In addition to the use of antidepressants to treat acute depression or anxiety, prolonged antidepressant treatment is widely used to limit the high risk of relapse or recurrence (

1–

5). Overall, antidepressant sales rank third worldwide among all drugs (

6) and are the leading prescription drug class in the United States among patients 18–64 years of age (

7). They are prescribed more frequently by primary care physicians than by mental health specialists (

8,

9). The effects of antidepressant withdrawal are of clinical and public interest. Stopping antidepressant treatment, especially abruptly, can provoke physiological withdrawal reactions, especially with short-acting serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and perhaps also with tricyclic antidepressants (

10–

19). Such reactions include somatic symptoms (gastrointestinal and other general somatic distress, including dysesthesias and paresthesias), movement disorders (bradykinesia and akathisia), and neuropsychiatric distress (typically anxiety and agitation, sleep disturbances, impaired cognition, and activation or mania) (

10–

18,

20).

In addition to physiological withdrawal syndromes associated with some antidepressants, stopping long-term treatment with some agents can increase the risk of new episodes of illness and reduce the time to new episodes (

1). Evidence for such an effect has been found for lithium in bipolar disorder (

21,

22) and neuroleptics in psychotic disorders (

23). Also, in a review comparing discontinued and continued long-term antidepressant treatment (

1), we found that the overall 12-month recurrence risk was 2.3 times higher among patients who discontinued treatment, and the median time to a first depressive recurrence was one-third that of those who continued. Such contrasts may reflect loss of long-term prophylactic effectiveness or a confounding impact of treatment discontinuation itself (

1,

21).

We found much shorter latency to occurrence of new mania or bipolar depression after stopping lithium abruptly versus gradually (

24,

25) and earlier exacerbations of schizophrenia after discontinuing antipsychotics rapidly versus gradually (

23). It is also noteworthy that physiological syndromes associated with antidepressant withdrawal appear to be more likely to occur with relatively rapidly cleared serotonin reuptake inhibitors (e.g., paroxetine and venlafaxine, as opposed to citalopram and fluoxetine), whereas effects of gradual dose tapering on withdrawal have been inconsistent (

20,

26–28). However, direct comparisons are lacking for the timing and severity of new episodes following rapid or gradual discontinuation of antidepressants or as a function of drug exposure or elimination half-life or of clinical indications or diagnosis.

Method

Patients

We analyzed information from systematic clinical assessments of adult patients with a recurrent major affective disorder or panic disorder based on diagnostic criteria updated to DSM-IV-TR. All patients included in the study had responded well to antidepressant treatment and were evaluated, treated, and followed at the Lucio Bini Mood Disorders Center affiliated with the University of Cagliari in Sardinia. Diagnostic and assessment methods have been reported previously (

29,

30). We excluded patients who were even moderately clinically depressed, anxious, or hypomanic at the time of medication discontinuation as well as those whose rate of discontinuation was uncertain (22.3% of potential antidepressant-treated candidates). For the present analyses, consecutive patients were included who met the following criteria: diagnosed clinically with DSM-based recurrent major depressive disorder, bipolar I or II disorder, or panic disorder; received a tricyclic antidepressant (or the tricyclic-like tetracyclics maprotiline and mianserin), a modern antidepressant (serotonin reuptake inhibitors or bupropion, duloxetine, or venlafaxine), or more than one antidepressant, with or without a mood stabilizer, following standard clinical practices regarding drug selection and dosing in the study community; recovered from an antidepressant-treated index episode of a major depression or panic disorder, based on clinical euthymia and a score ≤7 on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D;

31) sustained for at least 30 days (including patients with panic disorder evaluated with the same rating scale for consistency); discontinued medication electively for clinical or personal reasons over a known period of time, allowing categorization into groups based on rapid (1–7 days) or gradual (≥2 weeks) discontinuation (none of the patients were tapered off antidepressants in the 8- to 14-day range); remained clinically stable or euthymic for at least 1 week after discontinuing treatment; and remained under prospective observation for at least 1 year, during initial treatment and through a first new episode of major depression or panic disorder that met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria at clinical assessment. Follow-up was censored at 100 months, based on the likelihood that discontinuation pace would exert little effect after the first few months (

21–

25).

