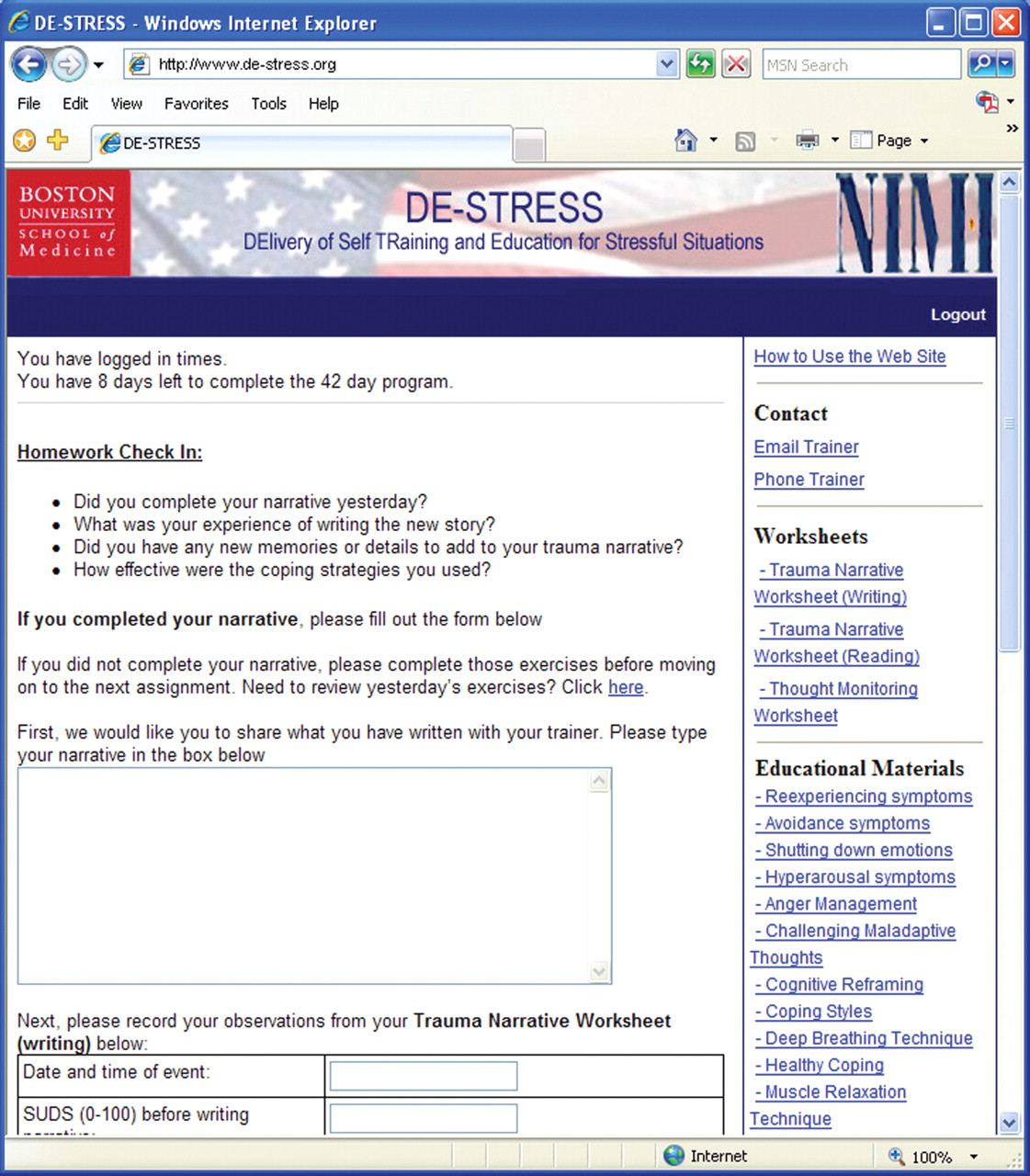

Participants

The patients were Department of Defense service members in the Washington, D.C., area who had PTSD as a result of the Pentagon attack on September 11th or combat in Iraq/Afghanistan. Exclusion criteria were 1) active substance dependence, 2) current suicidal ideation, 3) history of psychotic disorder, 4) <21 or >65 years of age, 5) PTSD or depression immediately before the trauma, 6) current psychiatric treatment, 7) marked ongoing stressors, and 8) inadequate social supports. Medications varied but were stable and maintained.

