Rates of major depressive disorder rise dramatically in adolescence, with an estimated lifetime prevalence of 15% in adolescents by ages 15–18. Major depression is associated with significant morbidity, including deterioration in academic functioning, increased risk of substance use, and attempted and completed suicides

(1,

2) . Furthermore, adolescent major depression is a strong predictor of major depression in adulthood, which carries its own burden of disadvantage

(3) . These findings highlight the need for specific neurobiological research in adolescent major depression.

Converging lines of evidence suggest that the pathophysiology of depression entails impairment of cellular resilience and neuroplasticity in specific cortical, subcortical, and limbic brain regions. The relationship between the basal ganglia and depression has been inferred from the high comorbidity between depression and Parkinson’s disease as well as Huntington’s disease, both basal ganglia-related disorders. In addition, morphometric studies (but not all) and functional neuroimaging studies have documented smaller caudate, putamen, and thalamus as well as impaired metabolism and blood flow in the striatum and thalamus in depression

(4 –

10) .

Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (

1 H-MRS) has provided additional evidence for the involvement of the striatum in adult major depression.

1 H-MRS provides metabolic assay of neuronal cells, cell energetics, density, membrane turnover, gliosis, and glycolysis through their respective surrogate markers,

N -acetylaspartate, creatine, choline,

myo -inositol, and lactate levels

(11) .

1 H-MRS studies have corroborated the role of impaired cellular resilience in the basal ganglia of adults with major depression through abnormal levels of choline and

N -acetylaspartate. Charles et al.

(12) reported that elevated choline/creatine ratios decreased after antidepressant treatment, whereas a later study by Renshaw et al.

(13) yielded opposite results. Hamakawa et al.

(14) found higher choline levels and choline/creatine ratios in bipolar patients during a depressive episode. Vythilingam et al.

(15) reported lower caudate

N -acetylaspartate/creatine ratios and increased choline/creatine ratios in the putamen in major depression. The discrepant findings may be attributed in part to methodological issues, such as the use of single-voxel methods susceptible to partial volume effects given the small size and irregular shape of the striatum and thalamus; ratios to creatine, which increase variability

(16) ; use of a lower magnetic field (1.5-T) of lower sensitivity and spatial and spectral resolutions. They may also reflect differences in participant selection criteria, such as age range, depression severity, medication status, and family history.

To our knowledge, there have been no

1 H-MRS studies of the striatum in pediatric major depression. We believe that such research is important because establishing neuromarkers early in the course of the illness is likely to minimize confounding effects of chronicity and comorbidity and facilitate identification of at-risk individuals. We hypothesized that adolescents with major depression exhibit increased striatal choline and creatine and decreased

N -acetylaspartate compared with healthy comparison subjects but exhibit no differences in the thalamus. This hypothesis is based on models of major depression that entail impaired neuroplasticity and its collateral consequences of increased membrane turnover and impaired metabolism and neuronal viability

(17) .

Methods

Participants

Fourteen adolescents (eight of them female) 12–19 years old (mean age=16.2 years, SD=2.1) who had symptoms of major depressive disorder for at least 8 weeks and had a score ≥40 (mean=63.6, SD=15.4) on the Children’s Depression Rating Scale—Revised were enrolled from the New York University (NYU) Child Study Center, the Department of Psychiatry at Bellevue Hospital, and the inpatient psychiatric unit at NYU Tisch Hospital, all in New York City.

Ten healthy comparison subjects (six of them female), group matched for gender, age, and handedness, were recruited from families of NYU staff. For participants age 18 and over, written informed consent was obtained; those under age 18 provided assent and a parent or guardian provided signed consent.

A child psychiatrist interviewed participants about themselves and parents about their child with the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children—Present and Lifetime Version. Based on the interview, the psychiatrist rated each participant’s severity of depression on the Children’s Depression Rating Scale and on the severity item of the Clinical Global Impression. Participants also completed the Beck Depression Inventory, 2nd ed. Family medical and psychiatric history was obtained by reports from participants and parents.

Exclusion criteria for all participants were IQ below 80, significant medical or neurological disorder, and the usual MRI contraindications, including claustrophobia, ferrous implants, ink tattoos, metallic oral devices, large body habitus, or positive urine pregnancy test. Patients with major depressive disorder were excluded if they had a current or past DSM-IV diagnosis of bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, pervasive developmental disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, Tourette’s disorder, or eating disorder or if they had a substance-related disorder in the past 12 months. Comparison subjects were excluded if they had any major current or past DSM-IV diagnosis or a Children’s Depression Rating Scale score above 28.

