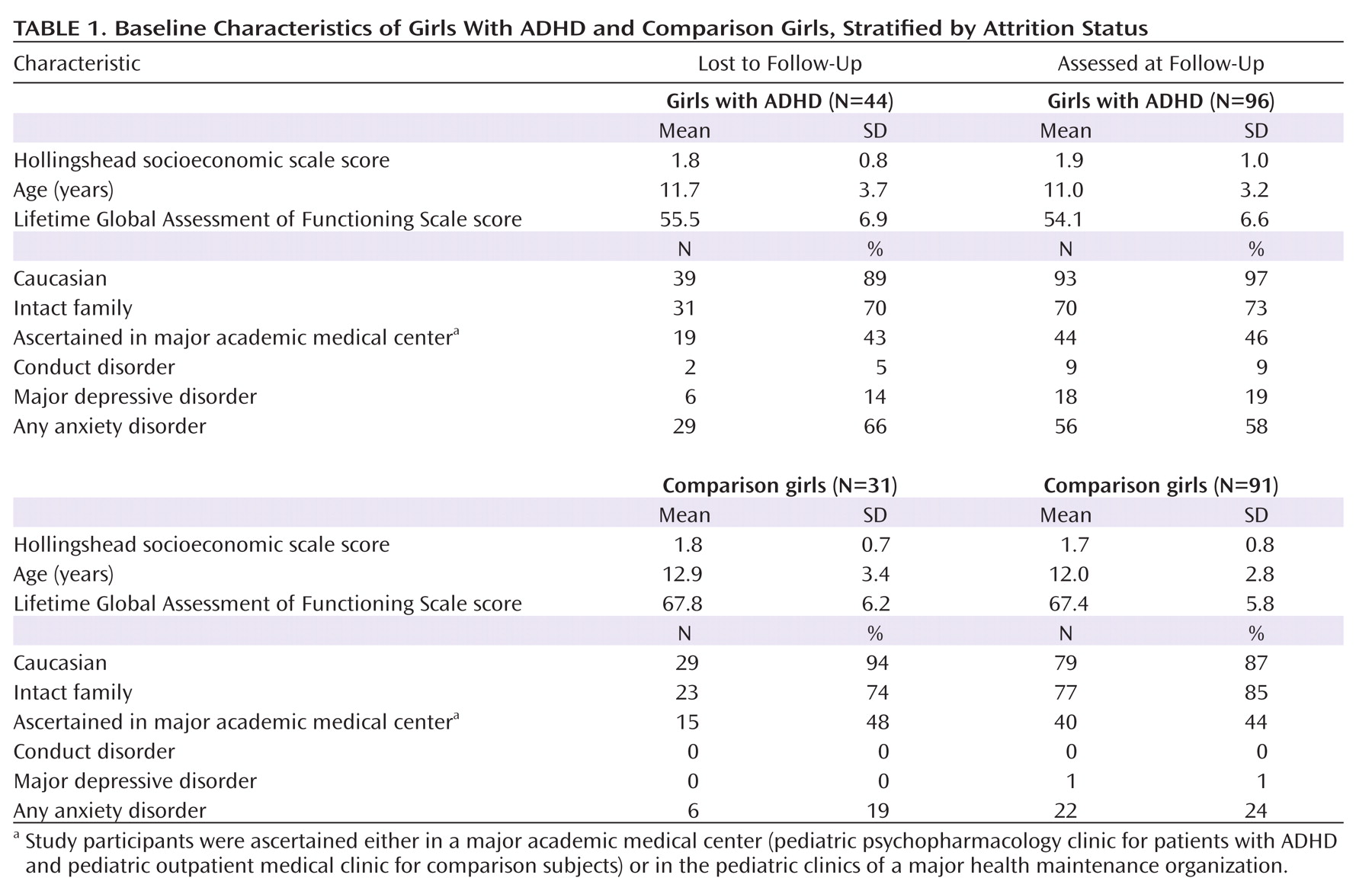

Because almost all the available literature on follow-up studies of ADHD is limited to studies of boys, there is a scarcity of follow-up studies of girls with ADHD. The first follow-up study of girls compared 12 girls and 24 boys with a DSM-II diagnosis of hyperactivity and 24 male comparison subjects (

