Depression is the single most significant psychiatric risk factor for adolescent suicidal behavior. While antidepressants have been shown to be efficacious in the treatment of adolescent depression, one potentially serious effect of their use is an increased risk for spontaneously reported suicidal events

(1) . However, little is known about the predictors and clinical significance of these events, nor about the relationship of spontaneously reported events to those that are systematically assessed.

Contemporaneous with safety concerns, there has been both a decline in the prescription rate for antidepressants and a reversal of the decade-long decline in the adolescent suicide rate in the United States

(2,

3) . The identification of predictors of suicidal events in depressed patients could be helpful in providing informed consent, identifying those patients at highest risk, and for designing preventive interventions.

Predictors of suicidal events in treated, depressed samples include a past suicide attempt and high baseline levels of suicidal ideation, agitation, and anger

(4 –

6) . However, none of the above-noted studies have simultaneously examined the effects of both demographic and clinical predictor variables, treatment, and their interactions. Moreover, aside from an unpublished Food and Drug Administration report that suggests a tendency toward an increased risk of nonsuicidal self-injury with antidepressant medication versus placebo, the occurrence of nonsuicidal self-injury has not been examined in pediatric clinical trials

(7) .

Predictors of suicidal events, namely high levels of suicidal ideation or a recent suicide attempt are also common reasons for initiating antidepressant treatment in the community, and for excluding such patients from clinical trials

(8) . In order to be informative to community practice, we report on the predictors of suicidal and nonsuicidal self-injury adverse events in the Treatment of SSRI-Resistant Adolescent Depression (TORDIA) study, in which nearly 60% of participants who entered this clinical trial had clinically significant suicidal ideation and over one-third had a previous history of nonsuicidal self-injury

(9) . In TORDIA, depressed adolescents who did not respond to an adequate trial with an SSRI were randomly assigned, in a 2-by-2 balanced factorial design, to one of four groups: switch to another SSRI, switch to venlafaxine, switch to another SSRI plus cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), or switch to venlafaxine plus CBT. In the first 12 weeks, one-fifth of participants experienced a self-harm (either a suicidal or nonsuicidal self-injury) adverse event, but there were no differential treatment effects

(9) .

In this article, we examine the predictors and moderators of treatment effects on the occurrence of suicidal and nonsuicidal self-injury adverse events. Moreover, we capitalize on a natural experiment. During the first half of the study, participants were monitored for self-harm adverse events by spontaneous report, similar to previous studies

(1,

10) . However, in response to concerns raised by the FDA in 2003–04

(11), participants enrolled in the latter half of the recruitment period were monitored by systematic, proactive assessment of suicidal ideation and behavior and nonsuicidal self-injury, thus allowing for a comparison of the frequency and severity of suicidal events as assessed by spontaneous report and by systematic evaluation.

Results

Number and types of self-harm adverse events

There were 108 incidents of self-harm adverse events in 68 participants: 58 suicidal adverse events in 48 participants, and 50 nonsuicidal self-injury events in 31 participants, 11 of whom also had a suicidal adverse event. Of the 48 participants who experienced at least one suicidal adverse event, 17 made suicide attempts (asphyxiation [N=3], cutting or stabbing [N=6], or overdose [N=8]), but none completed suicide. There were 50 nonsuicidal adverse events in 31 participants. The most common methods were cutting (N=28), scratching (N=1), both (N=4), and burning (N=2). There were 26 serious self-harm adverse events, of which 24 were suicidal adverse events (92.3%).

Rate of Events Before and After Systematic Monitoring

More suicidal (20.9% versus 8.8%, χ 2 =9.18, df=1, p=0.002) and nonsuicidal self-injury adverse events (17.6% versus 2.2%, χ 2 =23.47, df=1, p<0.001) were detected after systematic monitoring, with no difference in the rate of serious suicidal or nonsuicidal self-injury adverse events (8.4% versus 7.3%, χ 2 =0.03, df=1, p=0.87). Suicide attempts tended to be more frequent with systematic monitoring (6.5% versus 3.9%, χ 2 =1.22, df=1, p=0.27). Time to onset for either type of event was earlier under conditions of systematic monitoring (median time 2 versus 5 weeks, χ 2 =8.41, df=1, p=0.004).

