Internalizing problems such as anxiety and depression account for considerable public and personal burden across the lifespan. Developmentally, the common pattern is for anxiety to precede depression. Anxiety disorders are among the most common forms of mental disorder in early to middle childhood (

1,

2), and depression shows a dramatic increase around middle adolescence (

3,

4). Children and adolescents with anxiety disorders are at markedly elevated risk for the development of depression and other internalizing problems during adolescence and into early adulthood (

5,

6).

Emerging evidence is beginning to identify several risk factors that may be involved in childhood anxiety (

7). Twin studies point to a clear genetic risk in addition to contributions from shared and nonshared environmental factors (

8). Although specific phenotypes have not been identified, some evidence has pointed to key roles for emotional reactivity and arousal as basic processes that may increase risk for later disorder (

9,

10). These early characteristics are likely to increase risk for the emergence of certain temperaments that in turn predict later internalizing distress. Among the temperaments that have been most closely associated with anxiety disorders are a number of overlapping styles variously referred to as behavioral inhibition, social withdrawal, inhibition, and shyness (

11–13). Longitudinal research has demonstrated that toddlers or young children showing high levels of these temperaments (which we refer to as inhibition in this article) are at increased risk for later internalizing distress and, more specifically, anxiety disorders (

12,

14,

15).

Environmental risk for anxiety has been considerably more difficult to identify. A number of authors have argued for the importance of parental factors in childhood anxiety both through the influence of the parents' own anxiety and through parent-child interactions (

16–18). Given the limited variance accounted for by shared environmental factors in anxiety disorders as well as the extensive evidence for the importance of the child's temperament, most theories emphasize the role of reciprocal processes reflected in temperament-environment correlations and interactions. It is generally believed that early inhibited behaviors in the child elicit overprotective and controlling parental behavior (often augmented by the parents' own anxiety), which enhances the child's inhibition across development, ultimately increasing risk for anxiety disorders (

16,

17).

The elucidation of risk factors for anxiety disorders has begun to open prospects for early intervention and prevention of this high-frequency group of mental disorders (

19,

20). Despite the high societal burden of anxiety disorders, few attempts have been made to develop selective prevention programs. Selective interventions are those that reduce the risk of a disorder by targeting known risk factors (

21). It is possible that the dearth of such interventions is a result of the fact that models of environmental risk for anxiety have been developed only recently. One early trial failed to produce a significant reduction in temperamental inhibition after a 6-month intervention with preschool children and their parents, although the children's social competence and maternal control were successfully improved (

22). Slightly more promising findings were reported in a later trial in which parents of highly inhibited young children received a six-session intervention to help reduce their child's anxiety (

23). The intervention was designed to be brief and to be delivered in a group format to provide a minimally resource-intensive program with a real possibility for community application. Short-term effects at 12 months indicated that children of parents who received the intervention had slightly but significantly fewer anxiety disorders than children whose parents did not receive the intervention. These promising results provided the first indication that anxiety and other internalizing disorders might be preventable through early intervention.