6). In a community survey (

7), girls identified at baseline as hyperactive were more likely to report academic and interpersonal relationship problems at the adolescent follow-up. We reported results of a 5-year follow-up study into the mid-adolescent years from a sample of girls with DSM-III-R-defined ADHD and comparison subjects (

8). Girls with ADHD were at significantly higher risk for disruptive behavior and mood, anxiety, and addictive disorders in adolescence. Hinshaw et al. (

9) and Owens et al. (

10) reported similar findings in girls followed into adolescence; the majority of girls with ADHD continued to struggle with functional impairments across multiple domains. Although these follow-up studies documented the high morbidity and disability associated with ADHD in girls, no information is available on whether these findings extend to adulthood.

Understanding of outcomes of girls with ADHD in adulthood has clinical and public health implications. Clinically, such information would help in prognosis and would alert clinicians to the importance of recognizing ADHD and associated comorbid disorders in girls for treatment planning and early intervention strategies. From a public health perspective, the ability to predict the outcome of ADHD in girls would help focus limited resources on those individuals who are at higher risk for persistent illness with complicated outcomes.

Here we report results from an 11-year longitudinal study of psychiatrically and pediatrically referred girls with and without ADHD followed into young adulthood. Our main aim was to estimate the burden of psychopathology associated with ADHD in young adulthood. We hypothesized that girls with ADHD would show greater rates of disruptive behavior and mood and anxiety disorders than girls without ADHD. To our knowledge, this is the first prospective study of girls with ADHD followed into young adulthood.

