Past research among American Indians has revealed high rates of mental disorders, especially alcohol abuse/dependence and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

(1–

6). Substantial tribal differences in the prevalence of certain problems—notably alcohol and drug use

(7,

8)—underscore the importance of anticipating and accounting for social and cultural diversity in relation to such problems. Previous studies among American Indians, however, have used diagnostic measures and sampling methods that preclude comparison across tribes and comparison with national estimates. It is not surprising, therefore, that the Surgeon General’s report,

Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity (9), concluded that we lack even the most basic information about the relative mental health burdens borne by American Indians.

The American Indian Service Utilization, Psychiatric Epidemiology, Risk and Protective Factors Project (AI-SUPERPFP) was designed to allow direct comparisons between the baseline National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) sample and two American Indian tribes. The NCS, which assessed DSM-III-R diagnoses, has guided the national agenda regarding mental health planning over the last decade and thus provides an important point of reference for epidemiological studies of this nature. Here, we report the lifetime and 12-month prevalences of selected DSM-III-R disorders for two well-defined American Indian populations within the context of the NCS and examine differential risk for disorder by tribe, with adjustment for demographic correlates. We also examine patterns of help-seeking for symptoms of mental disorders.

Previous findings

(1,

2,

4–6) led us to hypothesize that rates of alcohol use disorder would be higher in these tribes, compared to the U.S. population as reflected in NCS. Our own studies among American Indian adolescents

(8) suggested that we also would observe significant tribal differences, namely a higher prevalence of alcohol use disorder in the Northern Plains than in the Southwest. There was good reason as well to suspect that the prevalences of major depression and PTSD in both tribes would exceed those found by the NCS for the general U.S. population

(3,

5). The paucity of relevant literature, however, rendered help-seeking among American Indians much more enigmatic, although we were confident that traditional healing resources would assume a prominent role in this process

(10,

11). The results of this inquiry represent an important step toward addressing the Surgeon General’s mandate to better describe the mental health disparities that plague American Indian communities.

Method

Sample

The AI-SUPERPFP populations of inference were 15–54-year-old enrolled members of two closely related Northern Plains tribes and a Southwest tribe living on or within 20 miles of their respective reservations at the time of sampling (1997). To protect the confidentiality of the participating communities

(12), we refer to them by these general descriptors rather than specific tribal names.

Tribal rolls formed the sampling universe; these records list all individuals meeting the legal requirements for recognition as tribal members. Stratified random sampling procedures were used with strata defined by cultural group, gender, and age (15–24, 25–34, 35–44, and 45–54 years). Records were selected randomly for inclusion into replicates, which were then released as needed to reach our goal of approximately 1,500 interviews per tribe.

As described in greater detail elsewhere

(13), an elaborate location procedure was developed that involved searches of public records and queries of family members and knowledgeable community “key informants”; supervisors rather than interviewers made the final location determination. In the Southwest and Northern Plains, respectively, 46.6% and 39.2% of those listed in the tribal rolls were found to be living on or near the reservations. Of those located and found eligible, 73.7% in the Southwest (N=1,446) and 76.8% in the Northern Plains (N=1,638) agreed to participate, with lower response rates for male tribal members and younger tribal members. In all analyses presented here, sample weights were used to account for differential selection probabilities across all strata and for patterns of nonresponse.

Data Collection

Tribal approvals were obtained before project initiation. Informed consent was obtained from all adult respondents; for minors, parental/guardian consent was obtained before requesting the adolescent’s assent. Ci3 Version 2

(14) was used to develop a computer-assisted personal interview that greatly facilitated administration of the complex diagnostic protocol. Tribal members who had received intensive training in research and interviewing methods read questions to the participants from a laptop computer screen and entered interviewees’ responses. For two sections of the interview—assessment of past criminal behaviors and HIV knowledge and behaviors (in the Northern Plains group only)—participants entered their responses directly into the computer.