All patients underwent initial diagnostic assessments, treatment, and follow-up evaluations by the same mood disorders expert (L.T.), based on semistructured interviews that followed the mood disorder components of the Research Diagnostic Criteria and Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV research assessment procedures (

30), as well as extensive follow-up clinical assessments and repeated assessments with standard mood disorder rating scales during systematic prospective follow-up every 2–4 months. Diagnoses were updated to meet DSM-IV-TR criteria in 2008 and 2009.

Patients provided written informed consent for analyses presented anonymously in aggregate form. The project database and data management comply with U.S. federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations pertaining to confidentiality of patient records, and research use of the database for this study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the District 8 Health Agency of Cagliari (Azienda Sanitaria Locale-8), Sardinia, as well as the Investigations Review Board of McLean Hospital, Belmont, Mass. Required data were entered into a database (by C.G., B.L., and L.T.) in coded form to protect patient identity.

Treatment

Treatment was determined clinically and included use of standard antidepressants, alone or with mood stabilizers (lithium carbonate or anticonvulsants that have received regulatory approval), atypical antipsychotics, or sedative-anxiolytic benzodiazepines as adjunctive medications. Use of such adjunctive treatments typically indicates greater clinical severity or lack of adequate response to antidepressant monotherapy (

32). Among study patients, adjunctive psychotropic medications were continued unchanged after discontinuation of antidepressants. We standardized antidepressant dosages (total mg/day) based on the relative potency (ratio of median manufacturer-recommended doses) of the various agents (

32), modified by median daily doses of specific antidepressants based on experience with nearly 2,000 patients with major depression treated at the study center so as to reflect local practice, to provide total imipramine equivalents in milligrams per day, including the sum of individual antidepressants when more than one were given simultaneously. We also considered the manufacturer-reported approximate elimination half-life of each antidepressant as a predictor of time to new episodes, using the longest elimination half-life when more than one antidepressant was used, or of a major active metabolite if its half-life differed substantially from that of the parent agent (e.g., norfluoxetine from fluoxetine) (

32). In cases involving more than one course of antidepressant treatment, only data from the most recent trial were considered.

