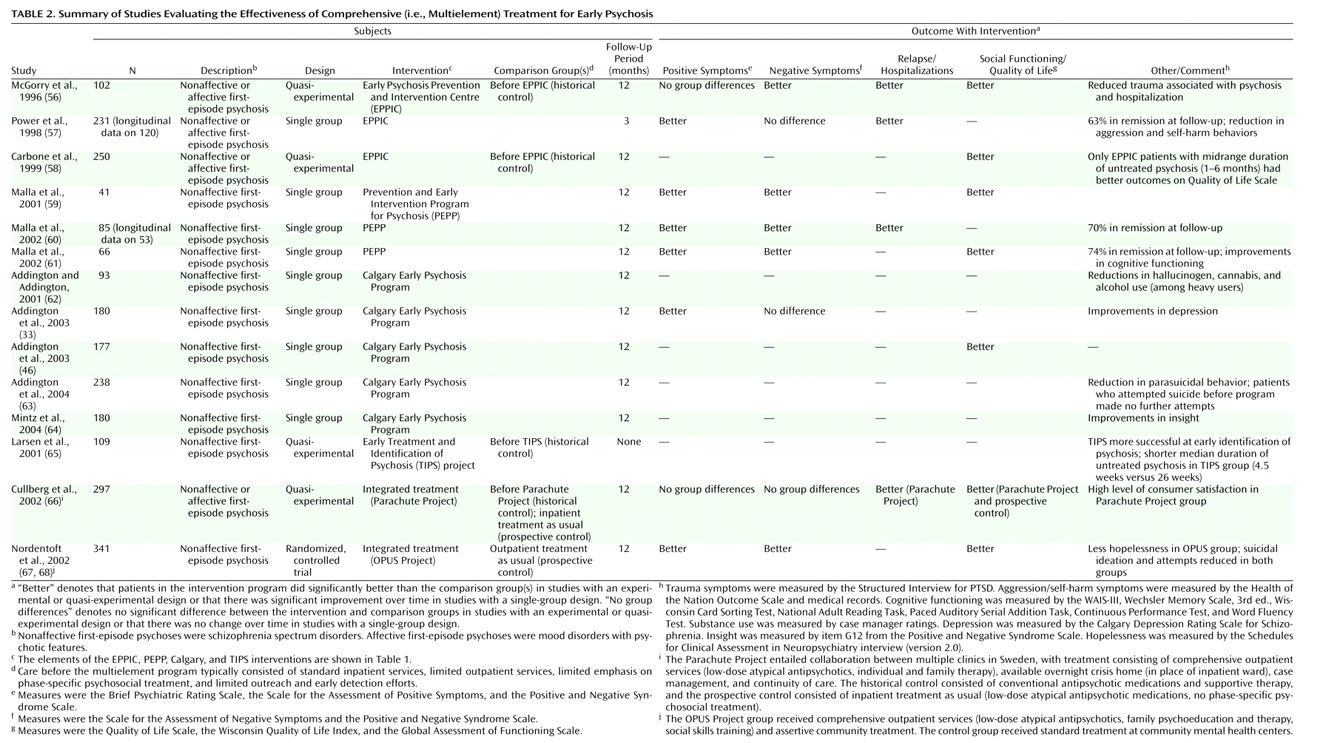

Table 2 (multielement studies) and

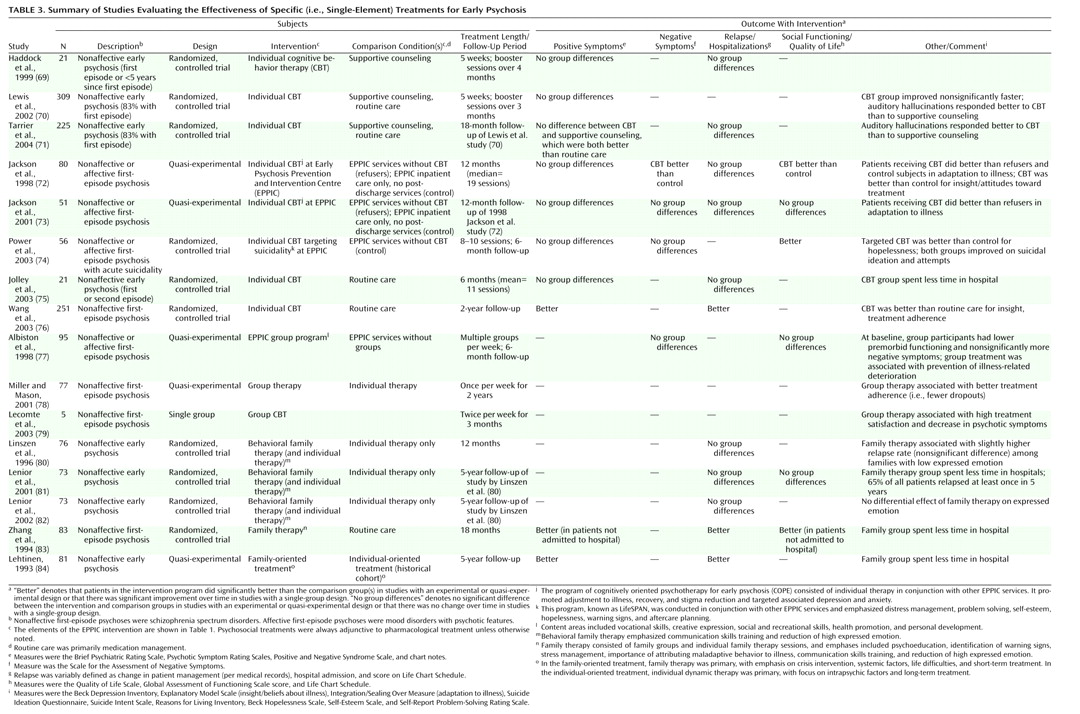

Table 3 (single-element studies).

Multielement Interventions

Multielement programs offer a comprehensive array of specialized in- and outpatient services designed for individuals experiencing first-episode psychosis, and they emphasize both symptomatic and functional recovery. Further, many of the issues that are particularly problematic among young individuals experiencing psychosis (e.g., substance abuse, suicidality, engagement with the mental health system) are addressed through a variety of targeted therapeutic approaches.

Table 1 provides general information about several multielement programs and their respective components (for a full description of these and additional programs, see reference

55).

The Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre in Australia is an exemplar of multielement care for first-episode psychosis and consists of a mobile assessment and treatment team; a 16-bed inpatient unit; in- and outpatient case management (including housing and vocational assistance); individual, group, and family therapy; pharmacological management (emphasizing low doses of atypical antipsychotic medication as first-line treatment); and specialized treatment for individuals with persistent psychotic symptoms. The Prevention and Early Intervention Program for Psychosis and the Calgary Early Psychosis Program are additional examples of established early intervention centers

(55). There have also been several large-scale efforts to evaluate the effectiveness of multielement treatment approaches for early psychosis delivered in the context of existing systems of care. For example, the Early Treatment and Identification of Psychosis project is a prospective, longitudinal 5-year study investigating whether early detection and treatment of psychosis can lead to better long-term outcomes

(85). A quasi-experimental design is comparing outcomes among individuals with nonaffective first-episode psychosis at three sites: 1) Rogaland, Norway, 2) Oslo, Norway, and 3) Ros-kilde, Denmark. All three sites offer multielement care, including individual supportive therapy, family work, case management, and pharmacological treatment; however, only the Rogaland site includes specialized early detection and community outreach efforts. Additional efforts to evaluate multielement models of care include the Parachute Project in Sweden, a collaboration among multiple psychiatric clinics to adapt and implement comprehensive first-episode services (i.e., low-dose atypical antipsychotic treatment, case management, individual and family therapy, and access to overnight crisis homes as an alternative to hospitalization)

