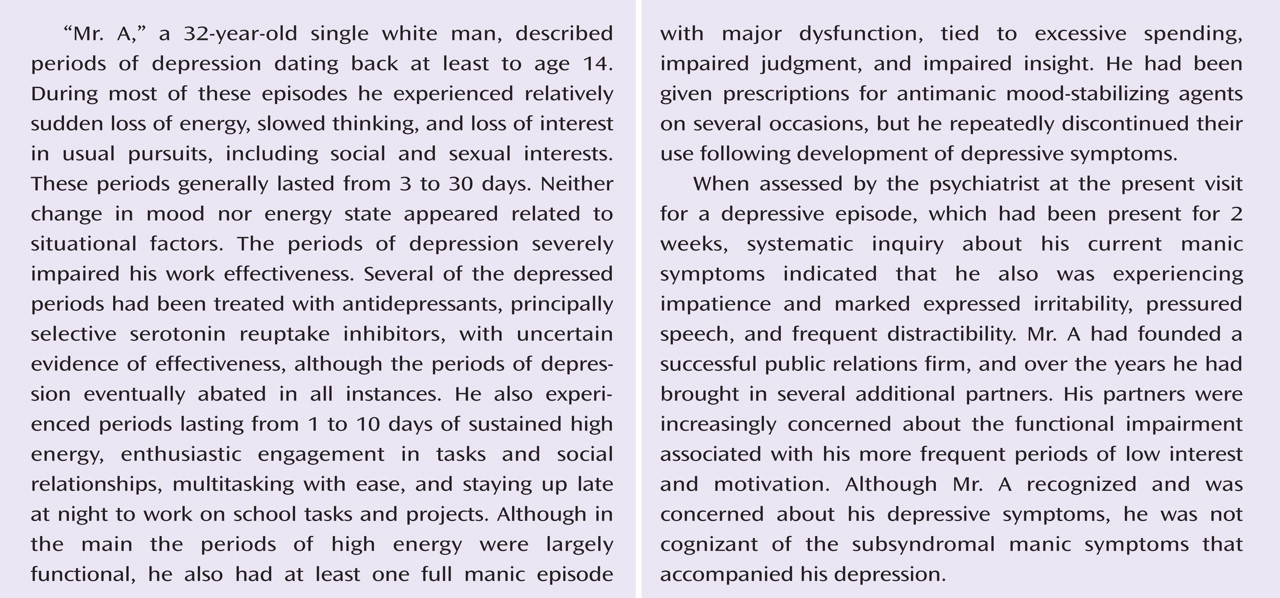

The presentation of individuals with bipolar disorder frequently includes depressive features that are mistaken for unipolar depression

(1) . Differentiating bipolar from unipolar depression holds pragmatic importance since the former appears much less likely than the latter to remit with traditional antidepressants

(2), and it responds no better to the combination of mood stabilizers plus antidepressants than to mood-stabilizing agents, such as lithium or divalproex, alone

(3 –

6) . Qualitative distinctions between bipolar and unipolar depression have traditionally focused on profiles of depressive symptoms, such as more frequent reversed neurovegetative signs in bipolar than unipolar depression

(7) . Less attention has been paid to the frequency and recognition of manic or hypomanic features that may arise in conjunction with bipolar depressive episodes, a nosologic construct of historical importance

(8) that was reintroduced to the modern literature by Koukopoulos and colleagues

(9 –

11) .

Subsyndromal mania and hypomania denote the presence of too few manic or hypomanic symptoms to meet the DSM-IV-TR criteria for a full manic or hypomanic syndrome. Subsyndromal mania that accompanies an episode of bipolar depression increases the propensity for mood destabilization following antidepressant exposure

(6), but little is known about the frequency, nature, and extent of concomitant mania symptoms arising in conjunction with bipolar depressive episodes. Mixed affective features hasten the time until syndromal relapse

(12) and also may confer heightened risk for recurrent suicidal features

(13) . Clarifying the nature of pure versus mixed bipolar depression bears not only on prognostic assessment and pharmacotherapy decisions but, moreover, on nosologic implications for DSM-V.