Data Analysis

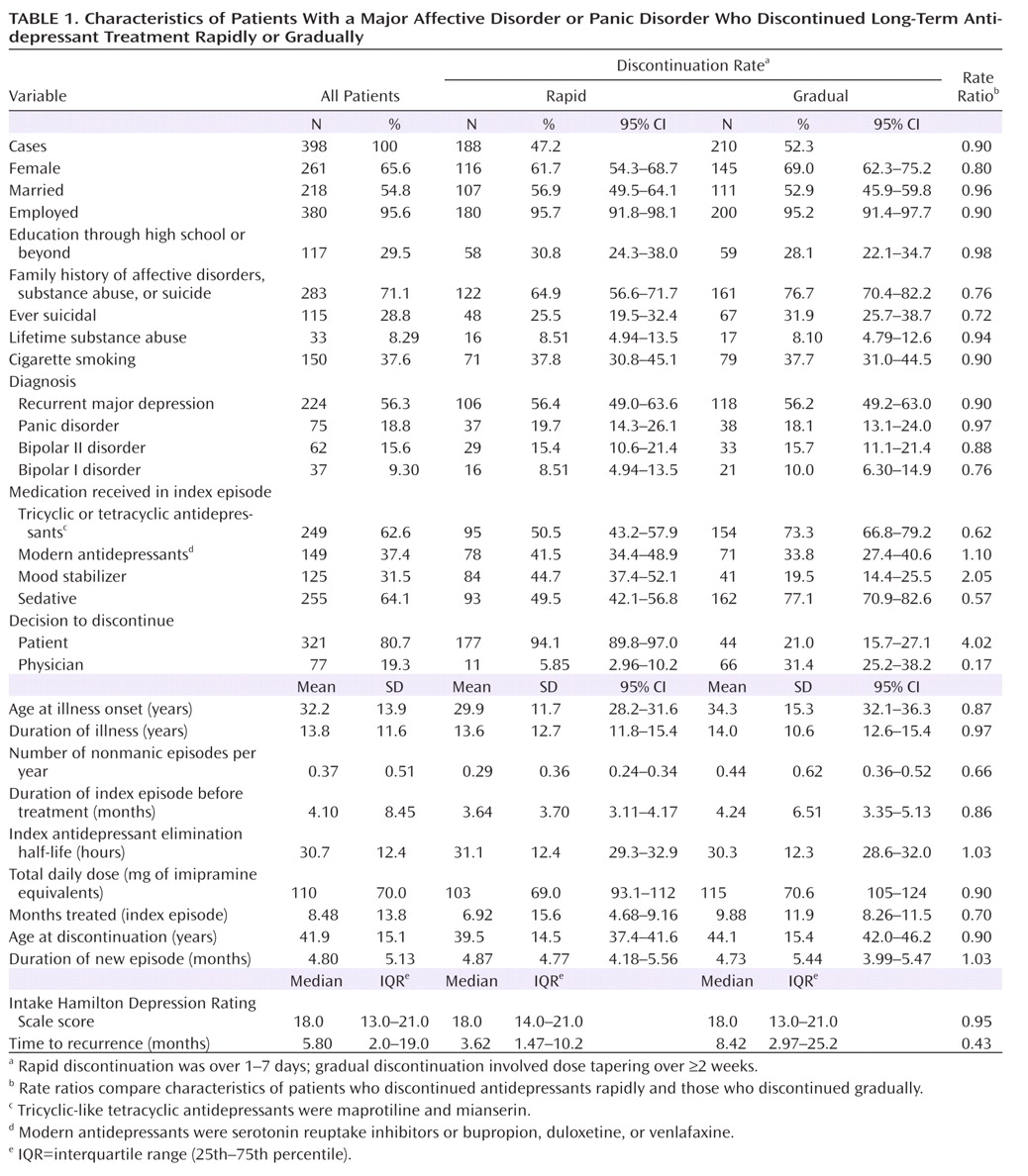

We compared demographic and clinical factors, selected a priori, between patients who discontinued antidepressant treatment abruptly or rapidly (1–7 days) and those who discontinued gradually (≥2 weeks). Factors considered included sex, family history of any psychiatric disorder (including substance abuse or suicide attempt), education level, marital status, current employment status, history of a substance use disorder, age at illness onset, total duration of illness, number of prior nonmanic episodes per year, approximate average time between the end of one episode and the start of the next, duration of the index episode of depression or panic, total HAM-D score, types of antidepressants received, total estimated dosages (in imipramine equivalents) of antidepressants received, approximate half-lives of antidepressants received, use of adjunctive psychotropic agents, duration of index antidepressant treatment, age at antidepressant discontinuation, and whether the decision to discontinue was made by the patient or by the treating physician (L.T.). The primary outcome measure was time to first new episode of a DSM-IV major depressive or panic episode, dated from the last day of antidepressant treatment.