MR Data Acquisition

All scans were done with a Trio 3-T full-body MRI scanner (Siemens AG, Erlangen, Germany) using a TEM3000

(18) transmit-receive head coil (MRI Instruments, Minneapolis). For image guidance of the MRS volume of interest, we used T

1 -weighted (echo time=4 msec, repetition time=1,130 msec) and axial T

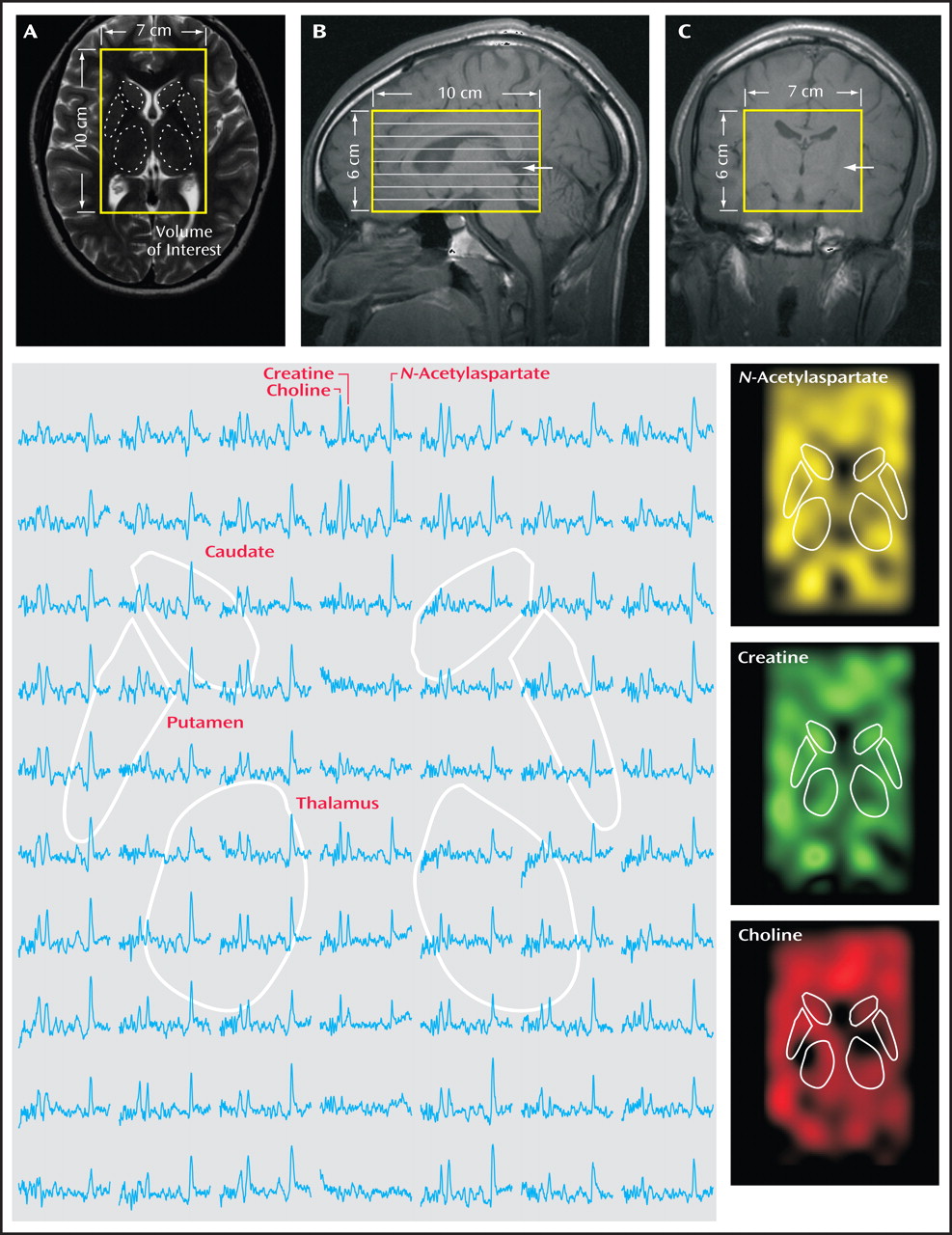

2 -weighted (echo time=80 msec, repetition time=2,500 msec) MRI, as shown in

Figure 1, panels A–C. For both contrasts, field of view=240×240 mm

2, matrix=512×512, and slice thickness=7.5 mm in the axial and 5 mm in the coronal and sagittal planes were used.

