Studies have suggested that 12%–25% of all pregnant women display some signs of depression

(1,

2) and 2%–13% are treated with antidepressants

(3,

4) . The most commonly used antidepressants among pregnant women are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs [

3,

4 ]). Antidepressants can control mood effectively and reduce the risks of serious consequences associated with untreated depression for both the mother and her offspring

(5,

6) . However, the use of antidepressants during pregnancy could be potentially associated with adverse effects on the fetus. Although findings have not been consistent for some outcomes

(7 –

12), first trimester exposure to certain SSRIs has been associated with specific birth defects

(13 –

16), and SSRI use during late pregnancy has been associated with pulmonary hypertension of the newborn

(17), prematurity

(18 –

21), low birth weight

(20,

21), small weight for gestational age

(22), and various other neonatal complications

(18 –

20,

23) . Very few studies have focused on the potential medical and obstetrical adverse effects of antidepressants on the mothers themselves. A leading cause of morbidity and mortality during pregnancy is preeclampsia, clinically recognized by gestational hypertension and proteinuria

(24,

25) . It has been suggested that psychological conditions, such as stress

(26), anxiety, and depression

(27,

28), may trigger the pathogenic vascular processes that lead to this condition. Serotonin may play an important role in the etiology of preeclampsia through its vascular and hemostatic effects

(29), and SSRIs have been shown to affect circulating serotonin levels

(30) . The few studies that have suggested an elevated risk of preeclampsia among pregnant women with depression did not assess the potential independent effect of medications

(27,

28) . If an association between pregnant women with depression and an increased risk for preeclampsia exists, it would still be unclear whether this association is a result of biological or behavioral factors intrinsic to women with mood disorders, medications used to treat the disorders, or a combination of both. Women who are treated with medications for depression and are pregnant or planning a pregnancy often struggle, along with their doctors, with the decision about treatment options, and a critical clinical question is whether to continue or discontinue antidepressant treatment during pregnancy. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the risk of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia associated with the continuation and discontinuation of antidepressant use beyond the first trimester.

