Autism spectrum disorders are diagnosed on the basis of social and communication difficulties and the presence of repetitive behaviors and interests. However, in addition to these core impairments, other emotional problems are often observed, including internalizing difficulties such as anxiety (

1,

2) and depression (

3). Recent meta-analyses have reported that up to 84% of children with autism spectrum disorders experience impairing anxiety (

4) and up to 34% experience depression (

3). However, despite this well-reported overlap, few studies have addressed the longitudinal links between these difficulties.

In the present study, the association between autistic-like and internalizing traits was explored across middle to late childhood. By examining traits within a population-representative sample, not solely the clinical extreme, we gained greater power for quantitative genetic analysis (

5). First, we tested whether autistic-like traits at age 7 predicted the level of internalizing traits at age 12. Second, we explored the reverse association, whereby earlier internalizing traits influence the subsequent development of autistic-like traits. This direction of effect is in line with findings of increased autistic-like traits in individuals with internalizing disorders (

6,

7), suggesting that internalizing traits might exacerbate autistic-like difficulties. Finally, we considered whether there are bidirectional processes underlying this association.

A genetically informative cross-lagged design was used to estimate the phenotypic-driven processes by which internalizing and autistic-like traits affect one another over time. This model constrains all associations to take the form of partial regression coefficients, estimating the strength of the longitudinal relationship between the traits while controlling for their preexisting association at the earlier timepoint. This is the first study, to our knowledge, to use the cross-lagged model to assess autistic-like traits, although it has been used previously to disentangle other longitudinal relationships in the behavioral problems literature (

8–

10). We also explored, phenotypically, the impact of particular types of autistic-like traits on later internalizing traits. That is, are there distinguishable effects of communication impairments, social difficulties, and repetitive behaviors on later internalizing difficulties?

Previous investigations using the Twins' Early Development Study (

11) sample have revealed high heritabilities for autistic-like traits (

12,

13), moderate heritabilities for internalizing traits (

14), and only modest levels of genetic overlap between these two traits at ages 8 and 9 (

15). Our study extended these findings by taking a longitudinal approach. We predicted that there would be a bidirectional relationship, with autistic-like traits earlier in childhood directly influencing the level of later internalizing traits and vice versa. We predicted a significant level of stability in both traits across childhood, with only modest levels of etiological overlap between them. We also predicted that all three types of autistic-like traits would contribute significantly to the variance of later internalizing difficulties.

Method

Participants

Data were obtained from the Twins' Early Development Study (

11), a population-representative sample of twins born in England and Wales from 1994 to 1996. Written informed consent was obtained from all parents. A total of 7,834 families returned the questionnaires when their twins were age 7, 6,762 families returned them when their twins were age 8, and 5,876 families returned questionnaires when their twins were age 12. Families were excluded if severe pre- or postnatal complications were reported or if one twin had a severe medical condition (see reference

16). This led to a total of 523 families being excluded from the age 7 twin cohort, 336 families from the age 8 twin cohort, and 200 families from the age 12 twin cohort.

