Increasing evidence supports the existence of a spectrum of bipolar disorder far wider than acknowledged by current diagnostic nosology. While recent lifetime prevalence estimates indicate that 1% of the U.S. population meet DSM-IV criteria for bipolar I disorder and 1.1% for bipolar II disorder, recurrent hypomania without depression or recurrent subthreshold hypomania (with or without depression) was found in 2.4% of respondents in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (

1). These findings are consistent with those of other general population surveys conducted over the past two decades demonstrating the high prevalence of subthreshold bipolar symptoms and disorder based on a range of definitions (

2–6) and underscore the importance of unrecognized bipolarity in the general population.

The substantial proportion of the bipolar spectrum that is undetected has been attributed to both the narrow diagnostic criteria for bipolar II disorder and the inherent difficulty in detecting milder forms of hypomania (

7). This problem is potentially greatest for major depressive disorder, which may include heterogeneous conditions. Clinical studies indicate that 30%–55% of those with major depression may have symptoms of hypomania (

8–13) and that those with subthreshold hypomania are less likely to respond adequately to usual treatments for major depression (

14,

15). Investigations of community samples demonstrate that those with major depression and sub-threshold bipolar disorder have more frequent suicide attempts (

2,

16), higher rates of bipolar disorder among family members (

2,

6), and greater comorbidity with anxiety, impulse control, and substance use disorders (

2,

4,

6) than those without subthreshold hypomania. Some of the most compelling evidence for the validity of characterizing subthreshold mania is the greater conversion rate to threshold-level bipolar disorder among adolescents with subthreshold mania followed prospectively over time (

6). These findings provide strong support for the clinical significance of hypomania involving fewer symptoms or lasting for a shorter time than required for DSM-IV diagnosis.

Recognition of the full spectrum of bipolar disorders is dependent on identification of the most appropriate definitions for subthreshold manifestations. Previous descriptions by Akiskal and colleagues (

7,

17,

18) of the “soft” bipolar spectrum have proposed broadening criteria for bipolar II disorder as well as creating a third bipolar category to more fully acknowledge cyclothymic and hyperthymic states, family history of bipolar disorder, temperament, and hypomanic episodes that occur during pharmacotherapy. However, empirical evidence for either treatment-induced mania (

19) or a latent hypomanic temperament has not been forthcoming (

20). Based on emerging evidence for a dimensional conceptualization of hypomanic symptoms, inclusion of a diagnostic specifier for “hidden” bipolarity in major depressive disorder has been proposed (

21).

Using data from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R; 22), we examined the validity of distinguishing subthreshold hypomania symptoms in patients with major depression. We compared indices of clinical severity, family history, comorbidity patterns, and treatment utilization among patients with major depression with and without subthreshold hypomania. Particular focus was placed on comparisons between major depression with subthreshold hypomania, unrecognized by current nosology, and the two DSM-IV mood disorders for which clinical manifestations are most proximal: bipolar II disorder and unipolar major depressive disorder.

Method

NCS-R Sampling and Field Procedures

The NCS-R is a nationally representative face-to-face household survey of the prevalence and correlates of a wide range of DSM-IV mental disorders that was carried out between February 2001 and April 2003 (

22,

23). The sampling frame was English-speaking adults age 18 and older, selected through a multistage clustered area probability design from the civilian household population of the continental United States. The NCS-R procedures were approved by the Human Subjects Committees of Harvard Medical School and the University of Michigan. A detailed description of the survey's procedures is available elsewhere (

23).

The NCS-R interview was carried out in two parts. The part 1 interview was administered to a nationally representative household sample of 9,282 respondents (the response rate was 70.9%); informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to interview. Part 1 included the core mental disorders assessed in the survey along with a battery of sociodemographic variables. In an effort to reduce respondent burden and control study costs, part 2 was administered to 5,692 of the part 1 respondents, including all part 1 respondents with a lifetime core disorder plus a probability subsample of other respondents. The part 2 sample was weighted to adjust for differential probabilities of within-household selection, differential probabilities of selection from the part 1 sample into the part 2 sample based on part 1 responses, and discrepancies between the sample and the U.S. population on sociodemo-graphic and geographic factors assessed in the 2000 census. The part 2 sample was used for these analyses.