DSM-IV narrowly defines a mixed episode on the basis of the simultaneous presence of a full manic and full depressive syndrome for at least 1 week, solely for patients with bipolar I disorder. By contrast, ICD-10

(14) characterizes “mixed mania” on the basis of “either a mixture or a rapid alternation (i.e., within a few hours) of hypomanic, manic, and depressive symptoms,” with prominence of both manic and depressive symptoms for at least 2 weeks during a given episode. Suppes et al.

(15) studied simultaneous hypomanic and depressive features (“mixed hypomania”), operationally defined on the basis of thresholds on the severity scales of the Young Mania Rating Scale

(16) and Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology—Clinician-Rated Version

(17), and noted concomitant depressive features in one-half to two-thirds of patients—most often arising in women—with mild or moderate hypomania. Other investigators have proposed syndromes such as “mixed depression” or “depressive mixed states,” defined by the presence of three or more mania symptoms during bipolar II depressive episodes

(18) . Empirical efforts to validate such constructs have been scarce and often retrospective in study design

(19,

20) .

The goal of the present study was to estimate the frequency and clinical correlates of mania symptoms during depressive episodes in a large, well-characterized cohort of individuals with bipolar disorder. We hypothesized that concomitant mania symptoms would be more common than rare among bipolar disorder patients during full depressive episodes and that such mixed presentations would be associated with more complex elements of psychopathology, such as comorbid substance abuse, psychosis, rapid cycling, greater illness severity, and poorer psychosocial functioning than seen in pure bipolar depression.

Method

Participants

The study participants were 1,380 individuals with bipolar I (N=401) or II (N=979) disorder who met the DSM-IV criteria for a major depressive episode at the time of entry into the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD), a 22-site study sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) to examine clinical phenomenology, longitudinal course, and treatment effectiveness in people with bipolar disorder

(5,

6,

12,

21,

22) . DSM-IV diagnoses of bipolar I or II disorder were made at the time of study entry by a doctoral- or master’s-level clinician using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI Plus Version 5.0)

(23) . Clinical history, illness characteristics, and affective or psychotic symptoms were evaluated at study entry by using the Affective Disorders Evaluation

(21), a comprehensive intake assessment instrument that incorporates a modified version of the mood and psychosis modules from the Structured Interview for DSM-IV (SCID). Severity of depressive and manic symptoms was further rated by using the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale

(24) and the Young Mania Rating Scale

(16), respectively, at intake.

As described in detail elsewhere

(22), the STEP-BD subjects were ages 15 and older and were drawn from both academic and nonacademic treatment settings. The STEP-BD sites were U.S.-based hospitals or clinics that had existing specialty programs caring for large numbers of individuals with bipolar disorder. Sites were chosen on the basis of geographic and demographic diversity, as well as experience in conducting clinical research in bipolar disorder. Site personnel underwent training and certification in administering the primary clinical instruments and outcome measures, as well as training in evidence-based pharmacotherapies for bipolar disorder. STEP-BD purposefully employed broad inclusion criteria in an effort to enroll patients who were representative of individuals with bipolar disorder from across the United States. The patients in STEP-BD were not selected for treatment resistance or atypical demographic features.

Assessments

The DSM-IV criteria for an affective episode (i.e., a period of abnormal mood elevation, irritability, or depressed mood) at study entry were assessed from the Affective Disorders Evaluation, along with associated DSM-IV manic and depressive symptoms. The latter were identified on the basis of their achievement of definite DSM-IV threshold presence with at least moderate severity (a score on the Affective Disorders Evaluation of 1 or higher), as contrasted with ratings of either absence (i.e., normalcy; score of 0) or else mild presence and DSM-IV subthreshold intensity (score of 0.5). Interrater reliability among the STEP-BD physicians for rating associated DSM-IV manic and depressive symptoms was high (intraclass correlation coefficients, 0.83 to 0.99).