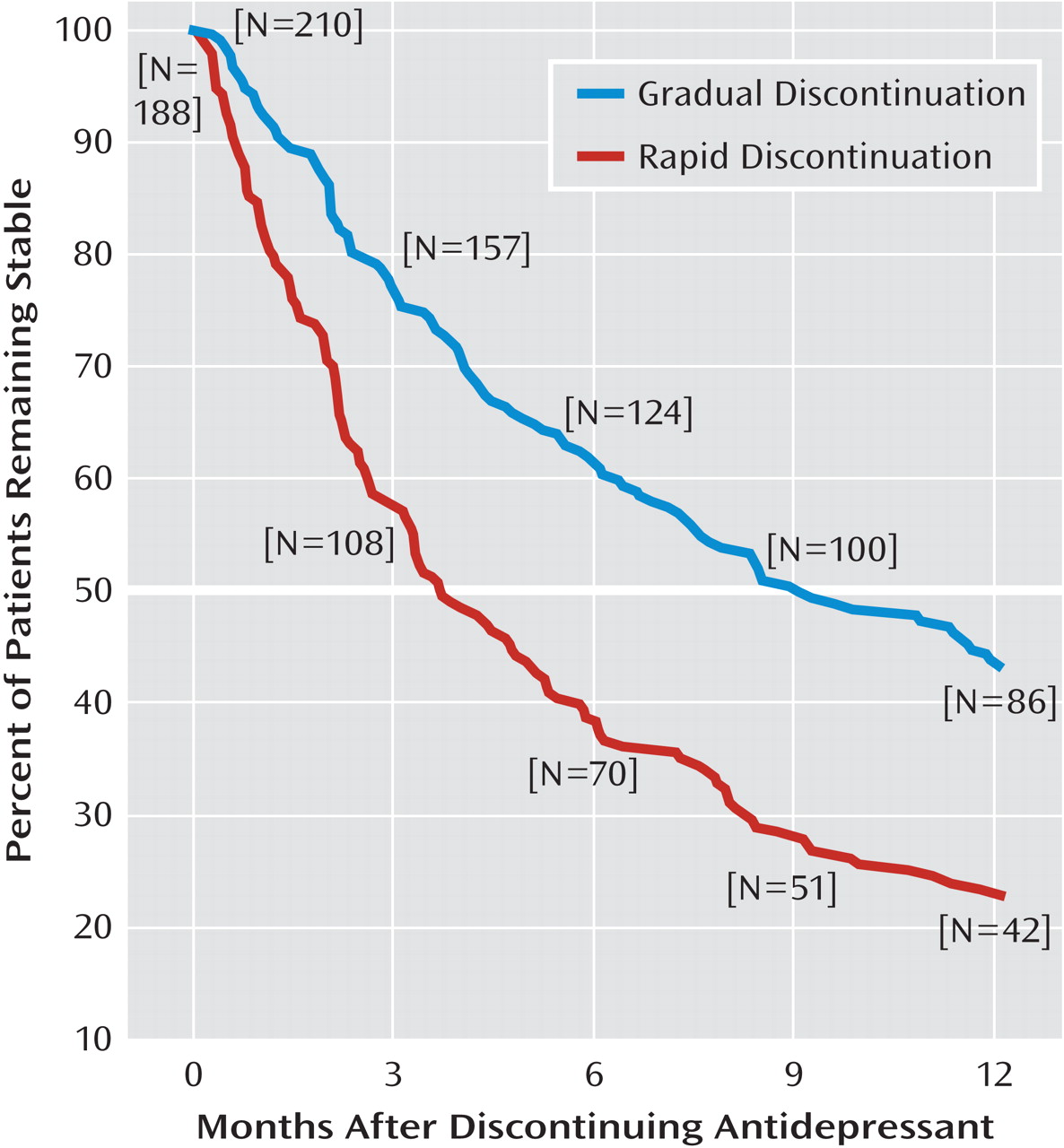

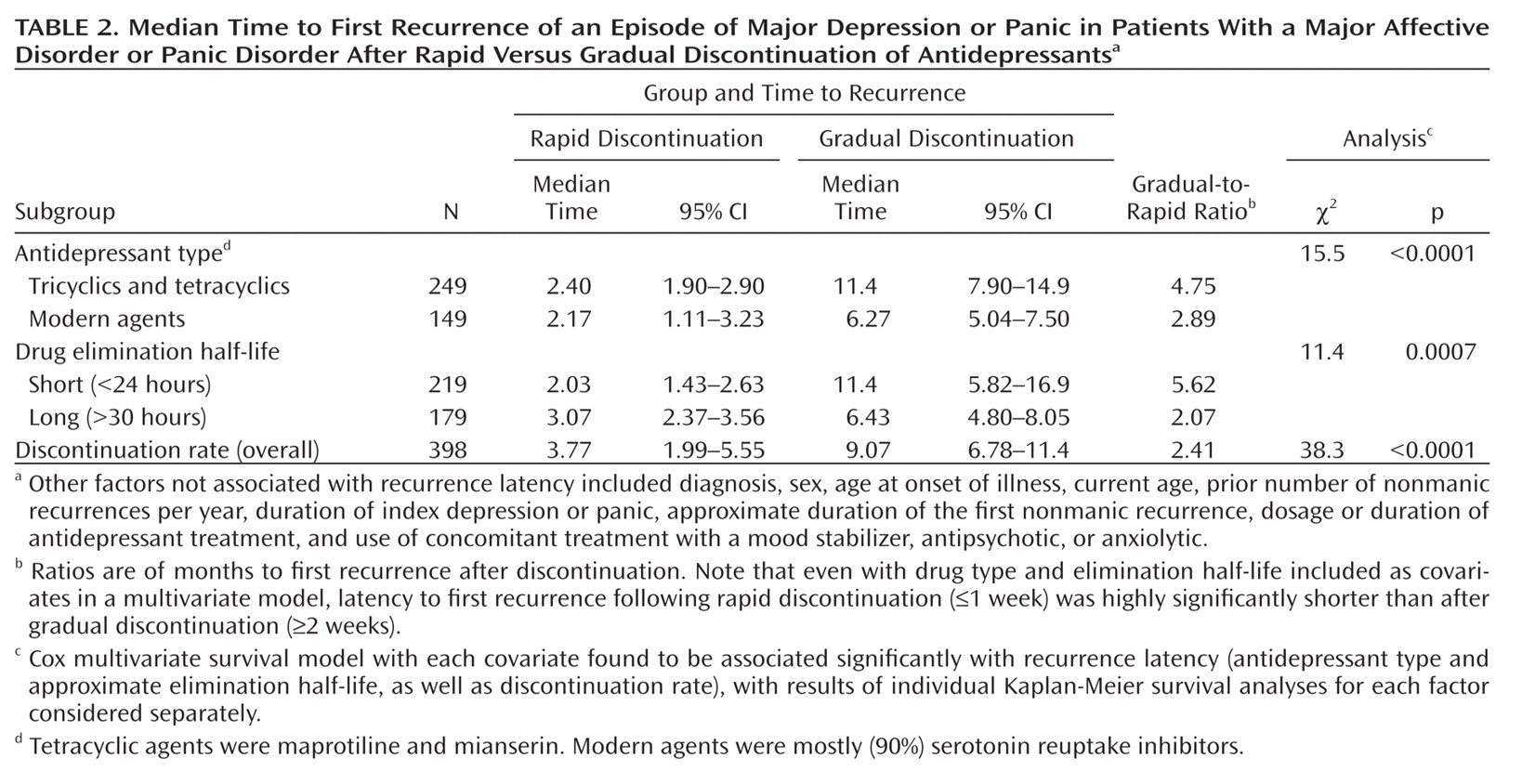

We compared characteristics of patients undergoing rapid versus gradual discontinuation of antidepressants, using analysis of variance methods for continuous measures and contingency tables for categorical measures. We used Kaplan-Meier survival analysis to estimate latency to a first new episode of depression or panic, with Cox modeling of covariates associated with time to relapse or recurrence, using the Mantel-Cox log-rank test with both methods. Differences between patients who discontinued rapidly and those who discontinued gradually were also compared as rate ratios. Statistical analyses were conducted with Statview, version 5 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.), and Stata, version 8 (StataCorp, College Station, Tex.). The primary hypothesis tested was that latency to first new illness would be shorter after abrupt or rapid discontinuation than after gradual discontinuation.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare clinical outcomes after discontinuing various antidepressants at different rates under closely comparable conditions of observation in patients with a range of major affective or anxiety disorders that were treated effectively with antidepressants long term, with or without a mood stabilizer. Previous efforts to make such comparisons across studies and sites yielded inconclusive findings, owing mainly to a lack of observations of differing discontinuation paces under the same conditions of observation, including switching from antidepressant treatment to placebo in experimental trials without randomization by rate of dose tapering (

1).

The principal finding of this study was that abrupt or rapid discontinuation of clinically effective antidepressant treatment was associated with a significantly shorter time to a first new episode of major depression or panic. Patients who discontinued rapidly were similar to those who discontinued gradually in most demographic and clinical