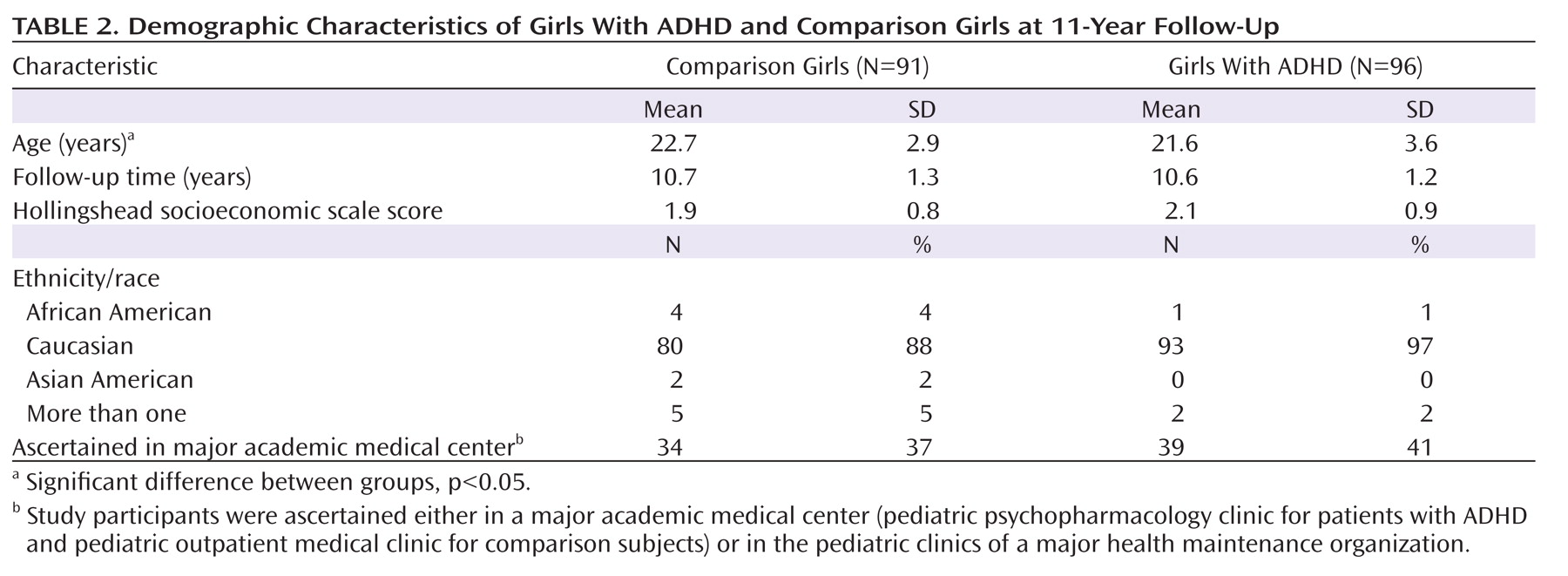

Discussion

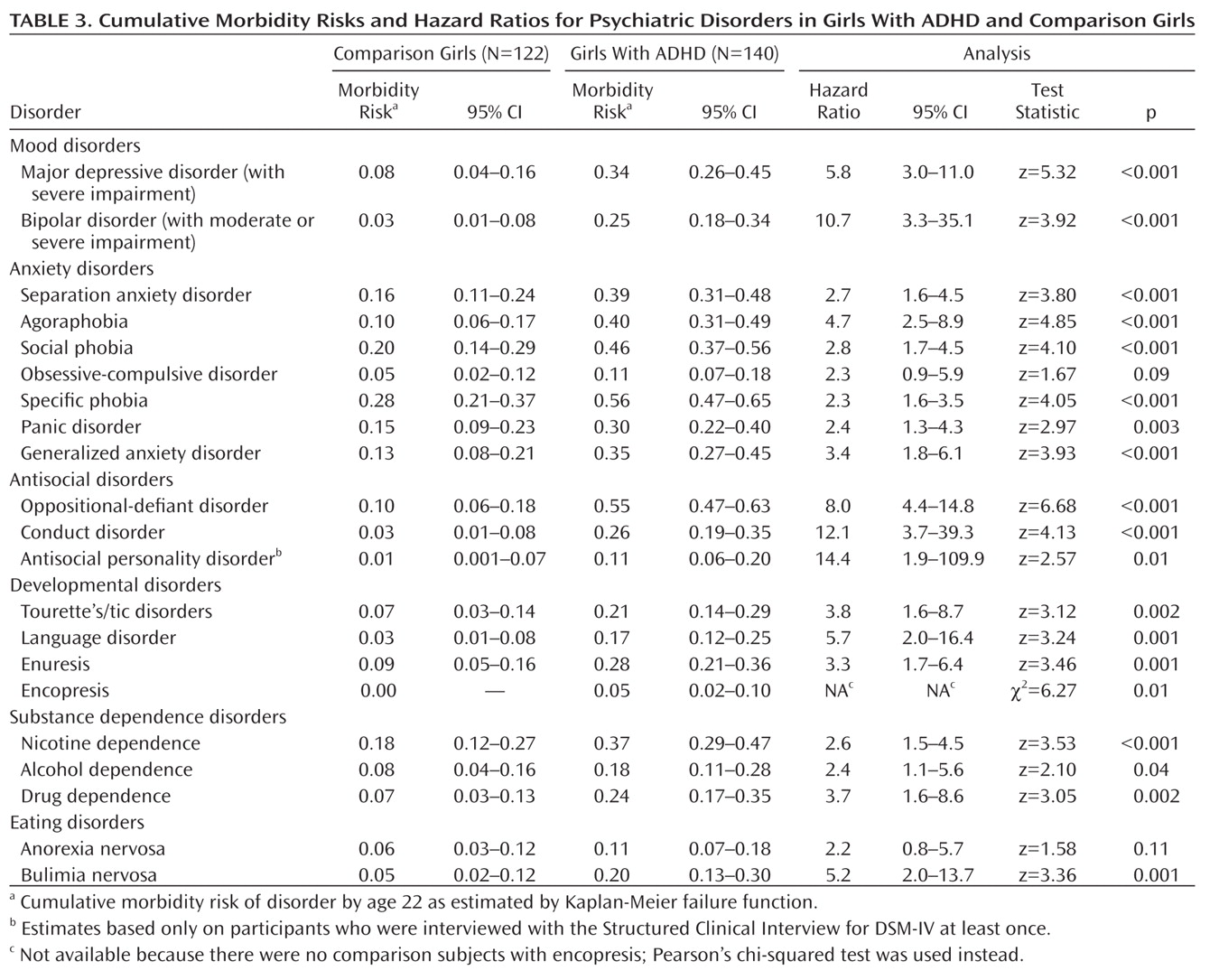

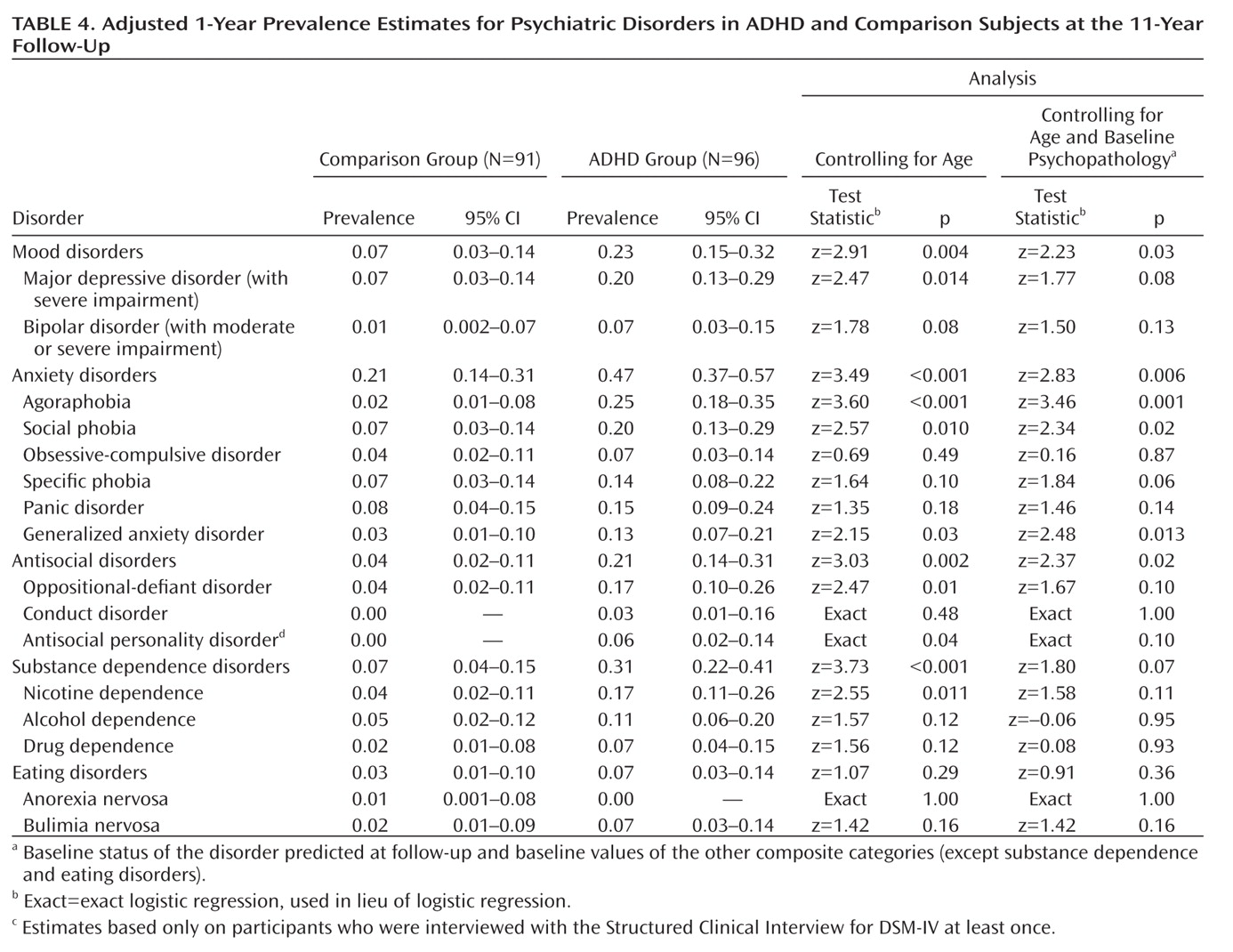

This is the first follow-up study of girls with ADHD into young adulthood and the longest follow-up study of girls with ADHD (11 years). By a mean age of 22 years, 62% of girls with ADHD continued to have impairing ADHD symptoms, which is consistent with a meta-analysis of ADHD follow-up studies (

16). They also had significantly greater lifetime and 1-year risks for antisocial, mood, and anxiety disorders relative to comparison subjects, even after correcting for baseline psychopathology. These results extend to girls findings that were previously documented in boys (

17), stressing the significant psychiatric morbidity associated with ADHD in both sexes across the lifespan. They also stress the critical importance of early recognition of this disorder for prevention and early intervention strategies.