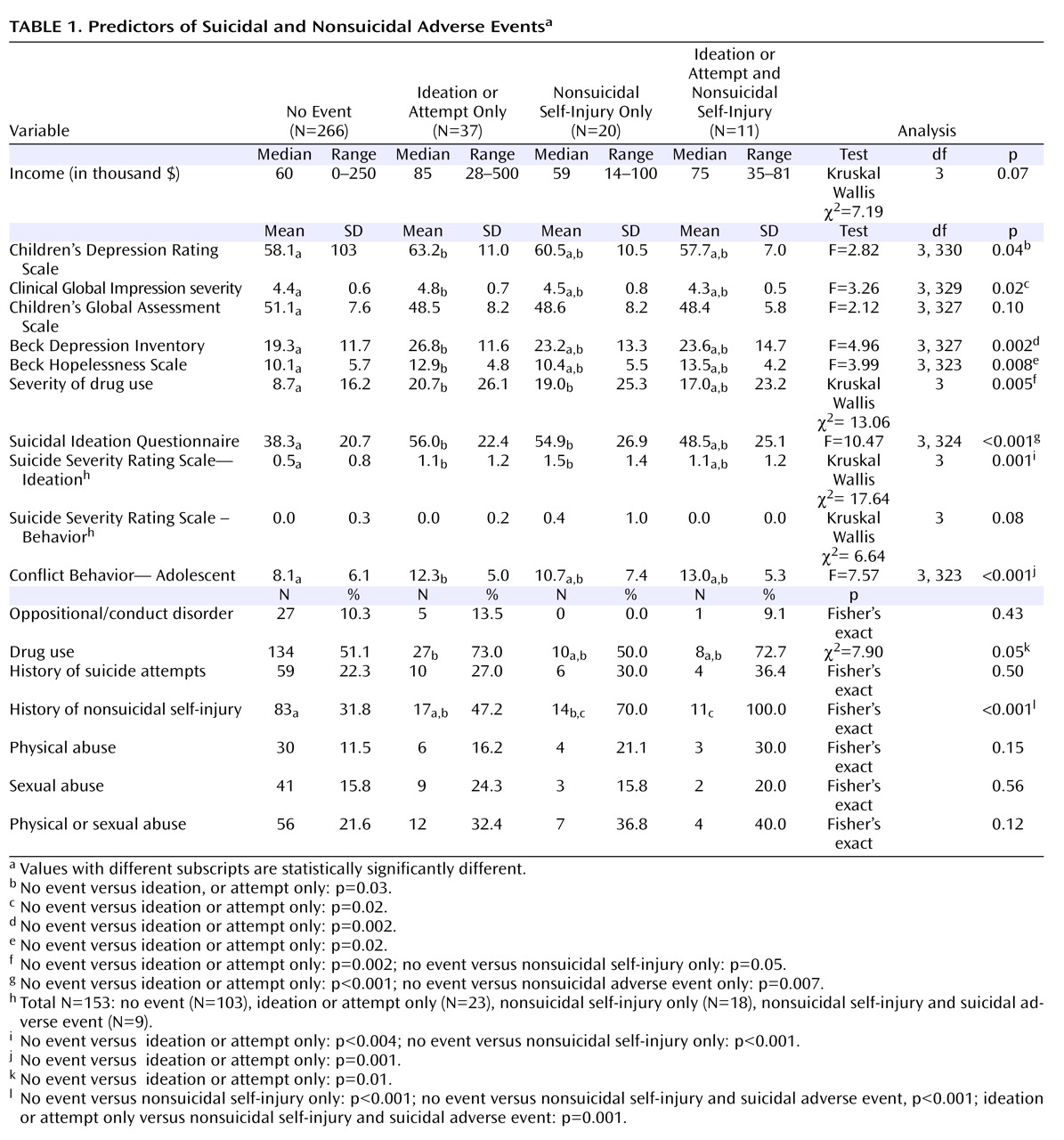

Characteristics of Those With Suicidal and Non-Suicidal Self-Injury Adverse Events