characteristics, including factors associated with more severe illness (such as recurrence rate, duration of index illness, and use of adjunctive psychotropic medications), as well as pharmacotherapeutic factors (including index antidepressant exposure by drug type, dosage, and duration of treatment). Moreover, rapid antidepressant discontinuation remained associated with shorter time to first new illness even with Cox multivariate survival modeling to adjust for other potentially relevant covariates, and latency to illness was about one-fifth the average estimated interepisode time for the same patients before the index treatment (16.6 months compared with 3.62 months).

These findings add to previous evidence that rapid discontinuation of lithium in patients with bipolar disorder (

24,

25) and antipsychotic drugs in patients with schizophrenia (

23) was strongly associated with earlier, and often severe, new episodes of the primary illness being treated, arising within weeks or months, at intervals much shorter than predicted by the natural history of the untreated illnesses in general or previously in the same patients. Overall, the findings indicate that discontinuing various types of psychotropic medications abruptly or rapidly—whether by clinical decision on the part of patients or clinicians or by experimental design—can present substantial clinical and ethical problems.

We have hypothesized that illness following discontinuation of psychotropic drugs represents a response to long-term physiological adaptation of cerebral neural systems to the pharmacodynamic actions of the agents involved (

21). It is important to emphasize that the phenomenon of postdiscontinuation illness risk for specific disorders evidently is not the same as the complex of physiological, autonomic, and sensory responses often observed in the first days after discontinuing antidepressants, particularly short-acting serotonergic antidepressants (

13–

18,