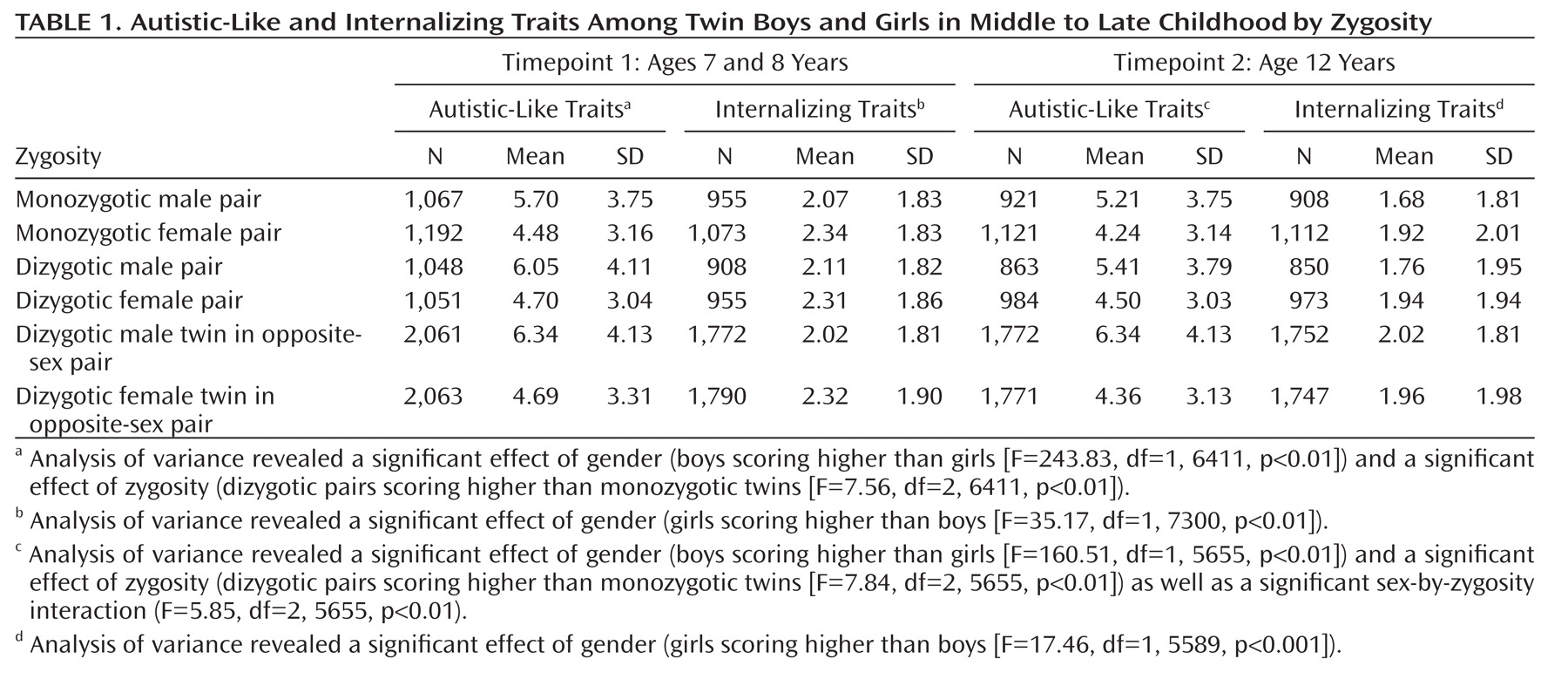

Table 1 summarizes the zygosity of the sample following these exclusions. Zygosity was determined using parent ratings of similarity (

17), supplemented by DNA genotyping. The sample consisted of children across the full spectrum of autistic-like traits, including a small percentage of children (age 8: 1.2%; age 12: 1.8%) who scored above the cutoff point of 15 for a diagnosis of potential autism spectrum disorder according to the Childhood Autism Spectrum Test criteria (formerly known as the Childhood Asperger Syndrome Test [

18,

19]). We refer to ages 7 and 8 as timepoint 1 and age 12 as timepoint 2.

Measures

Autistic-like traits. Autistic-like traits were assessed at ages 8 and 12 using the parent-reported Childhood Autism Spectrum Test (

18). The test includes 31 key items (and six control items) scored with a "yes/no" response and is reported to be sensitive and specific (

19), with good construct validity and test-retest reliability (

20). The test showed strong internal consistency at ages 8 (alpha of 0.73) and 12 (alpha of 0.78). We also used specific subscales at age 8 to assess social difficulties (12 items: alpha of 0.56), communication difficulties (12 items: alpha of 0.64), and repetitive behaviors (seven items: alpha of 0.49).

Internalizing traits. Internalizing traits were measured at ages 7 and 12 using the emotional problems subscale of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (

21). This subscale consists of five items answered using a three-point Likert scale (never=0; sometimes=1; often=2). Two items assess anxiety, two assess depression, and one measures somatic symptoms. The responses to the items showed moderate internal consistency at age 7 (alpha of 0.63) and age 12 (alpha of 0.68). Previous studies have supported the reliability and sensitivity of this questionnaire (

22,

23) and have validated these items relative to those of the Child Behavior Checklist (

24,

25) and Rutter questionnaires (

26).

Statistical Analyses

Twin method

The twin method allowed us to determine the relative influences of additive genetic factors ("A"), shared environmental factors ("C"), and nonshared environmental factors ("E") on a trait (the ACE model). Shared environmental factors serve to make children within a family similar to each other, whereas nonshared environmental factors result in differences between siblings. The twin design assumes that monozygotic twin pairs share all of their genetic information, dizygotic twins share 50% of their genes on average, and all twins experience the same shared environmental influences (see reference

5).

Autistic-like and internalizing trait scores were calculated if >90% of the items were available. Prior to modeling, the scores were log transformed to reduce positive skew and regressed for age and sex according to standard procedures.

Statistical analyses were carried out using the structural equation modeling Mx program (

27). The following three types of correlations were calculated: phenotypic correlations (r

ph: trait 1 in twin 1 correlated with trait 2 in twin 1), intraclass twin correlations (trait 1 in twin 1 correlated with trait 1 in twin 2), and cross-trait cross-twin correlations (trait 1 in twin 1 correlated with trait 2 in twin 2). These correlations were established at each timepoint as well as longitudinally.

