Although it is unrealistic to expect a diagnostic classification to meet all the demands that may be placed on it, many clinicians believe that the current terminology and classification system performs poorly in respect to almost all of the functions of diagnosis just listed.

Shortcomings of the Somatoform Category

1. The terminology is unacceptable to patients

With increasing transparency in health care, the acceptability of diagnostic terms to patients is important. Although proposed as an atheoretical term, “somatoform” is commonly seen as related to the older term “somatization”

(12). This implies that the symptoms are a “mental disorder” in somatic form and may be regarded by patients as conveying doubt about the reality and genuineness of their suffering

(13).

2. The category is inherently dualistic

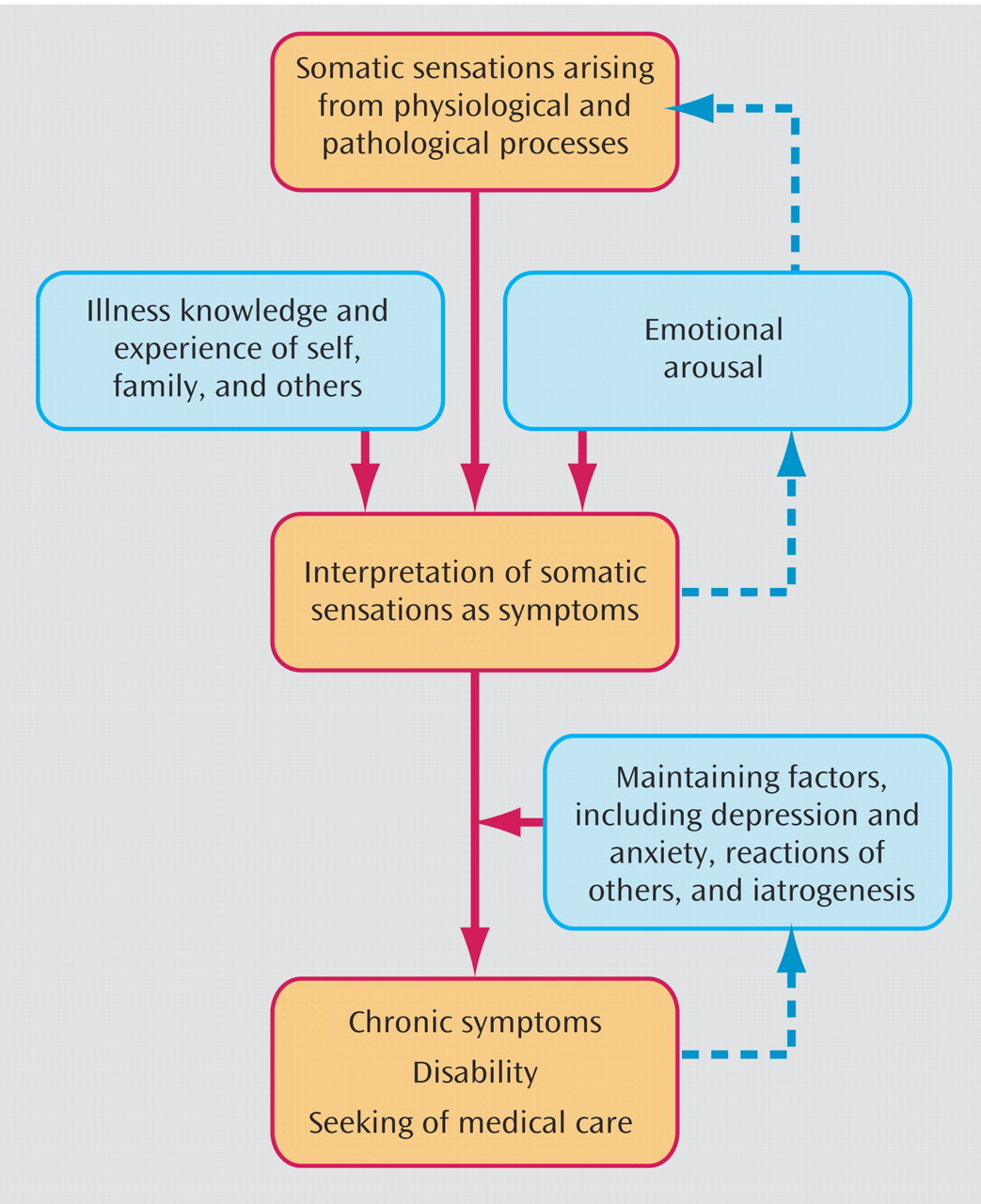

The idea that somatic symptoms can be divided into those that reflect disease and those that are psychogenic is theoretically questionable

(6). Indeed, the view that symptoms can be “explained” solely by a disease is a debatable one that is not entirely in accordance with empirical data

(14). In practice, most physicians adopt a broad perspective when assessing a patient’s symptoms

(15).