Mood Disorder Assessment

The NCS-R diagnoses are based on version 3.0 of the World Health Organization's Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI; 24), a fully structured, lay-administered diagnostic interview. Mood disorders (bipolar I disorder, bipolar II disorder, and unipolar depression) were diagnosed following the DSM-IV criteria, with the exception of the requirement that symptoms not meet the criteria for a mixed episode (criterion C for mania or hypomania and criterion B for major depressive episode). Criteria for subthreshold hypomania included the presence of at least one of the screening questions for mania (

1): “Some people have periods lasting several days or longer when they feel much more excited and full of energy than usual. Their minds go too fast. They talk a lot. They are very restless or unable to sit still and they sometimes do things that are unusual for them, such as driving too fast or spending too much money. Have you ever had a period like this lasting several days or longer?” or “Have you ever had a period lasting several days or longer when most of the time you were so irritable that you either started arguments, shouted at people, or hit people?” and failure to meet the full diagnostic criteria for hypomania. If respondents endorse either of these questions, the entire mania module of the CIDI is administered and they are queried about 15 symptoms of mania; those who endorse three or more symptoms are asked about the duration, age at onset, recurrence, frequency, severity, and impairment.

In this study, we characterized those with major depressive disorder according to the presence of the mania spectrum as follows: 1) major depressive disorder with mania (bipolar I disorder); 2) major depressive disorder with hypomania (bipolar II disorder); 3) major depressive disorder with subthreshold hypomania, as defined above; and 4) major depressive disorder alone. These categories and their corresponding definitions are presented in

Table 1. All cases in which there were plausible organic causes for these diagnoses were excluded. Clinical reappraisal interviews for bipolar disorders using the lifetime nonpatient version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID; 25) were conducted with a probability subsample of 50 NCS-R respondents. CIDI cases were oversampled and the data weighted for this oversampling. As described in more detail elsewhere (

26), concordance between the CIDI and the SCID was good for a diagnosis of bipolar I or bipolar II disorder (kappa=0.69), with sensitivity of 0.87, a specificity of 0.99, and an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.93. Concordance between the CIDI and the SCID was higher for bipolar I disorder (0.88) than for bipolar II disorder (0.50), but the McNemar test was consistently not significant, indicating that CIDI prevalence estimates were unbiased in relation to SCID prevalence estimates.

Age at onset, age at offset, and number of episodes of manic or hypomanic episodes and major depression were assessed using retrospective self-reports at the syndrome level. Course of illness was also assessed retrospectively by asking respondents to estimate the number of years in which they had at least one episode of mania or hypomania and the number of years in which they had an episode of major depression.

Symptom severity was assessed in 12-month cases using a self-report version of the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS; 27) for mania or hypomania and the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology–Self-Report (QIDS-SR; 28) for major depression. The YMRS was based on a fully structured respondent report version developed for parent reports (

29). Severity was assessed for the month in the past year when symptoms of either mania or depression were most severe. Standard YMRS and QIDS-SR cutoff points were used to define episodes as severe (including the original YMRS and QIDS-SR ratings of very severe, with scores ≥25 on the YMRS and ≥16 on the QIDS-SR), moderate (YMRS scores, 15–24; QIDS-SR scores, 11–15), mild (YMRS scores, 9–14; QIDSSR scores, 6–10), or not clinically significant (YMRS scores, 0–8; QIDS-SR scores, 0–5). We did not collect data on differences in the accuracy of recall for the 12 months used in this study compared with those of the QIDS-SR (30 days) and the revised YMRS (7 days).

Role impairment in 12-month cases was assessed using the Sheehan Disability Scale (

30). As with the YMRS and the QIDSSR, the Sheehan Disability Scale asks respondents to focus on the month in the past year when their manic, hypomanic, or major depressive symptoms were most severe. Respondents rated the degree to which the condition interfered with their home management, work, social life, and personal relationships using a visual analogue scale ranging from 0 to 10 (none=0, mild=1–3, moderate=4–6, severe=7–10).

