Participants

The National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Depression Study recruited inpatients and outpatients who satisfied Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC)

(16) for major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, or schizoaffective disorder from 1978 to 1981. All were seeking treatment at one of five academic centers: Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston; New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia-Presbyterian Hospital in New York City; Rush Presbyterian Hospital in Chicago; Washington University in St. Louis; and the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics in Iowa City. Inclusion criteria required that participants be at least 18 years old, not mentally retarded, English-speaking, Caucasian, and knowledgeable of their biological parents.

In the present study, patients with manic or hypomanic syndromes manifesting before intake or at any time during follow-up were designated as having bipolar disorder. The course of those whose first episode of mania or hypomania appeared during follow-up was nevertheless tracked from study entry. Those with RDC schizoaffective disorder, other than the mainly schizophrenic subtype, were also included. The RDC-defined mainly schizophrenic subtype of schizoaffective disorder is equivalent to DSM-IV schizoaffective disorder, but the remainder of RDC schizoaffective manic or depressed patients nearly all meet DSM-IV criteria for bipolar or major depressive disorder with mood-incongruent psychotic features.

Procedures

After participants provided informed consent, professional raters conducted structured interviews using the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS)

(17) . Item ratings and the resulting diagnoses integrated information from the interview, from review of medical records, and from informants when available.

Follow-up assessments then took place semiannually for the subsequent 5 years and annually thereafter. Raters used the Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation (LIFE)

(18) and later variants (the LIFE-II and the Streamlined Longitudinal Interval Continuation Evaluation) to record descriptions of the clinical course and psychosocial outcome based on direct interview and on medical record review.

These instruments used the LIFE psychiatric symptom ratings to track all RDC syndromes that had been active at intake or that developed during follow-up. Interviewers helped patients identify points at which symptom levels had changed and then quantified symptom levels between those points. For major depression, bipolar disorder, schizoaffective depression, and schizoaffective mania, symptom levels were assigned scores ranging from 1 to 6, with 1 indicating no symptoms, 2 indicating the presence of one or two symptoms to a mild degree, 3 and 4 indicating the continued presence of an episode with less than the number of symptoms necessary for an initial diagnosis, 5 indicating a full syndrome, and 6 indicating a relatively severe full syndrome. An episode was defined as ended after 8 consecutive weeks of psychiatric symptom ratings no greater than 2; a new episode was declared when the patient again met criteria for definite major depression, mania, or schizoaffective disorder. For hypomania, minor depression, and intermittent depressive disorders, symptoms were rated on a 3-point scale in which 3 indicated a full syndrome; recovery was defined as 8 consecutive weeks with ratings of 1.