20). Typically, such reactions arise early (within days), are transient, and may represent manifestations of drug withdrawal effects. It may be of some theoretical importance, as has been noted previously (

1,

33), that illness latency after discontinuing antidepressants has not been found to be related to duration of treatment (averaging more than 8.5 months in the present study) or dose. Occurrences of major depressive disorder or panic disorder and physiological drug withdrawal reactions may well arise from dissimilar mechanisms yet to be identified.

In this study, latency to a new illness episode after rapid discontinuation of antidepressants differed by less than 1 week for the two major classes of antidepressants (2.4 months for tricyclics and tetracyclics and 2.2 months for modern agents), whereas latency following gradual discontinuation was 5 months longer after discontinuing tricyclics or tetracyclics than after discontinuing modern antidepressants (11.4 months compared with 6.3 months; Table 2). In addition, illness latency differed more by discontinuation pace with agents that had relatively short elimination half-lives, whereas with both tricyclics and modern drugs, and with agents with short and long half-lives, latency to new illness was similarly short after rapid discontinuation (2–3 months; Table 2). Gradual dose tapering may be relatively more effective in countering risks of discontinuing older agents and those with short half-lives, although physiological discontinuation reactions are especially strongly associated with modern serotonergic agents, particularly those with short half-lives (

10–

20). Despite possible differences among specific agents, we recommend generally that gradual discontinuation be preferred for antidepressants of all types whenever clinically feasible. Rapid discontinuation of antidepressants may be required clinically if a severe adverse medical or severe manic reaction should emerge. However, even in such circumstances, we encourage close clinical monitoring to limit the impact of potentially early or severe recurrences of illness.

