Psychiatry and religion often provide alternative explanations for many of life’s deepest and most mysterious phenomena. As a result, there has historically been tension between these two domains of understanding. Freud equated religion with neurosis (

1, p. 92) and even called it an enemy (

2, p. 160). Also, DSM-III used religion and spirituality to illustrate psychopathology and was criticized as portraying religion negatively

(3) . Conversely, religious thinkers have, at times, expressed skepticism toward elements of psychiatry. For example, Agostino Gemelli, who was himself a Catholic priest and psychiatrist, called psychoanalysis the “morbid product of Freud’s coarse materialism” and stated that Catholics should neither practice it nor be treated by it (

4, p. 344). Reflecting this tension, several empirical studies of psychiatrists’ religious characteristics have indicated that psychiatrists are measurably less religious than the general population

(5,

6), their patients

(5), and other physicians

(6) .

Some recent developments suggest that this historical antagonism is waning. Studies of the health effects of religion and/or spirituality have linked it to reduced depression and anxiety, increased longevity, and other physical and psychological health benefits

(7 –

9) . DSM-IV added a diagnostic category for religious and spiritual problems, therein recognizing that religious/spiritual beliefs are not inherently pathological

(10) . The 1995–1996 edition of the Graduate Medical Education Directory stated that all psychiatric residencies must include didactic sessions on religion/spirituality

(11) . Additionally, after surveying 425 psychotherapists (71 of whom were psychiatrists), Bergin and Jensen noted “sizable personal investment in religion,” which suggests a large degree of “unrecognized religiousness” in the profession (

12, p. 6).

These developments raise questions about how contemporary psychiatrists view the relationship between religion/spirituality and health. This is an important question because most Americans consider religion/spirituality to be an important part of their lives

(6), and some evidence suggests that patient outcomes improve when psychiatrists integrate therapy with patients’ religious beliefs. Psychiatrists’ views toward religion/spirituality likely shape the ways in which they respond to patients who bring religious or spiritual matters to the clinical encounter and may affect the types of care that patients receive.

Surprisingly, we know very little about psychiatrists’ beliefs in these matters. How do most psychiatrists respond when religion/spirituality issues emerge? Do psychiatrists encourage patients to discuss their religious/spiritual beliefs? In light of psychiatrists’ personal beliefs about religion, do they view religion/spirituality more negatively than other physicians? To explore these questions, we use data from a national survey of U.S. physicians from all specialties to compare psychiatrists’ and nonpsychiatrist physicians’ beliefs and observations regarding the influence of religion/spirituality on health and their attitudes and self-reported behaviors regarding religion/spirituality in the clinical encounter.

Results

Survey Response

Of the 2,000 potential respondents, an estimated 9% were ineligible because their addresses were incorrect or they were deceased. (Details of ineligibility estimation are reported elsewhere [reference

13 ].) Among eligible physicians, our response rate was 63% (1,144 of 1,820) and did not differ for psychiatrists compared to other physicians. Overall, foreign medical graduates were less likely to respond than U.S. medical graduates (54% versus 65%; Pearson’s χ

2 =14.2, df=1, p<0.01), and men were slightly less likely to respond than women (61% versus 67%; Pearson’s χ

2 =5.9, df=1, p=0.03). These differences were accounted for by assigning case weights. Response rates did not differ by age, region, or board certification. As shown in