Measures

The AI-SUPERPFP interview not only assessed mental disorder and help-seeking but also included measures of physical health, health-related quality of life, stress, and important psychosocial constructs (such as social support and coping). Both the protocol and the training manual are available on our web site (http://www.uchsc.edu/ai/ncaianmhr/research/superpfp.htm).

Diagnoses

Lifetime and 12-month mental health disorders were assessed, in English, by using the NCS’s University of Michigan Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) adapted for use in American Indian communities in the context of a previous study

(3). That adaptation included several modifications that were based on the results of focus group reviews by community members and service providers. For example, psychoses and mania were excluded because of concerns regarding the cultural validity of the measures. (For example, inquiries about hallucinations in cultures where the seeking of visions is nurtured must be more nuanced than would be possible in an interview conducted by lay interviewers.) Simple and social phobias and agoraphobia were deleted from consideration because of concerns about respondent burden. As a result, nine disorders were assessed in AI-SUPERPFP: major depressive episode, dysthymic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, PTSD, alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence, drug abuse, and drug dependence. Aggregations included any depressive disorder (major depressive episode or dysthymic disorder), any anxiety disorder (generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, or PTSD), any depressive/anxiety disorder, any substance use disorder (alcohol or drug abuse or dependence), and any AI-SUPERPFP disorder.

Help-Seeking

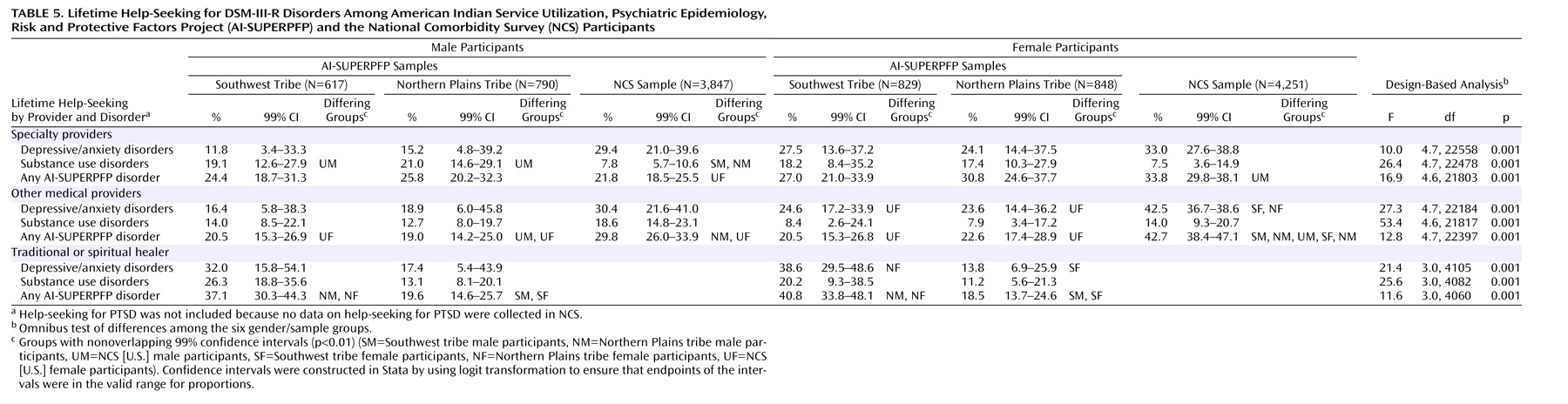

Questions about help-seeking were included in each diagnostic module and asked of all individuals who endorsed at least some symptoms of the disorder. These questions were patterned after the NCS questions but were adapted to reflect the service ecologies of American Indian reservation communities. Questions about traditional healers (including medicine men and spiritual and religious leaders) were included, in addition to questions about a wide range of specialty care providers (both mental health and substance abuse treatment providers) and other medical professionals. The present analyses focused on lifetime help-seeking for any depressive/anxiety disorder, any substance use disorder, and any AI-SUPERPFP disorder.

