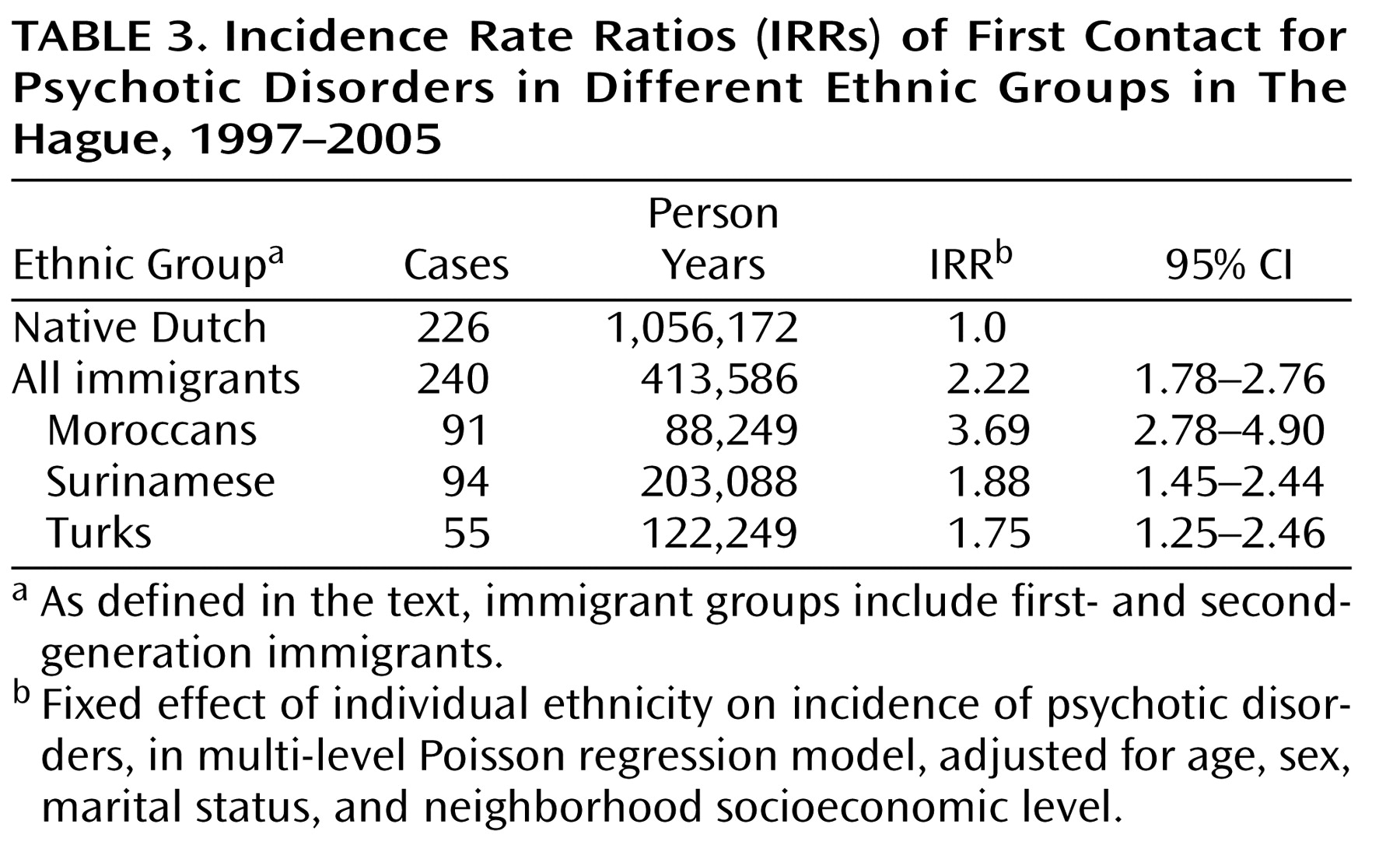

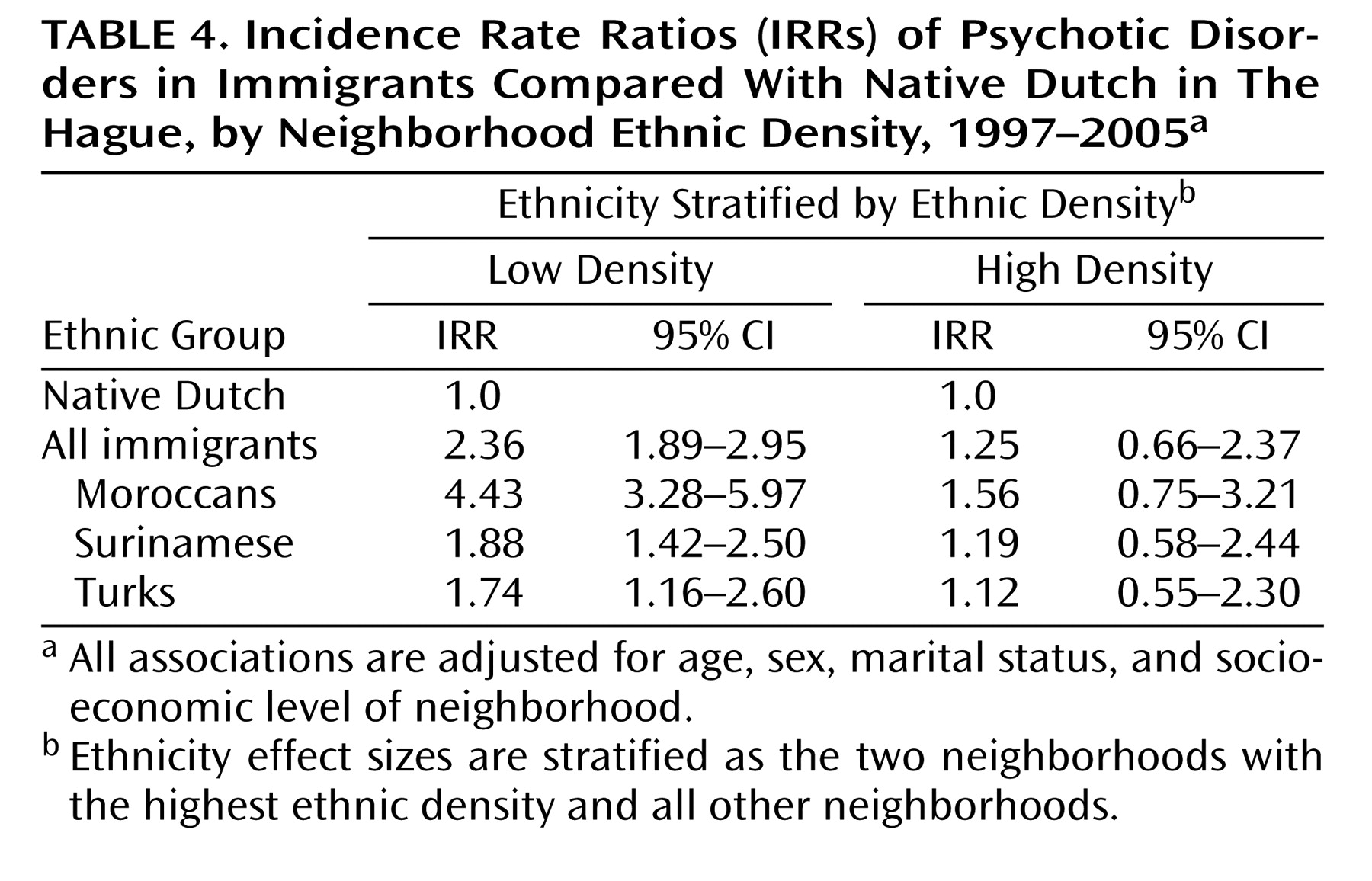

We found that the increased incidence of psychotic disorders among immigrants in The Hague depended strongly on neighborhood context. Compared with native Dutch, the incidence among immigrants was higher in those who lived in neighborhoods where their own ethnic group comprised a smaller proportion of the population. In low-ethnic-density neighborhoods, immigrants had a markedly increased incidence, whereas in high-ethnic-density neighborhoods, the incidence rate was not significantly higher than that of native Dutch.

Similar patterns were evident for Moroccan, Surinamese, and Turkish immigrant groups examined separately. The incidence rate of psychotic disorders was significantly increased only among immigrants living in low-ethnic-density neighborhoods (