Baseline characteristics of those with no event, suicidal adverse events only, nonsuicidal self-injury only, or both were compared. There were overall differences among these four groups for most measures of clinical or symptomatic severity, adolescent reported family conflict, and history of nonsuicidal self-injury (see

Table 1 ). Pairwise contrasts showed significant differences between those with suicidal adverse events without nonsuicidal self-injury compared to those without events for severity of interview-rated and self-rated depression, hopelessness, drug use, suicidal ideation, and family conflict. The two groups with nonsuicidal self-injury events were each more likely to have had a history of nonsuicidal self-injury, compared to those with no events. Also, those with nonsuicidal self-injury only compared to those with no events had higher suicidal ideation (54.9 [26.9] versus 38.3 (20.7), t=2.64, df=19.6, p=0.02) and greater impairment from drug and alcohol use (19.0 [25.3] versus 8.7 [16.2], Mann-Whitney U=2017, p=0.05).

Baseline Predictors of Occurrence and Time to Suicidal Events

The median time to a suicidal adverse event was 3 weeks (interquartile range=5 weeks), whereas the median time to a suicidal serious suicidal or nonsuicidal self-injury adverse event was 5 weeks (interquartile range=5 weeks). Those who experienced multiple events were not different from those with a single event. Logistic regression identified self-rated suicidal ideation (odds ratio=1.02, 95% CI=1.01–1.04), family conflict (odds ratio=1.1, 95% CI=1.03–1.16), and drug or alcohol use (odds ratio=1.9, 95% CI=0.9–3.9) as the best predictors of suicidal adverse events study (Hosmer-Lemeshow χ 2 =11.75, df=8, p=0.16), with similar predictors for time to suicidal events using a backward stepwise Cox regression: suicidal ideation (z=2.99, p=0.003), family conflict (z=2.91, p=0.004), and drug and alcohol use (z=1.87, p=0.06).

Baseline Predictors of Onset and Time to Nonsuicial Self-Injury Events

Logistic regression identified a history of nonsuicidal self-injury (odds ratio=9.6, 95% CI=3.5-26.1) as the best single predictor of nonsuicidal self-injury events. The median time to a nonsuicidal self-injury event was 2 weeks (interquartile range=4 weeks), with the best predictor of time to event being a history of nonsuicidal self-injury (z=4.40, p<0.001).