Cross-Lagged Model

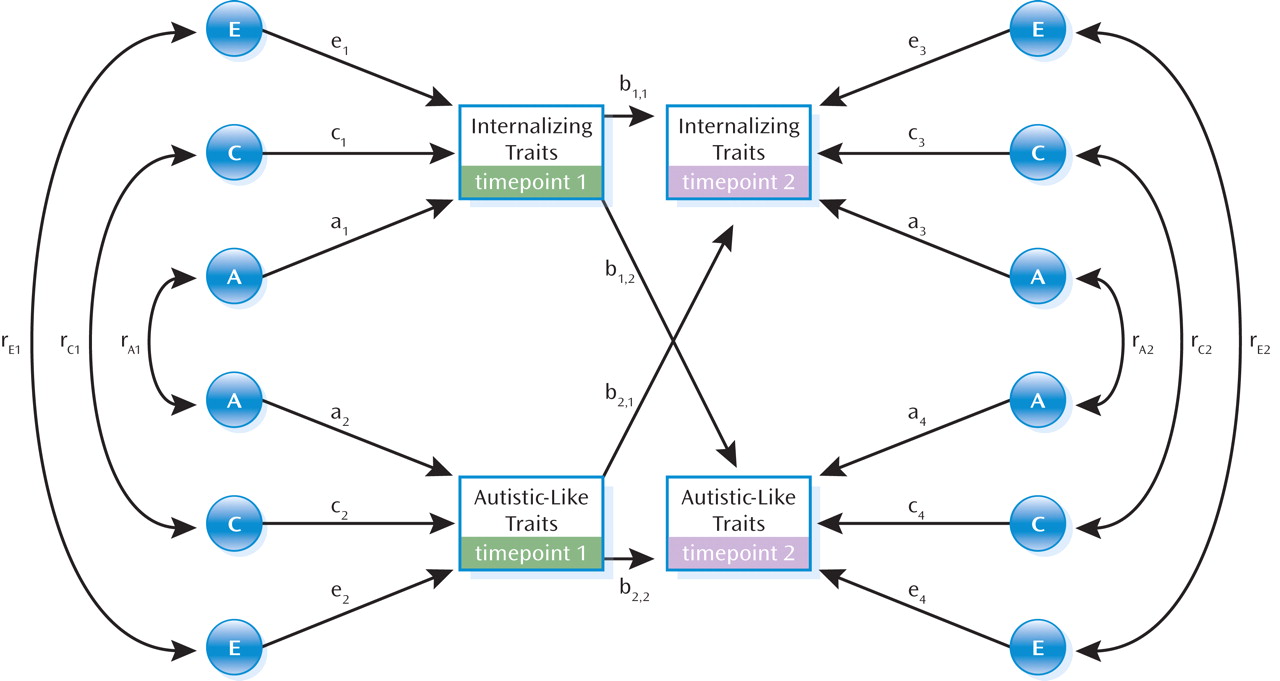

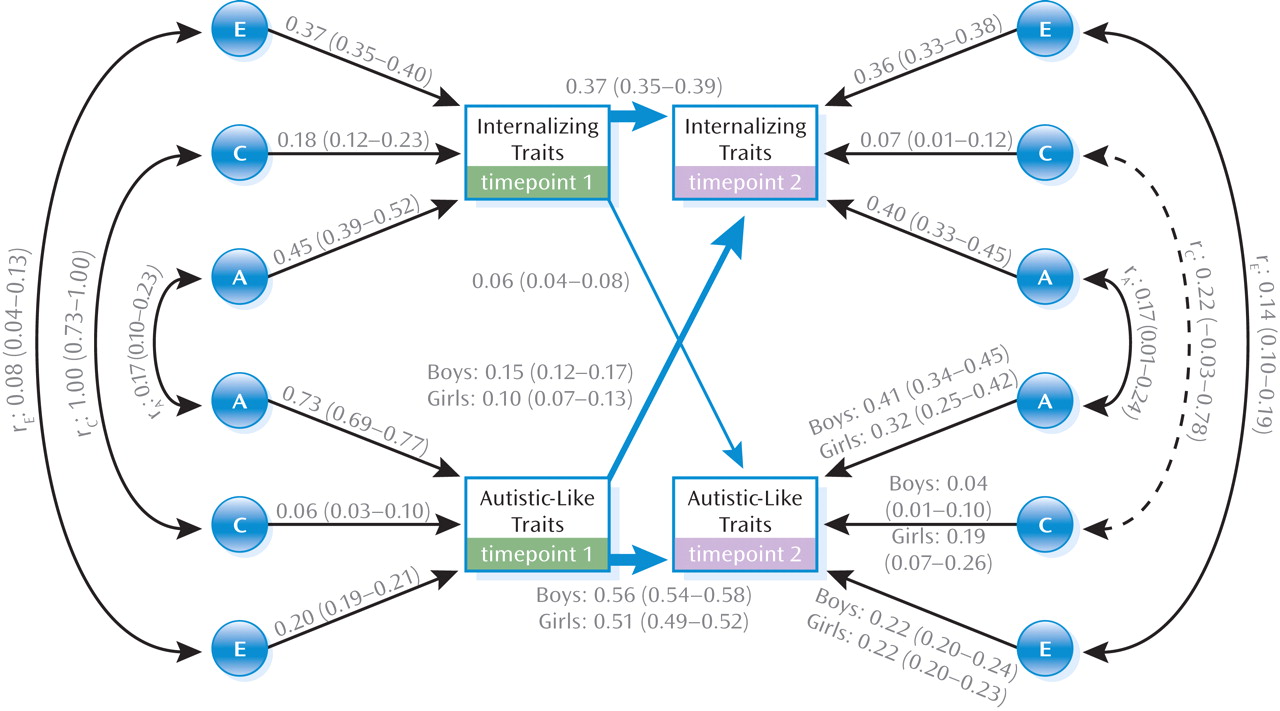

The cross-lagged model is shown in

Figure 1. Cross-lagged associations functioned as partial regression coefficients to illustrate stability in autistic-like traits (b