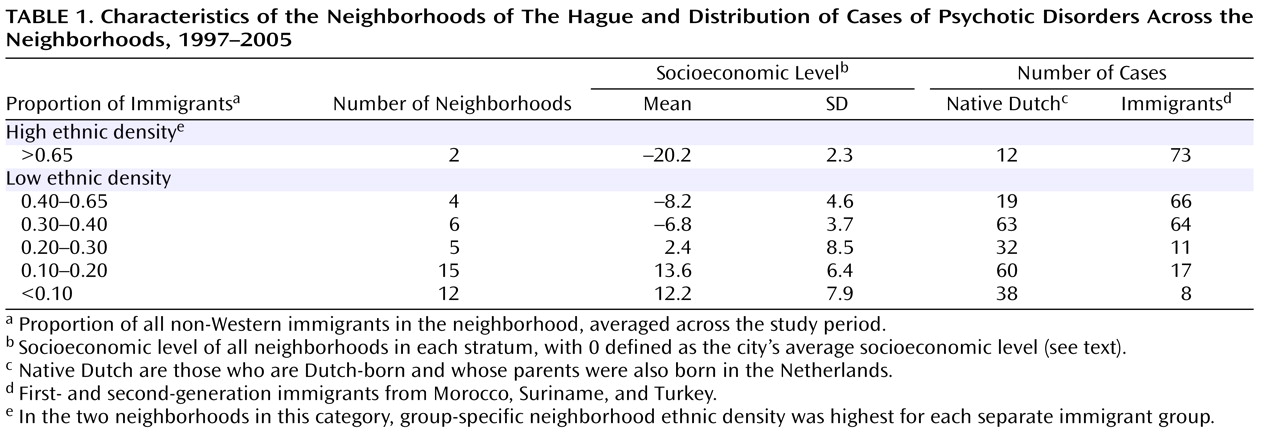

Table 4 ). The Moroccan group exhibited the highest incidence rates of psychotic disorders, and the difference between low- and high-ethnic-density neighborhoods was largest for Moroccan immigrants.

Our results are consistent with those from the seminal ecological study of Faris and Dunham during the 1930s in Chicago, which found higher hospital admission rates for schizophrenia among African Americans living in predominantly white neighborhoods

(7) . As noted earlier, our findings also extend those of Boydell and colleagues in London, who reported a “dose-response” relationship with an increasing incidence of schizophrenia in ethnic minorities as the proportion of such minorities in an area fell

(8) . The London study used appropriate multilevel statistical techniques and investigated treated incidence rates rather than hospital admission rates. Cases were identified by studying case records of a past 10-year period. The association between ethnic density and schizophrenia could not be fully investigated in that study, however, because it was not possible to investigate differential case ascertainment across neighborhoods or prodromal drift to low-ethnic-density neighborhoods and because information on ethnicity was limited. Ethnicity had to be assessed by a description in the case notes, and population data were not precise enough to study ethnic minority groups separately. Comparisons could be made between a “white” group and a “nonwhite” group. The latter group consisted largely of ethnic groups that may describe themselves as Black British, but although it may be hypothesized that such a shared identity is relevant to the ethnic density effect, there are many social, demographic, economic, and cultural differences among these ethnic groups. Finally, a recent study reported an association between ethnic fragmentation and the incidence of schizophrenia in southeast London as well as some evidence for an ethnic density effect, as the risk of schizophrenia was highest among ethnic minorities living in neighborhoods with the lowest ethnic density

(17) .

Building on these studies, we used a prospective incidence study involving a first contact with both secondary and primary health care services. We were able to assess the confounding effect of marital status

(18) and to conduct additional analyses to investigate alternative explanations for the findings. Moreover, we obtained population data that enabled us to calculate ethnic density as the proportion of the subjects’ own ethnic group in the neighborhood. This approach took into account the heterogeneity of ethnic minorities and allowed us to study each ethnic group separately.

Strengths and Limitations

This study was large enough to examine neighborhood variation in the incidence of psychotic disorders for several immigrant groups within a single urban area. The numbers of cases in both low- and high-ethnic-density neighborhoods were sufficient to test interactions between individual ethnicity and neighborhood ethnic density in a multilevel analysis. The numerators of the incidence rates were reliable, since the incident cases were derived from all sources of treatment in a defined geographical area and were assessed with a rigorous diagnostic protocol.

The denominators of the incidence rates were reliable. The person-years were not derived from a census but from a comprehensive, continuously updated municipal registration system. Registration with municipal authorities is compulsory for all individuals residing legally in the Netherlands and a prerequisite for obtaining essential documents and possible aid (e.g., income support). The data from a recent report on illegal foreigners in the Netherlands

(19) suggest that the number of Moroccan, Surinamese, and Turkish immigrants residing illegally in The Hague is less than 2,000. Thus, underenumeration of ethnic minorities is unlikely to explain the findings.

We were able to adjust for single marital status, which has been associated with higher rates of schizophrenia, particularly in neighborhoods with fewer single-person households

(18) . The results remained statistically significant, indicating that the ethnic density effect cannot be attributed to a greater probability of single marital status among individuals living in low-ethnic-density neighborhoods.

A limitation of the study may be that all psychotic disorders were included in the analysis rather than only schizophrenia. However, this approach minimized the potential for diagnostic bias. It has been suggested that immigrant patients with affective psychosis may present with more severe psychotic symptoms than nonimmigrant patients, which may lead to misclassification of affective psychosis as schizophrenia

(20) . In addition, many investigators argue that the validity of psychotic disorders as a group may be greater than that of schizophrenia, which is a diagnosis of uncertain validity

(21) . When we restricted our analysis to patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, we obtained similar results (adjusted incidence rate ratio, ethnic density interaction, all immigrants=0.96, χ

2 =6.36, df=1, p=0.012).