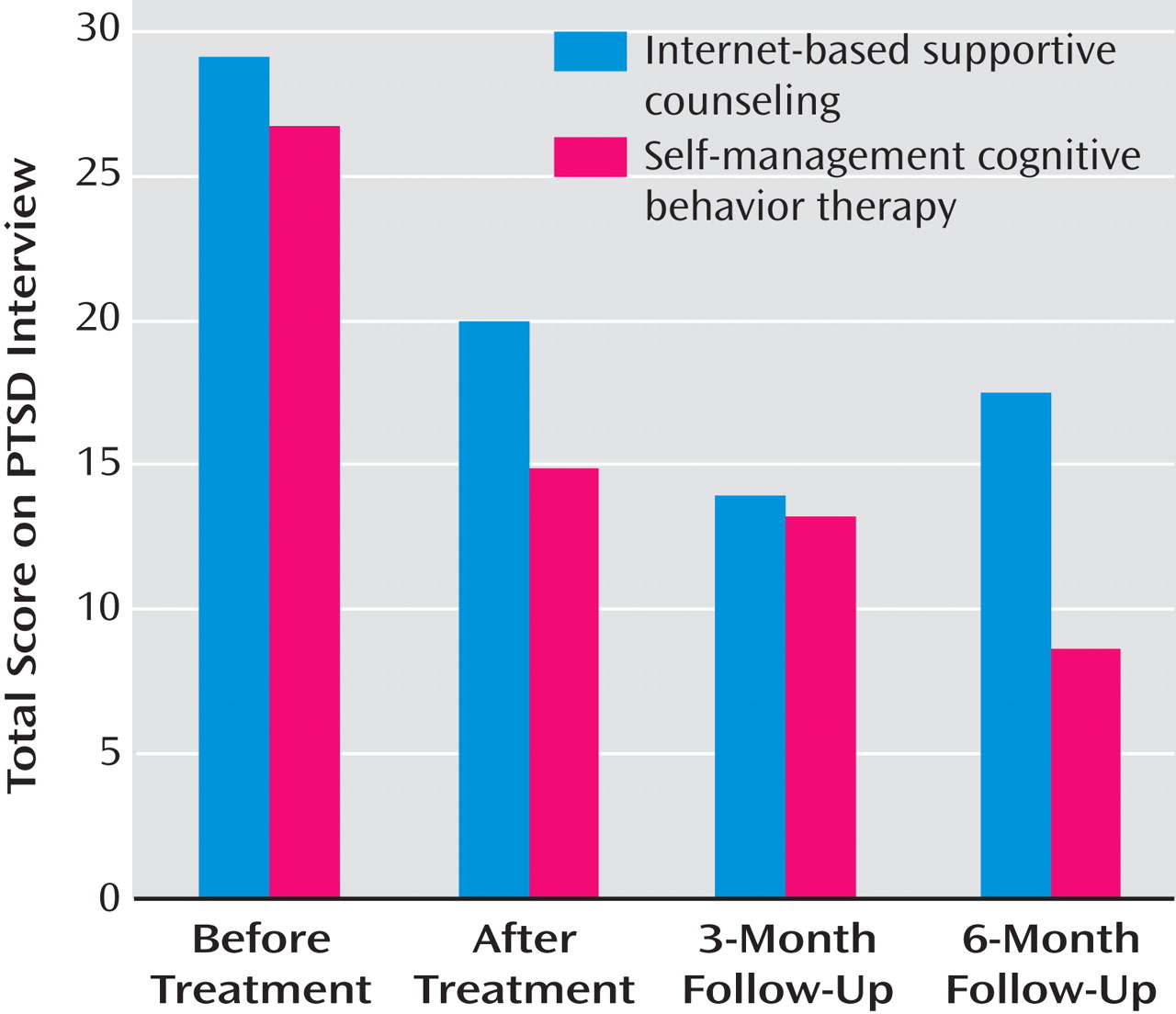

The participants were recruited through advertisements and presentations at Department of Defense sites. One hundred forty-one participants were screened; 41 were ineligible, 31 did not consent, and 26 could not be contacted for assessment. Forty-five participants were randomly assigned, and 33 completed treatment. Five patients dropped out after random assignment but before treatment; seven dropped out during treatment; 24 patients completed the 3-month follow-up, and 18 completed the 6-month follow-up (some service members were hard to locate). There were no differences in dropouts between the two study arms overall (likelihood ratio=1.19, df=1, N=45, p>0.05; at posttreatment: likelihood ratio=0.40, df=1, N=45, p>0.05) or at the 3-month (likelihood ratio=1.75, df=1, N=45, p>0.05) and 6-month follow-ups (likelihood ratio=0.43, df=1, N=45, p>0.05). Treatment arms did not differ in trauma type (likelihood ratio=1.99, df=1, N=45, p>0.05) (56% September 11th; 44% combat).