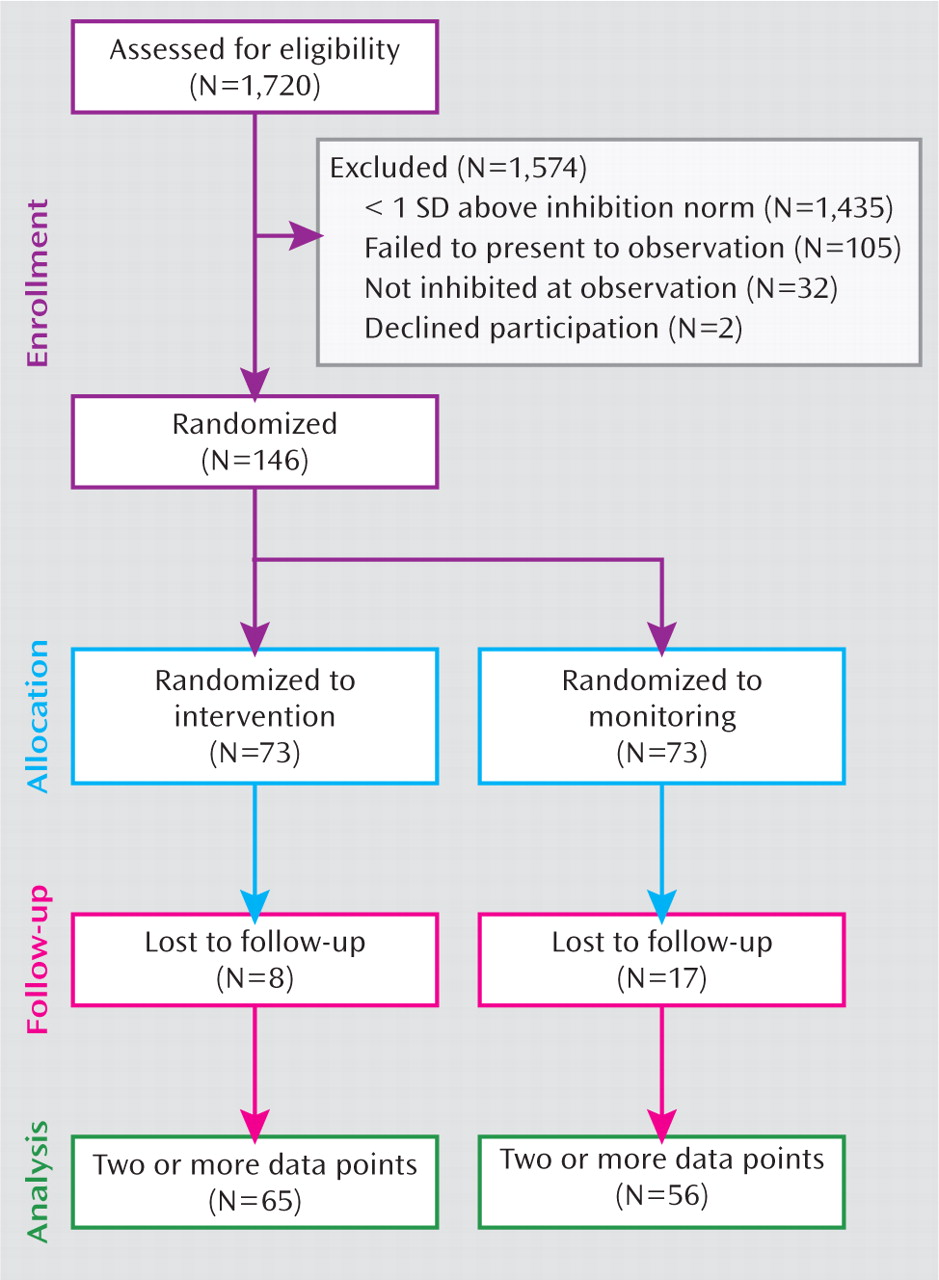

Here we describe the medium-term results of this early intervention program. The sample has now been assessed 3 years after the end of the program, as the children begin to enter middle childhood.

Results

The two groups that constituted the final sample did not differ significantly on any of the assessed demographic baseline measures, including the child's age and gender; the parents' ages, country of birth, and education level; and the number of children in the family. Descriptive sample data are presented in

Table 1. There were also no significant differences on baseline clinical measures, such as anxiety symptoms, inhibition, and number of disorders.

Diagnoses

Mixed-model analysis comparing the total number of anxiety disorder diagnoses across time between groups showed a significant main effect of time (F=44.45, df=3, 270.5, p<0.001) but no significant main effect of group. Notably, the group-by-time interaction was significant (F=2.97, df=3, 270.5, p=0.032). Follow-up comparisons of the interaction contrasts indicated a significant group-by-time effect from baseline to 12 months (t=2.16, df=254.3, p=0.032), from baseline to 24 months (t=2.22, df=272.8, p=0.027), and from baseline to 36 months (t=2.55, df=279.3, p=0.011). Estimated marginal means and standard deviations are presented in

Table 2. To provide a more clinically relevant indication, Table S1 in the online data supplement shows the percentage of children in each group who met criteria for the main anxiety disorders across time.

A similar analysis examining the average clinical severity of anxiety disorders indicated a significant main effect of time (F=16.06, df=3, 294.4, p<0.001) and a significant main effect of group (F=8.07, df=1, 121.7, p=0.005), which were qualified by a significant group-by-time interaction (F=5.17, df=3, 294.4, p=0.002). Follow-up comparisons indicated no significant group-by-time interaction contrast from baseline to 12 months but a significant group-by-time contrast from baseline to 24 months (t=3.83, df=297.3, p<0.001) and from baseline to 36 months (t=2.24, df=305.2, p=0.026).

