Selection of Studies

To maximize the likelihood of obtaining all relevant published research, we used a three-phase search process. First, we identified studies using a manual search of 19 high-quality, high-impact journals that routinely publish efficacy research, including research on PTSD (e.g., The American Journal of Psychiatry, Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology). Next, we conducted an exhaustive computer search of PsychInfo and Medline, using the key words “PTSD” and “Posttraumatic.” Last, we manually reviewed prior meta-analyses and reviews for studies not obtained using the first two procedures.

We included studies published in the years 1980–2003. Inclusion of only published studies (rather than unpublished, “file-drawer” studies

[20]) in this study as in past reviews and meta-analyses means that the findings can only be generalized to published research and therefore could potentially inflate estimates of efficacy. We did this because our prior research using this method with other disorders has identified a number of limitations of the treatment literature we have meta-analyzed, leading to conclusions somewhat at odds with prior reviews. We thus wanted to reexamine data similar to those examined in prior reviews and meta-analyses, from which conclusions about efficacy and treatment of choice have been drawn, without the possibility that any findings reflect sample differences or biases on our part.

To be included, we required studies to meet the following criteria. 1) The study had to test a specific psychotherapeutic treatment for PTSD for efficacy against a control condition, an alternative credible psychotherapeutic treatment, or a combination of two or more of the above (relaxation and biofeedback were included as control conditions, not as primary treatments tested, in accordance with the stated goals and theoretical descriptions of the treatments in the primary articles reviewed). 2) The study had to use a validated self-report measure of PTSD symptoms or a validated structured interview administered and scored by an evaluator blind to treatment condition. In studies reporting both a valid self-report measure and an interview assessment for which the evaluator was not blind, we used only the self-report data in our analyses. 3) The study had to be experimental in design, including random assignment of patients to condition and standardized treatment. 4) Enough patients had to be included to randomly assign 10 patients to each experimental group. We chose a priori to exclude studies with fewer than 10 patients per condition because of methodological concerns about studies that build in too little power to detect effects and because of concerns about maintaining the blind with such small Ns. 5) The study had to be reported in English. We excluded studies that reanalyzed data already included in the meta-analysis unless they provided new data. We included only studies that used adult patients and that examined treatment of PTSD proper (rather than acute stress disorder, preventive programs such as debriefing in the wake of a traumatic event, etc.). All decisions of this sort were made a priori, before examining any individual studies.