Finally, even though diagnosis appeared to have little or no overall effect on survival functions, based on multivariate survival analysis, contrasts in illness latency appeared to differ somewhat by diagnosis. Among patients with bipolar I disorder and panic disorder, differences in illness latency between rapid and gradual antidepressant discontinuation were larger (3.1- to 4.6-fold) than among those with bipolar II disorder or recurrent major depressive disorder (2.4- to 2.5-fold). These findings require replication with larger samples as well as mechanistic explanation.

This study's strengths include a large sample of patients diagnosed with a range of disorders by modern diagnostic criteria for which antidepressant treatment is prevalent, with assessments, treatment, and follow-up provided by the same investigator under consistent conditions and involving different antidepressant drug types. A major limitation of the study design is the lack of randomized assignment to precisely scheduled options for controlled dose tapering and discontinuation pace. However, ethical and feasibility considerations encourage naturalistic designs for such studies, even though controlled, randomized, and prospective trials would be desirable. Other limitations of the study include uncontrolled, and often patient-determined, drug discontinuation pace, as well as the possibility that some patients reported inaccurate discontinuation times or became ill after loss to follow-up. We excluded patients who showed clinical evidence of even mild depressive or anxiety symptoms close to the time of drug discontinuation, as well as those who became hypomanic or manic during antidepressant treatment and those who later developed manic or hypomanic first illnesses, so that the study would focus specifically on effects of antidepressant discontinuation on depression and panic (both of which are major current indications for antidepressant treatment). Another potential source of artifacts is the pooling of data collected over four decades, during which the popularity of tricyclic and tetracyclic antidepressants diminished and rapid discontinuation was increasingly discouraged. Nevertheless, a similar impact of the rate of antidepressant discontinuation was found among patients who discontinued in the 1975–1994 period (a twofold difference between gradual and rapid discontinuation) as well as among those who discontinued in the 1995–2008 period (a 1.75-fold difference).

The findings of this study include both clinical and research implications. First, with elective discontinuation of any type of antidepressant, gradual dose tapering appears to delay—and possibly to reduce—the risk of new illness, as evidenced by sustained separation of risk-by-time functions. The benefit of gradual discontinuation appeared to be greater with the older than the newer antidepressants, but latency to new illness was similar with all antidepressant types. These findings underscore the importance of warning patients that abrupt discontinuation of antidepressant treatment can lead not only to early adverse physiological (withdrawal) responses but also, over several months, to a return of the illness being treated. Primary care physicians, who prescribe most of the antidepressants used in the United States (

8,

9), should be aware that the risks associated with discontinuation of antidepressants appear to be determined importantly by rates of dose tapering and discontinuation. Moreover, since patients often make their own decisions about stopping drugs without seeking (or in spite of) medical advice, they should be warned at the start of antidepressant treatment of the potential consequences of unsupervised, especially abrupt or rapid, discontinuation. It is important to emphasize that postdiscontinuation illnesses appear to arise much earlier than would be predicted by previous illness cycles in the same patients, as we found previously with lithium in bipolar disorder (

25,

34) and antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia (

23). A specific circumstance in which abrupt or rapid discontinuation of antidepressants or other psychotropic medication is prevalent is pregnancy, with a high risk of recurrences and uncertain but possibly adverse effects on the fetus (

35,

36). In addition to these clinical considerations, the phenomenon of posttreatment discontinuation illness risk is very likely to confound the design, conduct, and interpretation of treatment trials based on comparing continued and discontinued treatment, especially in long-term trials that involve transitions from active treatment to placebo and among incompletely recovered patients (

21,

32).