Data Sources

The electronic databases MEDLINE, ClinPSYC, PsychLit, EMBASE, PILOTS, LILACS, PSYNEBS, SocioFile, CINAHL, and the Cochrane Depression, Anxiety, and Neurosis Group Trials Register were searched until July 2007 using the Cochrane optimal randomized controlled trial search strategy combined with the following keywords: PTSD, trauma, acute stress disorder, acute posttraumatic stress disorder, acute post-traumatic stress disorder, early intervention, early psychological intervention, preventative, prevention, PTSD prevention, crisis, crisis intervention, psychological first aid, cognitive, behaviour, behavior, behavioural, behavioral, cognitive-behavioural, cognitive-behavioral, exposure, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, psychological, psychotherapy, psychodynamic, stress inoculation, relaxation, anxiety management, psychoeducation, collaborative care, collaborative intervention, recovery, facilitating recovery, critical incident stress debriefing, debriefing, critical incident stress management, counseling, counselling, supportive counselling, and supportive counseling. Manual searches were undertaken of the Journal of Traumatic Stress and the Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology . Reference lists of studies identified in the search, related review articles, and management guidelines were scrutinized. Internet searches of known web sites and discussion forums were conducted, and key researchers in the field were contacted to determine whether they were aware of other relevant studies.

Study Selection

All abstracts were read independently by two of the reviewers to determine whether they potentially met the inclusion criteria. If either reviewer thought the study potentially met the criteria, the full manuscript was obtained and read independently by three of the reviewers. To be included, a study had to be a randomized controlled trial that considered one or more defined psychological interventions or treatments (excluding single-session interventions) aimed at preventing or reducing traumatic stress symptoms following events that appeared to fulfill DSM-IV criterion A1 for PTSD or acute stress disorder in comparison with a placebo control, other control (e.g., usual care or waiting list control), or alternative psychological treatment condition. All studies had to have been completed and analyzed by September 2007. Presence or absence of symptoms, sample size, language, and publication status were not used to determine whether a study should be included. The review considered studies involving adults only.