Other Assessments

We also assessed anxiety disorders, impulse control disorders, and substance use disorders using the CIDI and based on DSMIV criteria. Organic exclusion rules and diagnostic hierarchy rules were used in making all diagnoses. As detailed elsewhere (

31,

32), blinded clinical reappraisal interviews using the nonpatient version of the SCID with a probability subsample of NCS-R respondents found generally good concordance between CIDI and DSM-IV diagnoses of anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders with independent clinical assessments. Diagnoses of impulse control disorders were not validated, as the SCID clinical reappraisal interviews did not include an assessment of these disorders.

Lifetime and 12-month treatment by health care professionals (including psychiatrists, other mental health professionals, and general medical providers), human services professionals, and complementary or alternative medicine providers was assessed by self-report. Information concerning mania in family members was collected in the mania section of the CIDI, and information about depression in family members was gathered only for the respondent's mother and father in the childhood section of the CIDI. Lifetime suicide attempts were assessed using the suicidality module of the CIDI.

Statistical Analyses

Because of the weighting and clustering used in the NCS-R design, all statistical analyses were performed using the Taylor series linearization method (

33), a design-based method implemented using SUDAAN, version 10 (RTI International, Research Triangle Park, N.C.). Significance tests of sets of coefficients were performed using Wald chi-square tests based on design-corrected coefficient variance-covariance matrices. Statistical significance was evaluated using a two-sided design with alpha set at 0.05. Controlling for respondent age and sex, linear regression was used to study the association between continuous outcomes (age at onset of mood disorders) and bipolar groups. Subgroup comparisons included major depression with mania versus hypomania versus subthreshold hypomania versus major depression alone. Logistic regression analyses were used to assess the associations between dichotomous outcomes and bipolar groups while controlling for age and sex.

Results

Table 2 presents the lifetime and 12-month prevalence rates for bipolar and unipolar mood disorders. When considered together, bipolar spectrum conditions were nearly as frequent as unipolar major depression without sub-threshold hypomania. The lifetime prevalence of major depression with subthreshold hypomania was 6.7%.

Information concerning clinical correlates of the mood disorder categories is presented in

Table 3. Individuals with bipolar II disorder were more likely than those with major depression plus subthreshold hypomania to have been treated for mood disorders over their lifetime as well as within the past 12 months, but no treatment differences were observed between the latter subgroup and the major depression alone subgroup. Compared to those with major depression alone, however, those with major depression with subthreshold hypomania had greater rates of comorbidity with anxiety, substance use disorders, and behavioral problems. In comparison to respondents with bipolar II disorder, those with major depression with sub-threshold hypomania had lower comorbidity. The proportion of respondents with major depression with sub-threshold hypomania who had suicide attempts (41%) fell between that of the bipolar II subgroup (50%) and that of the major depression alone subgroup (31%). However, these differences were not statistically significant.

Examination of clinical correlates within the bipolar spectrum (

Table 4) reveals that bipolar II disorder is associated with a fivefold higher risk of having a severe score on the YMRS compared to major depression with subthreshold hypomania, but no difference was observed when the categories of moderate and severe were collapsed. Individuals with major depression with subthreshold hypomania also were less likely to have been treated for manic symptoms over their lifetime or within the past 12 months. No difference was observed between these two conditions for family history of mania.

Clinical correlates related to depression are presented in

Table 5. Individuals with bipolar II disorder had significantly more severe depressive symptoms and more episodes of depression than those with major depression with subthreshold hypomania and were more likely to have been treated for depression over their lifetime. Those with major depression with subthreshold hypomania did not differ from those in the major depression only subgroup in severity of depressive symptoms, treatment of depression, or family history of depression. However, those with major depression with subthreshold hypomania had significantly more episodes of depression than those with major depression alone.