Procedure

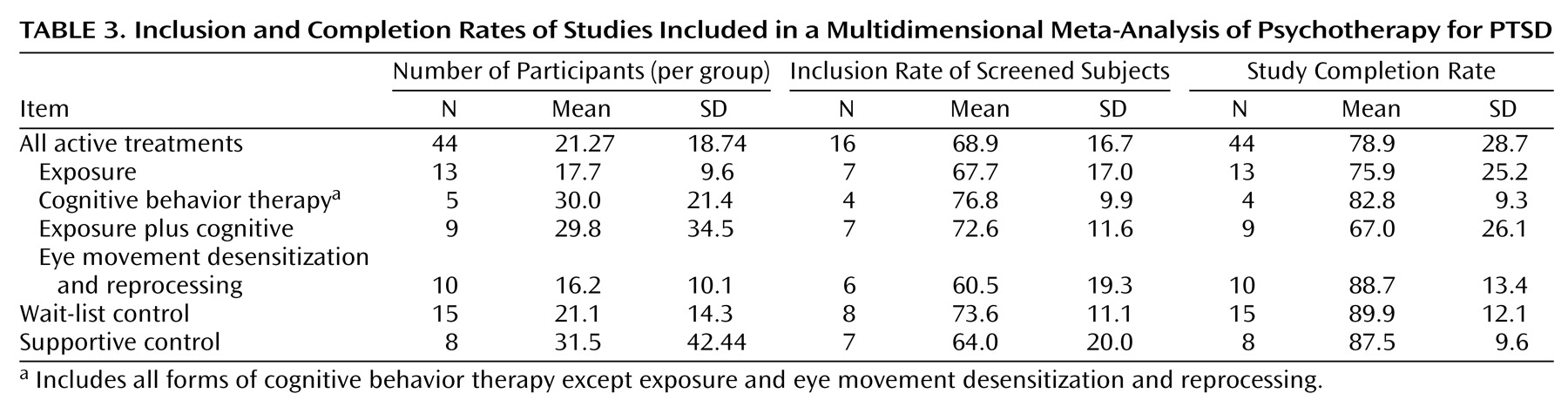

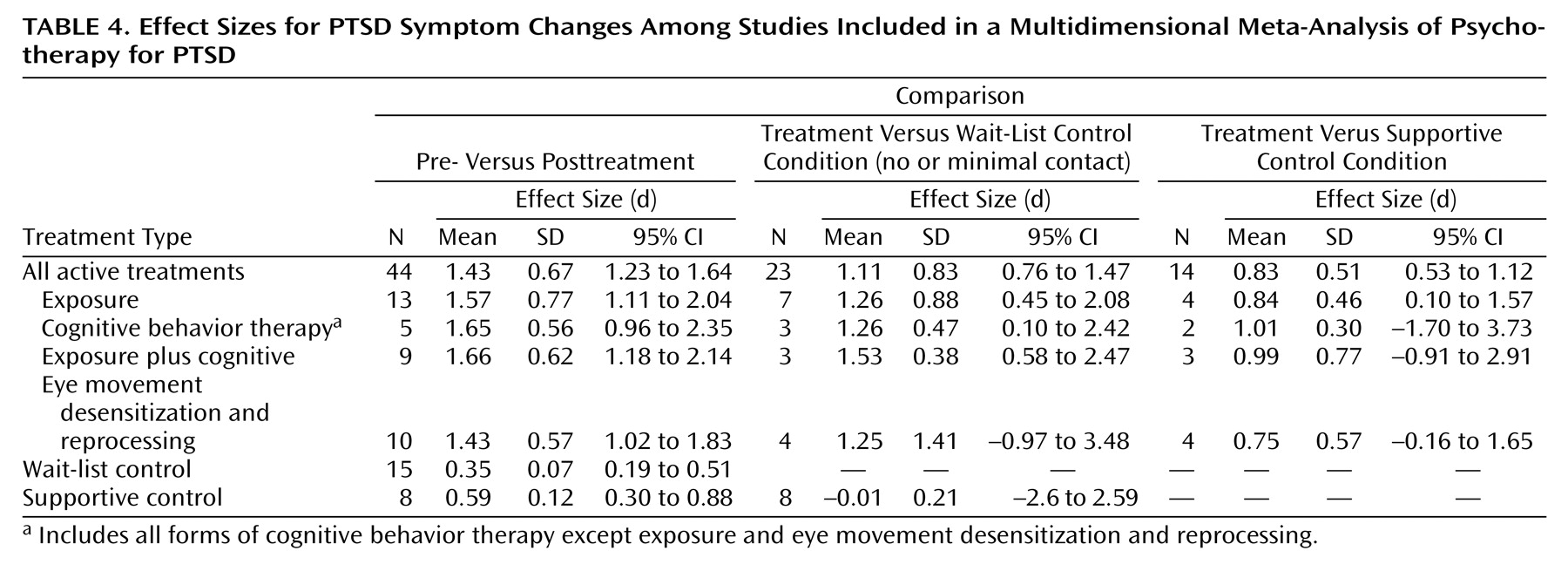

We assessed the following variables: number of participants, participant inclusion rate (out of those screened for participation), number of exclusion criteria, study completion rate, effect size (for both treatment versus control conditions and pre- versus posttreatment), rate of diagnostic change (i.e., patients no longer meeting criteria for PTSD), improvement rate (for study completers as well as the intent-to-treat study group), and mean posttreatment symptom level. We assessed the same variables at follow-up intervals of 6 months and beyond.

