Native Americans, as a group, have the highest alcohol-related death rates of any U.S. ethnic group

(1), and rates of alcohol dependence in the small number of tribes studied have been reported as 20%–70%

(2 –

6), higher than the epidemiological rate of DSM-IV

(7) alcohol dependence of 13% in the U.S. general population

(8) . Although research has delineated factors posing increased risk for the development of alcohol dependence in Native Americans

(9 –

13), little is known about factors associated with remission from alcohol dependence in this high-risk group.

Over the past two decades, a large body of research has focused on identifying factors associated with remission from alcohol dependence. Despite using different variables of interest, diagnostic criteria, diagnostic instruments, and interview and sampling techniques, generally consistent themes have emerged from these studies. Female gender, older age at assessment, current marriage, more robust social support, younger age at onset of alcohol dependence, less quantity of drinking, and less severity of drinking all tend to be associated with remission

(14,

18,

19) . In contrast to studies of treatment samples, which have generally shown less sustained remission in individuals with comorbid anxiety and affective disorders

(20 –

22), epidemiologic samples have not shown an association of those disorders with absence of remission

(14,

17) . Much of the literature on remission from alcohol dependence has focused on the role of treatment in remission; however, data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions

(14) have demonstrated that abstinent and nonabstinent recovery from alcohol dependence are similar in individuals who have received treatment and those who have not.

Results

Five hundred eighty participants were assessed for alcohol use and alcohol use symptoms. Two hundred fifty-four participants met criteria for lifetime DSM-III-R alcohol dependence with the added condition that three or more symptom criteria of dependence had to cluster during the same month or more in the participant’s life and the 254 participants had complete data for all variables used in the logistic regression and Cox proportional hazards analyses. Of these, 150 (59%) participants had complete remission from alcohol dependence.