Completers were not different from noncompleters on gender (likelihood ratio=4.31, df=1, N=45), minority status (likelihood ratio=0.04, df=1, N=45), or baseline anxiety (t=1.01, df=45). Noncompleters were significantly older (t=2.18, df=43, p<0.05; 40.82 years old, versus 34.75 for completers) and more likely enlisted (likelihood ratio=4.59, df=1, N=43, p<0.05).

There were no differences in any variable between those who completed the posttreatment or 3-month follow-up assessments. In the self-management cognitive behavior therapy arm, those with 6-month follow-up data had higher socioeconomic status (t=2.09, df=22, p<0.05), lower baseline anxiety (t=3.23, df=21, p<0.01), and lower baseline PTSD scores (t=2.60, df=22, p<0.05), similar to other published studies

(7) . There were no differences between completers and noncompleters within the supportive counseling arm at both follow-up intervals.

Procedure

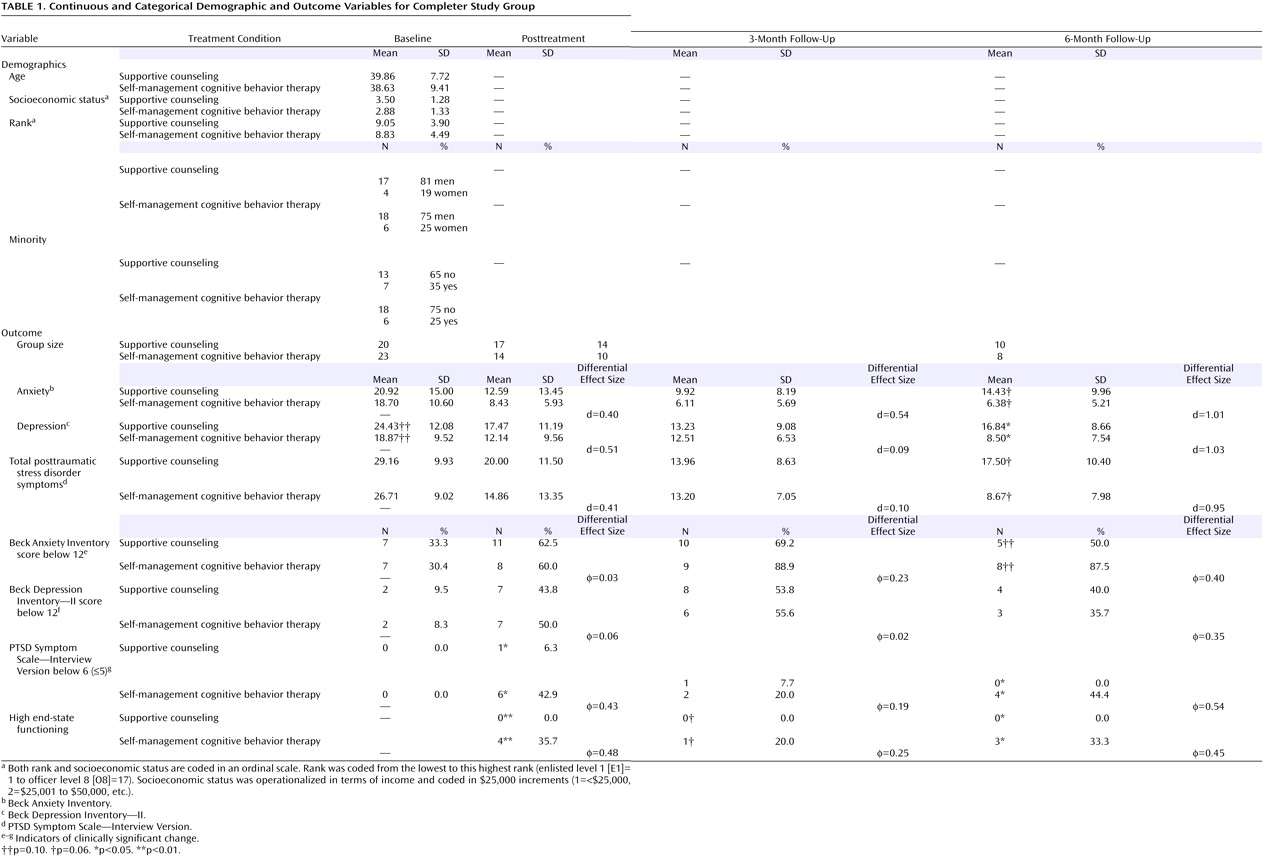

The participants provided written informed consent. They were evaluated at baseline, after treatment, and at 3 and 6 months after baseline. Each intervention arm was therapist-assisted and Internet-delivered and lasted 8 weeks, with 56 total possible log ons (daily). At each log on, the participants made online symptom ratings, reported homework compliance and homework content, acquired new content (or content was restated), and received a new homework assignment.