3. Somatoform disorders do not form a coherent category

The only common feature of somatoform disorders is that they show somatic symptoms without an associated general medical condition. Beyond that, they lack coherence

(9). The overlap with the many other psychiatric disorders that are also defined in part by somatic symptoms, such as depression and anxiety, is also a potential cause of misdiagnosis.

4. Somatoform disorders are incompatible with other cultures

Somatoform disorder diagnoses do not translate well into cultures that have a less dualistic view of mind and body (for example, the current Chinese classification is based on DSM but specifically excludes the somatoform disorder category

[16]). Exporting a dualistic diagnosis of somatoform disorder to these cultures at the same time that Western medicine is trying to escape it would seem to be counterproductive.

5. There is ambiguity in the stated exclusion criteria

The diagnosis of somatoform disorder requires the exclusion of general medical conditions. However, there is lack of clarity about which medical diagnoses should be regarded as exclusionary: for example, do medical “functional syndromes,” such as irritable bowel syndrome, count as exclusions? One consequence of this lack of clarity is that patients may be classified as having both an axis III disorder (for example, irritable bowel syndrome) and an axis I somatoform disorder (such as undifferentiated somatoform disorder or pain disorder) for the very same somatic symptoms. This seems to be ridiculous.

6. The subcategories are unreliable

Many of the subcategories of somatoform disorders have failed to achieve established standards of reliability

(17).

7. Somatoform disorders lack clearly defined thresholds

The lack of any clearly defined threshold for what merits a somatoform disorder diagnosis has led both to disagreement about the scope of this category and also to its gradual enlargement

(18). It is probably for this reason that most major epidemiological surveys of psychiatric disorders have excluded somatoform disorders.

8. Somatoform disorders cause confusion in disputes over medical-legal and insurance entitlements

Somatoform disorder diagnoses have proved problematic in relation to medical-legal and social security entitlements. On one hand, they can provide spurious diagnostic validation for simple symptom complaints, and on the other, they can undermine the reality of somatic symptoms as “merely psychiatric.” They thereby provide considerable scope for generating irresolvable differences of opinion.

In summary, the existing category of somatoform disorders may be regarded to have failed.

Shortcomings of the Specific Somatoform Subcategories

Somatization disorder is arguably the archetypical diagnosis of the somatoform disorder category. Its introduction was influenced by the then-recent work of the St. Louis group

(8). Arguably, it has subsequently received attention out of proportion to its prevalence relative to that of the other somatoform disorders. Furthermore, doubts have been expressed about both its clinical value and conceptual basis

(19). First, patients with somatization disorder have prominent psychological as well as somatic symptoms so that the syndrome is hardly an exemplar of a predominately somatic condition

(20). Second, it has a substantial overlap with personality disorders, particularly borderline personality disorder

(21). Third, although the requirements for diagnosis are unusual in that they rely on a lifetime history of symptoms, there is evidence that patients’ recall of past symptoms is variable and that the diagnosis has low stability in longitudinal surveys

(22). Fourth, it is based merely on counting the number of “unexplained” somatic symptoms and so lacks even face validity as a psychiatric disorder. The number of somatic symptoms a person reports is continuously distributed in the general population, and the diagnosis merely represents an extreme of severity on what appears to be a continuum of distress

(23). Finally, the diagnosis of somatization disorder offers the practitioner little specific guidance about treatment beyond clinical management aimed at minimizing health care use and iatrogenic illness

(24).

In response to the observation that many patients with chronic multiple symptoms do not meet the DSM-IV criteria for somatization disorder, attempts have been made to reduce the number of symptoms required for a diagnosis

(25,

26). Although these proposals have the advantage of acknowledging that the number of somatic symptoms forms a continuum, they retain the limitations of a diagnosis based almost exclusively on simply counting somatic symptoms.

Hypochondriasis as a diagnostic category remains controversial. Although there is good evidence of the cooccurrence of the triad of disease conviction, associated distress, and medical help-seeking, these symptoms are arguably better conceived of as a form of anxiety that happens to focus on health matters and is closely related to other forms of anxiety disorder

(27,

28).