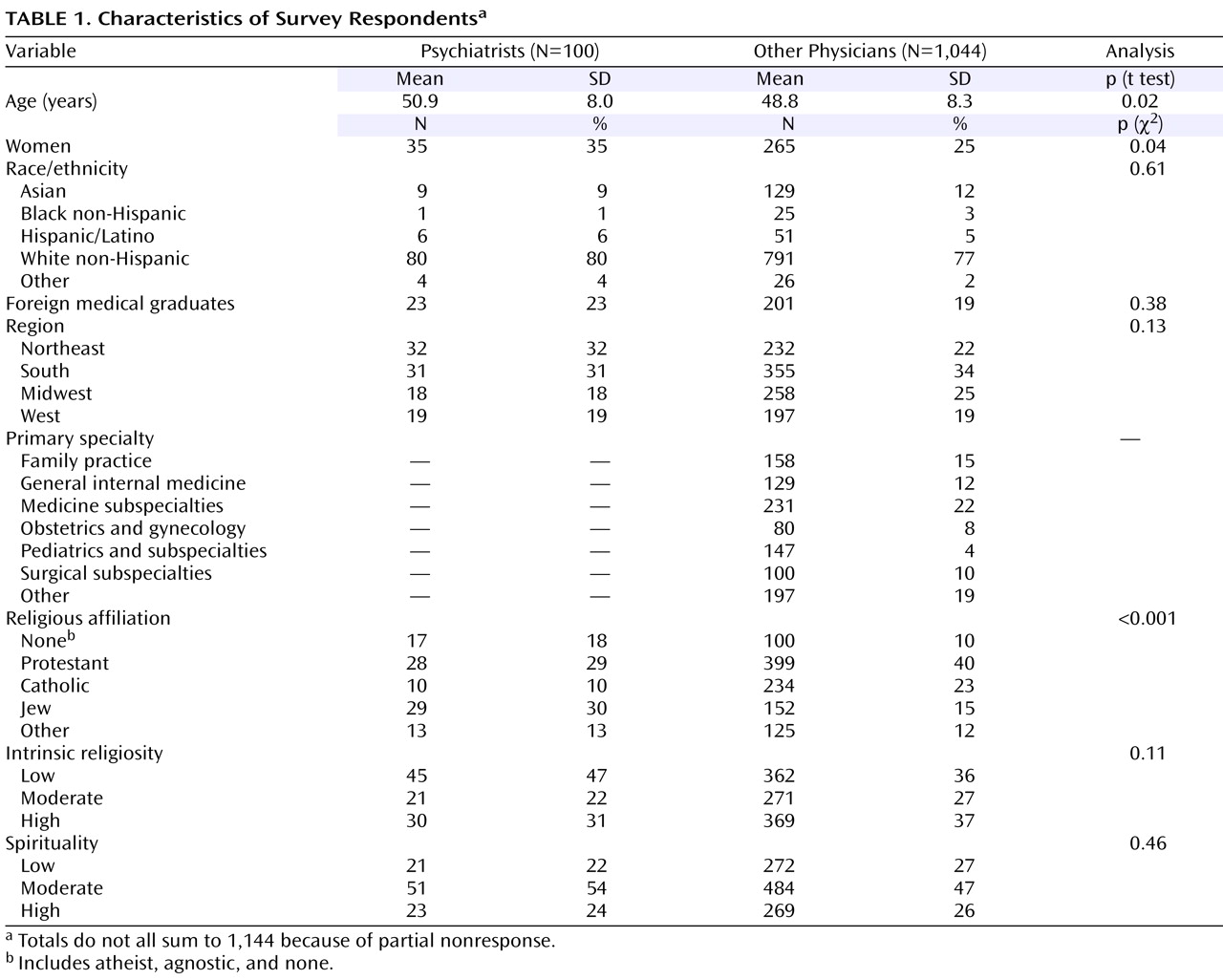

Table 1, psychiatrists were less religious, slightly older, and more likely to be women than nonpsychiatrists. They did not differ from other physicians with respect to race/ethnicity, foreign medical graduation, or region.