For

1 H-MRS, our automatic shim yielded 5.0 Hz (SD=1.0) linewidth for the metabolites in every voxel. A 10-cm (anterior-posterior) × 7-cm (left-right) × 6-cm (inferior-superior) volume of interest (420 cm

3 ) was image-guided onto the anatomic structures of interest, as shown in

Figure 1 . The volume of interest was excited using point-resolved spectroscopy (echo time=135 msec, repetition time=1,600 msec) and subdivided into eight inferior-superior axial slices with Hadamard spectroscopic imaging

(19) . These slices were partitioned with two-dimensional chemical-shift imaging into 16 (anterior-posterior) × 16 (left-right) voxels, each a nominal 0.75 cm

3 (19) . The MRS took 27 minutes and the entire protocol less than an hour. An example of an axial spectra matrix covering the caudate, putamen, and thalamus of an adolescent with major depressive disorder is shown in

Figure 1 .

MRS Data Processing

The MRS data were processed offline using in-house software. Residual water was removed from the free induction decays in the time domain. The data were then voxel-shifted to align the chemical-shift imaging grid with the

N -acetylaspartate volume of interest, zero-filled from 16×16×8 to 256×256×8, apodized with a 3-Hz Lorentzian, Fourier-transformed in the temporal, left-right, and anterior-posterior direction and Hadamard-reconstructed along the inferior-superior line. No spatial filters were applied. Spectra were automatically corrected for frequency and zero-order phase shifts in reference to the

N -acetylaspartate peak in each voxel

(19) .

Relative

N -acetylaspartate, creatine, and choline levels were estimated from their peak area using parametric spectral modeling

(20) . These relative levels were scaled into concentrations, [ Q], in each voxel using phantom replacement against a 3-liter sphere of 10.9 mM

N -acetylaspartate in water

(21) . The [ Q]’s were corrected for differences between the phantom in vitro

N -acetylaspartate levels (T

1 vitro / T

2 vitro =1.4/0.75 s) and those reported in vivo of

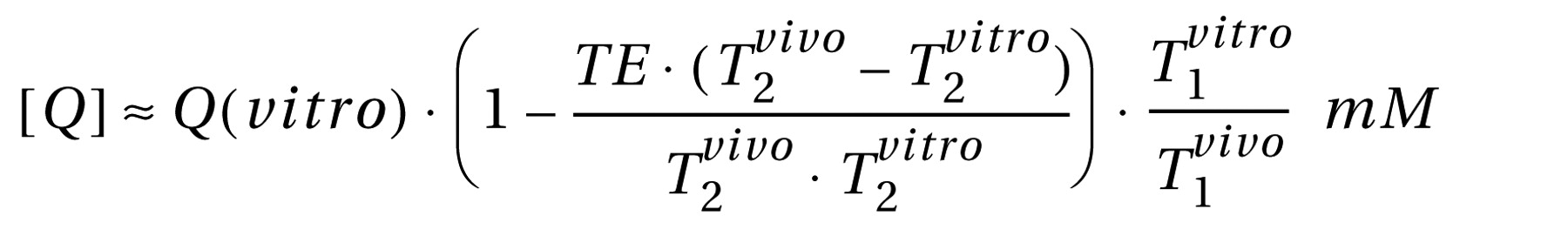

N -acetylaspartate (1.4/0.43 s), creatine (1.6/0.21 s) and choline (1.2/0.36 s), using the following formula

(22,

23) :

Although the assumption of a single T

1 and T

2 for each metabolite ignores possible regional variations

(22), it does not alter our analyses since we compare similar regions across subjects.

The thalamus and striatum were outlined manually on an axial T

2 -weighted image, as shown in

Figure 1, panel A. For each patient, only the one

1 H-MRS slice that best contained the bilateral striatum and thalamus was used. Our in-house software scaled and transcribed the outlined regions onto the quantitative metabolic maps and calculated for each one the volume (the sum of the circumscribed voxels), the sum of the [Q]’s from the equation above for each metabolite, and their standard deviations. Each metabolite’s concentration was obtained by dividing the sum of the [Q]’s by the appropriate volume. Note that after the 16×16 to 256×256 zero-filling, the in-plane MRS voxel resolution for the tracing (0.625 mm

2 ) was sufficient to avoid ventricular CSF and surrounding white matter. If the line delineating a structure passed anywhere inside any of these interpolated voxels, their volume and metabolic contents were added to the respective sums.