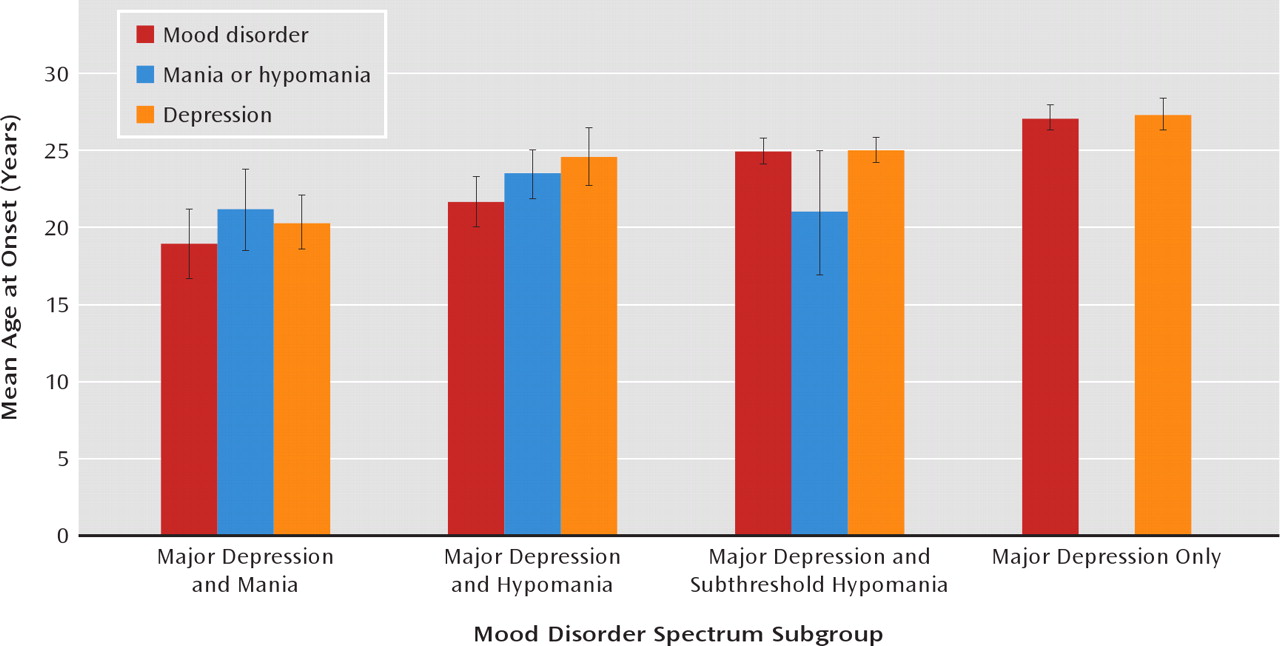

Figure 1 shows the mean age at onset of mania or hypomania and depression by bipolar spectrum subgroup. Major depression with subthreshold hypomania has an earlier age at onset than major depression alone and, in turn, a later age at onset than major depression with hypo-mania (bipolar II disorder). No differences were observed in age at onset of mania or hypomania and age at onset of depression between the major depression with hypomania subgroup and the major depression with subthreshold hypomania subgroup. The major depression with sub-threshold hypomania subgroup had a younger age at first onset of depression than did the major depression alone subgroup.

Discussion

Converging evidence from clinical and epidemiologic studies suggests that the current diagnostic criteria for bipolar II disorder fail to include milder but clinically significant bipolar syndromes and that a significant percentage of these conditions are diagnosed by default as unipolar major depression (

6,

16). Using data from a nationally representative sample, we examined the validity of characterizing subthreshold bipolarity as a source of heterogeneity in major depressive disorder (

6). Our principal aims were to estimate the prevalence of these categories of the bipolar spectrum and to compare the clinical characteristics of major depression with subthreshold hypomania to other bipolar disorders as well as to major depression alone.

Application of these categories revealed considerable diversity in the clinical manifestations of mood disorders and indicated that bipolar spectrum disorders occur almost as frequently as “pure” unipolar depression. However, the question of perhaps greatest importance to mood disorder research and clinical practice concerns the appropriateness of diagnosing major depression in individuals who also have subthreshold hypomania. This mood disorder subtype represents 39% of all cases of uni-polar major depression in the general population, and it was not found to differ from depression alone in terms of lifetime or 12-month treatment for mood disorders. While these findings are consistent with past research demonstrating that subthreshold hypomania is often subsumed under the category of unipolar depression (

8,

9,

11–13,

16,

18), important differences were nonetheless observed in the clinical characteristics of these categories. Individuals with major depression and subthreshold hypomania had a younger onset age, greater rates of comorbidity, more episodes of depression, and a trend toward more suicide attempts compared to individuals with major depression alone. Considered jointly with reported differences in response to pharmacotherapy between these forms of mood disorder (

15,

21), these findings underscore the heterogeneity of major depression and support the notion that a critical reappraisal of diagnostic criteria for mood disorders is warranted.