2,2) and internalizing traits (b

1,1) and the contribution of autistic-like traits at timepoint 1 (ages 7 and 8) to internalizing traits at timepoint 2 (age 12) (b

1,2) and vice versa (b

2,1). The estimates take into account the preexisting association between the two traits at timepoint 1.

The cross-lagged model estimated the relative contribution of genetic and environmental influences to individual traits at timepoints 1 and 2. For example, internalizing traits at timepoint 1 were influenced by genetic (a12), shared environmental (c12), and nonshared environmental (e12) factors. These estimates were also calculated at timepoint 2 (a32, c32, e32), taking into account the influences at timepoint 1.

The model also estimated the etiological influences on the covariation between the traits at both timepoints. For example, at timepoint 1 this included additive genetic (rA1), shared environmental (rC1), and nonshared environmental (rE1) correlations. A correlation of one suggested that the same influence affected both traits.

Transmission of etiological influences over time. The genetic and environmental influences on the variances of autistic-like and internalizing traits at age 12 could be broken down into influences that were specific to timepoint 2 and influences that were shared with autistic-like and internalizing traits at timepoint 1. For example, the total genetic variance of autistic-like traits at timepoint 2 could be analyzed as genetic influences that were shared with autistic-like traits at timepoint 1 (stability effects: b2,22×a22); specific to internalizing traits at timepoint 1 (cross-lagged effects: b1,22×a12); associated with the covariation between the two traits at timepoint 1 (common effects: 2×[b2,2×a2×rA1×a1×b1,2]); and specific to autistic-like traits at timepoint 2 (residual effects: a42).

Initially, all parameter estimates were allowed to differ for boys and girls, with only the values for genetic, shared environmental, and nonshared environmental correlations at both time points constrained to be equal across the sexes, according to standard procedure. Subsequently, parameter estimates and partial regression coefficients were equated for male and female subjects at timepoints 1 and 2. Each cross-lagged model was compared with a saturated model using likelihood ratio chi-square tests, with lower values of -2-log likelihood and Akaike information criterion reflecting a better fit.

Phenotypic Analyses of the Influence of Individual Autistic-Like Traits on Later Internalizing Traits

Pearson's correlations were carried out for the autistic-like traits subscale ratings at timepoint 1 and internalizing traits at timepoint 2. One twin per zygotic pair was selected at random to maintain independence among the cases.

Regression analyses were used to determine how much of the variance in internalizing traits at timepoint 2 could be attributed to each of the subscale ratings at timepoint 1, controlling for internalizing traits at timepoint 1. Univariate regressions were used to determine whether each individual subscale rating was significantly associated with later internalizing. If significant, each subscale rating was then included in a multiple regression.

Results

Summary statistics are shown in Table 1. Scores at timepoint 2 were significantly lower than scores at timepoint 1 for both internalizing traits (t=11.76, df=5007, p<0.01) and autistic-like traits (t=6.90, df=4680, p<0.01). Boys scored significantly higher than girls on the Childhood Autism Spectrum Test at both timepoint 1 and timepoint 2. Conversely, girls scored significantly higher than boys for internalizing traits at timepoint 1 and timepoint 2. Zygosity had a significant effect on the mean scores for autistic-like traits, with dizygotic pairs scoring significantly higher than monozygotic twins at timepoint 1 and timepoint 2. A significant sex-by-zygosity interaction was observed for autistic-like traits at timepoint 2, with boys in opposite-sex pairs scoring higher than other male participants and girls in opposite-sex pairs scoring lower than other female participants.

Correlations

Phenotypic correlations

There was significant (p<0.01) stability over time in autistic-like traits (boys: rph=0.59; girls: rph=0.55) and internalizing traits (boys: rph=0.42; girls: rph=0.42). There were modest associations between autistic-like traits at timepoint 1 and internalizing traits at timepoint 2 (boys: rph=0.22; girls: rph=0.20) and between internalizing traits at timepoint 1 and autistic-like traits at timepoint 2 (boys: rph=0.24; girls: rph=0.20).