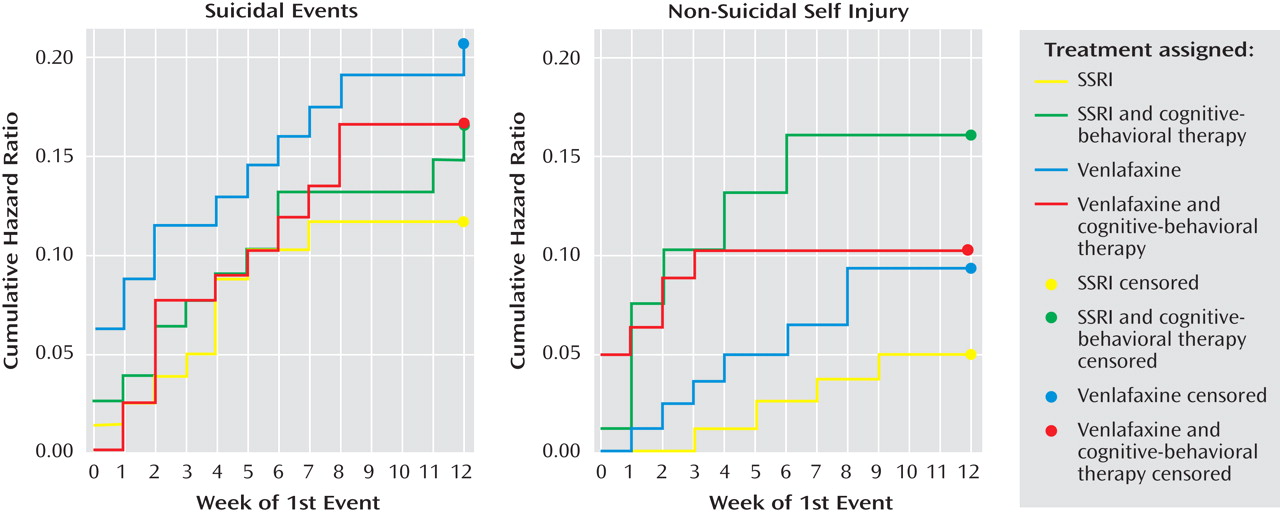

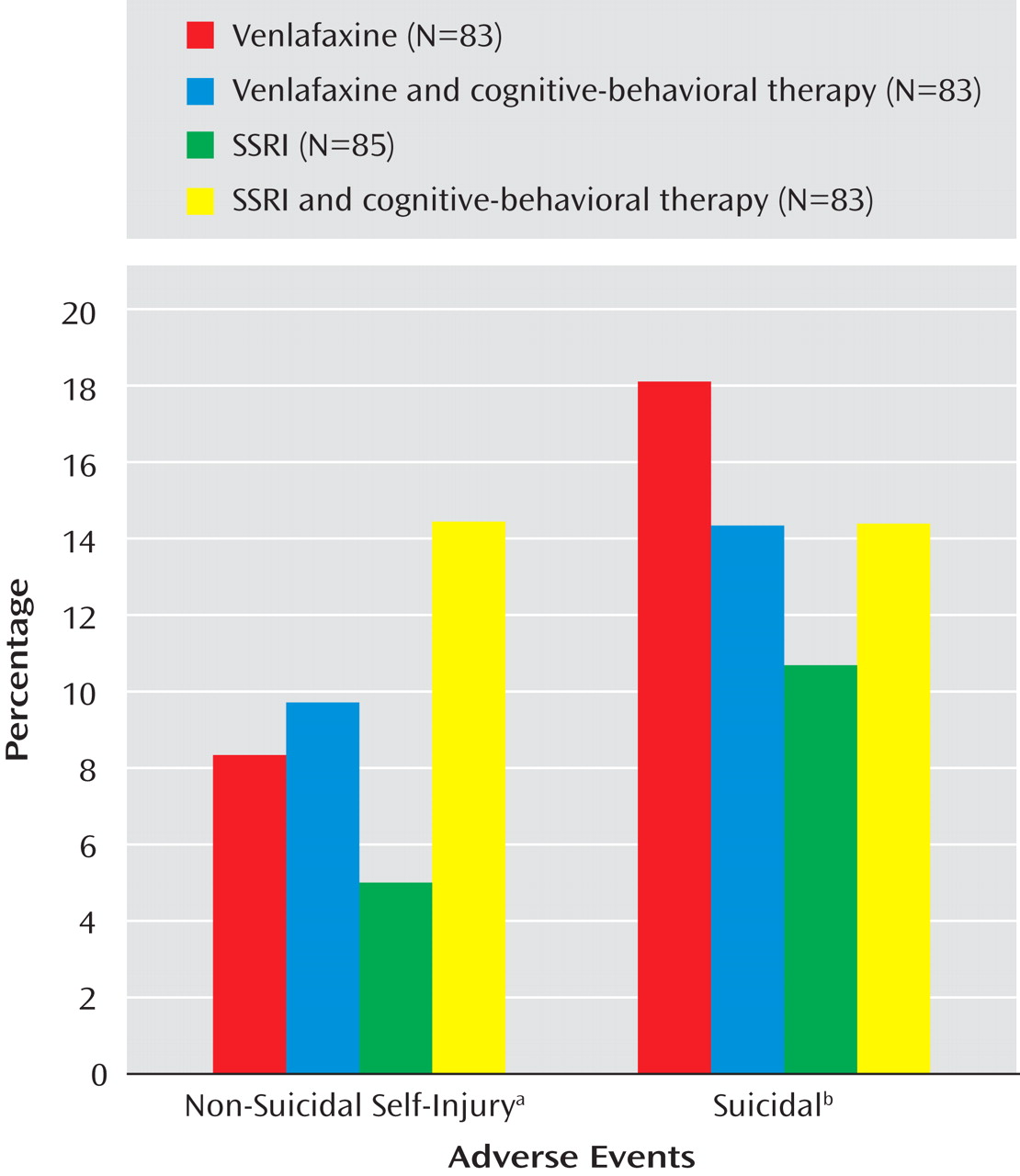

Impact of Treatment on Suicidal and Nonsuicidal Adverse Events

There were no statistically significant treatment effects with regard to the occurrence of suicidal or nonsuicidal self-injury events adverse events (see