(66), and the OPUS Project in Denmark, which evaluated the effectiveness of comprehensive, integrated care across a variety of treatment modalities (i.e., low-dose atypical antipsychotic treatment, assertive community treatment, family psychoeducation, and social skills training)

(67,

68). Indeed, the multielement model of care for early psychosis has been in existence for only a little over a decade but has already garnered significant research support across a variety of programs.

Examination of

Table 2 reveals that only one randomized, controlled trial of a multielement intervention has been conducted thus far

(67,

68). While additional programs are currently being evaluated in randomized, controlled designs, e.g., at the Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre

(55), the majority of published research in this area has utilized quasi-experimental and single-group designs to evaluate program effectiveness. Thus, the findings should be viewed with caution. Nevertheless, data emerging from these interventions have been encouraging.

A review of

Table 2 indicates that multielement interventions for early psychosis have been associated with symptom reduction and/or remission

(33,

56,

57,

59–

61,

68), improved quality of life and social functioning

(46,

56,

58,

59,

61,

68), improved cognitive functioning

(61), reduced duration of untreated psychosis

(65), low rates of inpatient admissions

(56,

60,

66), improved insight

(64), high level of satisfaction with treatment

(66), less time spent in the hospital

(56,

66), decreased substance abuse

(62), fewer self-harm behaviors

(57,

63,

67), and reduced trauma secondary to psychosis and hospitalization

(56). It should be noted that the foregoing results primarily refer to 1-year outcomes; longer-term benefits conferred by multielement programs have not been widely reported. Finally, a recent study suggests that these comprehensive and specialized first-episode services are likely to yield superior outcomes (e.g., shorter duration of untreated psychosis, fewer inpatient admissions, less time in the hospital) when compared with generic mental health services

(86).