Intraclass twin correlations

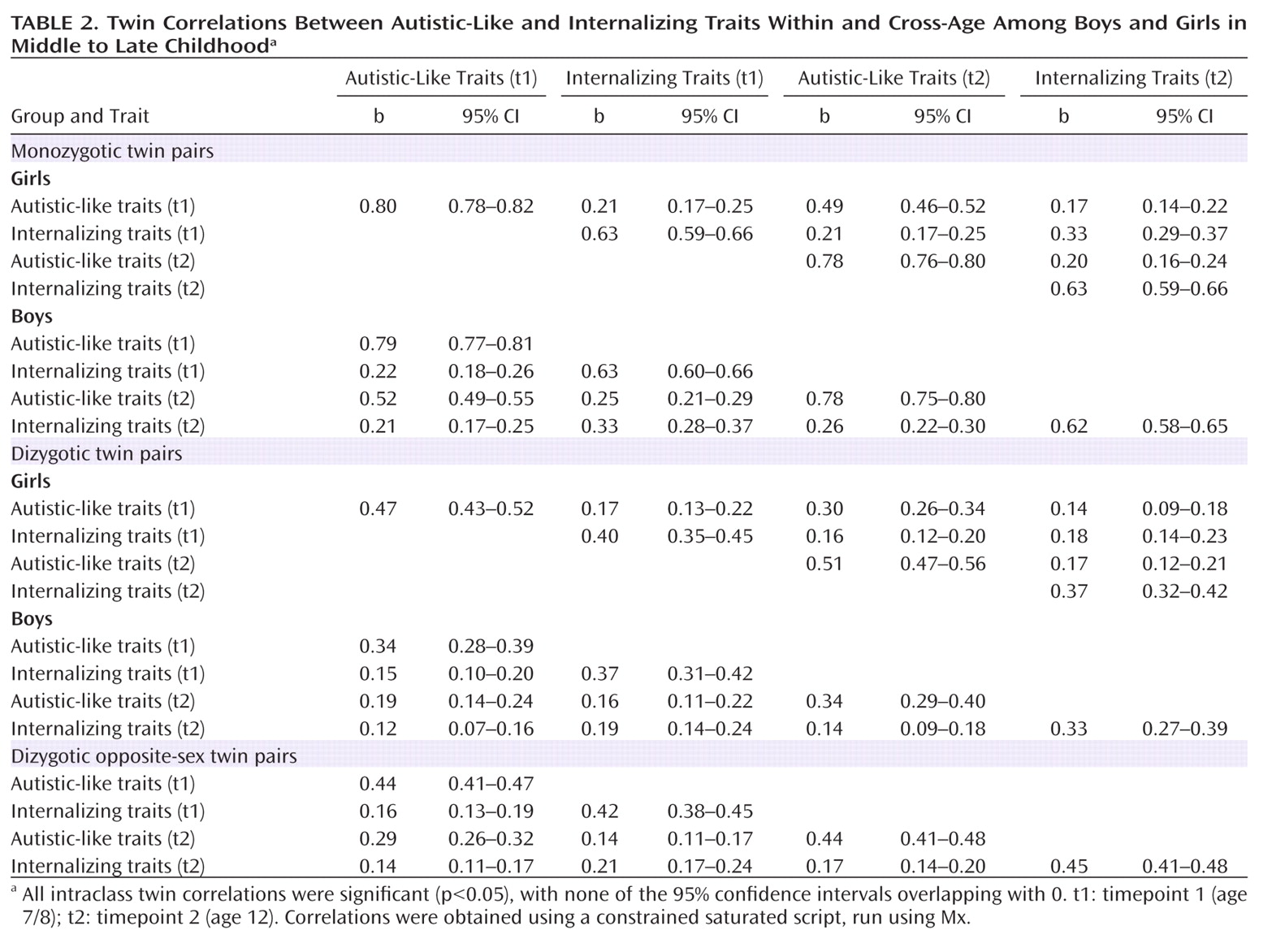

As seen in

Table 2, correlations were significantly higher for monozygotic twin pairs relative to dizygotic twin pairs for both traits at timepoints 1 and 2, indicating significant genetic influences. The correlations suggested low levels of genetic dominance effects for male autistic-like traits (the number of dizygotic male twin correlations was less than one-half the number of monozygotic male correlations). For girls, correlations indicated shared environmental influences for both traits (the number of dizygotic female twin correlations was more than one-half the number of monozygotic female correlations).

Cross-trait cross-twin correlations

At timepoints 1 and 2, there was a modest association between the autistic-like trait score for twin 1 and the internalizing trait score for twin 2. Monozygotic twin correlations were modest and less than double the dizygotic correlations, indicative of low levels of genetic overlap.

Longitudinal correlations

Monozygotic within-trait across-time correlations were moderate and higher than dizygotic correlations, suggesting a significant genetic influence on the stability of both traits over time.