In the stratified analysis, we classified two neighborhoods with large immigrant populations as high density and the other 42 neighborhoods as low density. Since the threshold for the ethnic density effect is not known, other stratifications may be more valid. When we used alternative approaches to stratify ethnic density, the results were similar (data available from the first author).

Neighborhood ethnic density was assessed and investigated at the time of first treatment contact. In future studies, it might be feasible to collect longitudinal data on neighborhood context in childhood and adolescence. This approach could be used to verify that exposure to a low-ethnic-density neighborhood is antecedent to the onset of psychotic symptoms and to determine the developmental period during which neighborhood ethnic density is most important.

The socioeconomic status of the family of origin could not be adjusted for. Previous studies have found variable and modest associations of low family socioeconomic status and incidence of psychotic disorders

(22,

23) . In addition, it is difficult to see how low ethnic density would be related consistently to low individual socioeconomic status, because neighborhoods with the highest proportion of non-Western immigrants are deprived to a level not paralleled anywhere in the primarily Dutch neighborhoods in The Hague.

A paramount concern in the interpretation of these results is the potential for differences in case ascertainment between low- and high-ethnic-density neighborhoods. If immigrants who are clustered together in high-density neighborhoods are less likely to use Dutch health services when they develop psychotic symptoms, this could produce an artifactual ethnic density effect. For several reasons, however, this potential ascertainment bias is unlikely to account for our findings. Health insurance is compulsory for all individuals residing legally in the Netherlands, and immigrants visit their general practitioners more often than native Dutch do

(24) . Ascertainment in this study was an integral part of an early psychosis treatment program, which entailed active collaboration with general practitioners throughout the city. Furthermore, additional analyses conducted to detect such ascertainment bias were reassuring. Immigrants ascertained in low- and high-ethnic-density neighborhoods had a similar age at onset, and the variation in rates between low- and high-ethnic-density neighborhoods pertained to both first- and second-generation immigrants.

Our results could reflect a process of social selection rather than social causation. It is conceivable that individuals with psychotic disorders moved from high- to low-density neighborhoods prior to their first treatment contact, perhaps during the prodromal period of their illness. However, the mean proportion of the subjects’ own ethnic group in the neighborhood did not differ significantly between the immigrants who still lived with their parents (35% of the cases) and those who did not (mean density 11.62% and 10.68%, respectively; t=–0.82, p=0.41). Thus, there is no evidence that patients who had already left the parental home selected neighborhoods of residence with a lower ethnic density. One might still speculate that the parents of the immigrants who developed psychotic disorders had previously moved from high- to low-ethnic-density neighborhoods as a result of these parents’ genetic predisposition to psychosis. However, genetic risk for psychosis is not associated with upward social mobility

(25) . In The Hague, moving from a high- to a low-ethnic-density neighborhood generally means moving to a neighborhood with a higher socioeconomic level.

Implications

The most plausible interpretation of our findings is that our measure of neighborhood ethnic density captured a social experience that had a quantifiable impact on the incidence of psychotic disorders. Animal and human studies indicate that social experiences can affect brain development and the risk of mental disorders

(26,

27) . At present, we can only speculate on how the particular social experiences of immigrants could influence the emergence of psychoses. The finding of a similar ethnic density effect among first- and second-generation immigrants implies that ethnic density represents social experiences that are relevant for both generations.

Several mechanisms may be considered, which are not mutually exclusive. One possibility is that high ethnic density mitigates the pathogenic effects of discrimination

(8,

28) . We have reported elsewhere that the increased risk of schizophrenia for non-Western ethnic minority groups was associated with the groups’ experiences of discrimination

(29), and some studies have found that perceived discrimination may foster the emergence of psychotic symptoms

(30,

31) . Conceivably, living in a high-ethnic-density neighborhood could buffer the impact of discrimination and stigma

(32,

33) by enhancing positive identification with one’s own ethnic group, or it could reduce exposure to discrimination by reducing daily contact with the native Dutch majority.

Another possibility is that high ethnic density, which is likely to be associated with a greater probability of social support, increases access to normalizing explanations for anomalous perceptual experiences and abnormal beliefs that are present in individuals at high risk of developing psychosis

(34) . Whereas social isolation may contribute to the acceptance of a psychotic appraisal of these early abnormal mental states, a social network may have a normalizing function, thus preventing transition into psychosis

(35) .