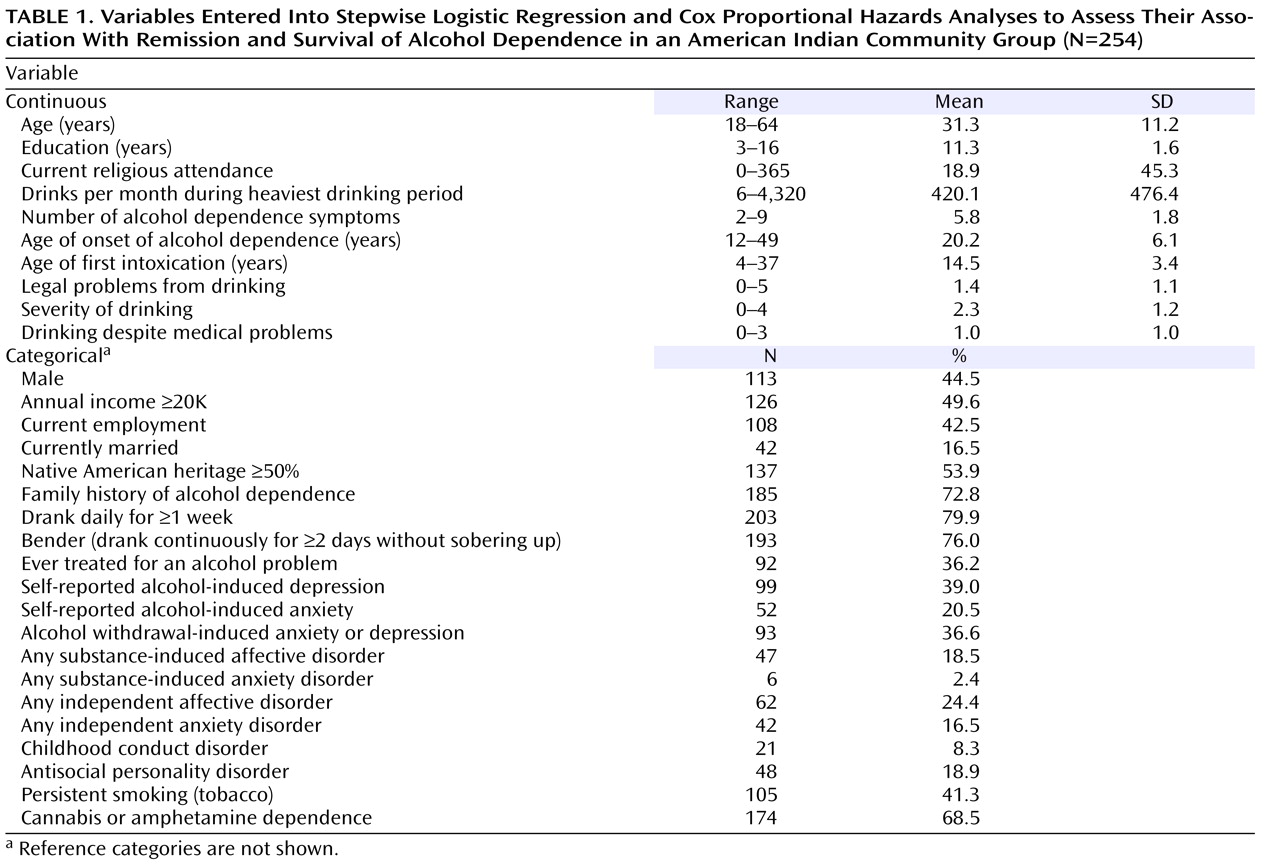

Demographic characteristics of the group as a whole resemble those of U.S. census data

(35) . Descriptive statistics for all demographic and clinical variables used in the logistic and Cox regression analyses are shown in

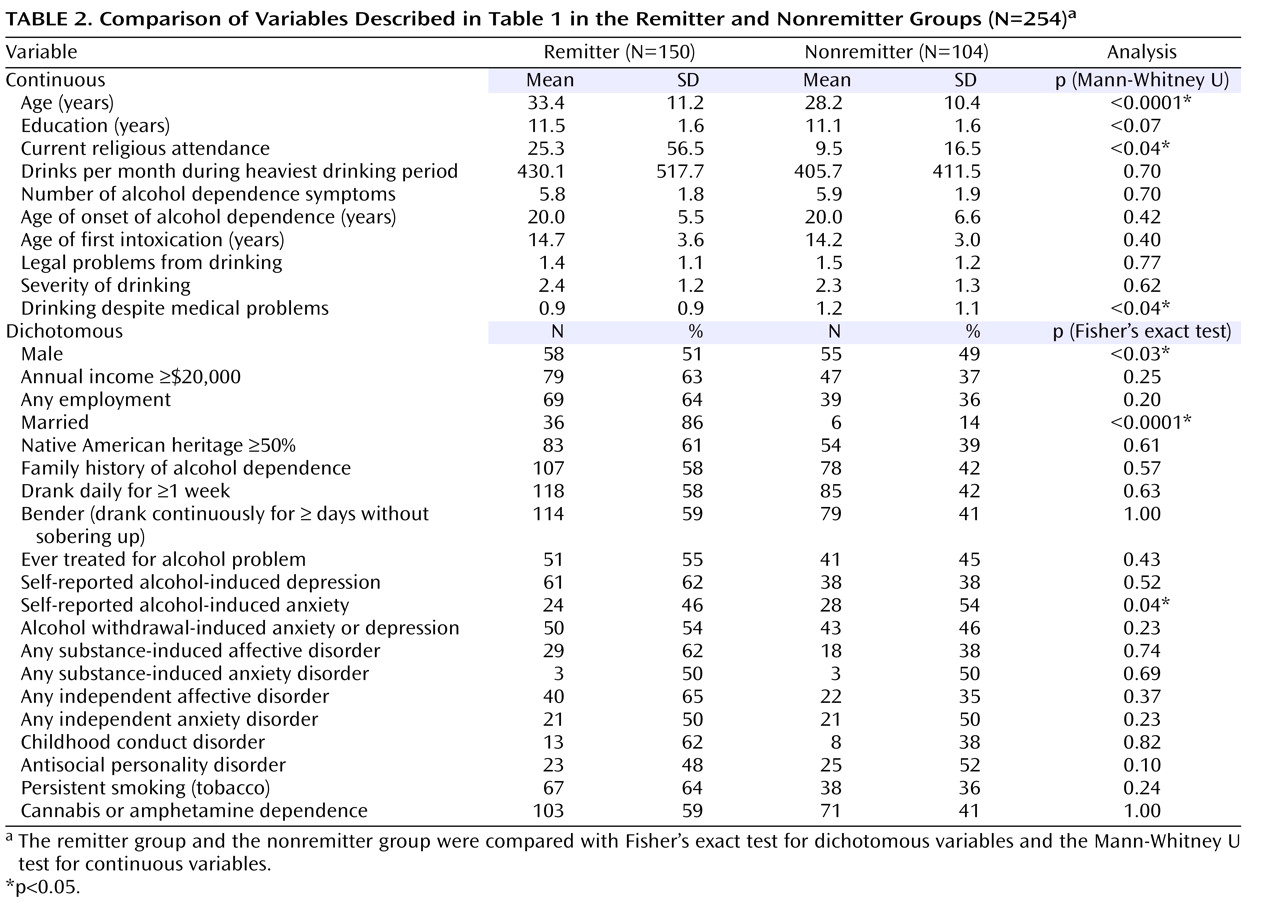

Table 1 . The results of univariate comparisons of each variable in the remitter versus nonremitter groups are shown in

Table 2 .