Differences were also observed for markers of clinical severity or history when comparing individuals with major depression and subthreshold hypomania and those meeting criteria for bipolar II disorder. However, these findings refiect the greater general illness severity in bipolar II disorder rather than differences in the basic expression of depressive or hypomanic syndromes. Perhaps the most convincing evidence for inclusion of the concept of subthreshold hypomania is the finding that a family history of mania is as common among those with subthreshold hypomania as those with mania/hypomania. Although the family history was based on respondent report, it is unlikely that there would be differential bias by the various mania or hypomania subgroups. As these differences are quantitative in nature, they are consistent with a conceptualization of depression with subthreshold hypomania as a milder manifestation of bipolar disorder as described nearly a century ago (

34), the pertinence of which has been reemphasized since the introduction of modern diagnostic systems (

8,

35). The inclusion of sub-threshold hypomania among those with major depression in the diagnosis of bipolar disorders would have a far-reaching impact on a number of scientific disciplines, ranging from descriptive and analytic epidemiology to genetic research, whose progress depends on the validity of mood disorder phenotypes. Most importantly, such an expansion of the bipolar concept would likely lead to important changes in the treatment of patients who are undiagnosed or misdiagnosed despite elevated morbidity and mortality rates (

36,

37).

These findings also have important clinical implications for the evaluation of mood disorders. If there is a substantial group of individuals with major depression who have hidden bipolarity, it would be critical to include careful evaluation of a history of hypomanic symptoms and a family history of mania, as proposed by the addition of a diagnostic specifier for subthreshold bipolarity in the diagnostic category of major depression (

21). Despite the widespread clinical belief that antidepressants may trigger bipolar symptoms in susceptible individuals, empirical evidence is lacking (

19). However, the addition of a mood stabilizer after response to antidepressant treatment may be beneficial in those who manifest sub-threshold bipolarity (

38).

These results provide the first comparisons of the prevalence and clinical correlates of bipolar II disorder, major depression with subthreshold hypomania, and major depression alone in a nationally representative U.S. sample. The high frequency of subthreshold hypo-mania among those with major depression confirm the findings of a population-based study of young adults that also revealed that approximately 40% of those with major depression may manifest bipolar disorder (

6). Some limitations of this study should be considered in interpreting the findings. The use of the fully structured, lay-administered CIDI precluded the collection of information on the full spectrum of expression of bipolar disorder proposed in recent studies (

7,

16,

39). Although we could not modify the thresholds for some of the diagnostic criteria for mania and depression, our definition of subthreshold bipolar disorder is still more restrictive than the definitions proposed by clinical researchers. Therefore, our prevalence estimate of subthreshold bipolar disorder is likely to underestimate bipolar spectrum disorder in the population. Although the clinical reappraisal study (

26) found good concordance of CIDI diagnoses with blinded clinical diagnoses based on the SCID, concordance was lower for bipolar II disorder and subthreshold bipolar disorder than for bipolar I disorder. The less flexible nature of the CIDI in comparison to clinical interviews could also have led to overestimation of comorbidity and potentially influenced clinical severity markers. Differences between the 1-year recall period of the symptom scales used in the present study and those for which the scales were standardized diminish the comparability of the present findings with those of previous clinical samples. In addition, the prevalence of mania in family members was not assessed in all groups. Finally, although the prevalence of bipolar disorder would be expected to increase if diagnostic criteria were expanded to include major depression with subthreshold mania, there would not be an increase in the overall prevalence of mood disorders because there would be a concomitant decrease in the rates of major depression. This risk should be examined critically but weighed against prospective evidence that youths with major depressive episodes plus subthreshold mania have a high probability of conversion to bipolar I disorder (

6) and that milder manifestations of the bipolar spectrum can be distinguished from major depression in severity, course, and comorbidity.