Statistical Analyses

Mixed-model regression was used to compare patients and comparison subjects with respect to the mean of each metabolite in each region (left and right caudate, putamen, and thalamus), while accounting for group differences in the volume of the given region. A separate analysis was conducted for each metabolite concentration within each region. In each case, the dependent variable consisted of the measures acquired on each side of the given region. Independent variables included subject group (index versus comparison subjects) and side (left versus right) as fixed classification factors, and the term representing the interaction between group and side (to determine whether group differences were the same on the left and right sides of the relevant brain region), and region volume as a numeric factor.

The variance-covariance structure was modeled by assuming observations to be correlated only when obtained from the same subject, and by allowing the error variance to differ across subject groups. All reported p values are two-sided type 3 significance levels from F values (df=1, 21), with statistical significance set at p<0.05.

Results

Participants

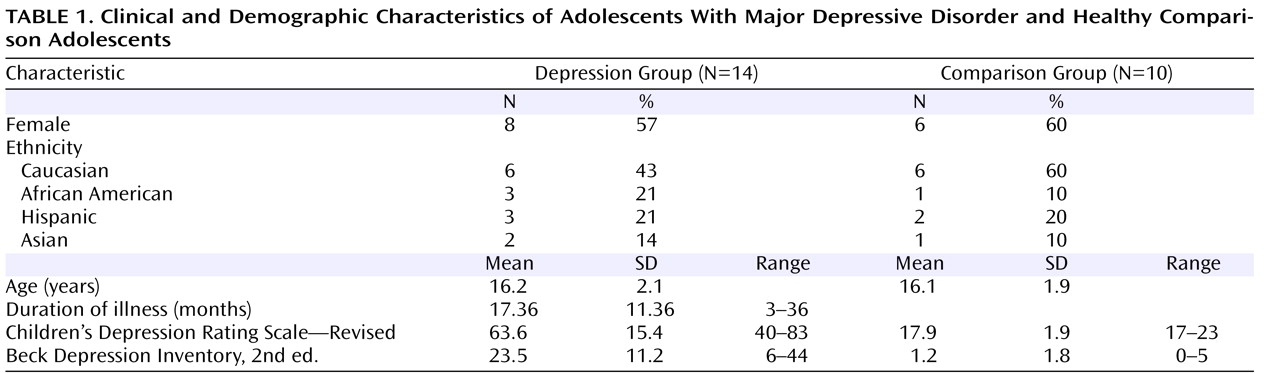

At the time of the scan, four patients were medication-naive, two had been psychotropic-free for at least 1 year, and eight had been treated with psychotropic medications for periods ranging from 2 months up to two and a half years. All patients on medication had not responded at the time of their scan. Medications included selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (four patients were taking fluoxetine, two were taking sertraline, one was taking escitalopram, and one was taking citalopram). Additionally, three were also taking lithium, one was taking lamotrigine, and one was taking risperidone. Two patients had social phobia and one had attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Seven patients had a parental history of major depression. None of the comparison subjects’ parents had any psychiatric disorders. Patient and comparison group characteristics are summarized in

Table 1 .

Volumetry

The mean volumes of circumscribed left and right regions of interest in the patient group were as follows: thalamus, 3,214 mm 3 (SD=305) and 3,232 mm 3 (SD=368); caudate, 811 mm 3 (SD=59) and 796 mm 3 (SD=49); and putamen, 885 mm 3 (SD=84) and 903 mm 3 (SD=84). In the comparison group, the mean volumes were as follows: thalamus, 3,251 mm 3 (SD=336) versus 3,241 mm 3 (SD=311); caudate, 821 mm 3 (SD=38) versus 796 mm 3 (SD=31); and putamen, 889 mm 3 (SD=77) versus 880 mm 3 (SD=74). Neither region showed any significant difference between the sides (left versus right) or between groups.