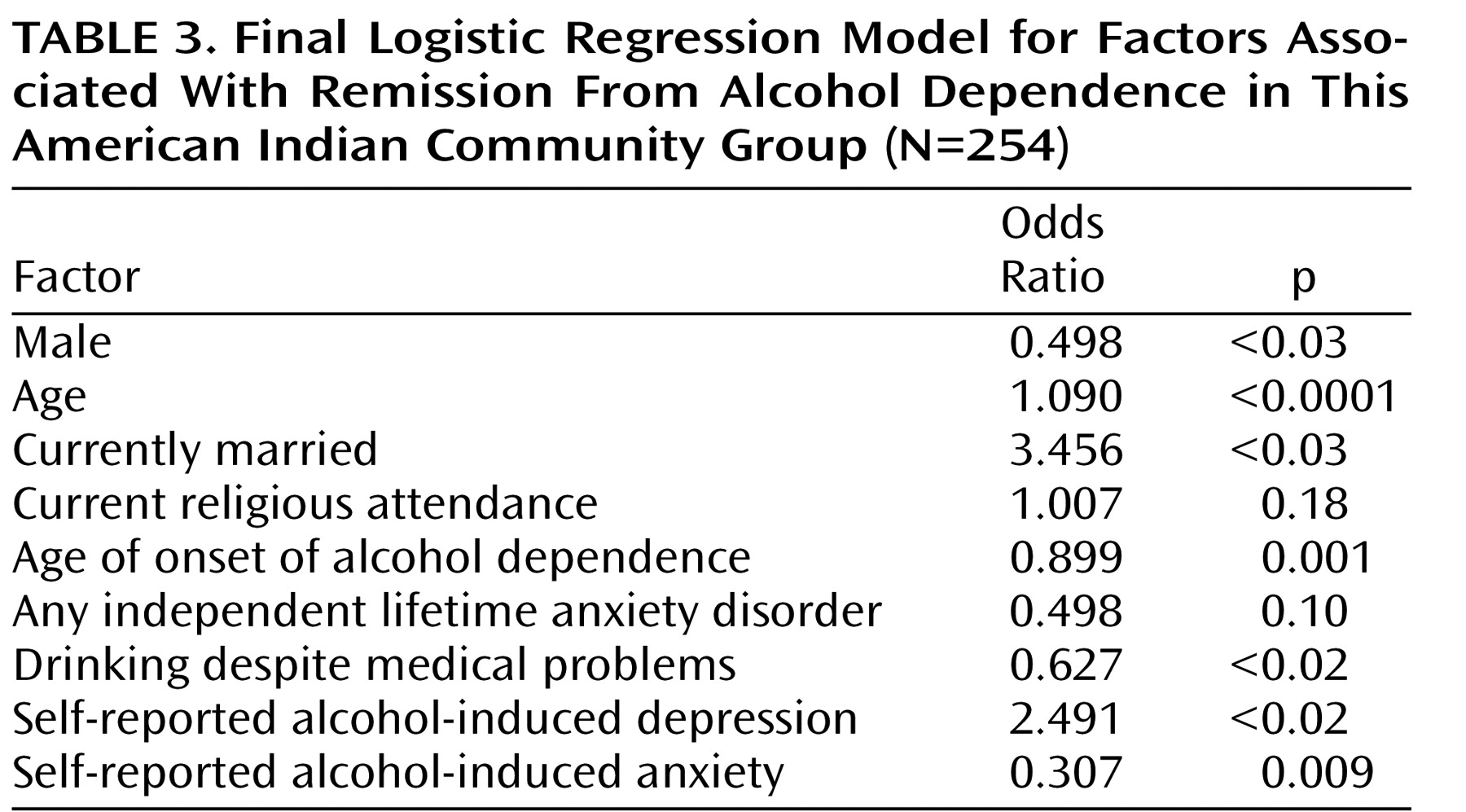

Stepwise logistic regression analysis of factors putatively associated with remission resulted in the final model shown in