Strengths of this study include the large sample of well-characterized girls with and without ADHD and the long follow-up into young adulthood. This is especially important since few studies have followed youths with ADHD into adulthood, and none has examined girls with ADHD. The lifetime prevalences of psychiatric disorders in the comparison girls are consistent with the prevalences of psychiatric disorders reported in epidemiological studies (

18), supporting the validity of the assessment methodology.

Comparisons of 1-year prevalence estimates between this study and our study of boys with ADHD (

17) reveal a similar pattern of risk for comorbid disorders, which could not be accounted for by either lifetime or 1-year medication use for ADHD. Notable differences include a higher rate of antisocial personality disorder in boys with ADHD grown up compared with girls with ADHD grown up (13% and 6%, respectively) and higher rates of major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders in girls with ADHD grown up compared with boys with ADHD grown up (major depressive disorder, 20% and 8%, respectively; agoraphobia, 25% and 3%, respectively; social phobia, 20% and 4%, respectively). Although boys and girls with ADHD share significant risks for a variety of comorbid disorders, these rates identify different profiles of comorbidity between the sexes in young adulthood.

Our finding that girls with ADHD had significantly greater risks for antisocial disorders, major depression, and anxiety disorders in young adulthood is consistent with the results we obtained at the adolescent follow-up assessment (

8). They are also consistent with Hinshaw and colleagues' report (

9) of elevated rates of externalizing and internalizing disorders in girls with ADHD followed into adolescence. Our results at the adolescent follow-up showed lifetime prevalence rates up to age 25 (