NCS Sample

Our comparison to the general U.S. population used the baseline NCS, described in detail elsewhere

(15). The NCS was conducted in a stratified, multistage area probability sample of 8,098 U.S. residents age 15–54 years in 1990–1992. As noted earlier, the help-seeking measures were located within the diagnostic modules. The NCS diagnoses reported here are restricted to those assessed in AI-SUPERPFP.

Analyses

Variable construction was completed with SPSS

(16) and SAS

(17); all inferential analyses were conducted with Stata’s “svy” procedures

(18) with sample and nonresponse weights

(19). Generally, the NCS diagnostic algorithms were used for the AI-SUPERPFP data. An exception was made for the diagnosis of major depressive episode. As reported in the companion article in this issue

(20), our initial analyses of data for depressive disorders demonstrated that the requirement for major depressive episode symptoms to co-occur within an episode and not to be due to a physical illness, medications, or substance use decreased the validity of the AI-SUPERPFP CIDI major depressive episode diagnosis, while dramatically decreasing prevalence. Thus, the major depressive episode diagnoses reported here did not include the co-occurrence or physiological/medical rule-out stipulations for the AI-SUPERPFP samples but did for the NCS sample; as such, the AI-SUPERPFP rates are higher than might otherwise be the case. NCS did not include help-seeking questions in its PTSD module; thus, for purposes of these comparisons, our results for help-seeking do not include data on help-seeking for PTSD for either the AI-SUPERPFP samples or the NCS sample.