Table 3 . Being older, female, and married; having an earlier age of onset of alcohol dependence; and having self-reported depression symptoms from drinking were significantly associated with remission. Continuing to drink despite medical problems and having self-reported anxiety symptoms from drinking were significantly associated with absence of remission. None of the other variables, including years of education, income, employment, first-degree family history of alcohol dependence, Native American Heritage, age of first intoxication, drinking daily for a week or more, having gone on benders of 2 days or more, quantity of drinking during the period of heaviest drinking, number of criteria of alcohol dependence, childhood conduct disorder, antisocial personality disorder, independent or substance-induced anxiety and affective disorders, cannabis or amphetamine dependence, persistent smoking (tobacco), having legal, endangering or alcohol use severity problems associated with drinking, and ever having had treatment for problems related to alcohol use, were associated with remission. The final model accounted for 30.2% of the variance in remission from alcohol dependence.

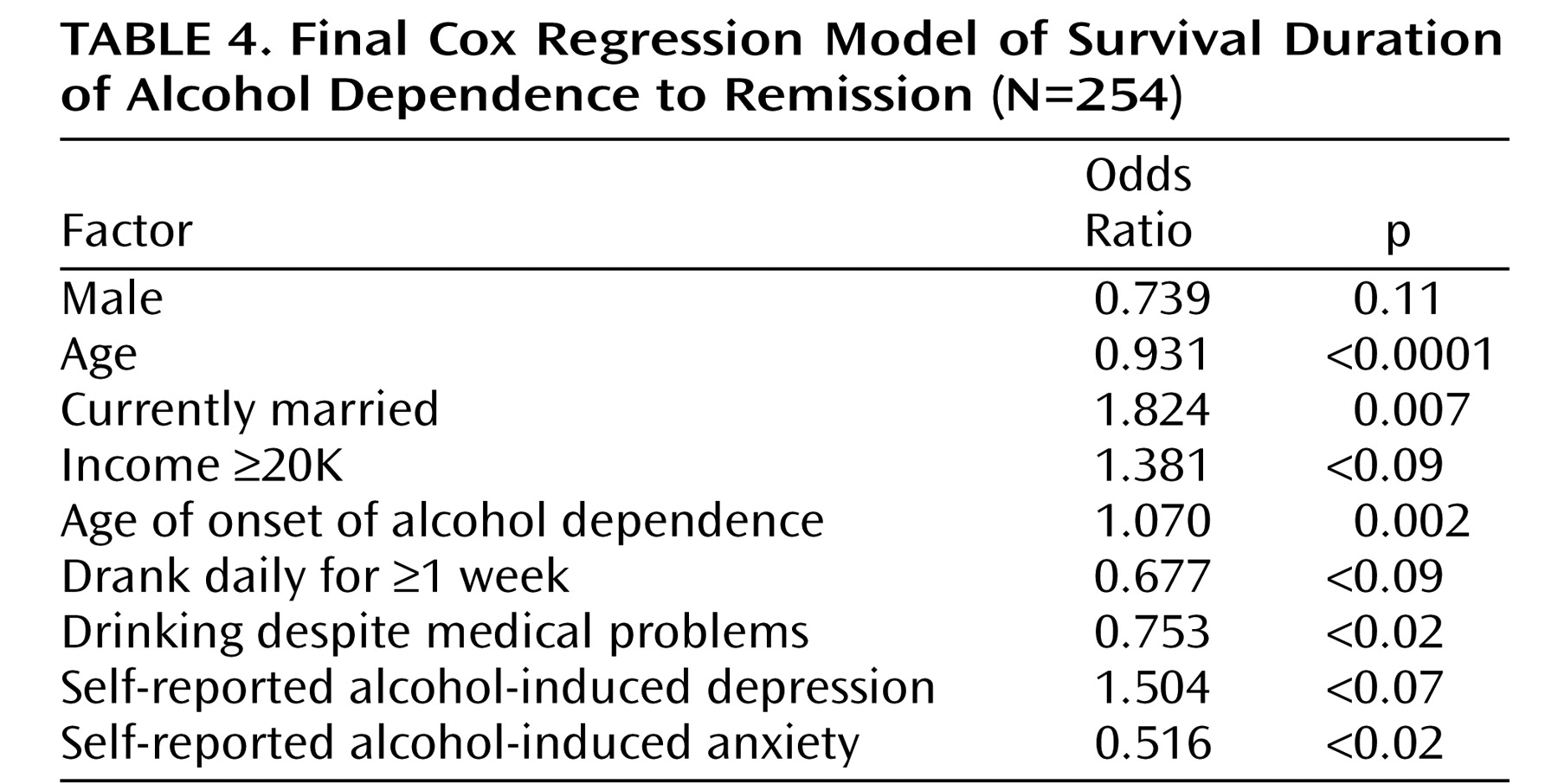

Evaluation of factors associated with survival time of alcohol dependence following diagnosis using stepwise Cox regression resulted in the final model shown in

Table 4 . Being younger, being married, having an older age of onset of alcohol dependence were associated with a shorter duration of alcohol dependence. Continuing to drink (despite medical problems) and self-reported anxiety symptoms from drinking were associated with a longer duration of alcohol dependence. Other factors, including gender, independent and substance-induced anxiety and affective disorders, childhood conduct disorder, antisocial personality disorder, cannabis or amphetamine dependence, other problems related to alcohol use, and treatment for alcohol problems, were not associated with survival of alcohol dependence.

Discussion

In this study, the rate of 6-month full remission from DSM-III-R alcohol dependence with 1-month clustering of 59% is comparable to the U.S. epidemiological rate of 1 year prior to past year, full remission from DSM-IV alcohol dependence of 48%

(14), the 1-year partial remission rate of 64% in a German representative population sample

(17), and the 1-year full remission rate from alcohol abuse and dependence of 53% found in Ontario, Canada

(16) . Despite the high rate of 1-month clustered DSM-III-R alcohol dependence of 49% in this group, the rate of full remission is comparable to studies of predominantly European ancestry populations.

Several factors associated with full remission in this American Indian group are consistent with factors associated with full remission in the general U.S. population. Our findings are consistent with the findings of Dawson and colleagues

(14) that abstinent and nonabstinent recovery in the general U.S. population are associated with female gender, increasing age, and being married, but not with tobacco use, dependent use of illicit drugs, and having any lifetime anxiety or affective disorder. Our findings are also consistent with Schuckit and colleagues

