Neuroticism is a dimensional measure of an individual’s tendency to experience negative emotions that are manifested at one extreme as anxiety, depression, and moodiness and at the other as emotional stability. The heritability of neuroticism is well established

(1), and some studies have suggested that there is a substantial overlap between the genetic risk factors for neuroticism and major depression

(2). However, it is not known which biological correlates of neuroticism might give rise to the increased risk of clinical depression.

Major depression is often accompanied by hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis dysfunction

(3). Studies have suggested that the increase in salivary cortisol that follows waking provides a reliable dynamic measure of adrenocortical activity

(4) and that this response is increased in euthymic unmedicated patients with a history of depression

(5). However, it is unknown whether elevated waking cortisol is a risk factor for depression or a result of having been depressed or treated for depression in the past. The aim of this study was to examine waking cortisol in people with high or low levels of neuroticism without a history of mood disorder to test the hypothesis that high neuroticism itself is associated with altered adrenocortical regulation.

Method

Thirty healthy volunteers (ages 21–57 years) were selected by their neuroticism score on the Eysenck Personality Inventory. Individuals were chosen from a cohort of 20,427 families collected as part of an investigation into the genetic basis of personality

(6). We contacted unrelated individuals from selected extremes: 15 subjects (seven men, age: mean=39.5, SD=14.6) with extremely high scores for neuroticism (mean=21.3, SD=1.3, range=19–23) and 15 subjects (seven men, age: mean=46.9, SD=9.0) with extremely low scores (mean=0.53, SD=1.13) were included in the analysis.

On the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, subjects were determined to be free of past or current history of axis I disorder. They had no current physical illness and had been free of medication for at least 1 month. The group with high neuroticism scores had a mean score on the Beck Depression Inventory of 9.14 (SD=4.73), and the group with low neuroticism scores had a mean score of 3.07 (SD=2.34). The study was approved by the local ethics committee. All subjects gave written informed consent.

Fasting saliva samples were collected in salivette tubes with the first sample taken immediately upon waking and continuing at 15-minute intervals for the next hour

(7). After this, the subjects resumed normal activity. Subsequently, saliva samples were taken at noon, 6:00 p.m., and 10:00 p.m., with subjects avoiding food for 1 hour previously. The premenstrual week was avoided for women. Salivary cortisol was measured with an in-house double-antibody radioimmunoassay.

Salivary levels were analyzed with a two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), with group and gender asbetween-subject factors and time (sampling time) as the main within-subject factor and Huynh-Feldt correction (uncorrected dfs reported). Significant interactions were analyzed with post hoc t tests. The area under the curve for the first 60 minutes after waking was measured with the trapezoid method, with subtraction of baseline cortisol secretion.

Results

There was no difference in age between the groups (t=–1.67, df=28, p=0.10). The mean time of awakening did not differ between subjects with high neuroticism scores (7:03 a.m. ±41 minutes) and the subjects with low neuroticism scores (6:43 a.m. ±49 minutes) (t=1.15, df=28, p=0.26).