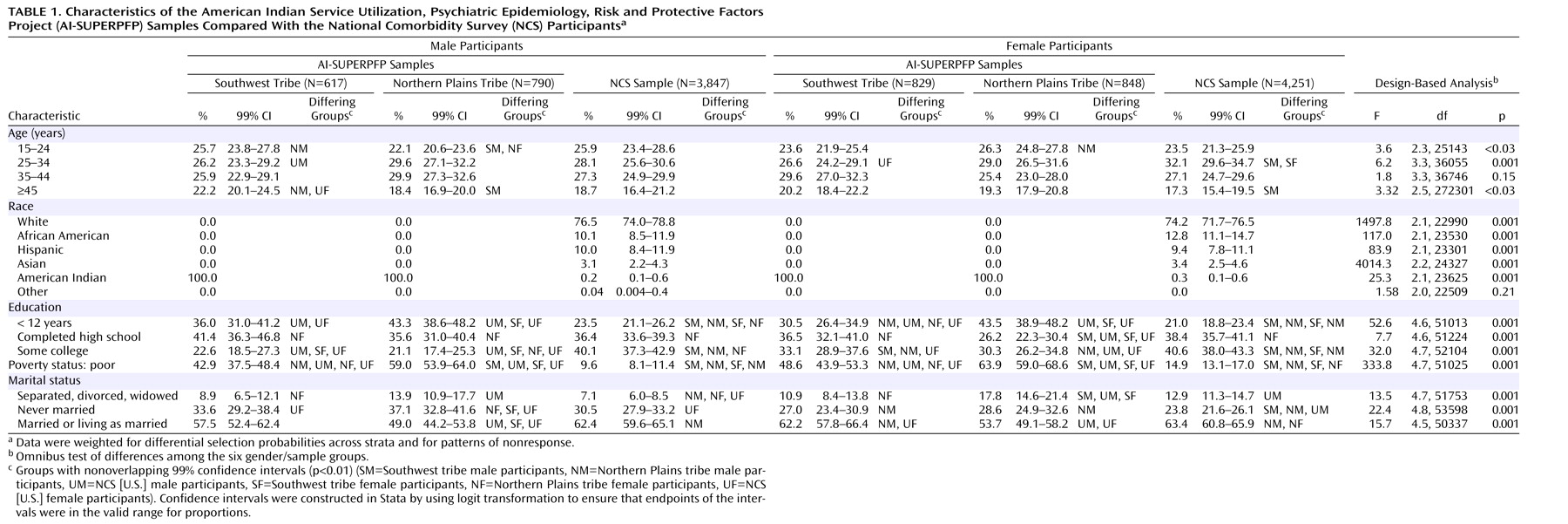

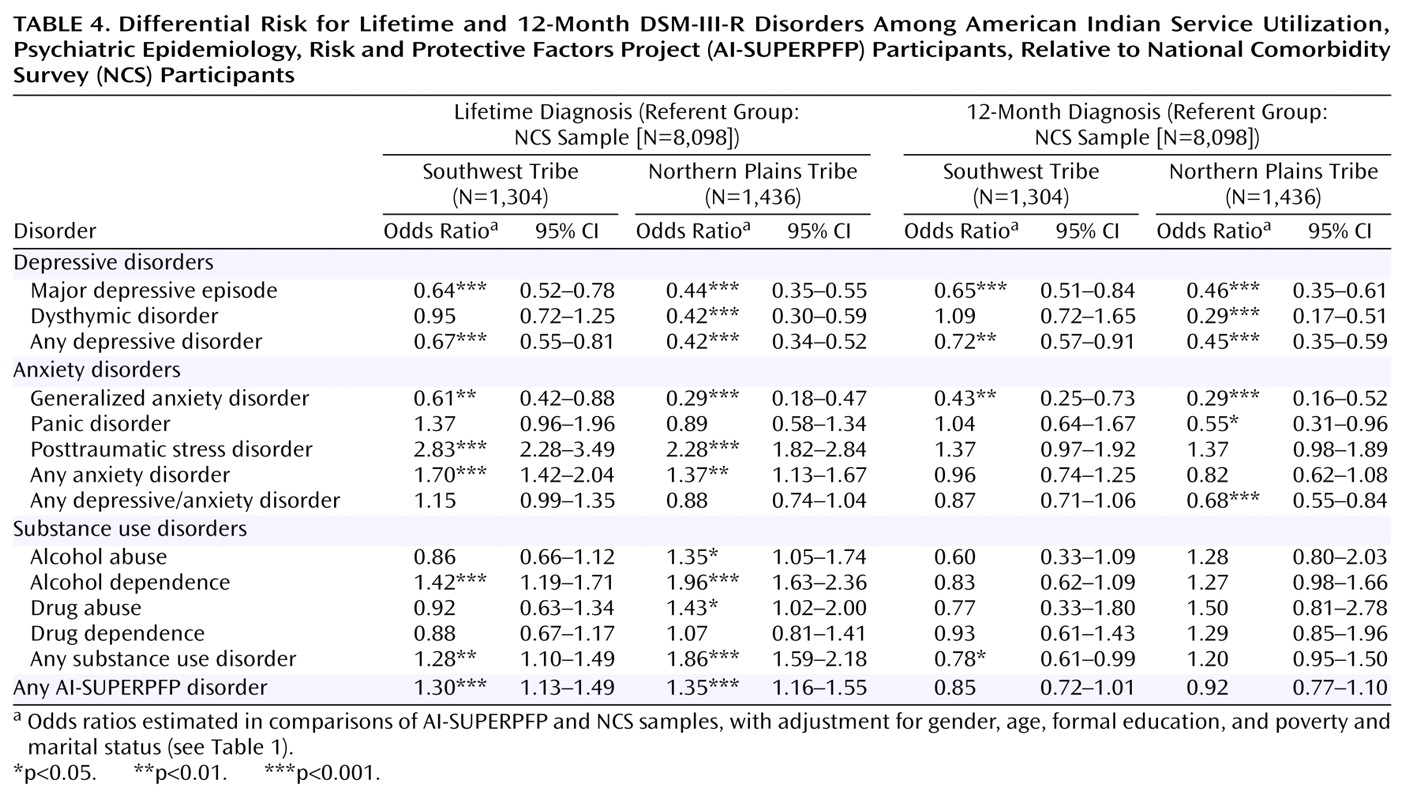

Prevalence estimates and 99% confidence intervals are reported for six groups: male and female members of the Southwest, Northern Plains, and NCS samples. Differences between specific groups were identified by means of nonoverlapping confidence intervals. A combined AI-SUPERPFP/NCS data set was analyzed with logistic regression methods to determine whether the tribal samples were at differential risk for disorder, after a common set of demographic variables was taken into consideration. Separate logistic regression analyses were calculated for each lifetime and 12-month diagnosis. To assess whether the tribes were at differential risk for each diagnosis, logistic regression analyses were conducted with dummy variables denoting tribal membership entered along with those denoting demographic factors (gender, age, formal educational attainment, poverty, and marital status). The primary hypothesis addressed was that tribal disparities would remain despite adjustment for possible demographic confounding factors. Only the odds ratios for each tribe are reported. (The results for the demographic correlates are available on request.) Because of the large size of these samples and the number of analyses, we adopted a conservative stance in interpreting regression coefficients, focusing only on those with p values less than 0.01.

Discussion

Limitations in the AI-SUPERPFP sample, study design, and instrumentation have been discussed at length elsewhere

(13). Briefly, the AI-SUPERPFP samples, while well defined and justified, were limited in cultural representation, age range, and residence. As with other studies of this type, AI-SUPERPFP relied on retrospective self-reports of psychiatric symptoms as reported to lay interviewers using highly structured protocols. Furthermore, joint