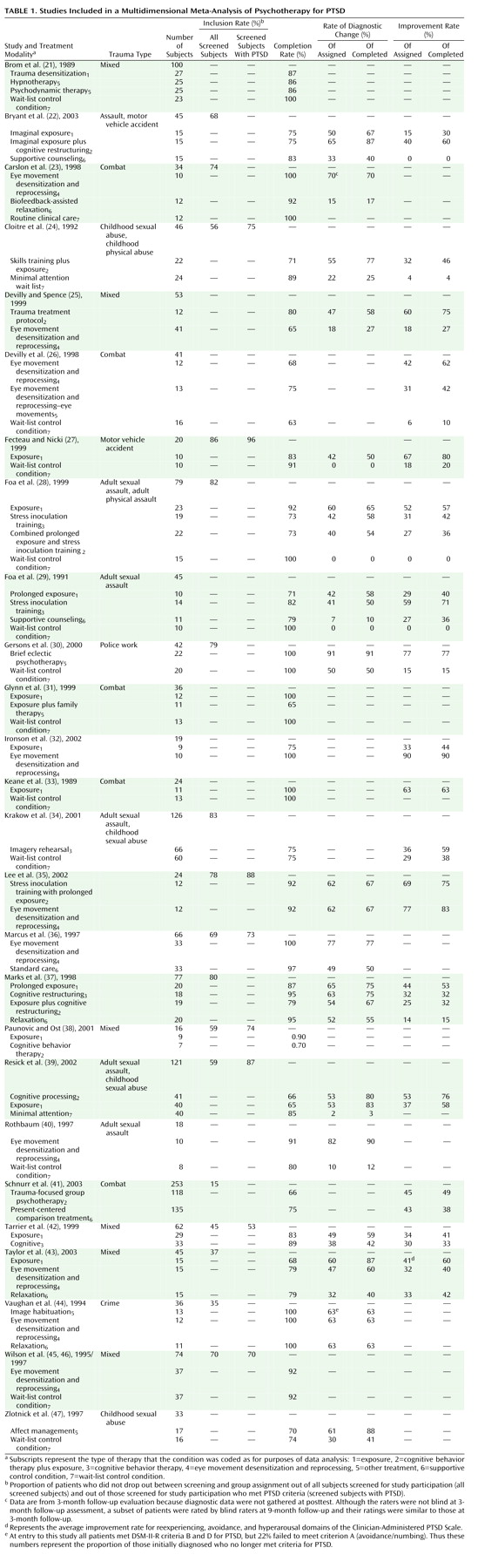

Table 1 lists each study, each active and control condition, and the data we extracted and analyzed so that researchers can directly assess our decisions and results. Decisions about how to code or define variables reflected our consistent efforts to 1) make methodological decisions prior to examining the data where possible, and 2) give the treatments under consideration the “benefit of the doubt”

(18). For example, when researchers reported alternative values for the same analyses in the text and tables, we used the values that had the best results for the treatment. Two raters (each blind to the other’s ratings) coded each of the variables to ensure accuracy.

Definition of Primary Variables

Number of participants refers to the number of people who actually began treatment (i.e., the number randomly assigned to any treatment condition who attended at least one session).

Number screened refers to the number of patients researchers reported screening for inclusion in the study (e.g., in initial interviews). In some cases, researchers first prescreened participants via phone and then in person. In these cases, we used the number screened rather than prescreened to maximize comparability to data from studies that did not report prescreening numbers. This produced a conservative estimate of number screened and exclusion rate because it does not include those initially screened out after a prescreening call (or those prescreened by referral sources, who are often aware of the kinds of patients researchers do and do not want included in a treatment study).

Number of exclusion criteria refers to the number of separate criteria used to exclude patients from a study. We did not count presence of psychosis, organic impairment, involvement in the legal system, or failure to meet criteria for PTSD in this number, given that these are criteria that would likely lead a clinician in everyday practice to refer the patient or apply a different treatment. Since researchers enumerated multiple exclusion criteria related to alcohol or drugs (e.g., drug abuse or dependence), we counted this as one exclusionary criterion to maximize comparability across studies. Determining the exact nature of the screening criteria was sometimes difficult because these criteria often included many unstated assumptions. Many studies offered broad exclusion criteria such as “major mental illness,” whereas others presented more precise lists. Thus, simply counting the number of screening criteria might not provide an accurate picture. As in prior meta-analyses

(17,

18), we assigned highly generalized criteria (e.g., severe chronic preinjury mental health difficulties) a score equal to the highest number of specific exclusionary criteria in the sample plus one.

Inclusion rate refers to the proportion of patients who were randomly assigned after surviving inclusion and exclusion criteria and attrition before the first treatment session.

Effect size was calculated by using Cohen’s d with the following formula: ([mean

1–mean

2]/[SD

12+SD

22])/2. When means or standard deviations were not reported, where possible we calculated effect size from other data provided