Data Synthesis

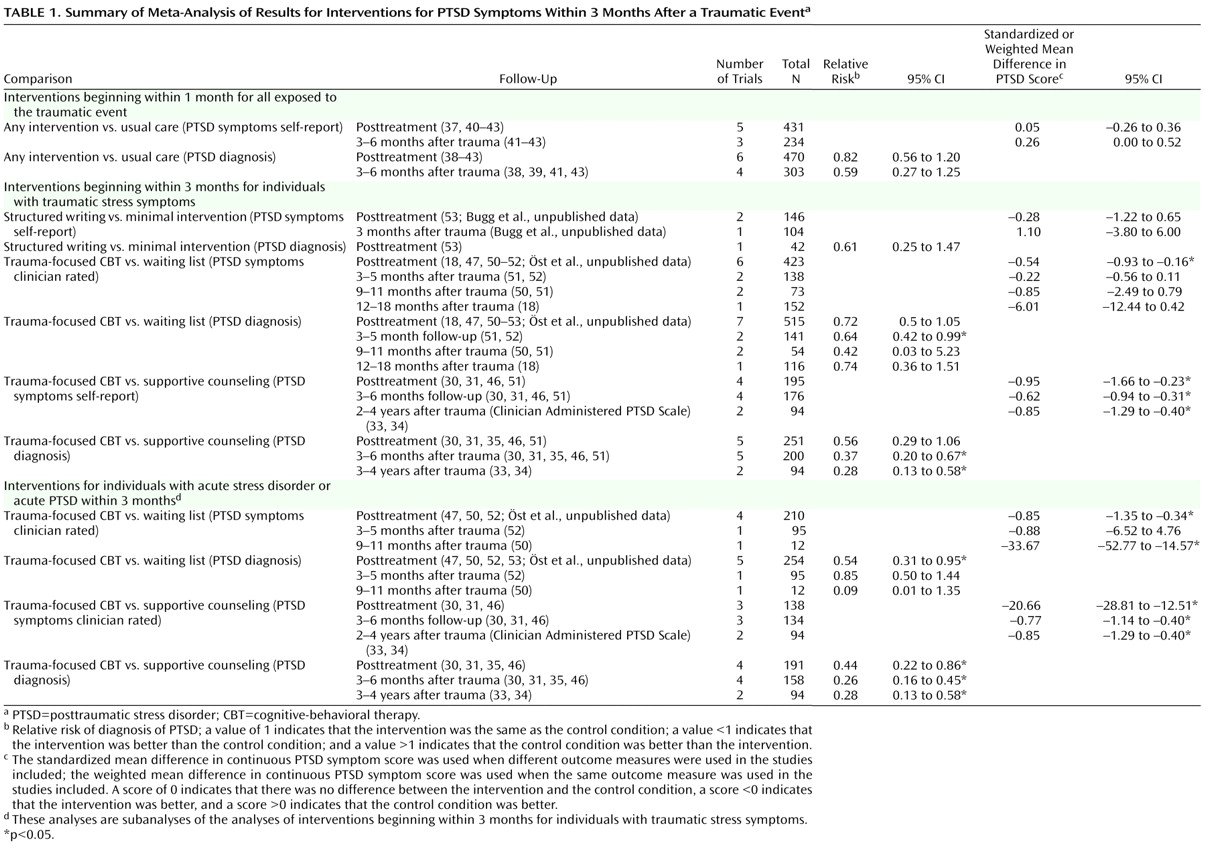

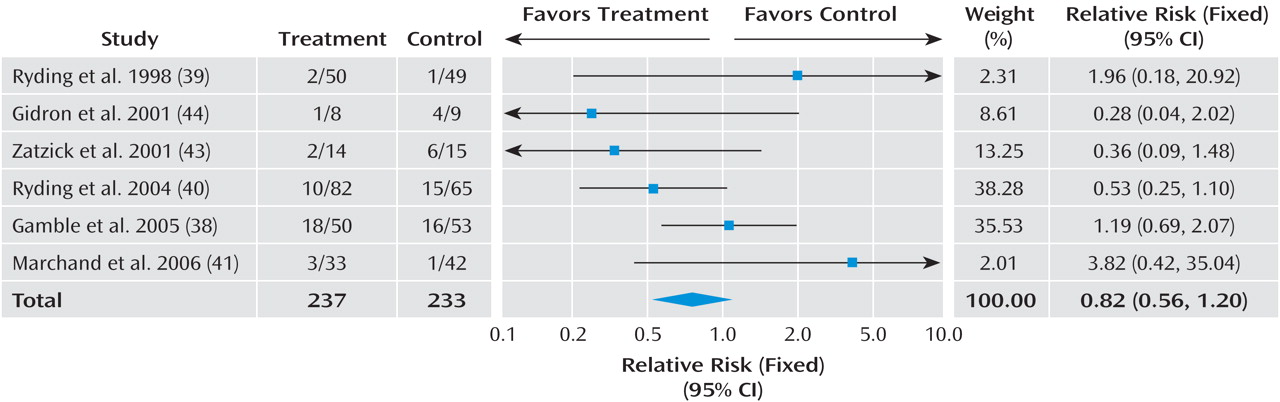

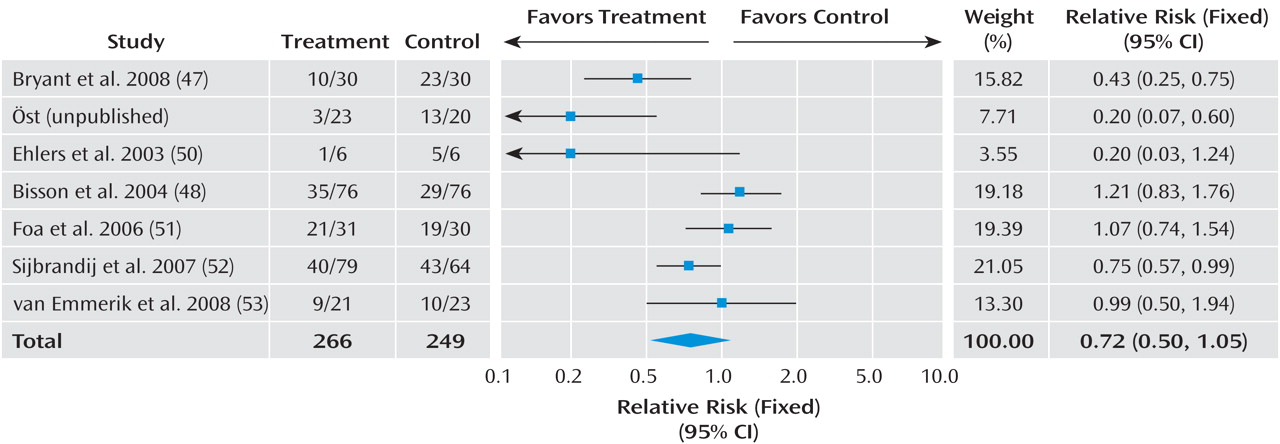

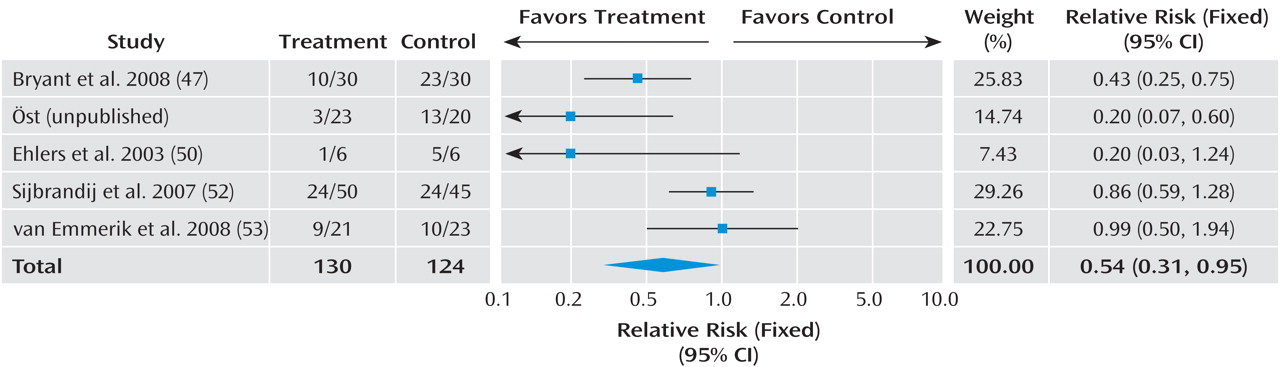

Given the differences between studies with respect to participants’ symptom severity and the interval between exposure to a traumatic event and commencement of the intervention, we separated the trials into three groups based on work previously conducted in this area

(16) : studies that offered an intervention to any individual exposed to a traumatic event irrespective of their symptoms with the aim of preventing PTSD; studies providing interventions begun within 3 months with the aim of preventing PTSD or ongoing distress in individuals with traumatic stress symptoms; and studies providing interventions begun within 3 months with the aim of preventing PTSD or ongoing distress in individuals with acute stress disorder or acute PTSD.

In order to combine information from several studies, all interventions offered to any individual exposed to a traumatic event with the aim of preventing PTSD were considered together. The efficacy of trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) was considered in individuals with traumatic stress symptoms. Trauma-focused CBT was defined as any intervention that focused on the trauma using exposure to trauma memories and trauma reminders with or without cognitive therapy and other cognitive-behavioral techniques. The exposure-based therapy with anxiety management

(30) and exposure-based therapy with hypnosis

(31) arms in two studies were combined with the exposure therapy arm to generate a single mean and standard deviation. The combined results were then compared with the waiting list arm to avoid double counting.

The data were analyzed for summary effects using Review Manager. Continuous outcomes were analyzed using weighted mean differences when all trials measured outcome on the same scale. When some trials measured outcomes on different scales, standardized mean differences were used, based on the assumption that all scales measure the same underlying symptom or condition. Relative risk was calculated for categorical outcome measures, and 95% confidence intervals were computed for all outcomes.

Available case analysis and intent-to-treat analysis with imputation using the last-observation-carried-forward method were performed when enough information was available. In cases where the information presented in the paper was inadequate to perform these analyses, further information was requested from the lead author.

Heterogeneity between studies was assessed by observing the I

2 test of heterogeneity, which measures the percentage of variation that is not due to chance

(32) . An I

2 of less than 30% was taken to indicate mild heterogeneity, and a fixed-effects model was used. When the I

2 was 30% or greater, a random-effects model was used. A visual inspection of the forest plots was used as a test of the robustness of these findings.