Results

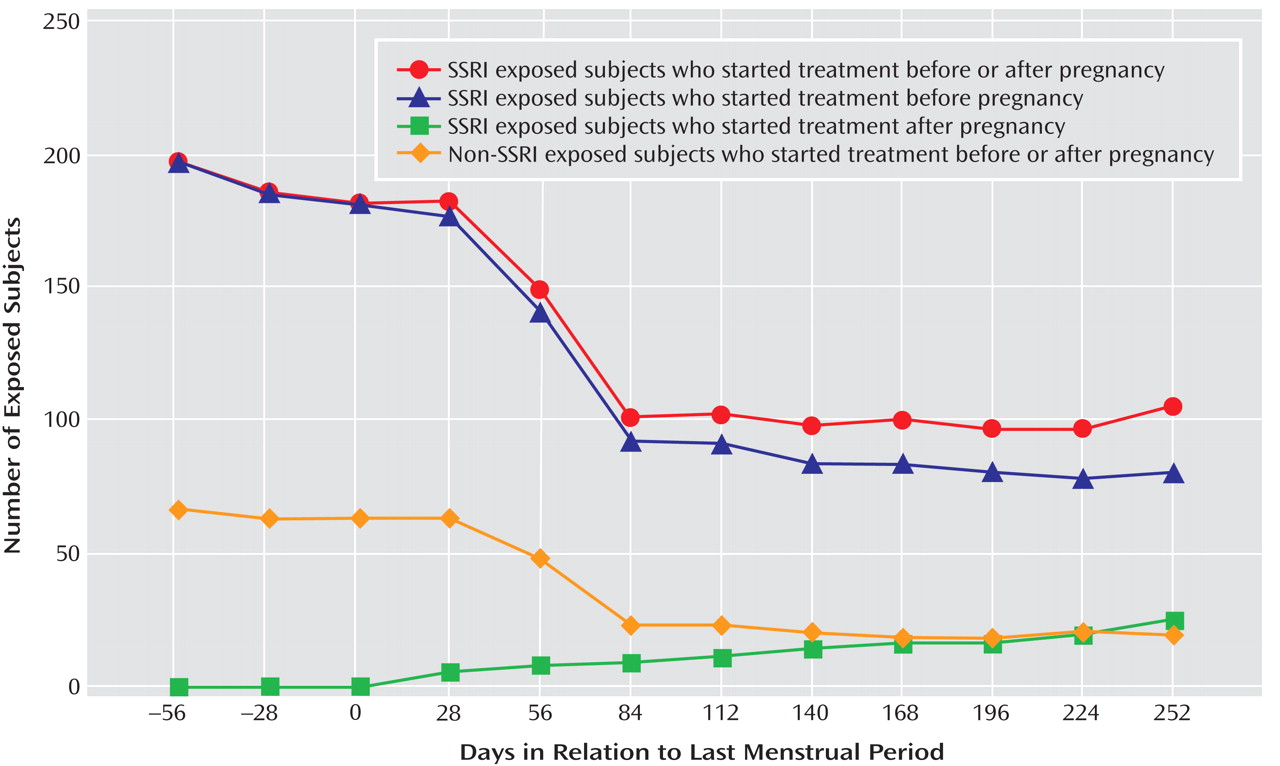

Of the 5,731 women without pregestational hypertension, 538 (9.4%) reported being diagnosed with gestational hypertension. Among these, 153 (28.4%) developed preeclampsia (2.7% of all subjects). A total of 199 women (3.5%) were being treated with SSRIs 2 months before conception (191 used these medications for mood disorders). Among this group of women, 107 discontinued SSRI treatment before the end of the first trimester, and 92 continued treatment beyond the first trimester (

Figure 1 ). Most women maintained their exposure status during the later trimesters. However, twelve of the women (11.2%) who discontinued treatment restarted their treatment, and six women (6.5%) in the continuing treatment group discontinued treatment later in pregnancy.