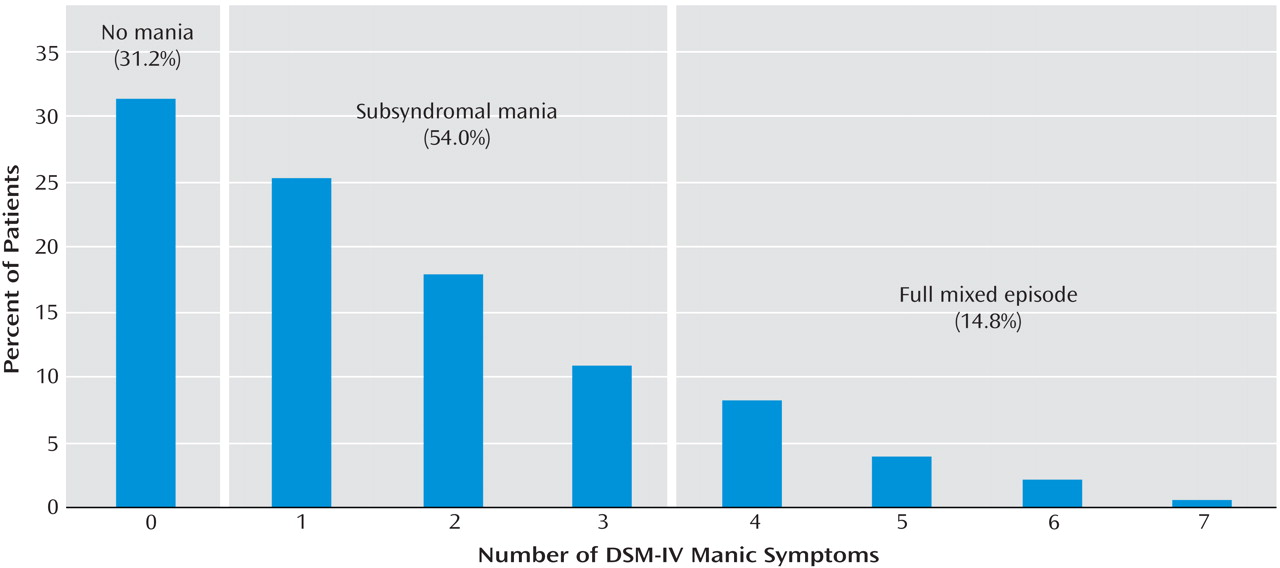

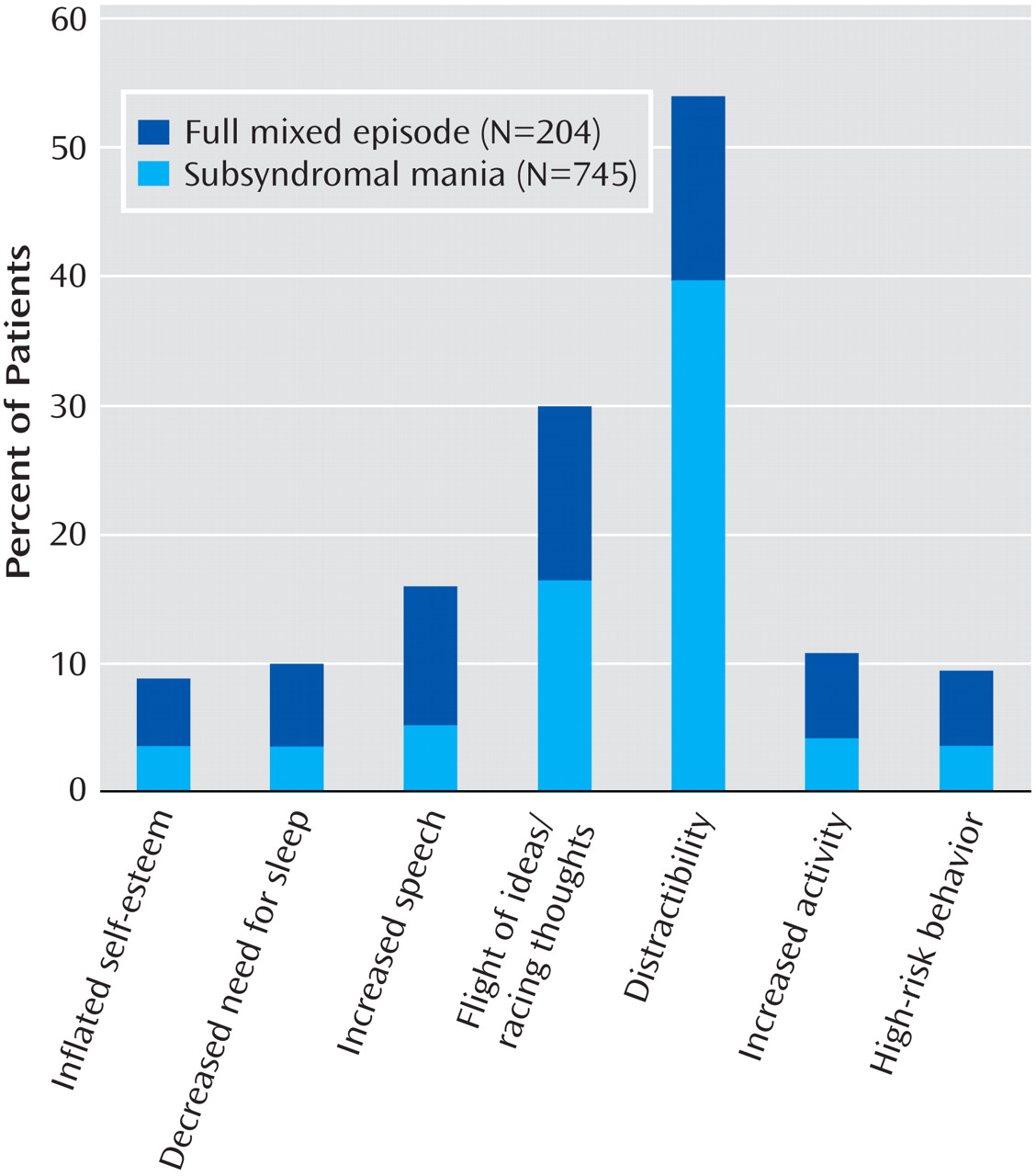

The presence and severity of irritable mood and or depressed mood in the preceding 2 weeks were each measured from the Affective Disorders Evaluation by using a 5-point scale for each mood state, on which “none” was rated as 0, “mild” as 1, “moderate” as 2, “marked” as 3, and “severe” as 4. Scores on the Affective Disorders Evaluation also were used to rate the presence of DSM-IV symptoms associated with mania, i.e., inflated self-esteem/grandiosity, decreased need for sleep, pressured speech, flight of ideas/racing thoughts, distractibility, increased goal-directed activity or psychomotor agitation, and engagement in high-risk behaviors. Three categorical study groups were identified and served as independent variables in subsequent analyses, on the basis of the presence of a full depressive episode plus 1) no manic symptoms, 2) subsyndromal mania (i.e., one to three definite mania symptoms), or 3) a full mixed episode (i.e., four or more definite mania symptoms).

Pharmacotherapies and psychotherapies received at study entry (i.e., prior to joining the STEP-BD study) were recorded at the time the Affective Disorders Evaluation was administered. All subjects provided written, informed consent for study participation at each of the respective STEP-BD investigative sites. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at each individual STEP-BD institution and by the STEP-BD data safety monitoring board.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed by means of Stata 9.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Tex.).