At baseline, each patient had an approximately 2- hour face-to-face meeting with the study therapist who, in addition to conducting the initial evaluation, introduced the study and intervention procedures; provided psychoeducation about PTSD and the benefits of stress management, a unique log-on ID, and password; and demonstrated the respective Internet sites. The patients in both arms also had periodic and ad lib study therapist contact via e-mail and telephone (they could also request a call back or an e-mail message from their therapist).

Study Interventions

Two highly specialized web applications were developed to automatize the delivery of the two interventions, collect outcome and process data (e.g., compliance), and assist study therapists and their supervisors to monitor patient participation (e.g., homework compliance). On each web site, patients had ad lib access to educational information about PTSD, stress, and trauma, as well as common comorbid problems and symptoms they might experience (e.g., depression, survivor guilt). The participants were also provided unrestricted access to information on strategies to manage their anger and sleep hygiene.

In order to reduce stigma and to emphasize the self-care aspects of the self-management cognitive behavior therapy, we employed the following title: DElivery of Self-TRraining and Education for Stressful Situations or DE-STRESS. The DE-STRESS acronym was particularly well received in the military context and by patients.

Internet-delivered self-management cognitive behavior therapy

The self-management cognitive behavior therapy was designed to teach patients strategies to help them cope and manage their reactions to situations that triggered recall of traumatic experiences (and negative affect and arousal). The intervention taught, promoted, and prompted stress and negative affect management strategies applied to a personalized hierarchy of trauma triggers (stressful contexts) through a series of homework assignments. The goal was to reduce PTSD symptom burden and to promote greater self-efficacy and confidence in coping capacities. The specific components of the self-management cognitive-behavior therapy were the following:

Self-monitoring of situations that triggered trauma-related distress (first 2 weeks)

The generation of a serial ordering (hierarchy) of these trigger contexts in terms of their degree of threat or avoidance (starting week three)

Didactics on stress management strategies that, once practiced (starting day 1), were used for

Graduated, self-guided, in vivo exposure to items from the personalized hierarchy (starting with the least threatening or least avoided item in week 3

Seven online trauma writing sessions (week 7, see below)

A review of progress (charts of daily symptom reports were presented), a series of didactics on relapse prevention, and the generation of a personalized plan for future challenges (week 8)

In the initial meeting with the study therapist, an initial hierarchy of stressful situations was generated collaboratively. It was assumed that most patients with PTSD are not sufficiently aware of what triggers the recall of trauma memories. As a result, in the first 2 weeks, the patients were asked to monitor their reactions to various stressful and demanding situations. After this period, the therapists assisted the patients in generating a final personalized stress hierarchy (with e-mail).

In the face-to-face session, the study therapists also provided initial training in two stress-management strategies (deep, slow diaphragmatic breathing and simple, progressive muscle relaxation) and initial training in simple cognitive reframing techniques (how to challenge unhelpful thought patterns and alter self-talk to effectively manage demanding situations). Subsequently, homework assignments were given online to further acquire these skill sets (e.g., see

Figure 1 ).