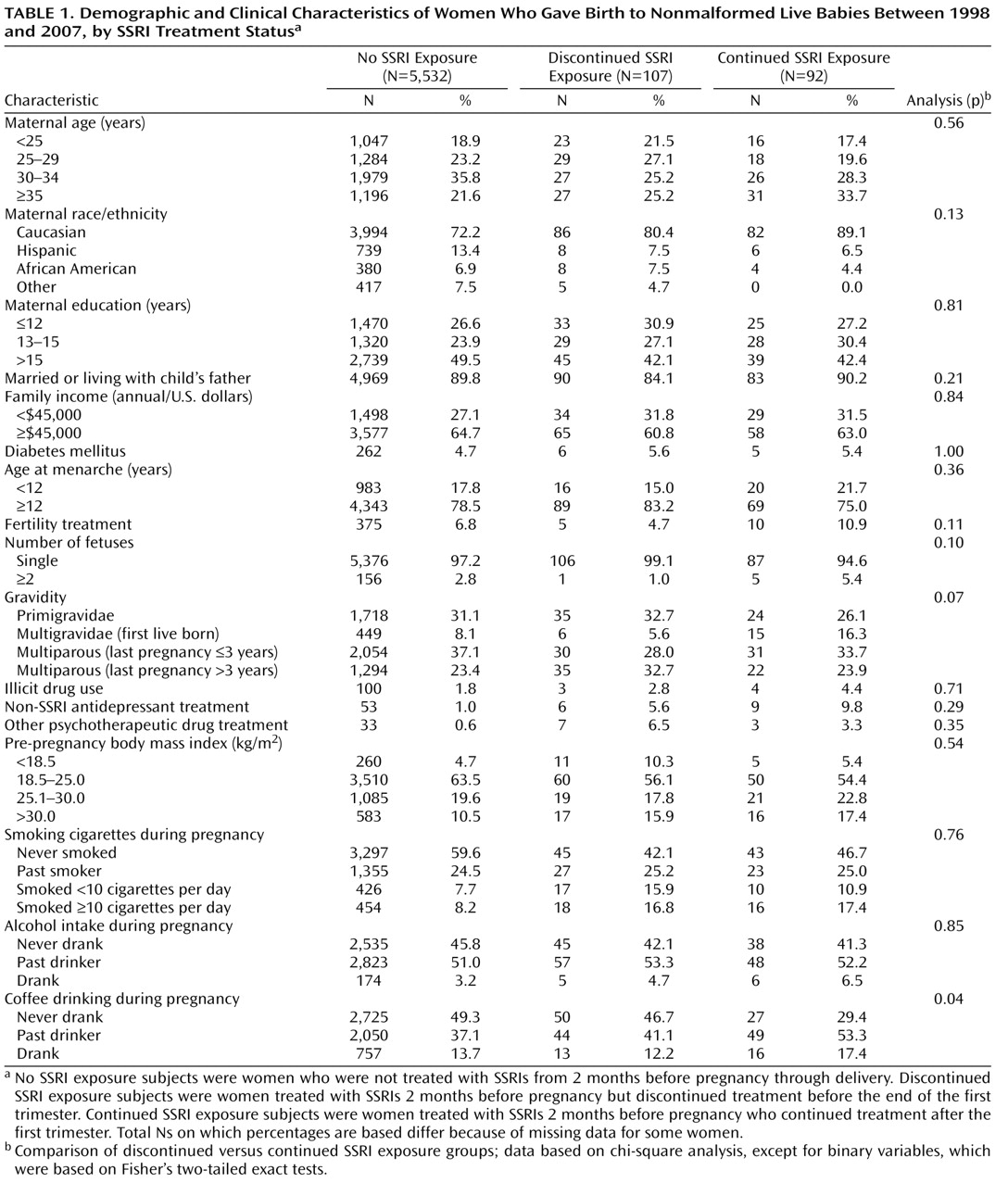

Maternal characteristics based on SSRI treatment status are shown in

Table 1 . Women who discontinued and continued treatment did not differ substantially in their baseline characteristics. The risk of gestational hypertension and/or preeclampsia was associated with the following variables: region, younger maternal age, Caucasian ethnic background, unmarried or not living with the child’s father, lower family income, younger age at menarche, cigarette smoking, diabetes mellitus, higher prepregnancy body mass index, multiple gestations (twins or more), primigravidae, and history of fertility treatment. These variables were included in our final models.

Sixty-eight women were being treated with non-SSRI antidepressants 2 months before pregnancy (16 women were treated with serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors [SNRIs]). Among this group of women, 13 (19.1% [three women were treated with SNRIs]) developed gestational hypertension and four (5.9% [one woman was treated with SNRIs]) developed preeclampsia. Compared with women who did not receive these antidepressants, the adjusted relative risk for women who were treated with non-SSRI antidepressants immediately before or during pregnancy was 1.58 (95% CI=0.90–2.80) for gestational hypertension and 1.55 (95% CI=0.55–4.38) for preeclampsia. As a result of these small numbers, non-SSRI antidepressant use was not analyzed further, except as a potential confounder.

