Hair Apparent: Rapunzel Syndrome

Rapunzel had magnificent long hair, fine as spun gold.—The Grimm Brothers, Rapunzel (1)

Rapunzel’s hair fell to the ground like a rainbow. It was as strong as a dandelion and as strong as a dog leash.—Anne Sexton, Rapunzel (2)

History of the Problem

Emily (all names and identifiers have been changed to protect confidentiality) was a 7-year-old girl seen by her pediatrician for a routine annual examination. Although Emily had voiced no complaints, her mother had noted that she had appeared paler than usual. Upon physical examination, her pediatrician noted a nontender palpable mass in the child’s stomach, leading him to order an abdominal ultrasound. The study showed no evidence of any abnormalities, although the technician did note that Emily must have just eaten because her stomach was full. However, her mother reported that Emily had not eaten since breakfast, 4 hours earlier.On reevaluation the next day, Emily’s pediatrician still palpated the same mass, leading him to order a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen. The abdominal CT demonstrated a free-floating mass that filled the entire stomach and was surrounded by a thin rim of contrast material (Figure 1). Emily’s pediatrician did not think the mass was consistent with a neoplasm but was concerned that it could be a conglomeration of something she had ingested. Upon further questioning, Emily reported no stomach pain, nausea, vomiting, reflux, diarrhea, flatulence, recent illnesses, or fever. Her mother reported no change in her bowel habits and stated that Emily never wanted to eat much in one sitting.

Given the large size and appearance of the mass on tomography, a decision was made to remove it surgically. Just as the elective surgery was scheduled, Emily was referred for evaluation by the child psychiatry consultation-liaison team.

Initial Psychiatric Consultation

The child psychiatry team (A.S.F. and A.M.) met with Emily and her mother the morning before surgery. By her own and her mother’s account, she was happy and well adjusted. She had many friends and was enrolled in a mainstream public school second-grade class that she enjoyed.Emily lived in the home of a family friend with her mother (Kim), her older half sister, and her younger brother. Up until 2 years before, Emily had lived with her mother, siblings, and father in their own home. Kim felt that family life had been generally good during the marriage and that her husband had been a good father; Emily was especially close to him. Emily’s father, however, had a substance abuse problem that led to dissolution of the marriage 2 years before admission. After this, the parents’ relationship became strained, and Emily had not seen her father in a year.Emily was briefly in counseling to help her deal with the changes in her life surrounding her parents’ separation, but the counselor felt that she was coping well and did not require further psychotherapy. Kim, however, expressed private concern that Emily was not dealing with the loss of her father. Meanwhile, Emily had started at a new school and was doing well academically and socially.With this background information, further evaluation was deferred until after the surgery, when the identity of the mass would be elucidated.

Surgical Procedure

Because the mass in Emily’s stomach appeared too large to be removed laparoscopically, a gastrotomy was performed instead through a 7-cm median xiphoumbilical incision. The mass was found to be a trichobezoar, or hairball, 45 cm long and 8 cm in diameter (Figure 2). The hair mass was cast in the shape of the stomach, which it filled, and extended down through the distal end of the duodenum, past the ligament of Treitz.

Trichobezoars

Trichotillomania, Trichophagia, and Rapunzel Syndrome

Clinical Presentation

Developmental Features

Complications

A Parent’s Hair

The cutting of hair represents a restitution offered the mother, whom the subject fancies to have harmed in some fashion.—Jeffrey J. Anderson (33)