Data Analyses

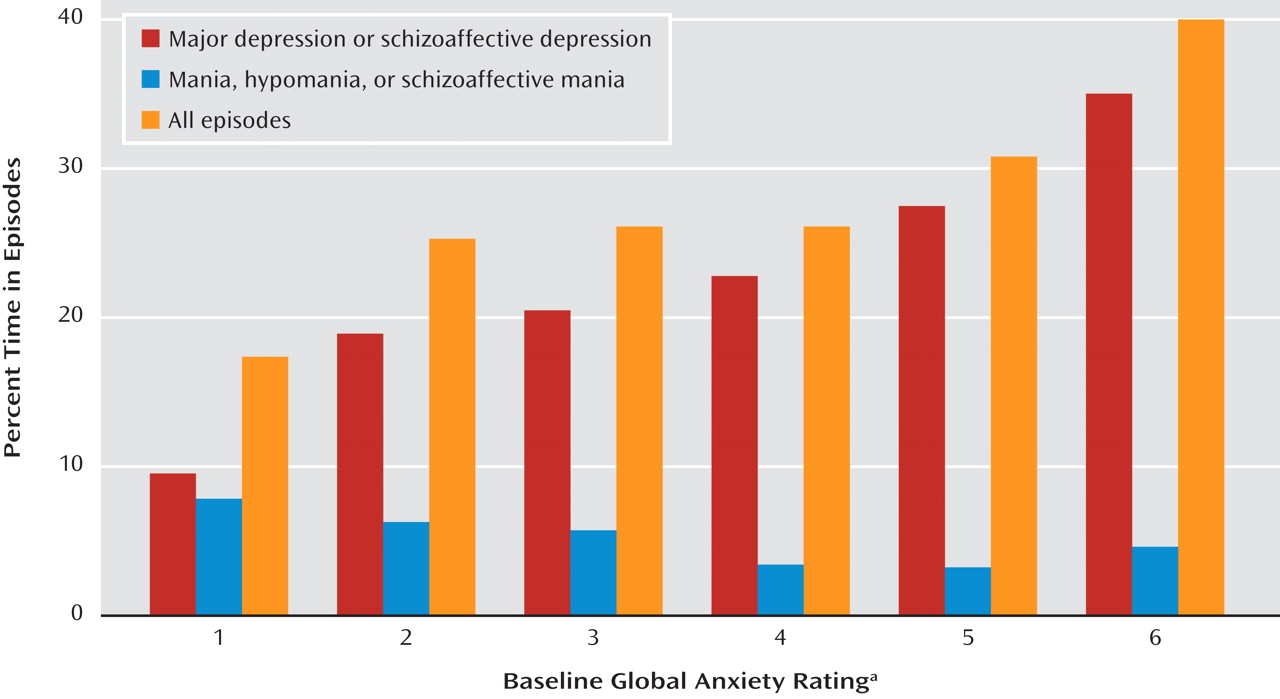

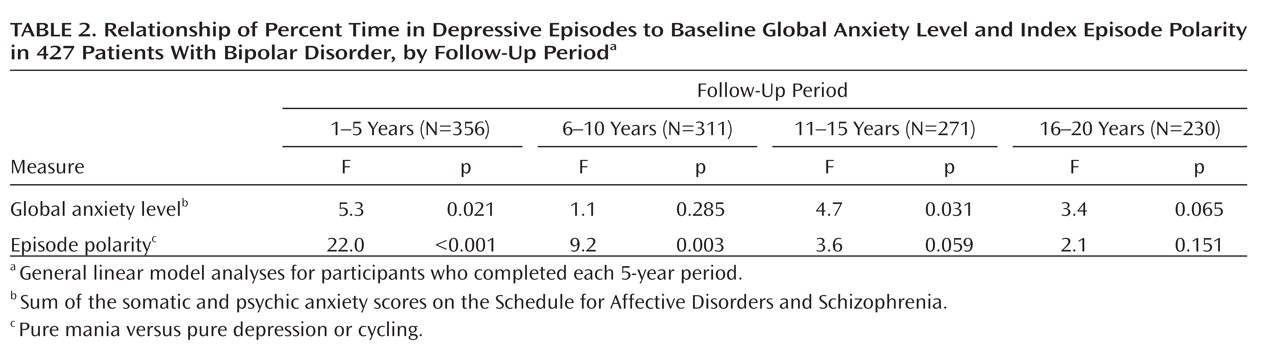

We selected the persistence of depressive episodes as the principal outcome measure because earlier analyses have shown that depression dominates the symptomatic course of the bipolar disorders

(19,

20) . This measure, which we here call “depressive morbidity,” was quantified as the percentage of follow-up weeks in episodes of major, schizoaffective, minor, or intermittent depressive disorders as indicated by psychiatric symptom ratings of 3 or more for any of the syndromes.