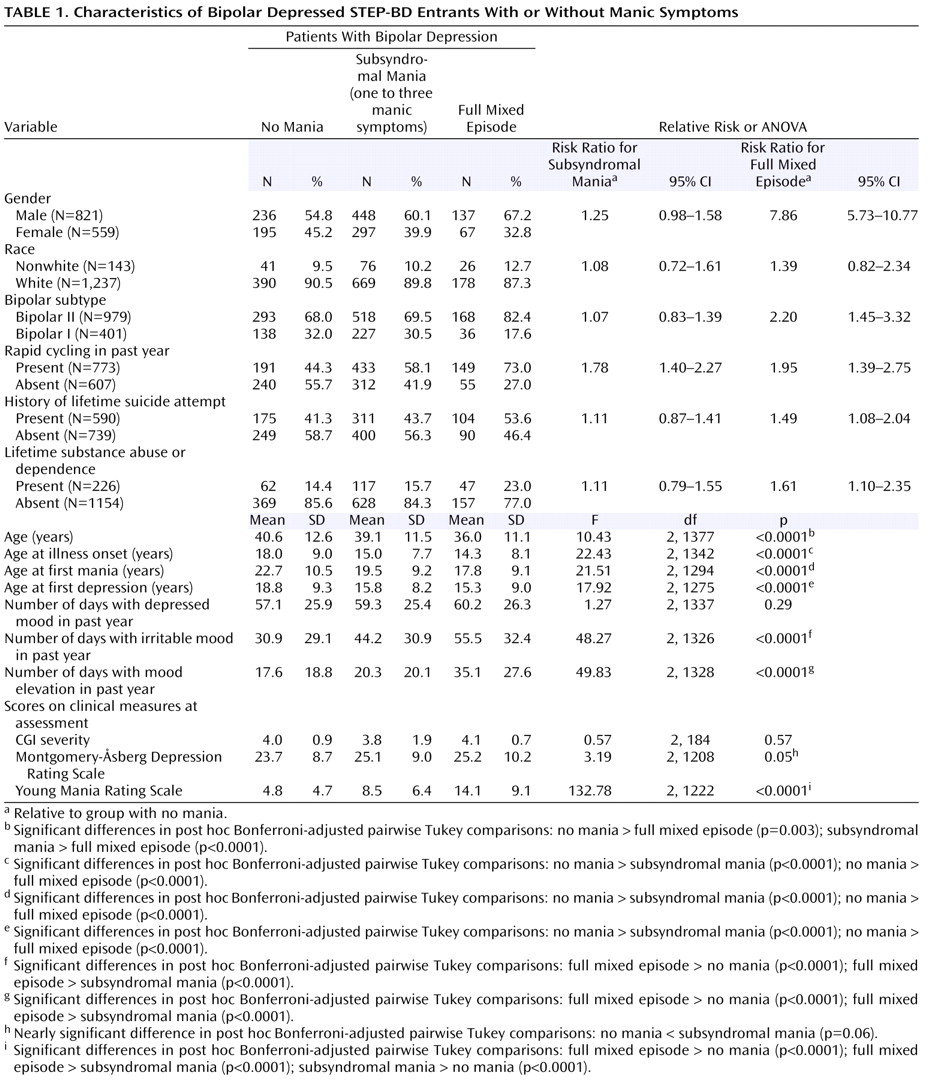

Comparisons of the three study groups were made by using chi-square analyses with Yates’s correction or Fisher’s exact tests (for dichotomous clinical dependent variables) or one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) with post hoc Tukey comparisons of mean scores for the continuous clinical dependent variables noted in

Table 1 . All statistical tests were two-tailed. Because of the exploratory, hypothesis-generating nature of the study, nominal p values are reported without correction for multiple comparisons.

Discussion

First recognized by Kraepelin

(8), mixed states are known to be associated with poorer response to various forms of treatment and a poorer overall illness prognosis

(25) . Reported prevalence rates of mixed states among bipolar patients with syndromal mania or hypomania have varied from 50% to 70%

(25), in part depending on whether an inclusive or restrictive approach was used to define the syndrome. DSM-IV-TR employs restrictive criteria for classifying mixed episodes, specifying that an individual must meet full syndromal criteria for both a major depressive episode and a manic episode. Using this approach, we found that only 14.8% of 1,380 consecutively assessed bipolar patients experiencing a major depressive episode also met criteria for mania. However, slightly more than one-half of the bipolar patients with syndromal depression had concomitant subsyndromal features of mania. By current DSM-IV-TR criteria, these individuals would be classified as having purely depressed rather than mixed phases of illness. Yet, the subsyndromally mixed subjects in the present study differed from those with pure bipolar depressive episodes on a wide range of clinically relevant variables.