Figure 1 ). There were no treatment effects for time to suicidal adverse events, but receipt of CBT was related to earlier onset of an nonsuicidal event (hazard ratio=3.3, z=2.05, p=0.04). (See

Figure 2 ). After controlling for a history of nonsuicidal event (hazard ratio=7.7, z=4.5, p<0.001), the relationship between CBT and time to nonsuicidal event was no longer significant (hazard ratio=2.0, z=1.81, p=0.07).

Only one of the above-noted baseline predictor variables was found to moderate treatment effects with respect to onset or time to either suicidal or nonsuicidal event adverse events. Cox regression, with all main effects and two-way interactions in the model showed a significant interaction between medication and suicidal ideation (z=3.10, p=0.002) with respect to occurrence of any self-harm adverse event, meaning that participants with higher than median baseline suicidal ideation (Suicide Ideation Questionnaire score ≥35) were more likely to experience a self-harm event if they were treated with venlafaxine than with an SSRI (37.2% versus 23.3%, χ 2 =3.83, df=1, p=0.05).

Relationship of Treatment Course, Treatment Response, and Occurrence of Suicidal Events

Participants with a suicidal adverse event had a lower rate of treatment completion (41.7% versus 73.8%, χ 2 =19.87, df=1, p<0.001), treatment response (defined as CGI improvement rating ≤2 and ≥50% decrease in CDRS-R from baseline; 27.1% versus 51.0%, χ 2 =9.46, df=1, p=0.002), and a tendency toward lower attendance at pharmacotherapy sessions (7.3 [2.3] versus 7.9 [2.2], t=1.87, df=332, p=0.06), but did not attend fewer CBT sessions (7.7 [3.4] versus 8.4 [3.6], t=0.93, df=164, p=0.35). There was no relationship between experience of a nonsuicidal event and rate of treatment completion rate (58.1% versus 70.3%, χ 2 =1.97, df=1, p=0.16), or with treatment response (35.5% versus 48.8%, χ 2 =2.01, df=1, p=0.16), number of pharmacotherapy (7.8 [1.8] versus 7.8 [2.3], t=0.48, df=332, p=0.96) or CBT sessions attended (7.8 [3.2] versus 8.4 [3.6], t=0.66, df=164, p=0.51).