Religion and Spirituality in the Clinical Setting

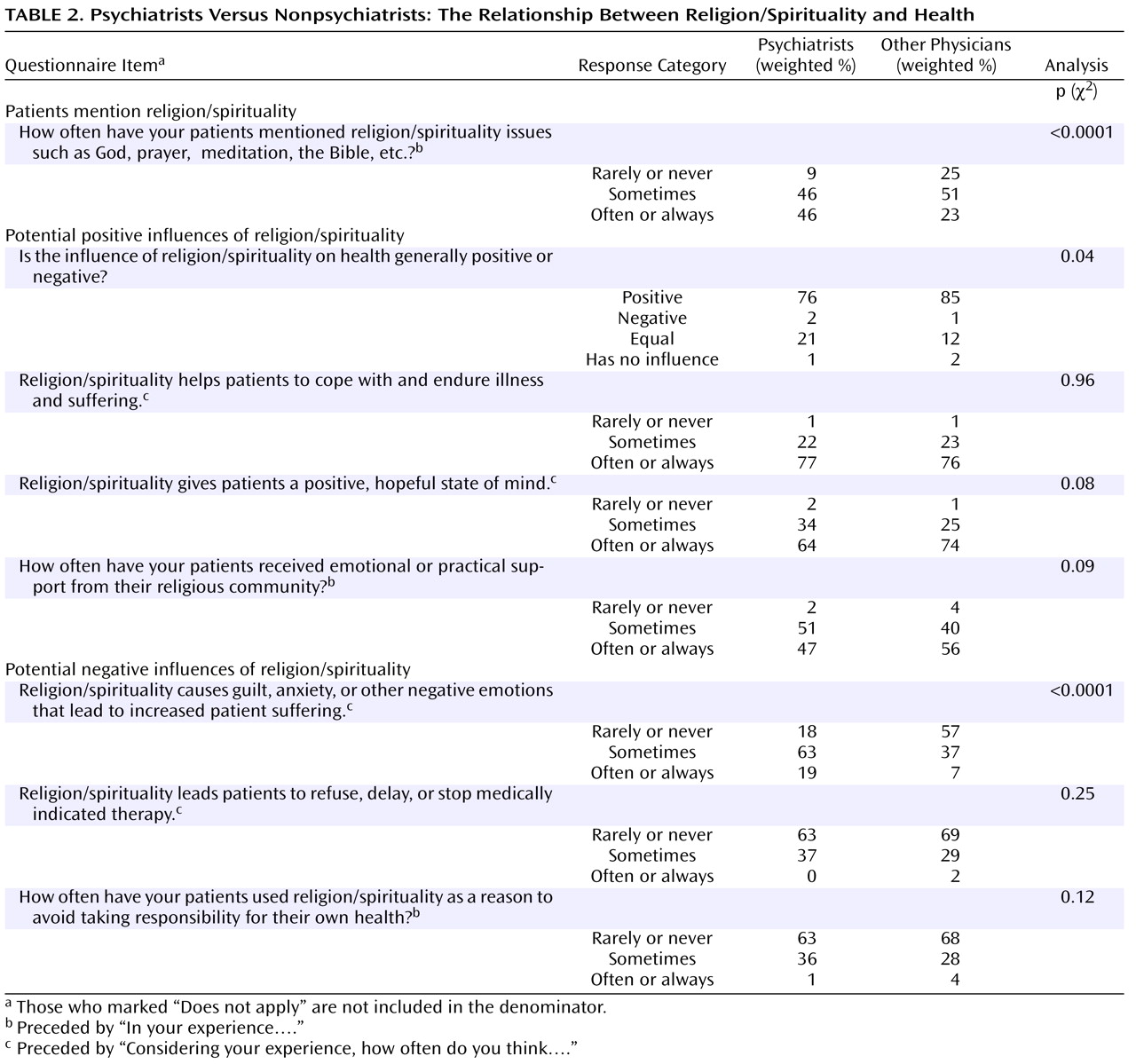

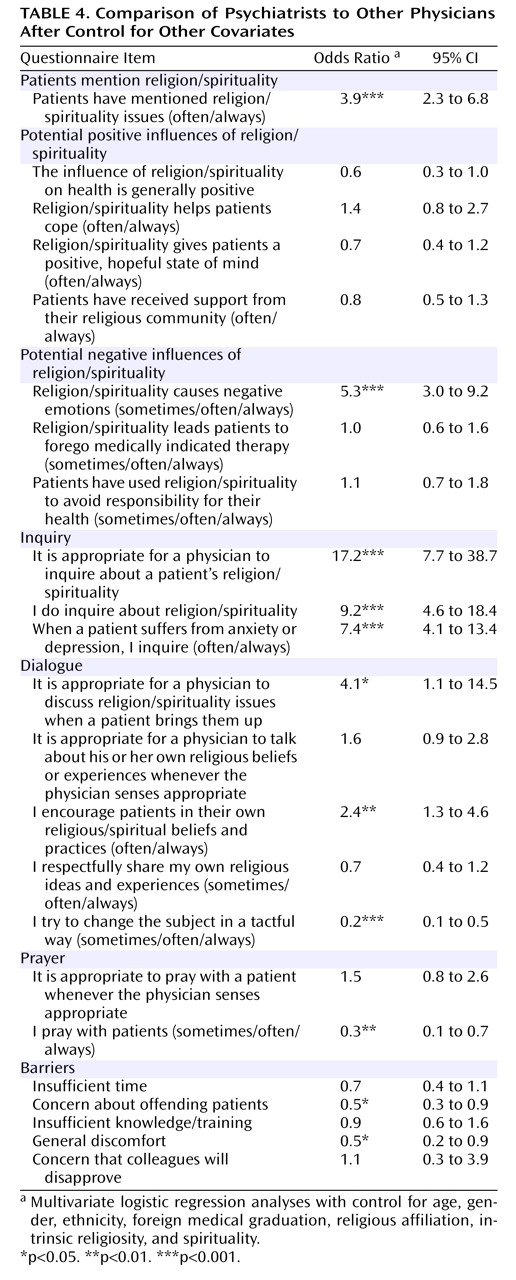

Psychiatrists are more likely than other physicians to address religion/spirituality in clinical settings. To begin with, they are more likely to report that patients often mention religion/spirituality issues (46% versus 23% report that patients do so often or always) (adjusted odds ratio=3.9, 95% confidence interval [CI]=2.3–6.8). They are also more likely to believe it is appropriate to inquire about a patient’s religion/spirituality (93% versus 53%; odds ratio=17.2, 95% CI=7.7–38.7), to report that they do inquire (87% versus 49%; odds ratio=9.2, 95% CI=4.6–18.4), and to report that they frequently inquire when patients suffer from anxiety or depression (44% versus 14% often/always; odds ratio=7.4, 95% CI=4.1–13.4).

Psychiatrists and nonpsychiatrists share many perceptions about the positive and negative influences of religion/spirituality. Most psychiatrists and nonpsychiatrists believe that religion/spirituality often helps patients to cope with and endure illness and suffering. They also believe that religion/spirituality gives patients a positive, hopeful state of mind. Approximately half of psychiatrists and nonpsychiatrists believe that religion/spirituality often or always provides a community that offers emotional or practical support. Only a fraction of psychiatrists and nonpsychiatrists indicated that religion/spirituality often leads patients to refuse, delay, or stop medically indicated therapy or motivates patients to avoid taking responsibility for their own health.

Three of four psychiatrists describe the influence on health as generally positive, which is not quite as high as the proportion of nonpsychiatrists who describe it so. However, more psychiatrists than nonpsychiatrists describe the influence as equally positive and negative (21% versus 12%), and psychiatrists are more likely to say that religion/spirituality sometimes causes guilt, anxiety, or other negative emotions that lead to increased patient suffering (82% versus 44% sometimes/often/always; odds ratio=5.3, 95% CI=3.0–9.2).