Results from this large study group indicate that manic symptoms, to varying degrees, are present in a substantial number of bipolar I (30%) and bipolar II (71%) patients experiencing a depressive episode. Distractibility, racing thoughts/flight of ideas, and agitation were the most frequently identified manic symptoms. In addition, irritable mood was frequent in general, but particularly so when mixed mania features accompanied bipolar depression. Since irritability has previously been demonstrated to occur often in both unipolar and bipolar depression

(26,

27), it likely does not hold pathognomonic value for differentiating the polarity of affective episodes in patients with bipolar illness. It is also noteworthy that the specific manic symptoms with the highest frequency in bipolar patients in depressed episodes (distractibility, flight of ideas/racing thoughts, and psychomotor agitation) do not include either elation or grandiosity. This suggests that the DSM-IV-TR “B” criteria for mania may, unintentionally, serve to reduce recognition of manic symptoms in bipolar depressed patients.

Most commonly, clinicians organize information gathering around their patients’ self-report of the current or most recent mood state (i.e., the presenting chief complaint) rather than assessing all of the symptoms of depression and mania in every patient at every visit. The present findings indicate that about one-half of people seeking treatment for bipolar depression have concomitant signs of mania or hypomania that fall below the DSM-IV-TR threshold for a mixed episode. Our findings indicate that patients presenting in such subsyndromal mixed states are much more similar to those who meet the full DSM-IV-TR criteria for mixed episodes and differ substantially from those with pure bipolar depressive episodes. These differences have important clinical implications. Specifically, when compared to pure bipolar depression, subsyndromal mixed states are associated with greater lifetime illness severity, particularly more extensive suicide attempts and a greater frequency of historical rapid cycling. These data demonstrate the clinical importance of assessing patients with bipolar disorder for current symptoms of both poles of the illness regardless of patients’ self-reported current mood state.

Our observation of prominent mania symptoms in about two-thirds of syndromally depressed bipolar patients is similar to the frequency of mixed depression identified by Benazzi

(19) among 389 bipolar II depressed patients. That study, similar to the current one, also found a significantly earlier age at onset of bipolar disorder among subjects with mixed than nonmixed depression, consistent with mixed depression being a nosologically distinct entity from pure bipolar depression. The greater frequency of mixed depressive features among men than women in the current study is at variance with gender differences reported by Suppes and colleagues

(15), who identified a greater propensity for mixed hypomania in women than men with bipolar II disorder. However, that study compared the predominance of depressed versus elevated mood during full

hypomanic episodes that arose over a 7-year follow-up period, rather than in patients during a full

depressive episode. While other phenomenologic studies have pointed to a higher prevalence of mixed (as opposed to euphoric) mania in women than men

(28,

29), to our knowledge neither gender nor other patient characteristics have distinguished bipolar disorder patients with and without manic symptoms during a full depressive syndrome. Prior work has reported a comparable number of lifetime depressive episodes among women versus men with bipolar disorder

(30), although less is known about the phenomenology of depression in men versus women with bipolar disorder. The present findings suggest that full depressive episodes are more likely to involve concomitant manic symptoms among bipolar men than bipolar women. Future efforts are needed to confirm these observed sex differences and the potential link between subsyndromal mixed symptoms and other male traits associated with affective illness, such as impulsivity and aggression

(31) .