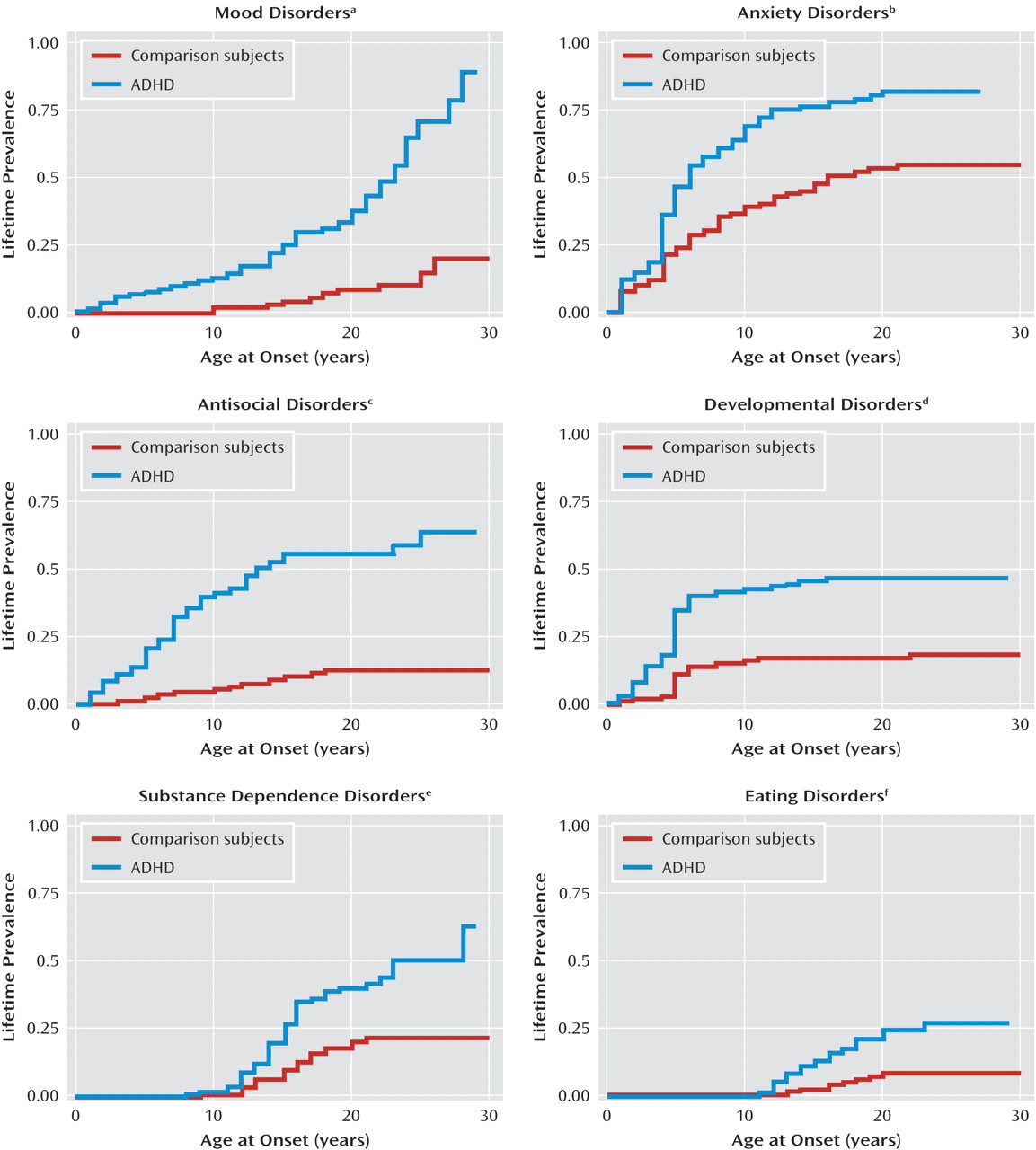

8), while the present analysis shows rates up to age 30. Although lifetime rates of antisocial and anxiety disorders were shown to flatten by age 25, rates of mood disorders continued to climb between ages 25 and 30 (

Figure 1). Therefore, some comorbidities associated with ADHD in girls do not develop until after age 25, which highlights the importance of following this population into adulthood.

The increasing risk for major depression into young adulthood confirms epidemiological surveys (

19), family study data (

20–

23), studies of adults with ADHD (

24), and meta-analytic studies (

25) showing that ADHD is a significant risk factor for major depression. Our findings also confirm studies of referred female adults with ADHD (

24,

26), as well as a report from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication study's representative sample of the U.S. population, which documented elevated rates of major depression and antisocial, addictive, and anxiety disorders in adults with ADHD relative to comparison subjects (

27).

Our findings about bipolar disorder are particularly interesting given controversies about diagnosing the disorder in children, especially those with ADHD, and about discriminating manic symptoms from severe chronic irritability, hyperarousal, and hyperreactivity (

28,

29). Reports of comorbidity between ADHD and bipolar disorder have been questioned because some diagnostic criteria are shared by both disorders. Thus, it is possible that the comorbidity of bipolar disorder and ADHD is due to overlapping diagnostic criteria. However, when Milberger et al. (

30) accounted for overlapping diagnostic criteria, they continued to find significant comorbidity between the two disorders.