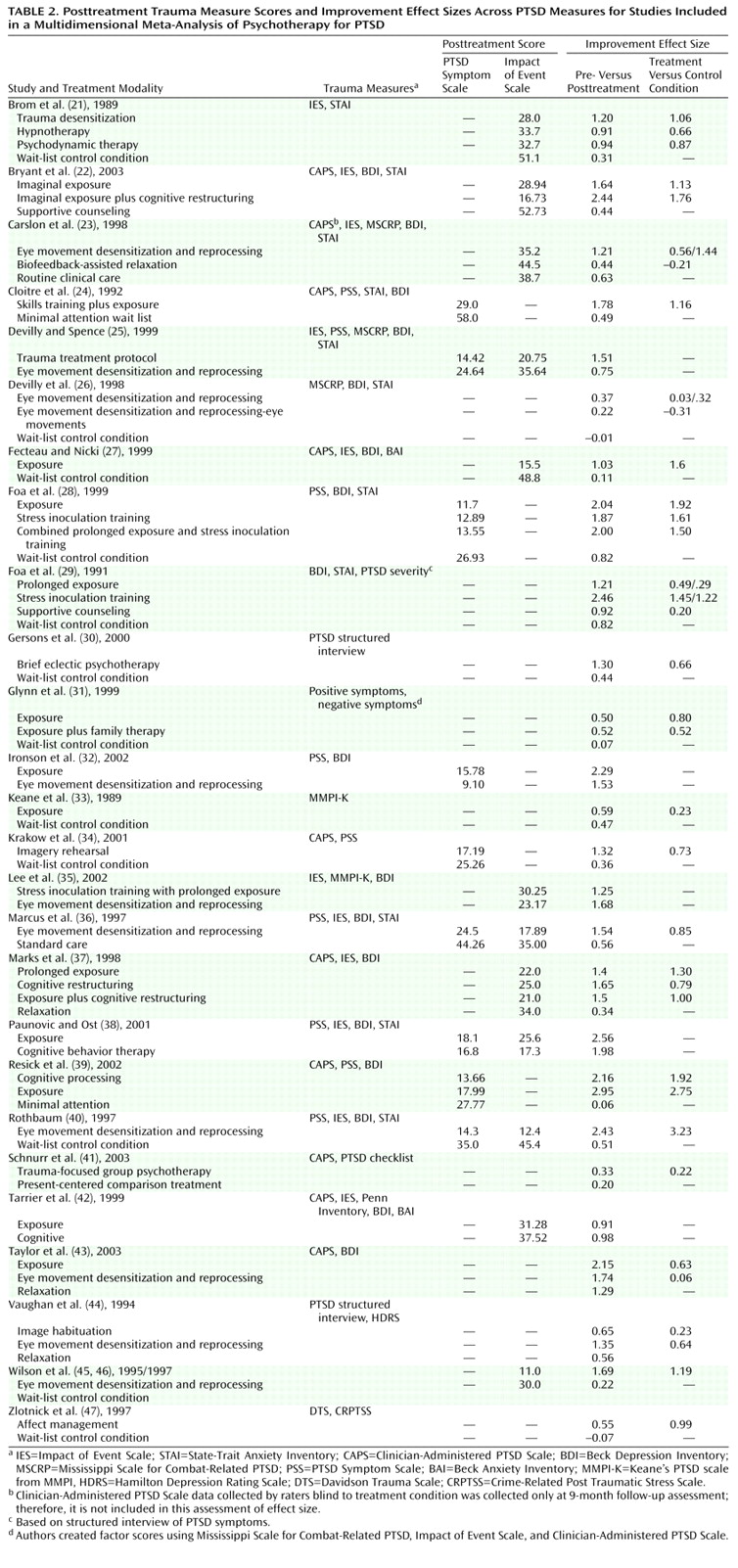

(20). For articles reporting effect sizes without reporting raw data, we relied on the effect sizes provided in the published report. Where data were provided only in graphic form, we interpolated. We calculated effect sizes for both pre- versus posttreatment and treatment versus control condition. In cases where both full-scale and subscale scores for a PTSD measure were reported, we used the full-scale score. If subscale data only were reported, we aggregated the scales. Where the investigators reported data on multiple measures of PTSD symptoms, we aggregated the effect sizes across measures. We present these effect sizes in

Table 2.

Posttreatment scores were analyzed by using the two most commonly used PTSD assessment instruments, the PTSD Symptom Scale (either the interview or self-report version) and the Impact of Event Scale.