Note that these regions of interest included edge voxels even when they fell only partly within the circumscribed region. To estimate the edge voxels’ partial-volume contribution, we considered the surface-to-volume ratio for these structures. With a voxel volume of 2.9 mm 3 and thalamic region-of-interest volumes of ∼3,230 mm 3, ∼118 out of 1,103 voxels were at the surface, where their partial volume can be anywhere from 1% to 99%. Assuming an average partial volume of 50%, the partial volume would be ∼5.4% in the thalamus (118/110350%), ∼10.7% (30/27950%) in the caudate (average volume, 810 mm 3 ), and ∼10.2% (31/30750%) in the putamen (average volume, 890 mm 3 ).

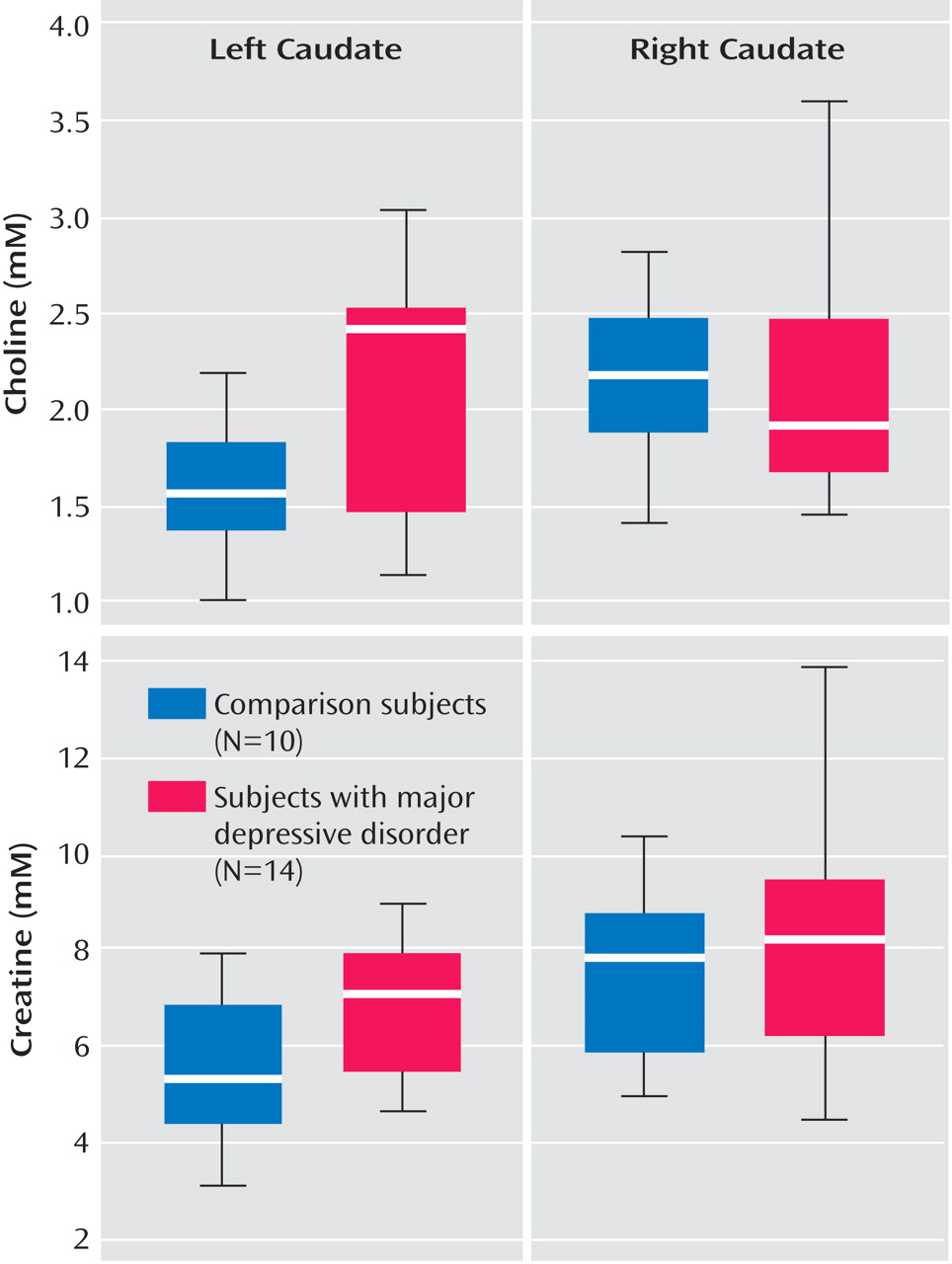

Neurochemistry

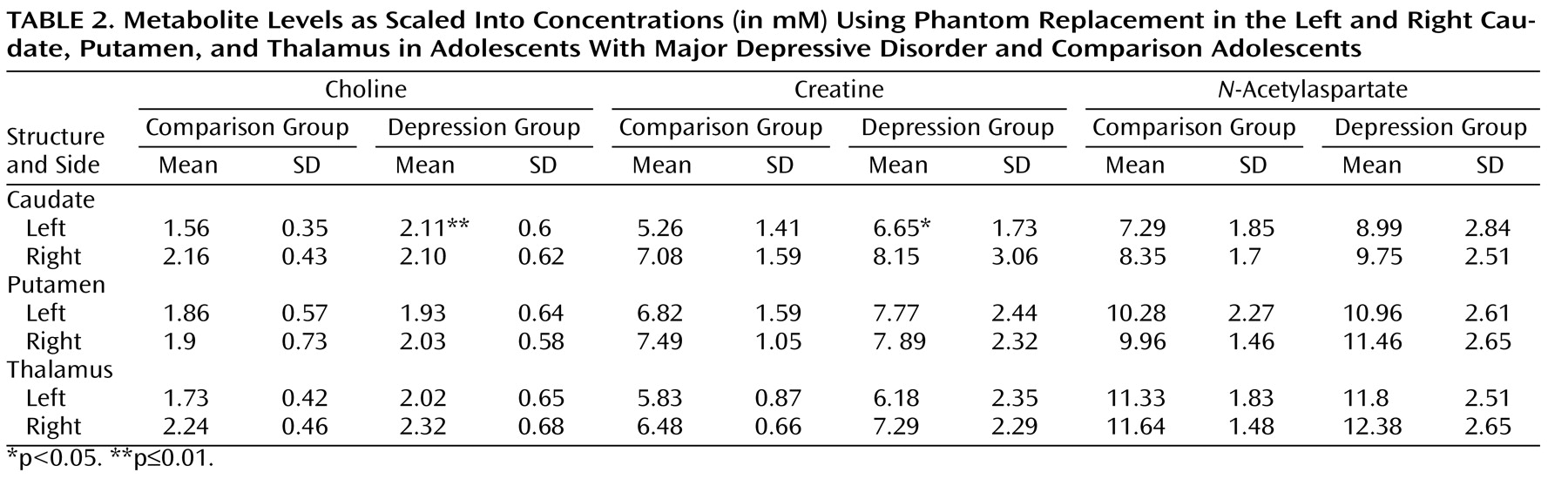

Patients’ and comparison subjects’ choline, creatine, and

N -acetylaspartate concentrations from the left and right caudate, putamen, and thalamus are compiled in

Table 2 . Relative to comparison subjects, adolescents with major depression had significantly elevated left caudate choline concentrations (2.11 mM versus 1.56 mM) and elevated left caudate creatine concentrations (6.65 mM versus 5.26 mM), as shown in

Table 2 and

Figure 2 .

No significant metabolite differences were found in the right caudate and in the left and right putamen and thalamus between the two groups. Similarly, the groups did not differ in metabolite concentrations averaged over the left and right caudate, putamen, or thalamus.