Cross-Lagged Model

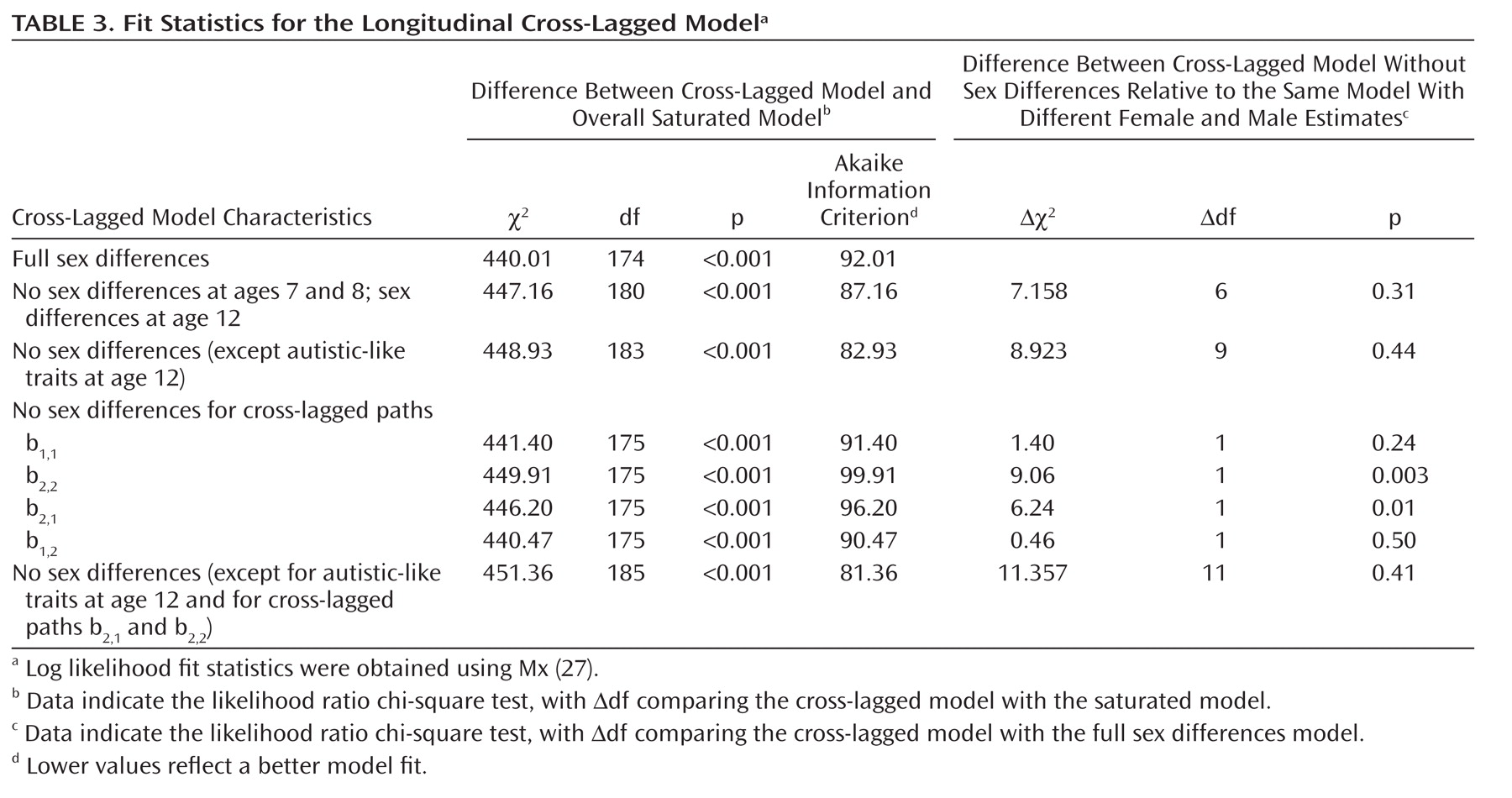

Fit statistics for the cross-lagged model are shown in

Table 3. The model provided a worse fit for the data than the saturated model. This is a common finding when using multivariate models (

8), attributable to the large number of constraints that are imposed. In large samples, the additive effects of small differences are picked up as significant, decreasing the overall fit.

Male and female parameter estimates could be equated for both traits at timepoint 1, for internalizing traits at timepoint 2, and for the cross-lagged paths of coefficients b

1,1 and b

1,2 without significantly worsening the fit. Results from the best fitting model are shown in

Figure 2.

Cross-Lagged Associations

When each coefficient was fixed at 0, a deterioration in fit was observed (b2,1: ʔχ2=134.71 for Δ2df, p<0.01; b1,2: Δχ2=69.76 for Δ2df, p<0.01), suggesting that all cross-lagged paths were significant.

A similar pattern was observed for both sexes

First, there was a significant influence (p<0.01) of autistic-like traits at timepoint 1 on internalizing traits at timepoint 2 (boys: b2,1=0.15; girls: b2,1=0.10). Second, there was a significant, although more modest, influence (p<0.01) of internalizing traits at timepoint 1 on autistic-like traits at timepoint 2 (b1,2=0.06). Third, there was a significant level of stability (p<0.01) over time for internalizing traits (b1,1=0.37) and particularly autistic-like traits (boys: b2,2=0.56; girls: b2,2=0.51). That is, the variance in autistic-like traits at age 12 was somewhat attributable to autistic-like traits at ages 7 and 8 (boys: b2,2=0.562 [31%]; girls: b2,2=0.512 [26%]) and a modest proportion of the variance of internalizing traits at timepoint 2 was explained by internalizing traits at timepoint 1 (14%).