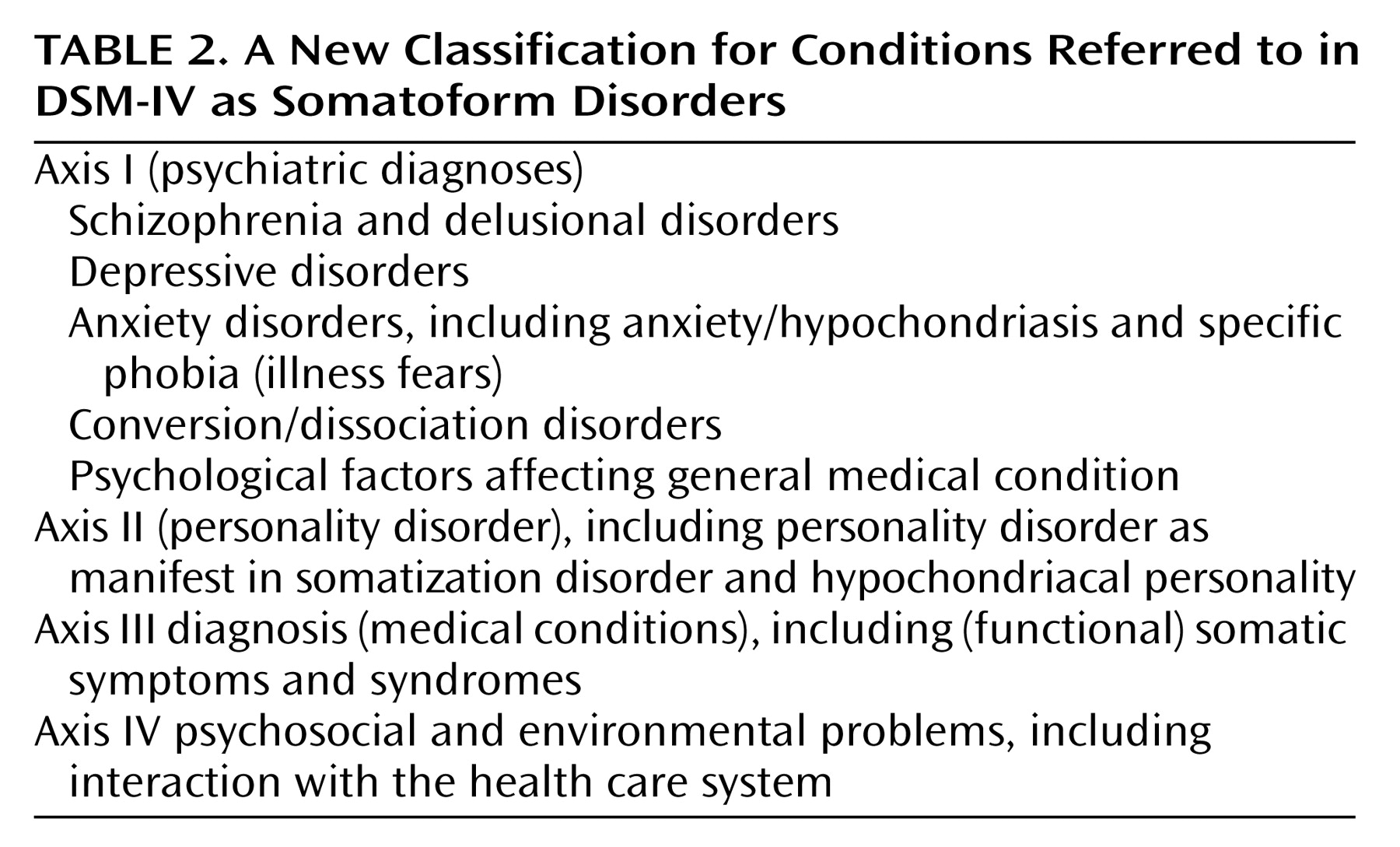

Conversion disorder has long been a problem for diagnostic classification. DSM-III placed it with other diagnoses in the somatoform section because of the shared characteristic of somatic symptoms that are not intentionally produced

(7). The DSM-IV workgroup recognized a close relationship with dissociative disorders but confirmed the DSM-III classification

(29). We propose that this discussion should be revisited.

Body dysmorphic disorder remains uncomfortably placed in the somatoform disorder category. There have been persuasive arguments that it should be rehoused; in particular, the suggestions that it might be better grouped with obsessive-compulsive disorder

(30) could be usefully revisited.

Undifferentiated somatoform disorder was placed alongside somatoform disorder not otherwise specified (the successor to atypical somatoform disorder) in DSM-III-R as a poorly defined catchall for the patients who did not fit into the original specific DSM-III categories

(31). However, it soon became clear that these were not merely small residual diagnoses but rather the most widely applicable categories. Even though this diagnosis is not widely used in clinical practice, its existence represents the need to have a diagnosis for a very large group of patients not easily classified elsewhere.

Pain disorder has undergone significant revision between DSM-III and DSM-IV. However, as noted by the Working Group for DSM-IV, there remain problems both in its definition and in establishing it as a separate disorder

(32).

In summary, many of the diagnostic subcategories currently housed within the somatoform disorders either lack validity as separate conditions or could be better housed elsewhere.