There were no significant differences between adolescents with major depression who were treated with psychotropic medications (N=8) and those who were medication naive or free (N=6) with respect to choline and creatine levels in the left caudate.

Because antipsychotic drugs may affect striatal chemistry and volume

(24,

25), we repeated the comparison excluding one adolescent treated with risperidone. The groups’ left caudate choline and creatine levels remained significantly different (F=5.58, df=1, 20, p<0.03, and F=4.92, df=1, 20, p<0.04, respectively).

Analyses of each brain region to examine interaction between major depression status and laterality (side of measure) was found to be significant for choline in the caudate (p<0.05), as shown in

Figure 2 .

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study of striatal neurochemistry in adolescent major depressive disorder. Using three-dimensional

1 H-MRS at high spatial resolution (0.75-cm

3 voxels) and a 3-T field, we found higher choline and creatine concentrations in the left caudate of adolescents with major depression relative to comparison adolescents. The hypothesis of increased choline bilaterally in the caudate and putamen and decreased striatal

N -acetylaspartate was not substantiated. Our finding is consistent with structural and functional neuroimaging studies documenting smaller caudate volumes and impaired blood flow in adults with major depression

(4,

5,

26,

27), as well as decreased caudate blood flow in depressed versus nondepressed patients with Parkinson’s disease

(28) .