Genetic and Environmental Influences

Univariate modeling showed that genetic dominance was nonsignificant for both traits. As such, the model estimated A, C, and E parameters only. Heritability estimates were high for autistic-like traits at timepoint 1 (73%), with moderate nonshared environmental effects (20%) and a small influence of shared environment (6%). All three parameters were significant, since confidence intervals did not overlap with 0. Figure 2 also presents the proportion of A, C, and E components specific to timepoint 2. As described previously, we could calculate the overall influences of A, C, and E components on each trait at timepoint 2 (e.g., the overall heritability of autistic-like traits at timepoint 2 is the sum of genetic influences shared with autistic-like traits at timepoint 1, genetic influences shared with internalizing traits at timepoint 1, genetic influences as a result of the association between the two traits at timepoint 1, and new effects at timepoint 2). The pattern of etiological influences at timepoint 2 was similar to timepoint 1 for the C component (boys: shared environmental estimate=0.07; girls: shared environmental estimate=0.21) and E component (boys: nonshared environmental estimate=0.29; girls: nonshared environmental estimate=0.27), although heritability estimates (component A) were slightly lower (boys: genetic estimate=0.65; girls: genetic estimate=0.52).

Internalizing traits were moderately heritable at timepoint 1 (0.45), with a moderate influence of nonshared environment (0.37) and a small but significant influence of shared environment (0.18). At timepoint 2, overall parameter estimates were similar for the A (0.49) and E (0.42) components, with a slightly lower estimate for the C component (0.08). There was a significant but modest genetic correlation between the traits (timepoint 1: rA=0.17; timepoint 2: rA=0.17) and low levels of nonshared environmental overlap (timepoint 1: rE=0.08; timepoint 2: rE=0.14). Shared environmental influences correlated more highly between the two traits at timepoint 1 (rC=1.00 [0.73 to 1.00], although there was a nonsignificant estimate of shared environmental influences at timepoint 2 (rC=0.22[–0.03 to 0.78]).

Transmission of Etiological Influences

A table detailing the transmission of etiological influences is available in the data supplement accompanying the online version of this article, since these results do not form a core focus of this study. Some genetic influences on internalizing traits at timepoint 2 were transmitted from timepoint 1 (12%–17%), while most were specific to timepoint 2 (78%–82%). Nonshared environmental influences on internalizing traits were also mainly specific to timepoint 2 (86%–88%), while some were transmitted from timepoint 1 (12%). A small proportion of shared environmental effects were transmitted from timepoint 1 (15%–25%), some were shared with autistic-like traits at timepoint 1 (0.8%–2%), and some were shared with the covariance between internalizing and autistic-like traits at timepoint 1 (8%–13%). For additional information, see the data supplement.

There was significant stability in the genetic influences of autistic-like traits over time, with 35%–37% of influences at timepoint 2 transmitted from timepoint 1. There were also new genetic influences specific to the later time point (61%–63%). A small proportion of nonshared environmental influences was transmitted over time (19%–21%), while others emerged at timepoint 2 (71%–79%). A modest proportion of shared environmental influences at timepoint 2 was explained by autistic-like traits at timepoint 1 (24%–29%), internalizing traits at timepoint 1 (0.5%–1.4%), and their covariance at timepoint 1 (5%–14%).

Phenotypic Analyses of the Influence of Individual Autistic-Like Traits on Later Internalizing Traits

Pearson's correlations showed that all three autistic-like traits subscales at timepoint 1 correlated significantly with internalizing traits at timepoint 2 (p<0.01). Communicative difficulties (r=0.27) and repetitive behaviors (r=0.15) correlated most strongly with later internalizing traits, whereas social difficulties showed a weaker association (r=0.08). There was a strong significant correlation between internalizing traits at timepoints 1 and 2 (r=0.46, p<0.01).

In univariate regressions, all three subscale ratings significantly predicted internalizing traits at timepoint 2, albeit weakly, and thus were included in the full model (social skills: standardized β=0.03, p=0.01; communication skills: β=0.15, p<0.01; repetitive behaviors: β=0.07, p<0.01). In the full model, internalizing traits at timepoint 1 accounted for 46% of the variance in later internalizing traits (p<0.01). Further to this, social skills ratings made no additional contribution to the variance of internalizing traits at timepoint 2, and repetitive behaviors accounted for only 3% of the variance. Communication difficulties at timepoint 1 showed the strongest association with internalizing traits at timepoint 2, accounting for 14% (p<0.01) of the variance, after controlling for earlier levels of internalizing traits.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this represents the first study to address the longitudinal links between autistic-like traits and internalizing traits across childhood. Our results point to an asymmetric bidirectional relationship between these traits. Autistic-like traits at timepoint 1 (ages 7 and 8) had a direct, although modest, phenotypic influence on the development of internalizing traits at timepoint 2 (age 12). The reverse association was also significant, with internalizing traits having a significant, albeit smaller, impact on later autistic-like traits.