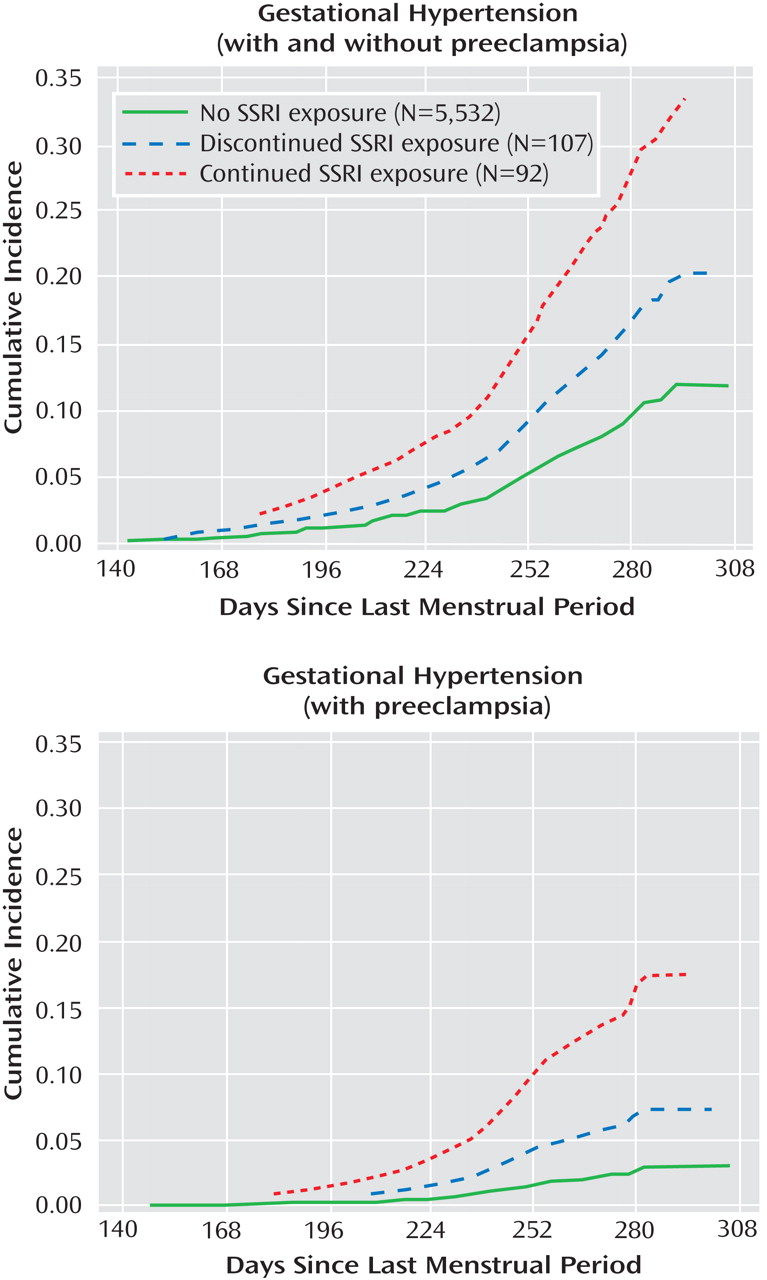

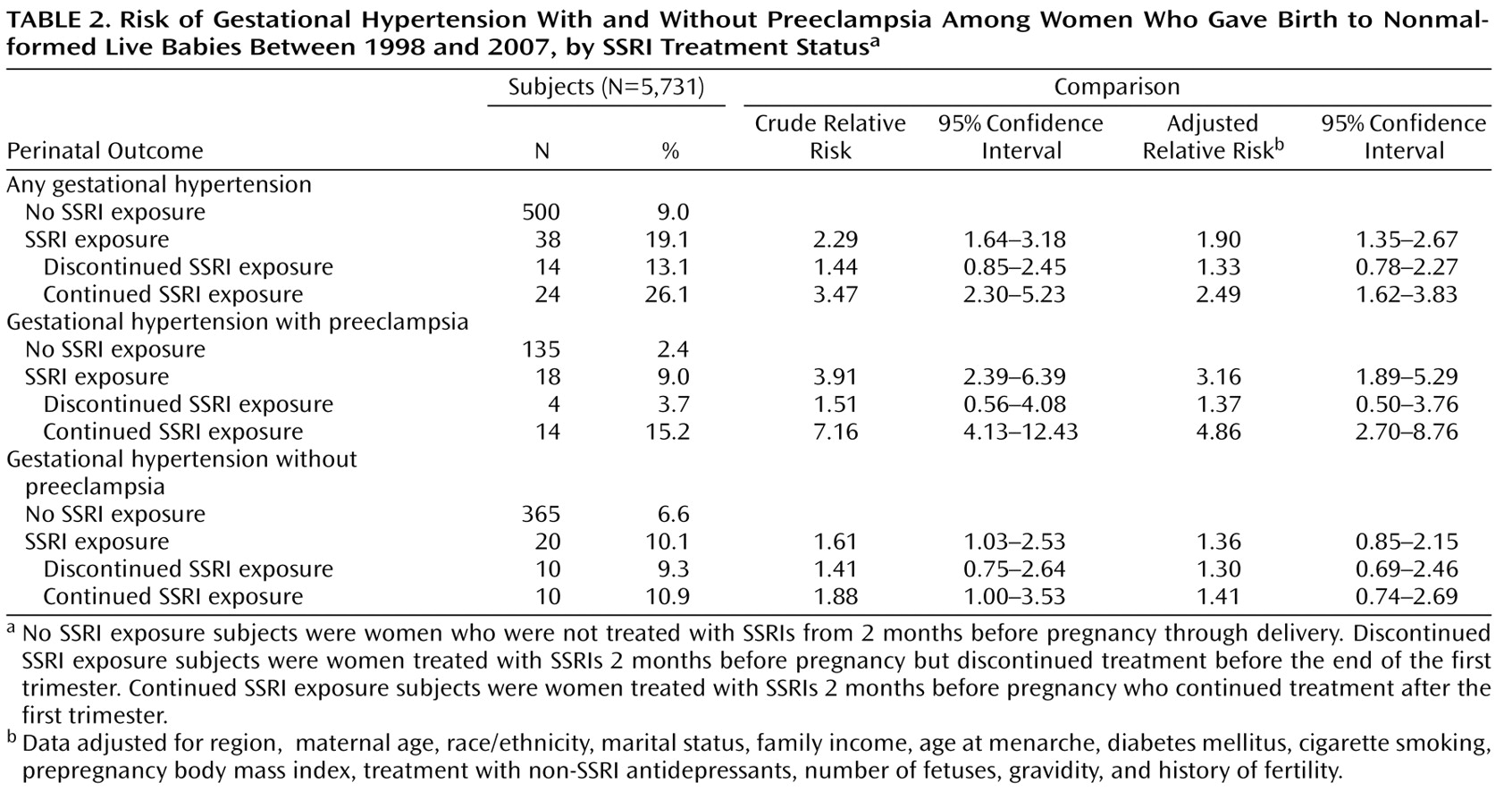

Figure 2 shows the cumulative occurrences of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia according to SSRI exposure status. Women who were treated with SSRIs had a higher risk for gestational hypertension compared with women who were not exposed to SSRIs. This risk was greater for women who continued treatment relative to women who discontinued treatment (

Table 2 ). The increased risk for gestational hypertension observed among women who continued treatment appeared to be largely attributable to preeclampsia, although there was also an indication of an elevated risk for gestational hypertension without preeclampsia. The results were similar when women who discontinued treatment before the end of the first trimester and did not restart their treatment were compared with women who continued treatment after the first trimester and did not discontinue their treatment during later trimesters. Relative risks did not vary greatly by gravidity or smoking status. In addition, restricting our analyses to singleton births or evaluating women who were exposed to SSRIs only (and not to non-SSRI antidepressants concomitantly) did not significantly alter the results. We did not have the power to evaluate specific SSRIs. There were 146 and 35 early-onset cases of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia, respectively. Compared with women who did not receive treatment with SSRIs, the relative risks among women who continued and discontinued treatment with SSRIs were similar for early- and late-onset gestational hypertension. However, when we compared women who continued treatment with women who did not receive treatment, the relative risk for early onset preeclampsia among women who continued treatment was 16.4 (95% CI=6.2–43.7 [based on six cases among women who continued treatment]), and the relative risk for late-onset preeclampsia among women who continued treatment was 3.5 (95% CI=1.6–7.5 [based on eight cases among women who continued treatment]). There was no indication of violation of the proportional hazards assumption in any of the analyses.