Choline

Choline is an essential component of membrane lipids, phosphatidylcholine, and sphingomyelin

(29) . The

1 H-MRS choline peak comprises mostly the quaternary

N -methyl groups of glycerophosphocholine breakdown products (cytosolic compounds) and phosphocholine, the membrane precursors of phosphatidylcholine

(30) . The contribution of free choline to the signal is less than 5%, and that of the acetylcholine is negligible

(30) . Elevated choline is attributed to abnormal cell membrane metabolism, myelin breakdown, or changes in glia density

(31) .

Elevated choline observed in the left caudate most likely reflects accelerated cell membrane turnover due to glia impairment that has been linked to major depression

(32,

33) . Two mechanisms may lead to this process: 1) myelination abnormalities secondary to oligodendrocyte dysfunction, which have been implicated in major depression

(34) ; and alternatively or in addition, 2) astrocyte abnormalities

(35,

36) . Astrocytes may have a role in major depression via their role in CNS energy homeostasis.

Another possible mechanism for choline elevation involves the second messenger system. Phosphocholine, a major choline signal contributor and a metabolite of phosphatidylcholine, is an important source of diacylglycerol, the second messenger known to participate in intracellular signal transduction pathways

(29,

37,

38) hypothesized to contribute to the pathogenesis of major depression

(39) .

A third possible mechanism involving choline is in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, repeatedly implicated in biological studies of major depression. Glucocorticoids are proposed to affect phosphatidylcholine metabolism in neurons

(40) .

Despite choline’s role as a precursor for the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, its elevation in our study could not be dominated by cholinergic overactivity, which has been hypothesized in major depression

(41) . The small contribution of free choline and acetylcholine to the overall choline signal renders this possibility unlikely.

Choline has been the subject of a number of studies with diverse findings in other brain regions in pediatric major depression. Using similar three-dimensional

1 H-MRS, Farchione et al.

(42) found

increased choline concentrations in the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, whereas Caetano et al.

(43), in a later 8-cm

3 single-voxel study, reported

decreased choline concentrations in the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. In contrast, Mirza et al.

(44), using single 3-cm

3 voxels, found no differences in choline concentrations in the anterior cingulate cortex. Other studies examined metabolite ratios, also with conflicting results. Increased choline/creatine ratios were reported in the orbitofrontal and right prefrontal cortex of adolescents with major depression

(45,

46), and decreases were reported in the left amygdala

(47) . However, different brain regions may entail different neurochemical abnormalities in depression. Our observation is consistent with one prior report of no thalamic choline abnormalities in adolescents with major depression

(48) .

Creatine

This peak is a composite of overlapping creatine and phosphocreatine resonances, representing the high-energy phosphate reserves in the cytosol of neurons and glia

(21,

49) . Creatine’s elevation in

1 H-MRS has been attributed to altered metabolism

(50) . Our elevated creatine finding is consistent with altered metabolism, as suggested by earlier studies that found both decreased

(4,

5,

51 –

53) and increased

(7,

54) basal ganglia/caudate blood flow and glucose metabolism in major depression. Indeed,

31 P-MRS, capable of quantifying nucleoside triphosphates, has further implicated basal ganglia metabolism in major depression

(55,

56) .

Since most studies of mood disorders report ratios to creatine, rather than creatine concentrations, this metabolite is infrequently examined as a separate entity and thus far has never been examined in the caudate. The few studies that quantified creatine concentration in pediatric major depression focused on other brain regions; they reported decreases in the anterior cingulate cortex in adolescent major depression

(44) and no abnormalities in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex

(42,

43) . In adult major depression, the only study of creatine concentrations in the basal ganglia used low-spatial-resolution (27 cm

3 ) single-voxel MRS and did not identify any abnormality

(14) . Similarly, while we did not find an elevation in creatine levels in the striatum as a whole, our high spatial resolution enabled us to detect a focal elevation lateralized to the left caudate, underscoring the advantage of high field, sensitivity, and resolution. On the other hand, our finding of no thalamic creatine abnormalities in adolescents with major depression is consistent with one prior study

(57) .