analyses of data sets such as AI-SUPERPFP and NCS have methodological limitations. The data collection periods necessarily varied as did the methods—at least to a certain extent. The NCS data were collected in 1990–1992; the AI-SUPERPFP data, between 1997 and 1999. Further, by focusing on the disorders assessed in AI-SUPERPFP, this report differs from others that have used the NCS data, for example, by excluding phobic disorders, bipolar disorder, and nonaffective psychoses. The AI-SUPERPFP CIDI was carefully adapted to enhance cultural validity. In most cases, these adaptations consisted of adding questions while retaining the NCS wording wherever possible

(13). The rates reported here did not include most of these enhancements, and, with the exception of major depressive episode, all AI-SUPERPFP diagnoses were determined with the same algorithm that was used in NCS. Further analyses are needed to examine the cultural validity of the AI-SUPERPFP CIDI and, more generally, of DSM-defined disorders.

These limitations notwithstanding, this report describes (for the first time, to our knowledge) the prevalence of common psychiatric disorders and associated help-seeking in a comparative context. Comprehensive assessments of adults within American Indian communities have been rare, but existing research has shown high rates of disorder, especially disorder related to alcohol use and trauma

(1,

2,

4–6). As with AI-SUPERPFP, these studies found alcohol use disorders to be most common; however, the alcohol use disorder rates reported here are substantially lower than those reported in previous efforts that used different assessment methods and in which participants were not selected with stratified random sampling procedures. Tribal representation also varied. Thus, methodological differences likely account for these discrepancies.