(30), who found that episodes of 3-month abstinence in a mixed treatment and nontreatment group were associated with female gender, older age, ever having been married, and younger age of onset of alcohol dependence, but not with a primary diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder.

Increasing likelihood of remission with advancing age in this American Indian group is consistent with the “aging out” phenomenon described in the Navajo

(5,

23) . Why “aging out” occurs in American Indians and other ethnicities is unclear. Alcohol dependence may biologically run its course in a proportion of alcohol dependents, and/or the accumulating psychosocial burden of alcohol dependence may prompt increasingly successful attempts at cutting back on drinking. In addition, as age advances, individuals with alcohol dependence, as well as those without, may develop new work, social, and family networks

(19) that play a role in reducing drinking. The consistent association of remission with marriage

(14,

18,

36) suggests that the social support and limit setting that can come from a spouse are important factors in promoting remission.

This study is also noteworthy for the factors that were not associated with remission. Several demographic variables, including current employment, years of education, economic status, frequency of attendance at religious services, first-degree family history of alcohol dependence, and Native American Heritage were not significantly associated with remission. Treatment for alcohol problems was not associated with remission in the group, a finding that may suggest that alcohol-dependent individuals find nontreatment as well as treatment-related pathways out of dependence, and/or individuals with a more refractory illness are those most likely to seek treatment.

In contrast to Dawson and colleagues

(14), we did not find that either the amount of alcohol use (as measured by quantity and frequency during the period of heaviest use), the severity of dependence (as measured by total lifetime dependence symptoms), legal/endangering problems from drinking, or alcohol use severity was associated with remission. These findings suggest that, at least in this group, increasing quantity of alcohol use and severity of dependence does not militate against remission. We did find that continuing to drink despite medical problems was associated with absence of remission, perhaps because the groups of individuals who continue to drink over extended periods tend to develop medical problems.

Of particular note is our finding that comorbid disorders, including independent anxiety and affective, substance-induced anxiety and affective, childhood conduct, adult antisocial personality, and cannabis- or amphetamine-dependence disorders, were not associated with a greater or lesser likelihood of remission from alcohol dependence. In general, these findings are consistent with epidemiologic studies of the general U.S.