Discussion

The findings reviewed suggest that adjunctive psychosocial interventions for patients experiencing early psychosis are beneficial across a variety of domains and can assist with symptomatic and functional recovery. Research on multielement interventions indicates that following an initial episode of psychosis, these comprehensive treatment approaches may positively influence short-term outcomes, such as clinical status and social functioning, as well as time spent in the hospital and likelihood of hospital readmission. However, as noted in another recent review of this area

(53), most of the research on multielement programs is based on quasi-experimental designs using historical

(56,

58,

65,

66) or prospective

(66) comparison groups or on single-group designs, which track the progress of one group over a specified period of time

(33,

46,

57,

59–64). Indeed, there is still a paucity of randomized, controlled research in this area; thus, these findings need to be interpreted with caution. Other methodological issues making interpretation of these results challenging include subject heterogeneity (e.g., affective versus nonaffective first-episode psychosis) and varying definitions for certain outcomes, such as relapse and remission, across studies.

One important caveat regarding multielement interventions is that the scope of these programs makes them difficult to implement on a widespread basis, particularly in countries whose public health care systems do not support the necessary infrastructure or do not recognize best treatment practices for early psychosis

(95). Indeed, given the wide range of services offered in these programs, it would be helpful to isolate the “effective ingredients” when evaluating a program’s utility. Understanding which elements are critical can help inform program development in areas currently lacking such specialized first-episode treatment services. Thus, the current findings in this area point to two important future research directions: 1) a greater number of randomized, controlled designs to provide a more stringent test of the efficacy of multielement programs and 2) utilization of research designs that will allow one to deconstruct the key ingredients of these programs and to determine the specific types of patients for whom these services are particularly beneficial. Single-element studies can be quite helpful in this regard.

With respect to research on single-element interventions, support for individual cognitive behavior therapy in early psychosis is modest yet encouraging, especially regarding symptom improvements (particularly positive symptoms), adaptation to one’s illness, and increased subjective quality of life (e.g., references

71–74). In addition, the majority of studies evaluating individual cognitive behavior therapy have used randomized, controlled designs. However, individual therapy has not been shown to be effective in reducing relapse or rehospitalization in early psychosis, and some findings suggest that early treatment gains may not be maintained over time.

No firm conclusions can yet be drawn from the literature on group and family therapies for this population. Group therapy is a widely used treatment modality for early psychosis, but to our knowledge, no randomized, controlled trials have been conducted. Research findings on family therapy in early psychosis have been mixed, with some studies documenting benefits with respect to symptoms, social functioning, and likelihood of rehospitalization (e.g., reference

83) and other studies having less favorable results (e.g., reference

80). One possible interpretation of these findings is that family interventions are indeed beneficial to individuals with early psychosis although they may not add significant benefit above and beyond concurrent individual therapy. Additional well-controlled research is needed to clarify the impact of family and group therapy in first-episode psychosis.

In general, while the research done to date on specific (i.e., single-element) psychosocial treatments for early psychosis is promising, there are few robust findings. Many of the aforementioned single-element studies were conducted in the context of large multielement programs (e.g., references

72–74); it is therefore difficult to yield robust additive effects of a specific intervention, when such a large degree of improvement is likely due to the impact of the program as a whole. Further, as with the literature on multielement treatments, significant obstacles to drawing broader conclusions with respect to specific psychosocial treatments for first-episode psychosis include the paucity of well-controlled studies, as well as methodological variation among studies (e.g., study group composition, definitions for remission and relapse).

Future work should take an increasingly integrative approach to psychosocial treatment, drawing on a variety of empirically validated treatment approaches to address the variety of challenges that individuals with first-episode psychosis experience (e.g., positive and negative symptoms, medication adherence, substance use, functional impairments). Indeed, future studies should place more emphasis on measuring functional recovery (i.e., social, work, and school functioning, recreation, and social relationships

[96]) both during and after treatment. Despite demonstrated short-term benefits, the ability of psychosocial interventions delivered early in psychosis to effect long-term improvement, particularly with respect to social/occupational disability, is still unknown. Additional longitudinal research is needed to shed light on this question.

Some findings suggest that many of the initial benefits achieved in treatment may not be maintained over time in patients with first-episode psychosis

(97). This may be addressed through greater efforts to improve ongoing engagement with available services (which is a significant challenge in the field of early psychosis [e.g., reference

98]) and to lengthen the duration of active interventions, if necessary. Studies of individuals with chronic schizophrenia suggest that longer-term treatments are often associated with more favorable outcomes

(99). In addition, naturalistic studies of psychological treatments for a variety of nonpsychotic disorders have demonstrated that patients tend to show greater degrees of improvement with longer periods of treatment

(100). Clinicians and researchers alike should utilize these findings to inform the delivery of psychosocial interventions in early psychosis. Ideally, these efforts will be successful at improving both short- and long-term outcomes, thus reducing the morbidity and mortality so often associated with this devastating illness.