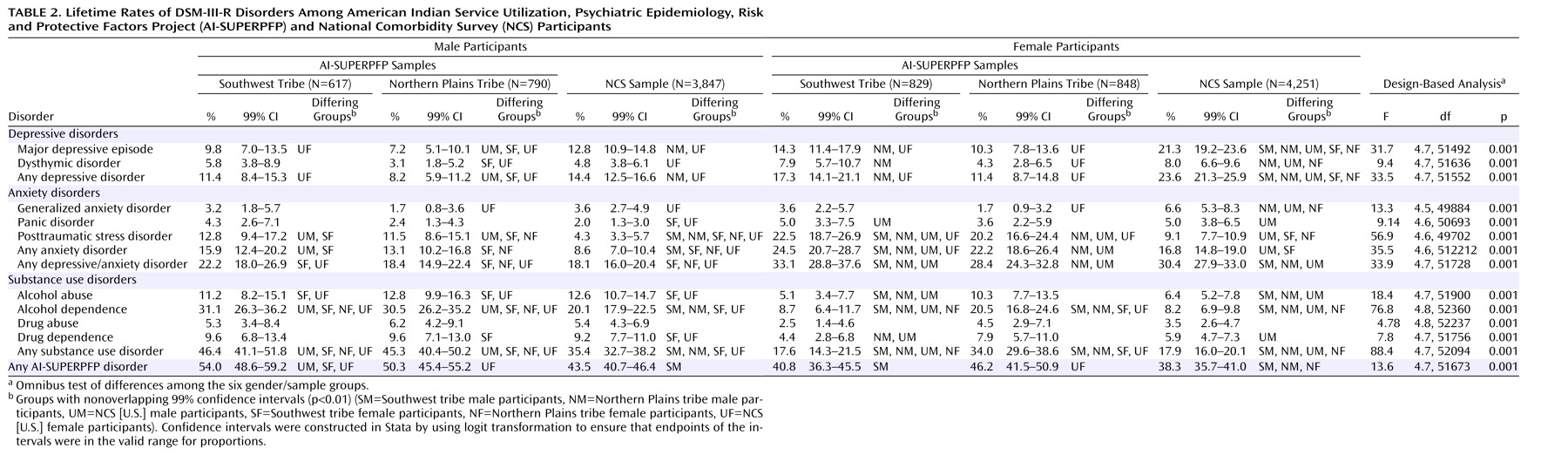

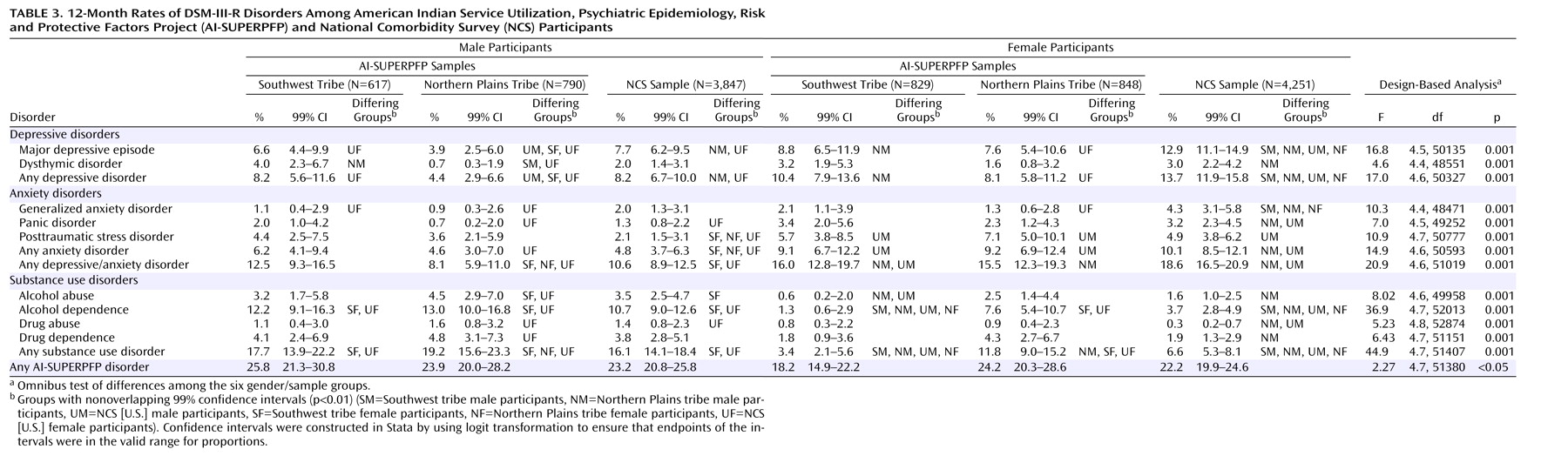

This work adds to the growing literature on mental health disparities among ethnic and racial populations in the United States. The distribution of DSM-defined disorders in these reservation-based tribal populations differed by both tribe and gender from that in the U.S. general population (as depicted by the NCS sample). Lifetime rates of any disorder were higher in Southwest men (but not Northern Plains men), compared to men in the NCS sample. Women in the Northern Plains tribe (but not in the Southwest tribe) were at higher risk than were the women in the NCS sample. Examination of data for individual disorders indicated that, among men, both the American Indian samples had higher rates of alcohol dependence and PTSD, compared to others in the United States, rendering these samples at higher risk for substance use disorders and anxiety disorders overall. Even with the more liberal operationalization of major depressive episode for AI-SUPERPFP (specifically, the exclusion of the requirement of at least three symptoms co-occurring during an episode and the stipulation that symptoms not be due to physiological effects or medical conditions), three of the four American Indian samples—Northern Plains men, Northern Plains women, and Southwest women—reported lower rates of major depressive episode, compared to the NCS sample. Although Northern Plains men were at higher risk for alcohol use disorders, their lower rate of major depressive episode rendered their overall prevalence rate for all disorders considered in AI-SUPERPFP comparable to that for U.S. men. Among women, both American Indian samples were at higher risk for PTSD, compared to women in the NCS sample. Northern Plains women were at lower risk for dysthymic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder but had a rate of alcohol dependence more than twice that of either U.S. or Southwest women and were, thus, at greater risk for any AI-SUPERPFP disorder.

These patterns emerge even more clearly once the demographic differences between samples were included in the models of estimation. In these multivariate analyses, both American Indian tribes were at higher risk for a lifetime DSM-III-R disorder but not for a 12-month disorder, compared to the NCS sample. Focusing on individual disorders, the tribes were at lower risk for both lifetime and 12-month major depressive episode and generalized anxiety disorder and at higher risk for lifetime, but not 12-month, PTSD and alcohol dependence.

Such findings are both similar to and different from reports regarding other ethnic and racial minorities in the United States. Rates of depressive disorders are often reported to be lower among African Americans, Hispanics, and Asian Americans, compared to whites