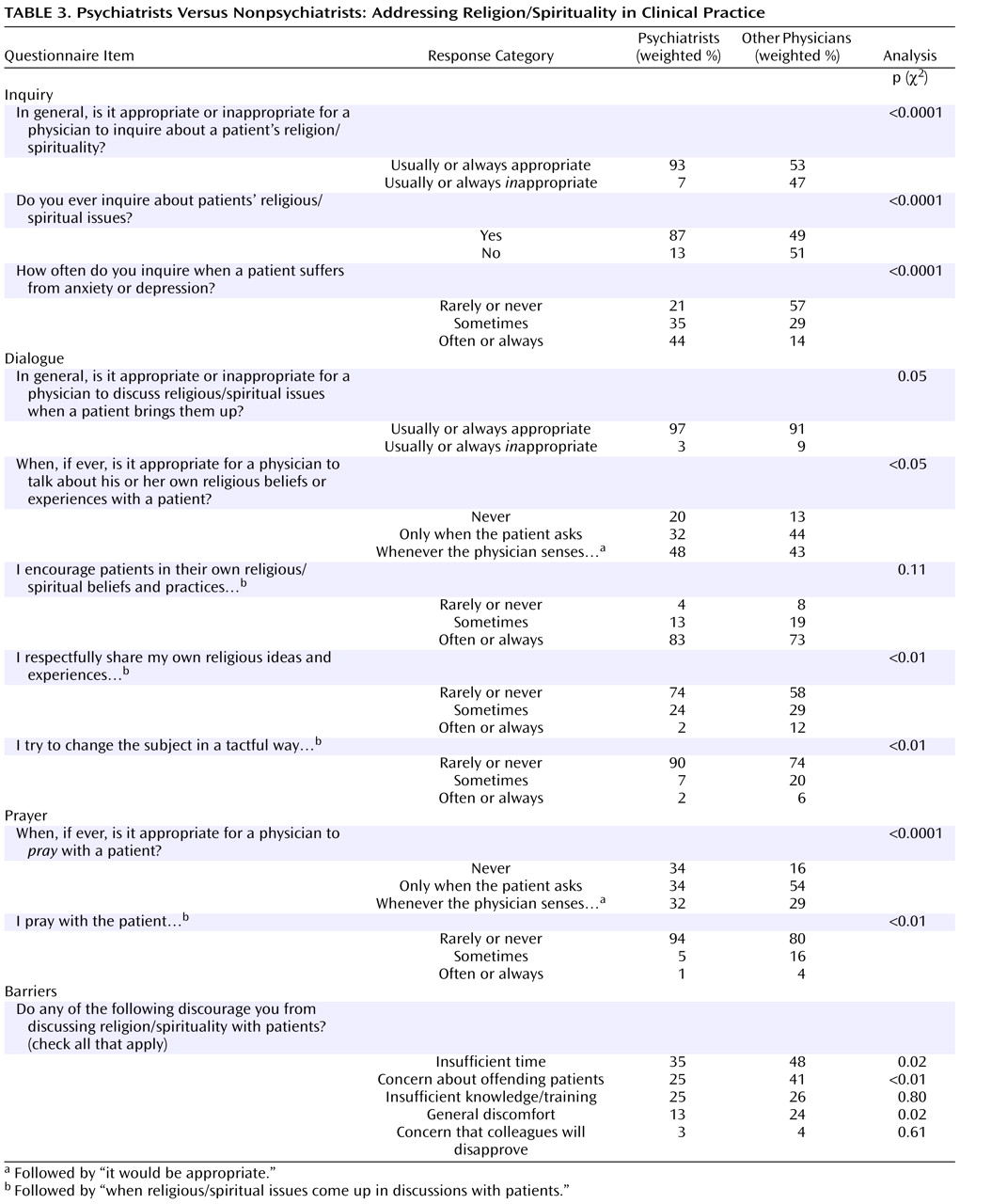

With respect to religion/spirituality in the clinical encounter, psychiatrists and nonpsychiatrists have points of similarity and dissimilarity (

Table 3 and

Table 4 ). Approximately half of the psychiatrists and nonpsychiatrists believe that the physician may talk about his or her own religious beliefs or experiences whenever he or she senses that it is appropriate. Only a minority of psychiatrists and nonpsychiatrists report sharing their religious ideas and experiences, suggesting that most of the time they do not sense it is appropriate. Psychiatrists are more likely than other physicians to believe it is appropriate for a physician to discuss religious or spiritual issues when a patient brings them up (97% versus 91%; odds ratio=4.1, 95% CI=1.1–14.5), more likely to often or always encourage patients in their own religious ideas and experiences (83% versus 73%; odds ratio 2.4, 95% CI=1.3–4.6), and less likely to change the subject away from religion or spirituality (9% versus 26% sometimes/often/always; odds ratio=0.2, 95% CI=0.1–0.5). Yet, while a third of psychiatrists and nonpsychiatrists believe it is okay for a physician to pray with the patient whenever the physician senses it is appropriate, in practice, psychiatrists are significantly less likely than other physicians to pray with patients (6% versus 20% sometimes/often; odds ratio=0.3, 95% CI=0.1–0.7).

In considering possible barriers to addressing religion or spirituality in clinical practice, psychiatrists were less likely to cite general discomfort or to be concerned about offending patients. Psychiatrists and other physicians had similar reports of being inhibited by insufficient time, insufficient knowledge/training, and concerns about disapproval from colleagues.