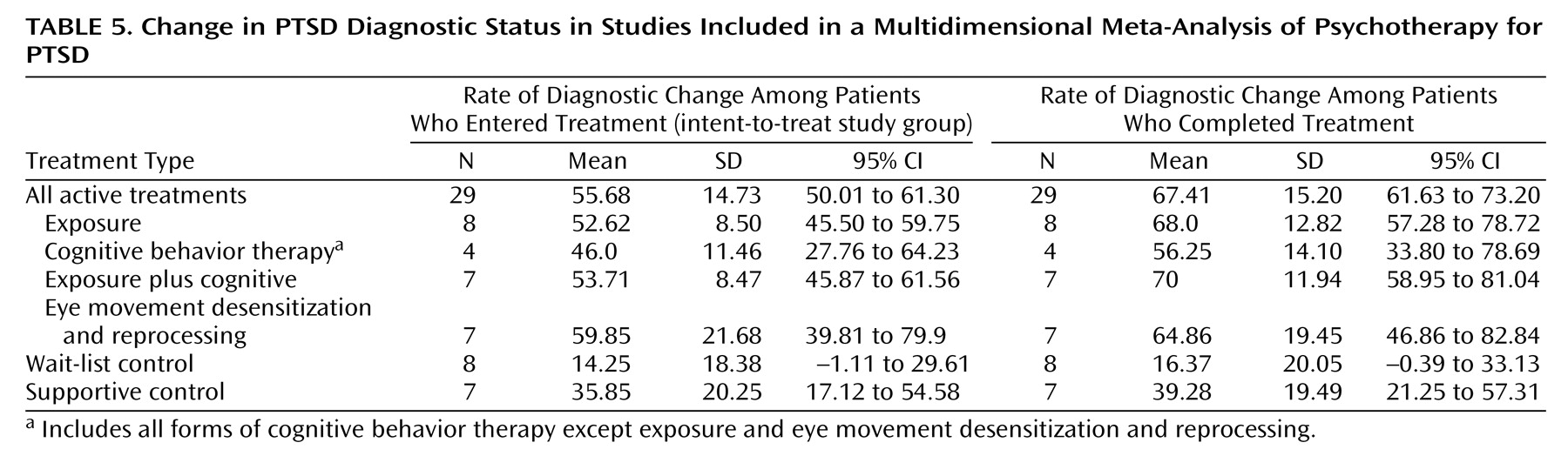

Rate of diagnostic change is the proportion of patients who met diagnostic criteria for PTSD pretreatment but no longer met these criteria posttreatment. We calculated this variable for both study completers and the intent-to-treat study group.

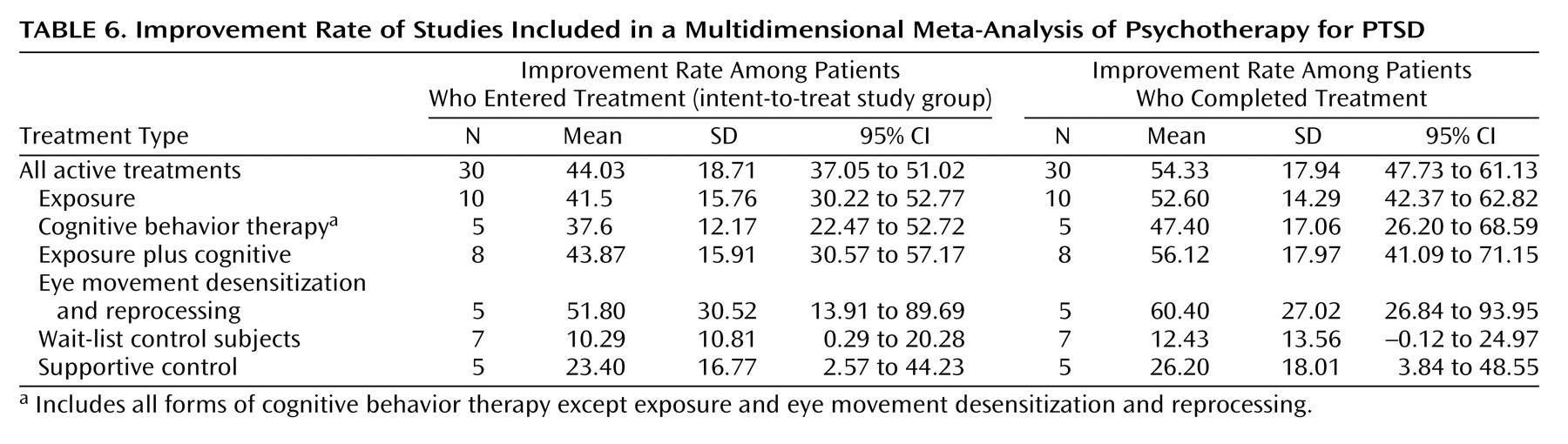

In the absence of agreed-upon standards for clinically meaningful improvement, as in prior studies, we calculated improvement rates (of patients entering as well as completing treatment) by relying on definitions for improvement used by the authors. Typical examples of criteria for improvement were PTSD Symptom Scale score <20 or a decrease of two or more standard deviations in PTSD Symptom Scale score.