(14) and north German

(17) populations. In treatment populations, comorbid disorders have generally been associated with increased likelihood of relapse following treatment

(20 –

22) . Although comorbid disorders are etiologically associated with alcohol dependence, the results of this study, taken together with those of Dawson and colleagues

(14) and Bischof and colleagues

(17), suggest that comorbidity per se is not etiologically related to remission from alcohol dependence in both predominantly Euro-American and American Indian samples. This finding, as well as the findings that severity of use and dependence are not associated with remission status, may justify some optimism that comorbidity and severity of illness do not militate against remission, at least in nontreatment-seeking populations.

A surprising and novel finding of this study is that self-reported depression and anxiety symptoms do play a significant role in increasing and decreasing, respectively, the likelihood of remission. These are not depression and anxiety symptoms occurring in the context of alcohol withdrawal, because a similar question asking whether withdrawal had ever caused depression or anxiety symptoms did not appear in the final logistic regression model. Why self-reported depression and anxiety caused by drinking should be significantly associated with remission, especially in light of the absence of association of independent or substance-induced anxiety and affective disorders with remission, is unclear. It may be that insight about the nature of the relationship between drinking and depression and anxiety is a critical element in promoting or inhibiting remission. Why self-reported alcohol-induced depression would increase while self-reported alcohol induced anxiety would decrease the likelihood of remission is also unclear. The former is consistent with findings that insight promotes increased compliance with treatment and remission of other psychiatric disorders

(37 –

39) . The latter is consistent with the hypothesis that individuals with alcohol dependence and alcohol-induced anxiety symptoms are more likely to continue drinking, perhaps as a means to self-medicate those symptoms. Both raise the possibility that education about the depression and anxious effects of alcohol and alternative ways of dealing with anxiety symptoms that accompany alcohol dependence may have an important role in treatment and community prevention programs in this high-risk population.

We also tested whether factors associated with remission of alcohol dependence were also associated with the survival of alcohol dependence. Two factors significantly associated with remission (being married and having self-reported depression symptoms from drinking) were also significantly associated with a shorter duration of alcohol dependence, and two factors associated with nonremission (continuing to drink despite medical problems and having self-reported anxiety symptoms from drinking) were also significantly associated with a longer duration of alcohol dependence. Advancing age and younger age at onset of alcohol dependence were both associated with increased likelihood of remission. However, both advancing age and younger age at onset of alcohol dependence were associated with increased duration of alcohol dependence. These data are consistent with previous findings in this group that alcohol dependence runs a typical clinical course that includes duration as well as symptom profile

(3) . These data are not consistent with the notion that, from the standpoint of remission, there may be two groups of alcohol-dependent individuals: those with early onset who have a shorter course of alcoholism and those with later onset who have a longer course, which has been suggested for other populations

(16,

40) .

The results of this study should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, our findings may not generalize to other American Indians or be representative of all American Indians. Second, we used cross-sectional and retrospective data. Cross-sectional data include individuals who will remit during their lifetimes but have not yet remitted, and so the odds ratios for factors associated with remission may be higher or lower than they would otherwise be. Retrospective data suffer from recall bias, which may include a reporting bias that results from having remitted or not remitted, advancing age, and other variables used in the logistic regression analysis. A prospective study of the development of alcohol dependence and its clinical course would provide a more powerful model for remission in this population. Third, comparisons to other populations of alcoholics may be limited by differences in sampling techniques as well as varying genetic and environmental variables in different populations. Fourth, in this study, we chose to examine 6-month full remission from DSM-III-R alcohol dependence with the added condition that three or more criteria of alcohol dependence had to “cluster,” that is, occur in the same month or longer in the participant’s life. In this group, 17.1% of the group had a lifetime diagnosis of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse. If we had chosen another definition of remission, had examined DSM-III-R alcohol dependence without 1-month clustering, or included alcohol dependence and alcohol abuse as a unitary alcohol use disorder diagnosis, we might have found that other variables were associated with remission from and survival of the alcohol use disorder. Fifth, we did not assess two important anxiety disorders, generalized anxiety disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. If we had information on those diagnoses, our findings on the association of remission from and survival of alcohol dependence with anxiety disorders might have been different. Finally, a higher mortality rate among nonremitters than remitters may have skewed variables associated with nonremission, rendering them more or less associated with nonremission and survival of alcohol dependence than they would be if potential participants who had died before being interviewed could have been sampled. Despite these limitations, this report represents an important first step in identifying factors associated with remission from alcohol dependence in this high-risk group.