Further Psychiatric Consultation

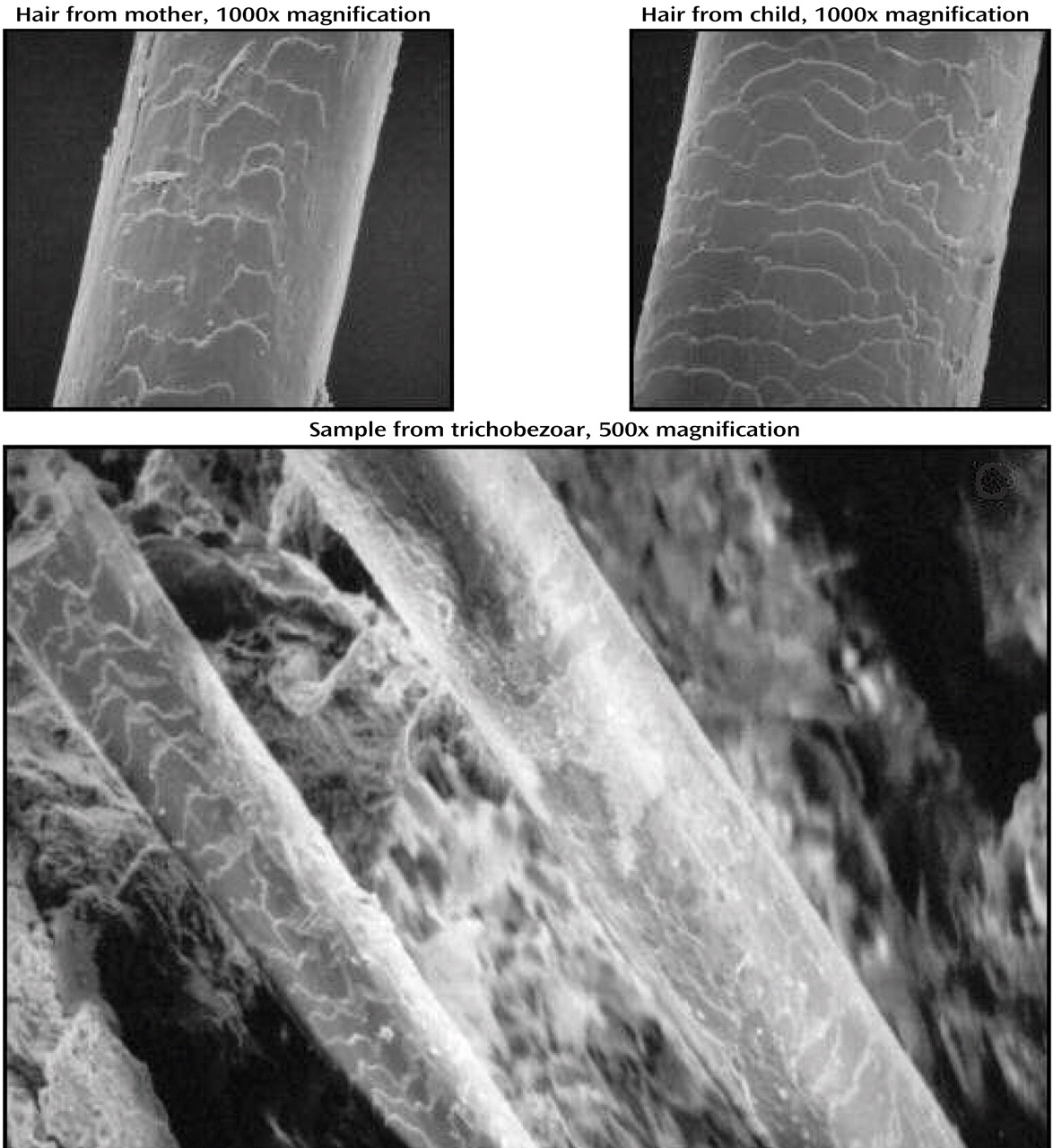

Upon discovering that Emily’s stomach mass was a trichobezoar, the psychiatric team reapproached her. Emily clearly had several nonspecific vulnerabilities putting her at risk for a psychiatric disorder: she had recently lost her father and had changed schools. Earlier, her father had been periodically absent and had a history of substance abuse. Furthermore, she had been witness to significant marital discord. However, these alone did not shed light on Emily’s trichophagia.Kim was completely taken aback by the finding in her daughter’s stomach, since she had never seen Emily eat or pull her own hair. She remembered that when Emily was 3, she had had the habit of chewing on her hair and her dolls’ hair, and this had concerned her. Her pediatrician, however, had not been concerned. Subsequently, Emily appeared to have stopped these behaviors. And yet, Emily’s hair had seemed to grow very slowly, and she had needed few haircuts during her 7 years. Emily, when interviewed alone, agreed that she used to chew her hair when she was “little.” Upon further questioning, she admitted that she had in the past sometimes twirled her hair around a finger and that hair would at times break off, and she would eat it. She denied a sense of tension or an urge before pulling or a sense of relief afterward. She said that she no longer pulled her hair but could remember doing it in the first grade. When asked why she had hair in her stomach, Emily was unable to explain how the hair had gotten there.Kim and Emily’s older sister both had very long hair, reaching past their waists. Although Kim assumed that she did shed hair around the house, she doubted that Emily was eating her hair and stated that she always kept her hairbrush in her purse, where Emily would not have access to it.Determining with certainty the provenance of the hair in the bezoar was a complicated process. The length of individual strands (over 25 inches for the longer ones) pointed to the mother’s and sister’s hair, as Emily’s own had never been over 12 inches long. The damage to the follicles and their cells did not permit DNA analysis that would have been confirmatory, and light microscopy did not help in differentiation. Scanning electron microscopy did offer useful information to distinguish between the daughter’s and mother’s hair. Specifically, the different widths and surface scaling patterns of the two allowed for ready differentiation of fresh hair clippings, as well as of hair samples taken from the bezoar itself (Figure 3). In summary, the combination of gross pathology and scanning electron microscopy techniques confirmed that hair in the bezoar had derived from at least two sources: Emily and her mother.

Psychiatric Formulation

Reclaiming Rapunzel

Rapunzel found the means of escaping her predicament with her own body.—Bruno Bettelheim (36, p. 17)

But what more reliable source to recovery do we have than our own body?—Bruno Bettelheim (36, p. 149)

Treatment Alternatives

Clinical Follow-Up and Prognosis

Emily was referred for outpatient psychiatric services after her discharge from the hospital and uneventful recovery from abdominal surgery. Seen at 1 and 2 months after discharge, she quickly thrived. She returned and readapted rapidly to school and family life. She appeared happy and carefree, reported no symptoms of depression or anxiety, and continued to deny pulling or eating of hair—her own or anyone else’s. Despite the watchful vigilance of her mother, sister, and grandparents, she was not found to engage in hair pulling or hair eating, and no areas of hair thinning or loss became evident. There was no evidence that trichotillomania, trichophagia, or pica had recurred.In light of these facts, specific treatment as outlined was not instituted at a specialty clinic, as had originally been considered necessary. Rather, Emily was referred for supportive individual and family counseling at a more conveniently located clinic and for periodic monitoring through the surgery and specialized child psychiatric services. Given that her hair-eating behavior may have continued undetected or eventually recurred, minimally invasive follow-up tests were to be performed biannually to ensure that no hair reaccumulation took place. These included abdominal ultrasound or simple abdominal X-rays after swallowing barium. Endoscopy or CT would be avoided unless absolutely necessary, given their intrusive nature and higher radiation dose, respectively.

Footnote

References

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Authors

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBGet Access

Login options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).