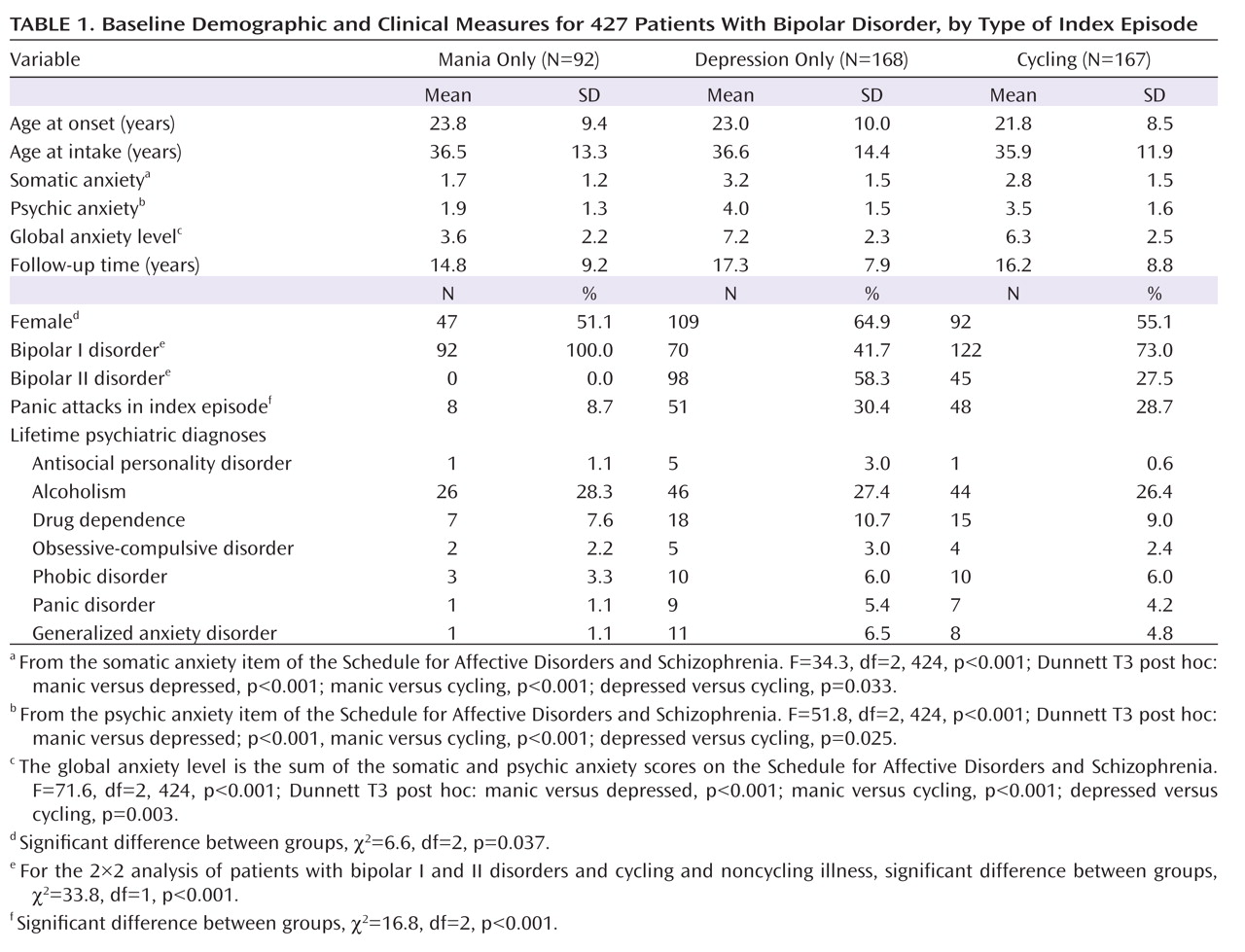

Because the presence or absence of cycling in an index episode, as well as the index episode’s phase, have established prognostic importance

(21 –

24), patients were initially grouped according to the polarity of their intake episode at the time of the baseline assessment as purely manic, purely depressed, cycling, or mixed. Only 11 patients were in mixed episodes, and because mixed states appear (in prognostic terms) simply to be extreme forms of rapid cycling, we included these patients with those who were cycling, as we have done in earlier studies

(25) . The three groups were compared by baseline demographic and clinical measures and by the principal outcome measure, the proportion of weeks of follow-up in depressive episodes, to determine whether these groups should be separated or combined in the analyses of outcome prediction.

We likewise tested for significant relationships between percentage time in depressive episodes and sex, age at intake, lifetime non-anxiety comorbid diagnoses (alcoholism, drug dependence, and antisocial personality disorder), bipolar type (I versus II), intake episode polarity (cycling, pure depressive, or pure manic), and four measures of concurrent anxiety—presence or absence of panic attacks within the index episode, presence of any lifetime RDC anxiety disorder (panic disorder, phobic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or generalized anxiety disorder), and the 6-point SADS ratings of somatic and psychic anxiety (items 263 and 265). The somatic anxiety item specifies “physiological concomitants of anxiety other than during panic attacks” and lists as examples headaches, stomach cramps, diarrhea, and muscle tension. The psychic anxiety item specifies “subjective feelings” of anxiety, fearfulness, or apprehension, excluding panic attacks. The 6-point scales for each range from 1 for no anxiety at all to 6 for “extreme,” indicating “pervasive feelings of intense anxiety.”

These anxiety measures were entered into an SPSS (version 16.0) general linear model to determine which added to the prediction of time depressed. Sex, age at intake, non-anxiety comorbid diagnoses, bipolar type, or episode polarity was included in the model if univariate analysis had shown that factor to have a significant relationship to time depressed.

After selecting the most salient predictor of subsequent morbidity, we tested for the persistence of the relationship by considering depressive morbidity in each of four 5-year periods that comprised the follow-up period. These analyses were restricted to patients who completed the respective 5-year follow-up periods.

These procedures were repeated for the prediction of proportion of weeks in episodes of mania, schizoaffective mania, or hypomania. Two-tailed tests and an alpha of 0.05 were used throughout.