Our findings suggest that autistic-like traits in later childhood were driven in part by earlier internalizing difficulties. For example, anxieties in earlier childhood may reduce opportunities for developing effective social communication skills with peers. Furthermore, a child that is easily distressed may cling to routines and may use repetitive behaviors to soothe high levels of arousal (

28). That said, the reverse association was approximately twice as strong, implying that early autistic-like difficulties may have a more pronounced impact on subsequent anxiety and depression than vice versa. For instance, children who struggle with social interactions and communication may shy away from group situations and may find it difficult to express themselves and seek support. Similarly, adhering to rigid routines and rituals may also become more stressful as children progress through school.

Internalizing and autistic-like traits showed significant stability across a 5-year period. This is in agreement with a study of 8- to 15-year-old children with and without autism spectrum disorders, which found significant stability in social difficulties over time (

29). Similarly, studies have also shown stability in internalizing symptoms throughout childhood and adolescence (

30,

31). In line with previous findings, we found a high heritability for autistic-like traits and moderate heritability for internalizing traits (

12,

14,

32). However, although significant, there were only low levels of genetic overlap between the two traits. This finding is consistent with a previous study of the present sample (

15), which found a similarly low level of genetic overlap when the twins were 9 years old. Therefore, despite reciprocal phenotypic processes underlying these traits, the overlap does not appear to be driven by substantial shared genetic influences.

In contrast, there was a stronger association between the shared environmental influences on the two traits, particularly at ages 7 and 8. This finding should be interpreted with some caution because of the large confidence intervals and modest influence of shared environmental factors on autistic-like traits. However, it suggests that environmental factors, such as parental and home influences, may be important. For example, the opportunities that parents provide for socialization may impact children's social and communication skills. Similarly, parents may model coping styles that influence how children react to stress. While it is difficult to speculate about the mechanisms underlying the overlap between these traits, a focus on these environmental factors, rather than a shared genetic pathway, may be beneficial, at least within the general population.

Although not central to our aims, the model also addressed the transmission of etiological influences on autistic-like and internalizing traits over time. There was moderate continuity in the genetic factors involved at both time points, most notably for autistic-like traits. However, the majority of genetic factors were age-specific, pointing to the emergence of novel sets of influences at different developmental stages. A similar pattern of specificity was observed for environmental influences, possibly reflecting the key changes in schools and friendships across this period. Recent studies of internalizing (

31,

33) and autistic-like traits (

29) have emphasized their dynamic nature, highlighting both stability and change across development.

Autistic-like traits affected internalizing traits, but which subtypes of autistic-like traits were driving this association? Our findings suggest that earlier communication difficulties contributed most strongly to later internalizing traits. It seems logical that communicative impairments may confuse a child's understanding of other people, limit self-expression, and reduce strategies for coping with worries and sadness. Conversely, social difficulties at timepoint 1 did not significantly predict later internalizing traits. This unexpected finding may point to a complex relationship between social motivation and ability (as measured by the Childhood Autism Spectrum Test) and anxiety and depression. For example, a child with elevated social autistic-like traits may also lack the insight to reflect on his or her difficulties and to worry about evaluation by peers. In addition, children with communication difficulties who have more social insight might suffer greater anxiety about their own difficulties.

Further research is required to explore how these population-based findings translate to clinical samples of children with autism spectrum disorders and internalizing disorders. Children with autism spectrum disorders frequently experience anxiety (

4,

34), while children with internalizing disorders exhibit heightened autistic-like traits (

6). As such, we can speculate that a similar reciprocal relationship may be observed in clinical groups. Our findings also highlight the importance of differentiating between the effects of different subtypes of autistic-like traits. This may help to both refine our understanding of internalizing difficulties in autism and to inform the most effective targets for intervention.

This study benefitted from the use of a large sample and incorporating the same measures at two ages. However, a number of limitations must be considered. First, the cross-lagged model incorporated only parental-report measures. To reduce rater bias and correlated measurement error, future studies should use additional informants and/or behavioral observation. Second, the internalizing traits measure revealed modest internal consistency and incorporated only five items. A more detailed measure could help capture a wider range of internalizing difficulties. Third, both of the traits analyzed are heterogeneous, both phenotypically and genetically (

13,

14), and thus further investigation is needed to address the relationship between specific internalizing subtypes and specific autistic-like traits. Finally, there are also some limitations inherent to the twin design (

5) and the cross-lagged model (

8). The modest cross-lag associations suggest that there are additional factors (not included in the model) that influence these traits over time.

Our results provide support for a modest bidirectional relationship between autistic-like and internalizing traits across childhood, with a particularly prominent influence of autistic-like traits on subsequent internalizing. It is important to consider how these results might translate to different developmental stages and clinical groups. If autistic symptoms, particularly communication difficulties, serve to exacerbate internalizing symptoms, promoting early communication skills may help to reduce later internalizing difficulties. Similarly, we can speculate that attempts to reduce stress in childhood might be somewhat protective against the worsening of later social communication problems.