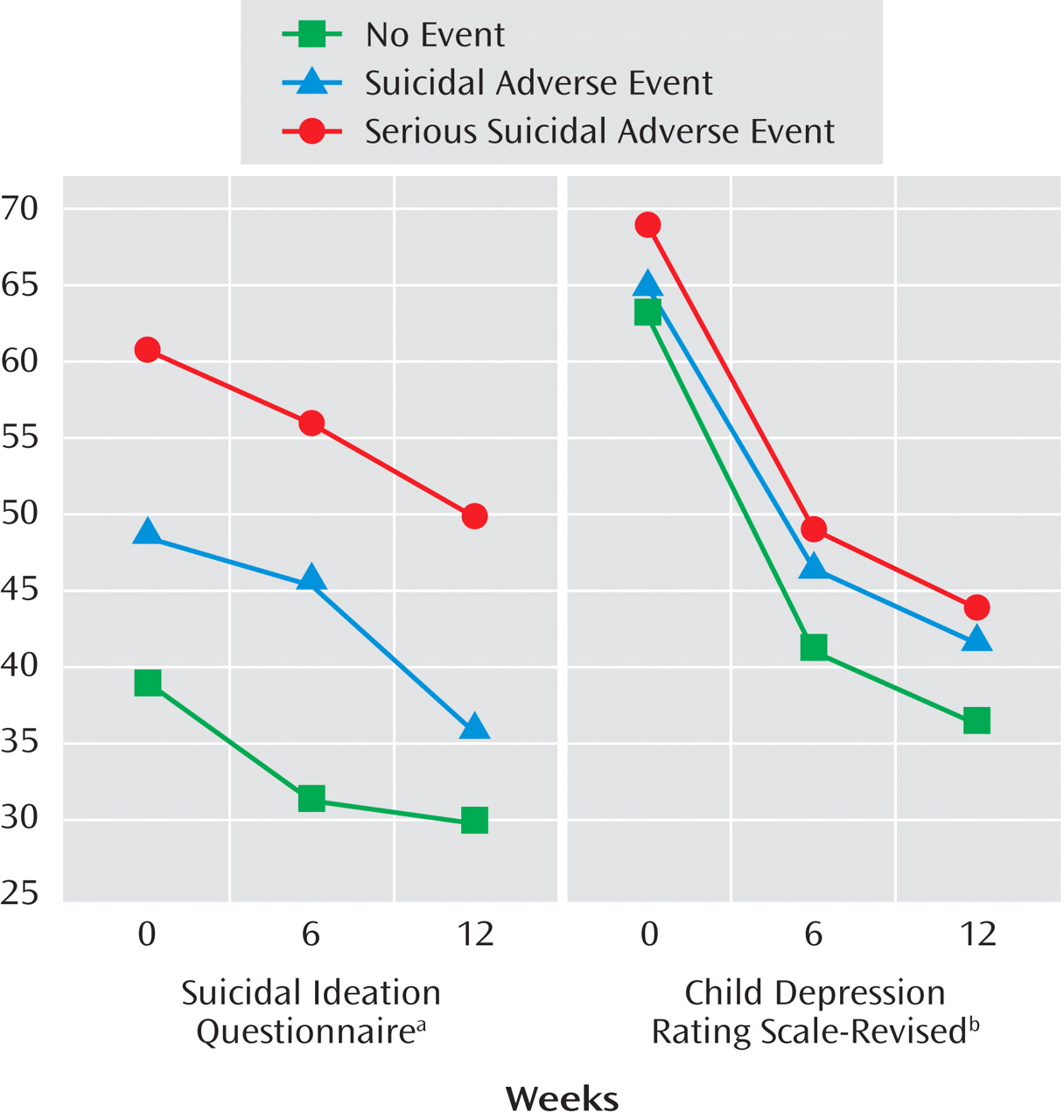

The trajectory of those who experienced a serious suicidal adverse event, a “non-serious” suicidal adverse event, and those who never experienced any suicidal events with respect to course on the Suicide Ideation Questionnaire and CDRS-R showed significant effects for time, event status (highest baseline symptoms associated with serious suicidal or nonsuicidal self-injury adverse event’s), but no event by time interaction, with similar findings for those with and without nonsuicidal adverse events (see

Figure 3 ).

Relationship of Adjunctive Treatment to Suicidal Adverse Events

There was no association between either adjunctive use of sleep medications or stimulants and suicidal events. Treatment with benzodiazepines was associated with suicidal adverse events (6 of 10 [60.0%] versus 42 of 324 (13.0%), Fisher’s exact test, p<0.001). The majority of benzodiazepine use took place at one site (8 of 10), but the relationship between benzodiazepine use and suicidal events persisted when the analyses were restricted to that site (4 of 8 [50.0%] versus 9 of 84 [10.7%], Fisher’s exact test, p=0.01). The use of a benzodiazepine was associated with a faster time to a suicidal event (z=3.27, p=0.001), even after control was added for baseline differences in self-rated ideation (z=2.18, p=0.03), family conflict (z=3.02, p=0.003), and drug or alcohol use (z=2.13, p=0.03).

Relationship of Adjunctive Treatment to Nonsuicidal Self-Injury

There was no association between the use of stimulants and nonsuicidal self-injury events. There was a much higher rate of nonsuicidal self-injury events in those treated with benzodiazepines (4 of 10 [40.0%] versus 27 of 324 [8.3%], Fisher’s exact test, p=0.009) and in those who received treatment for sleep problems (10 of 58 [17.2%] versus 21/276 [7.6%], χ 2 =5.28, df=1, p=0.02). After controlling for a history of nonsuicidal self-injury, the use of benzodiazepine was still associated with a faster time to a suicidal event (z=2.96, p=0.003), whereas use of sleep medication was not (z=0.83, p=0.41).