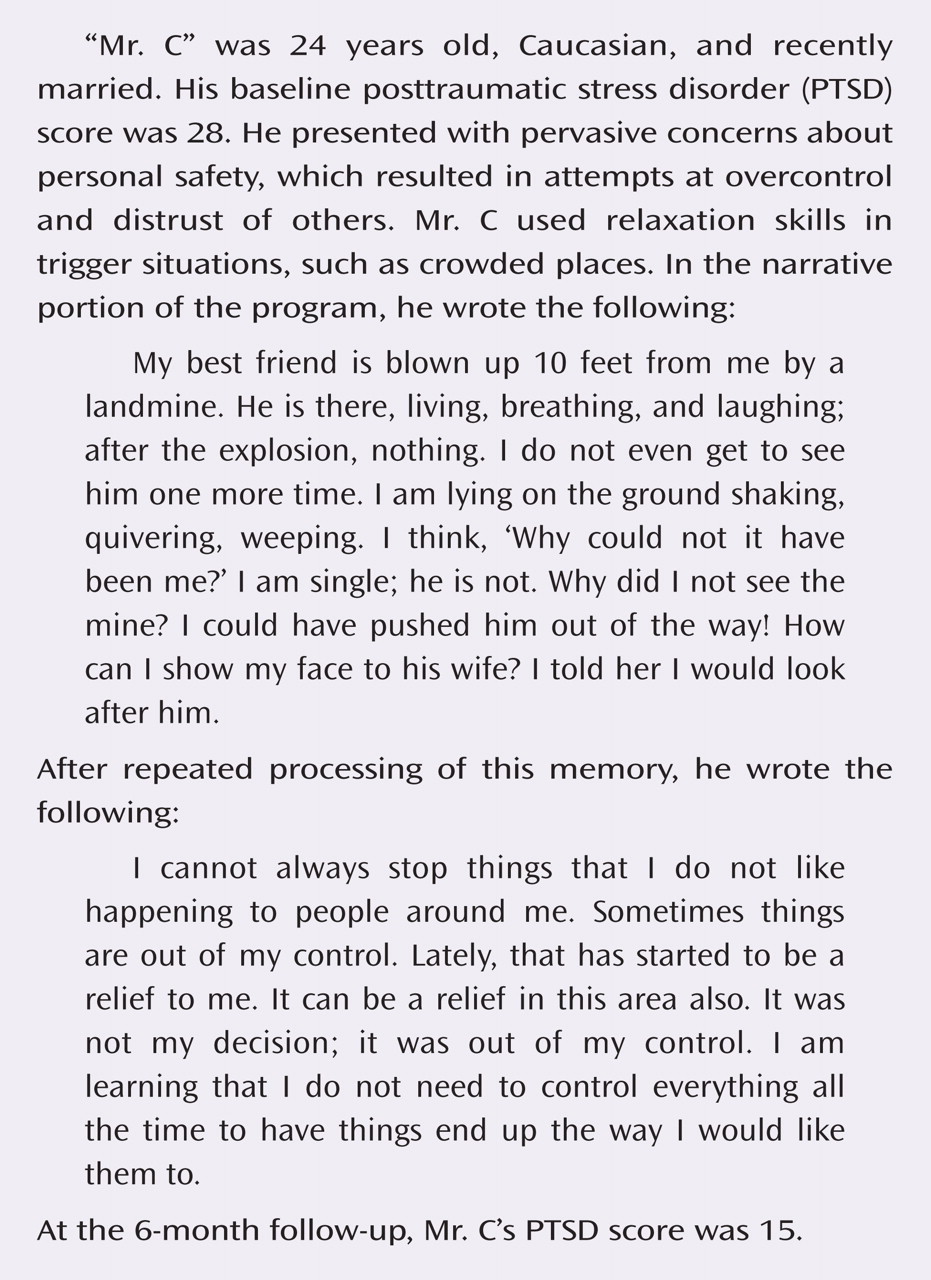

At the end of week 6, the study therapists had a planned phone conversation with the patients to determine if they were ready to do the trauma narrative portion of the self-management cognitive behavior therapy (no patients were deemed incapable or ineligible). In week 7, the participants were asked to write (type) a detailed first-person, present-tense account of a particularly salient and troubling traumatic experience. They were then asked to read their trauma narrative and encouraged to experience any emotions or memories that they may have been avoiding, while using coping skills acquired in the program. In the subsequent six log ons, the patients were asked to rewrite and process their traumatic memory, including any other memories that might not have occurred to them initially. The writing task is a variant of techniques employed in cognitive behavior therapy and cognitive processing therapy to target PTSD

(13,

16) . The goal was to promote mastery and to reduce avoidance, as opposed to maximizing emotional processing to promote extinction, as is the case in exposure therapy

(2) .

Internet-delivered supportive counseling

The majority of the supportive counseling intervention entailed participants being asked to self-monitor daily nontrauma -related concerns and hassles and online writing about these experiences. Psychoeducation materials were available about the psychological, emotional, and cognitive effects of trauma, but there was no skills training or prescriptions for proactive action. The supportive counseling group was asked to visit the web site daily to report their symptoms, read about stress and stress management, and write about current concerns. The web site allowed the participants to ask for an immediate telephone call from their therapists, and they were called periodically by their study therapist to check in on how they were doing and to answer any questions they might have about the self-help program. Through e-mail and the telephone, supportive counseling therapists were instructed to be empathic and validating, nondirective and supportive, and to focus on non-trauma-related present-day concerns. In week 8, patients in the supportive counseling arm were asked to plan ways of using what they learned in the course of the therapy from that point forward and to plan for future stressors; they also were shown graphs of the course of their progress (symptom reporting).