The presence of psychomotor agitation, while nonspecific to mania versus depression, has long been a focus of debate in the distinction between mixed episodes and unipolar agitated depression, as defined by the Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC)

(32) . Maj and colleagues

(33) identified RDC agitated depression in about 20% of bipolar disorder subjects during a full depressive episode, noting that motor hyperactivity, pressured speech, or racing thoughts were evident in about one-quarter of the patients. A somewhat higher frequency (31.2%) of psychomotor agitation was observed in the present cohort of depressed bipolar subjects, lending further support to the concept that agitated depression in bipolar disorder patients likely falls within a continuum between pure depression and a full mixed episode. Although motor retardation and anergic features are frequently reported in bipolar depression

(34), the present findings, in conjunction with other data

(35), indicate that psychomotor agitation is also a frequent characteristic of bipolar depression. Using the RDC definition of agitated depression—i.e., a full depressive syndrome involving at least two symptoms from the constellation of 1) motor agitation, 2) psychic agitation or intense inner tension, and 3) racing or crowded thoughts

(32) —we observed racing thoughts and psychomotor agitation in 20%–30% of subjects, respectively. These two features were correlated to a moderate but highly significant degree, suggesting that a number of patients with bipolar mixed features in the present study group met at least some of the RDC criteria

(32) for agitated depression.

Notably, the higher risk for lifetime suicide attempts we observed among depressed bipolar patients with mixed than among those with pure depressed features is consistent with prior findings that suggest an especially increased risk for recurrent suicidal features in bipolar disorder patients with mixed affective presentations

(13) . Moreover, while prior suicide research has emphasized the importance of depression as a driving factor contributing to suicide risk in patients with bipolar disorder, the current findings suggest the possibility that it is not only depression, but the superimposition of mania features (at even a subthreshold level) during bipolar depression that may denote a bipolar subgroup with an increased lifetime potential for suicide attempts. This hypothesis requires further investigation in prospective studies of longitudinal suicide risk in patients with bipolar disorder.

The limitations of the present study include the ascertainment of DSM-IV-TR mania symptoms and severity by means of the Affective Disorders Evaluation and the Young Mania Rating Scale; a more extensive symptom battery would have included symptoms now understood to be characteristic of manic states (i.e., impulsivity, affective lability, risky behaviors

[35] ). The present study intentionally focused on individual affective symptoms rather than the DSM-IV entity of a mixed episode, limiting the inferences one can draw about mania symptoms among patients with frank mixed episodes. The study group participants were predominantly white, were diagnosed more often with bipolar II than bipolar I disorder, had a relatively high rate of prior suicide attempts, and were willing to participate in treatment-based research; generalizability to broader populations of individuals with bipolar disorder may be limited by characteristics such as these. The cross-sectional nature of the present study also did not provide an opportunity to determine the longitudinal stability of mixed features in recurrences of depression in bipolar disorder patients, although prior studies suggest a high probability for depressive mixed states to recur

(36) . Data from subsequent prospective follow-up of the STEP-BD cohort may help to shed further light on this issue.