The finding of elevated creatine levels in the major depression group emphasizes the limitation of using creatine as reference for metabolite measurement. Specifically, the creatine elevation could obscure a concomitant choline increase in a choline/creatine ratio. Similarly, a normal N -acetylaspartate level could be erroneously interpreted as a decline when the examined metric is the N -acetylaspartate/creatine ratio. Neither would be encountered when the analyzed metrics are scaled into concentrations using phantom replacement.

N- acetylaspartate

N -acetylaspartate is the second most abundant amino acid derivative in the mammalian brain

(11,

58) . It is almost exclusive to neurons and their processes and is therefore regarded as a surrogate marker for their viability

(59,

60) . Our hypothesis that

N -acetylaspartate levels would be decreased in adolescents with depression was not supported by our data. The increase of choline and creatine without a concomitant

N -acetylaspartate decline, as observed here, suggests accelerated membrane turnover but without neurodegeneration. While preliminary, this finding is concordant with those of other studies of pediatric major depression that found no

N -acetylaspartate decline, albeit in different brain regions

(42 –

45,

47) . In contrast,

N -acetylaspartate loss was reported in the caudate in adults with major depression in a small (N=7) study that analyzed

N -acetylaspartate/creatine ratios

(15) .

Lateralization of Caudate Metabolic Abnormalities in Major Depression

The lateralization of caudate neurochemical abnormalities in adolescent major depression fits with mounting evidence implicating the left hemisphere in depression

(61) . In a study focusing specifically on the basal ganglia

(9), volume differences between depressed and comparison subjects in the left putamen and globus pallidus correlated with illness length and frequency of depressive episodes. In other studies, patients with left caudate lesions were found to be more likely to have major depression than those with right basal ganglia or thalamic lesions

(62), and patients with left subcortical strokes, especially in the left caudate, had a significantly higher incidence of major depression than those with posterior subcortical or right basal ganglia lesions

(61,

63) .

Additional evidence for a role of the left caudate in depression is inferred from symptomatic correlation. Pillay et al.

(64) found a negative correlation between baseline depressive symptoms and left caudate volume. In adults with major depression, change in left caudate regional cerebral blood flow correlated with the emergence of depressive symptoms after interruption of paroxetine treatment

(65) . In cancer patients, increased left caudate glucose metabolism at baseline was associated with depressive symptoms 2 years later compared with patients who did not develop depression

(54) . Taken together, these findings emphasize the potential role of metabolic probes for early identification of major depressive disorder, perhaps even before the onset of clinical symptoms.

Although our findings of focal lateralized caudate abnormalities are consistent with prior studies of adult major depression, they should be considered preliminary in light of several limiting factors. First, the cohort size was relatively modest. Furthermore, because of the small sample size, we did not correct for multiple hypotheses, leading to possible type I errors. Second, most patients with major depression were on medication at the time of the scan. One treatment-response study

(66) identified significant change in the choline/creatine ratio only in a small sample of patients who responded to treatment (N=8) compared with those who did not respond (N=7). All the adolescents with major depression in our study were depressed at the time of their scan, and the eight patients taking psychotropic medications had not responded. Additionally, there were no metabolite differences between adolescents with major depression who were treated and those not treated. Nonetheless, since a medication effect cannot be ruled out, our findings should be viewed as preliminary.

We also did not examine the contribution of family history. This is of importance in light of strong evidence for familial transmission in adolescent major depression, which has fostered interest in familial major depression as a potentially distinct subgroup

(10) . While we did collect information regarding family history from parents, we did not conduct a comprehensive diagnostic interview, such as the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR.

An additional limitation was the use of intermediate rather than short echo-time 1 H-MRS. Using short echo-time 1 H-MRS would have enabled us to quantify myo -inositol, which reflects glia function. We chose to use intermediate echo-time 1 H-MRS, as it provides a better baseline and is superior with respect to reduction of macromolecule contamination.

In summary, our preliminary findings suggest focal left lateralization of caudate neurochemical abnormalities in adolescents with major depression, manifesting in increased choline and creatine, which suggests that membrane breakdown and impaired metabolism may play an early role in the disorder. Future studies should use larger cohorts and should strive to focus on specific clinical subgroups. Use of inclusion criteria such as familial major depression and psychotropic-naive status may improve the detection of neurobiological findings by decreasing phenotypic heterogeneity.