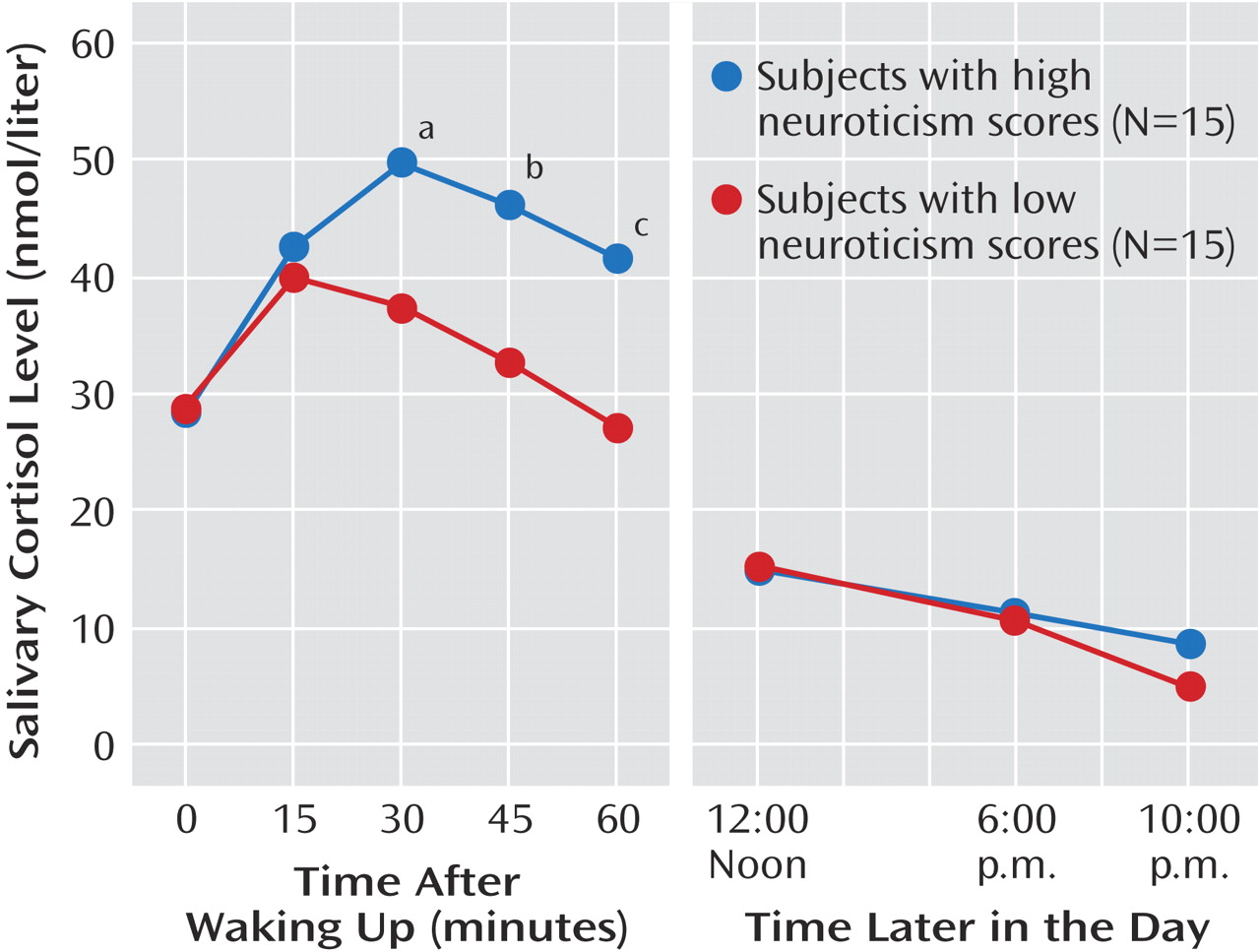

The ANOVA showed a significant group-by-time interaction (F=4.18, df=4, 104, p=0.005). Post hoc testing (

Figure 1) showed a greater increase in salivary cortisol 30 minutes after waking in the group with high neuroticism scores, and this difference from subjects with low neuroticism scores was maintained for the next 30 minutes. After that, levels of cortisol were similar for both groups. There was no effect of gender (F=2.47, df=1, 26, p=0.13) or gender by time (F=0.88, df=4, 104, p=0.48).

The area under the curve for cortisol secretion was substantially greater in the group with high neuroticism scores (mean=14.92 nmolhour/liter, SD=11.38, versus mean=5.79 nmolhour/liter, SD=9.46) (t=2.39, df=28, p=0.02). In the subjects with high neuroticism scores, there was a correlation between the area under the curve and neuroticism score (r=0.53, p=0.04); however, Beck Depression Inventory score did not correlate with cortisol area under the curve in the volunteers with high neuroticism scores (r=0.26, p=0.37).

Discussion

The subjects with high neuroticism scores showed significantly greater levels of salivary cortisol between 30 and 60 minutes after waking. It is well established that waking in the morning is followed by an adrenocortical response with brief ACTH and cortisol pulses in the majority of the subjects. The greater waking increase in free cortisol found in this study is similar to that reported in recovered depressed patients

(5). Also, we have recently identified a similar abnormality in unmedicated patients with acute major depression (Bhagwagar et al., unpublished). The salivary cortisol response to waking represents only a single aspect of HPA axis function; thus, we cannot conclude that neuroticism is associated with generally increased HPA axis activity. However, our observations are consistent with a greater ACTH response to waking or increased sensitivity of the adrenal gland to ACTH stimulation in subjects with high neuroticism scores.

Our group had no past or current history of depression, suggesting that increased waking cortisol is a risk factor for, rather than a consequence of, depression. It is possible that this abnormal response is inherited as part of the trait of neuroticism and, like high neuroticism scores, waking salivary cortisol levels show significant heritability

(8). Another possibility, however, is that the elevated waking cortisol levels might be a consequence of experiencing more subjective stress. Nonetheless, our data suggest that elevated morning cortisol levels can exist in the absence of major depression. In this respect, our findings could resemble the abnormal HPA axis activity seen in the first-degree relatives of depressed patients who have not experienced depression

(9). Longitudinal prospective studies initiated before the onset of depression are needed to untangle the relationship between neuroticism, cortisol hypersecretion, and depression.