Discussion

This study suggests that psychiatrists may be more open to interacting with patients about religion/spirituality in the clinical encounter than other physicians. It also shows that psychiatrists generally have a positive attitude toward the influence of religion/spirituality on health, although they recognize that religion/spirituality can have negative effects

(19) . Several factors may contribute to this tendency. Psychiatrist George Engel’s biopsychosocial model for medicine

(20) recommends that psychiatrists (and other doctors) give attention to social and cultural dimensions of their patients’ illnesses. Thus, psychiatric training may predispose psychiatrists to attend to religion and to appreciate its connection to mental health. Psychiatrists may also be more likely than other physicians to encounter clinical situations in which a patient’s religious beliefs must be evaluated as part of the diagnostic process. Additionally, some mental illnesses are known to be associated with hyperreligiosity, and psychiatrists are at times asked to evaluate patients’ decisional capacity when religious beliefs collide with medical advice

(21,

22) . Each of these factors may increase psychiatrists’ openness to dialogue with patients about religious/spiritual matters.

The finding that psychiatrists generally acknowledge the relevance of religion/spirituality in inpatient care and value the importance of addressing it contrasts with the claim that psychiatrists ignore the spiritual realm

(23) but is consistent with other tendencies integrating religion/spirituality and psychiatry. The World Psychiatric Association recently established a section on psychiatry and religion

(24), medical schools and residencies have begun to teach about religion/spirituality

(24), and some writers have claimed mental health workers increasingly value close cooperation with community clergy and patient belief systems

(25) . These developments suggest that the historic division between psychiatry and religion may be narrowing.

Browning

(26) suggested a possible reason why psychiatrists, who remain less religious than other physicians, turn out to be more open to religion/spirituality than their physician colleagues. Drawing on William James’s statement that it is more worthwhile to study the results of different religions than to study their origins

(27), he suggested that psychiatrists’ openness may be rooted in an appreciation of religion’s effects rather than religion’s ontological value. Larson et al.

(28) made a similar suggestion, observing that professionals may have no personal religious beliefs and still recognize that religion has an important influence on human behavior. In this way, psychiatrists may remain less religious than others without necessarily being less open to addressing religion/spirituality in clinical settings.

One implication of these findings is that patients may increasingly have the opportunity to discuss religious/spiritual concerns with their psychiatrists. Since religious patients may benefit from treatments that accommodate their religious beliefs

(29,

30), outcomes could improve for this group. Improved outcomes, however, may depend upon the knowledge and expertise that psychiatrists bring to such discussions. Most psychiatrists receive little professional training about religious matters

(31), and psychiatric journals seldom deal with theological issues

(28,

32) . Psychiatrists thus risk speaking beyond the area of their expertise and/or without having explored their own biases for or against particular viewpoints

(30) . Because religion/spirituality is an important component of many clinical encounters, psychiatrists would benefit from increased professional training on religious/spiritual issues as well as an increased awareness of pastoral or theologically trained colleagues with whom they might consult when appropriate.

This study has several limitations. Undoubtedly some of the variation between psychiatrists’ and nonpsychiatrists’ responses is shaped by the distinctive goals and interactions inherent in the field of psychiatry. Physician-patient interactions in psychiatry differ from physician-patient interactions in other fields of medicine. If religion is a topic that simply shows up more often in a psychiatrist’s office and if psychiatrists handle the topic differently than other physicians (for example, reflectively listening rather than directing the patient), that could exaggerate the apparent differences between psychiatry and other medical fields. In addition, the boundaries between psychiatry, psychology, neurology, and counseling have not always been stable or well-defined

(26), so it is unclear whether these findings are limited to the field of psychiatry or may be generalized to include other fields of mental health. Concerning the survey, the response rate was better than average

(33), and we did not find substantial evidence to suggest response bias

(6,

13) . Nevertheless, religious and other characteristics may have systematically affected physicians’ willingness to respond in unmeasured ways. Moreover, self-reports are always imperfect measures of physicians’ actual practices.

In conclusion, this study reveals that psychiatrists are more open to engaging patients on religious and/or spiritual matters than are other physicians; thus, models that portray psychiatry and religion as conflicting fields may not be as accurate as previously assumed. The growing appreciation for the functional clinical importance of religion/spirituality in psychiatry requires continued examination and negotiation if psychiatrists are to wisely address religion and spirituality in their clinical practices.