Discussion

During the first 12 weeks of treatment of adolescents with treatment-resistant depression, the incidence of suicidal and nonsuicidal self-injury adverse events were 14.3% and 9.3%, respectively. The rate of all events, although not serious adverse events, was higher when assessed systematically than when obtained by spontaneous report. The strongest predictors of suicidal events were high baseline suicidal ideation, family conflict, and drug or alcohol use, whereas a previous history of nonsuicidal adverse events was the best predictor of nonsuicidal adverse events. There were no main effects of treatment on the frequency of either type of self-harm adverse events, but CBT was associated with an earlier onset of nonsuicidal adverse events. Participants who experienced a suicidal adverse event, but not those with a nonsuicidal adverse event, were less likely to respond treatment. In participants with high suicidal ideation, treatment with venlafaxine was associated with an increased rate of self-harm events compared to those treated with an SSRI. Participants who received an anti-anxiety medication were more likely to experience both suicidal and nonsuicidal self-injury adverse events.

Reliance on spontaneous report of suicidal adverse events will underestimate the rate of events compared to systematic assessment. However, the frequency of serious suicidal or nonsuicidal self-injury adverse events was similar under both conditions. Because the TORDIA trial was not placebo-controlled, these results cannot be directly compared to the placebo-controlled trials in the FDA analysis

(1,

10) . The FDA analysis showed some divergence between measures of systematically assessed suicidal ideation and spontaneous reporting, although other studies have found similar patterns for suicidal events under both conditions

(4,

10,

26) .

The predictors of a suicidal adverse event were high baseline suicidal ideation and depression, self-reported family conflict, and drug or alcohol use, consistent with other reports in the literature

(4 –

6) . Although the clinical characteristics of those with suicidal and nonsuicidal adverse events overlap

(27), the clinical implications of suicidal adverse events were more serious, insofar as the occurrence of suicidal, but not nonsuicidal self-injury, adverse events was associated with a poorer response to treatment. This may be because the above-noted predictors of suicidal adverse events overlap with those that predict poorer response to treatment in depressed adolescents

(28 –

33) . Participants who experienced suicidal events showed a similar slope of decline in their suicidal and depressive symptoms, but because they started at a higher level, they were at greater risk for an event over time than those who entered at lower levels of symptoms. Interventions that speed the relief of depression and help to inhibit acting on suicidal urges could reduce the risk of the occurrence of a suicidal event.

In those participants with high suicidal ideation, treatment with venlafaxine, compared to treatment with an SSRI, was associated with a higher rate of either a suicidal or nonsuicidal self-injury event. Like some studies, but in contrast to others, there was no protective effect of CBT on the occurrence of suicidal adverse events

(4,

26,

34) . Given that the median time to a suicidal event was 3 weeks, participants could not have received an adequate “dose” of CBT before many of these events occurred. Since high ideation, drug and alcohol use, and family conflict predict early onset of suicidal adverse events, these domains should be targeted early in these patients. The association of CBT with earlier onset of nonsuicidal adverse events was probably due to increased contact and monitoring. Nevertheless, CBT treatment failed to attenuate the risk for self-injury, perhaps because contextual and behavioral functions of nonsuicidal adverse events were not emphasized in this treatment model

(35) .

The relationship between the use of benzodiazepines and the occurrence of self-harm events must be interpreted cautiously because of the small number involved, the heavy representation of just one site, and nonrandom assignment. Meta-analyses do not find such an association, although some clinical studies do

(36 –

38) . Possible explanations could include cognitive effects of benzodiazepines resulting in increased risk-taking and disinhibition

(39) .

This study is limited by sample size, the relatively small number of events, and, with regard to the relationship between an event and the use of benzodiazepines, the small number of participants using these nonrandomly assigned agents. On the basis of these findings, especially careful monitoring of more severely depressed patients with high suicidal ideation and family conflict is warranted. Treatments that directly target family conflict and emotion regulation early in the course of treatment may be successful in reducing the occurrence of suicidal adverse events. Although no single study can be definitive, especially for post-hoc analyses, these findings suggest the need to re-evaluate the risks and benefits of venlafaxine and of anti-anxiety agents in treatment-resistant depressed adolescents at high suicidal risk.