Despite ongoing controversy about the diagnosis of pediatric bipolar disorder, these concerns should be interpreted in the context of a large emerging literature supporting the validity of diagnosing bipolar disorder in youths and the fact that two medications, risperidone and aripiprazole, have already gained approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of pediatric bipolar disorder as monotherapy. Notably, a practice parameter from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (

31) and two independent reviews of phenomenological, longitudinal, treatment-response, neuroimaging, neuropsychological, and genetic studies (

32,

33) concluded that bipolar disorder can be validly diagnosed in youths. This literature also shows that pediatric bipolar disorder is frequently persistent, is highly morbid, is commonly associated with significant functional impairment in multiple domains, and is associated with elevated risks for psychiatric hospitalization, antisocial behaviors, addictions, and suicidal ideation. The review by Geller and Tillman (

33) is of particular interest because it showed that pediatric bipolar disorder meets the Robins and Guze criteria for a valid psychiatric disorder.

Our work adds to this literature by reporting that girls with ADHD grown up continue to have an increased risk for bipolar disorder. This finding confirms results from our adolescent follow-up (

8,

34) and is consistent with our studies of female adults with ADHD (

24,

26). It is also consistent with results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication study (

27) documenting a significant and bidirectional association between ADHD and bipolar disorder in adults of both sexes. Moreover, this overrepresentation of bipolar disorder in girls with ADHD grown up is consistent with studies of pediatric (

35) and adult ADHD samples (

24) as well as studies of bipolar children (

36) and adults (

37) documenting a bidirectional association between ADHD and bipolar disorder in both sexes across the lifespan.

The finding that girls with ADHD had an elevated risk for eating disorders in adulthood confirms our report from the 5-year follow-up (

8) and Hinshaw and colleagues' (

9) finding of elevated eating disorder symptoms in their adolescent follow-up study of girls with ADHD. Studies of adult females have also found an elevated prevalence of bulimia in females with ADHD (

24). These results should alert clinicians to a need to monitor young female patients with ADHD for eating disorder pathology.

Our results must be interpreted in the context of methodological limitations. Our lifetime psychopathology outcomes are potentially subject to recall bias, especially in the context of comorbidity. However, in our own work, lifetime diagnoses have shown excellent interrater reliability, as noted in the Method section, and good to excellent test-retest reliability over 1 year (

38). Because our diagnoses of ADHD in some participants relied on self-report, our estimates of prevalence may be lower than they would have been if reports from parents or spouses had been incorporated. Because our sample was referred and mostly Caucasian, our results may not be generalizable to the general population or to other racial or ethnic groups. However, our results should generalize to ADHD girls seen in pediatric and psychiatric settings. Because we did not manipulate treatment as an independent variable, we cannot use our study to determine treatment effectiveness (

39) or to describe the untreated course of ADHD. While our main aim was to assess the outcome of ADHD girls in young adulthood, a small portion of our sample had not yet reached adulthood. Our sample was originally ascertained according to DSM-III-R criteria, and it is possible that our results may not generalize to samples ascertained by DSM-IV criteria. However, considering the very high overlap between the two definitions (93% of DSM-III-R cases received a DSM-IV diagnosis [

40]), any effect should be minimal.

Despite these limitations, in a large sample of girls with and without ADHD followed into young adulthood originally ascertained from pediatric and psychiatric sources, our 11-year follow-up confirms and extends results from the baseline and mid-adolescent assessments. We observed a strong association between ADHD and lifetime risks for antisocial, mood, anxiety, developmental, and substance dependence disorders at the 11-year follow-up. These data provide further evidence for the morbidity and disability associated with ADHD from childhood into young adulthood in individuals of both sexes with ADHD.