(9,

21). Similarly, PTSD is often associated with the struggles of living in impoverished communities, although, to our knowledge, most of this research has been limited to urban contexts

(22). American Indians in poor rural communities are also at heightened risk of trauma and resultant PTSD

(3,

23). Compared to whites, African Americans and Asian Americans tend to have lower rates of substance use disorders, and Hispanics often have generally comparable rates

(21). A study of Mexican Americans found that those born in the United States were at higher risk for alcohol dependence, compared to those born in Mexico

(24). Similarly, Southwest women, as the carriers of tradition in this matrilineal culture, may have greater ties than others in AI-SUPERPFP to their Native ways and thus be at less risk for the development of alcohol use disorders. Although such findings argue against stereotyped conclusions about the extent of alcohol problems in American Indian communities, clear disparities in risk for alcohol dependence existed for three of the four American Indian samples defined by tribe and gender.

The prevalence rates of the less common AI-SUPERPFP disorders—dysthymic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and panic disorder—provide additional information about mental health disparities. The pattern for dysthymic disorder generally reflected that for major depressive episode: Where differences occurred, the Northern Plains participants were less likely to meet the criteria for dysthymic disorder, compared with the other samples. Lifetime generalized anxiety disorder was less common among the Northern Plains women than among U.S. women. The rates of lifetime and 12-month panic disorder and 12-month generalized anxiety disorder were generally comparable in the AI-SUPERPFP and NCS samples.

Mental health services for American Indians are acknowledged to be scarce

(9,

25,

26). Our findings suggest that the rate of help-seeking for substance use disorders was relatively high in the American Indian samples. The exclusion of PTSD from the help-seeking analyses and the low prevalence of major depressive episode precluded a powerful test of relative help-seeking for depressive/anxiety disorders. Even so, American Indian women were less likely to seek help for depressive/anxiety disorders from nonspecialty providers. Not considered here is whether the help sought was considered efficacious and/or was of sufficient duration to be helpful

(9). The reliance on traditional resources—especially in the Southwest—is a consistent finding

(10) and underscores the need to better understand the importance of such healing in the service ecology of American Indians.