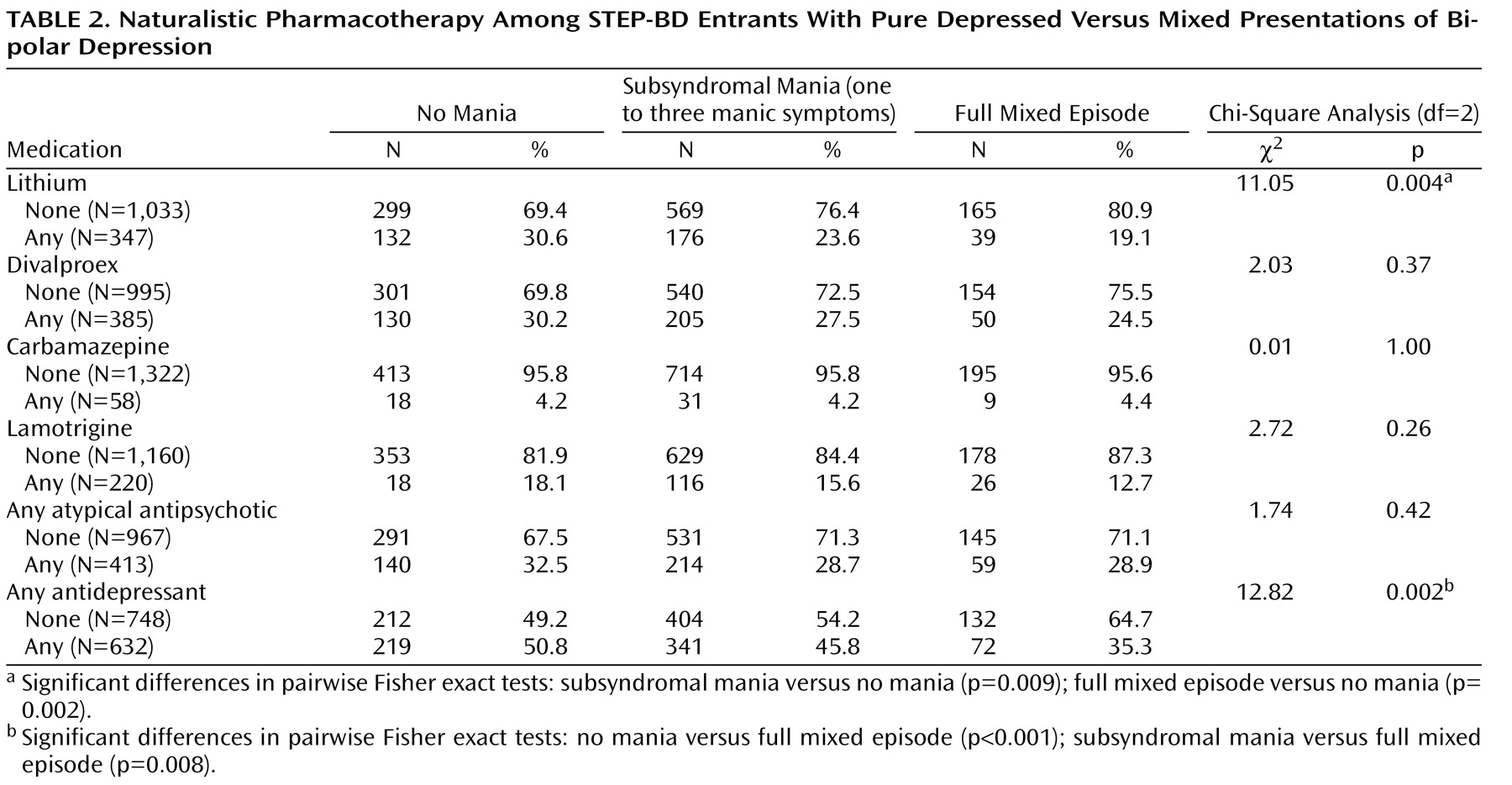

Since the ascertainment of depression occurred in a group of individuals who, for the most part, had received some form of treatment before entry into STEP, one cannot rule out the possibility that treatments received for the current episode contributed to the results. Because subjects who were taking antidepressants at the time of study entry had fewer (rather than more) threshold-level symptoms of mania as compared to those not taking antidepressants, antidepressant pharmacotherapy would not appear to have been a major factor contributing to symptom presentations at study entry. The data on naturalistic pharmacotherapy at the time of study entry suggest that practitioners may be less inclined to use either lithium or antidepressants for bipolar patients with mixed features, a possibility consonant with recommendations made in current practice guidelines that advise against the use of antidepressants in mixed episodes

(37) and favoring other mood-stabilizing agents over lithium

(38) when manic and depressive symptoms co-occur.

In summary, the present findings indicate that a majority of patients with bipolar disorder with a full depressive episode have clinically relevant manic symptoms. Bipolar mixed depression represents a clinically relevant entity with features that differ fundamentally from those of pure bipolar depression. Future studies are needed to compare treatment response, recovery rates, and illness course among these subtypes in order to further consolidate evidence for their nosologic validity.