Anxiety Symptoms

Mixed-model analyses comparing the groups over time on the mothers' reports of anxiety symptoms failed to demonstrate a significant main effect for group, although there was a significant group-by-time interaction (F=3.65, df=3, 246.5, p=0.013; the main effect for time was not relevant since scores were converted to standard scores at each assessment point). Follow-up comparisons indicated no significant group-by-time interaction contrast from baseline to 12 months, nor from baseline to 24 months, but a significant group-by-time effect from baseline to 36 months (t=2.66, df=247.9, p=0.008). To provide a more interpretable indication of the scores, nonstandardized scores are reported in Table S2 in the online data supplement.

Children's self-reports of anxiety symptoms on the Spence Children's Anxiety Scale at 36 months showed lower levels of reported anxiety symptoms in the intervention group relative to the monitoring group, although the difference fell short of statistical significance (t=1.99, df=63, p=0.051).

Temperament

Comparison of mothers' reports of the child's inhibition showed a significant main effect reduction over time (F=78.42, df=3, 272.1, p<0.001), but neither the group main effect nor the group-by-time interaction was significant. Similarly, fathers' reports of their child's inhibition showed a significant main effect reduction over time (F=34.20, df=3, 223.6, p<0.001), but neither the group main effect nor the group-by-time interaction was significant.

Comparison of total observed inhibition based on the laboratory observations failed to show a significant main effect of group or group-by-time interaction (the main effect for time was not relevant since scores were converted to standard scores at each assessment point).

Discussion

By the time they reached middle childhood, at-risk children whose parents had received a brief intervention when the children were at preschool age were significantly less likely to display anxiety disorders or report symptoms of anxiety than similar children whose parents had not received the intervention. These data constitute the first evidence that it is possible to produce lasting changes in children's anxiety symptoms after a simple intervention early in the child's life. The fact that the intervention was brief and conducted across groups of parents makes the results especially impressive. The format of the program is such that it allows relatively low-cost delivery in a variety of community settings, including preschools, parent-child centers, and health clinics. As a result, these data suggest that the program holds major public health implications.

The precise components or mechanisms of the program responsible for the effects are not known. The program was developed on the basis of models that point to key factors in the development of anxiety disorders, including inhibited temperament, parent anxiety, and parent over-protection (

17,

32). Interestingly, one of the key risk factors, the child's inhibition, was not specifically influenced by the intervention, although marked reductions were demonstrated in both groups. We previously showed that a slightly more intensive program applied with higher-risk children can produce reductions in inhibited temperament (

28), perhaps suggesting that the lack of effects in the present study were due to the reductions reported in the monitoring-only group. Nevertheless, we were unable to demonstrate differences between groups in this study, and therefore it does not appear that the preventive effects of this program are mediated through reductions in inhibition. Theoretically it has been suggested that one of the key distinctions between an inhibited temperament and anxiety disorder is the life interference associated with disorder (

33). In the present study we did not include a measure of life interference aside from the similar rating of clinical severity, which showed a clear reduction over time. However, in a later study, life interference from symptoms was shown to demonstrate marked reductions after a similar parent intervention (

28). Clearly, both theory and refinement of prevention programs would benefit from greater understanding of the mechanisms responsible for these effects.

The nature of the assessment of inhibition was focused primarily on social fears. In line with this bias, the majority of children met criteria for social phobia. The effects of the intervention also appeared strongest for social phobia and, to a lesser extent, generalized anxiety disorder. Little difference between groups was noted on separation anxiety or specific phobias, although this might be due to marked natural reductions over time on these disorders in this population. Future research might evaluate intervention effects on children selected on the basis of a more even balance of social and physical threat concerns.

It has been suggested that inhibited children head along a life trajectory of increasing risk for development of anxiety and related disorders (

19,

34). Genetic risk contributes to temperamental risk, which correlates and interacts with a variety of other risk factors, including parenting styles, parent psychopathology, peer interactions, and negative life events (

17,

34,

35). Consequently, it has been suggested that reducing risk to even a relatively small degree early in life may set the child on a new trajectory of reduced risk (

19). Despite the fact that it is unclear which risk factors were altered in the present study, the data are consistent with a picture of an altered trajectory. Differences between conditions were only minimally apparent at 12 months and appeared to show slightly larger effects with each passing year. Hence intervening at this particularly early key developmental period appears to have allowed a gradually increasing benefit to emerge.

At the final follow-up point in this study, children were still relatively young (around age 7), and hence the focus of the study was specifically on anxiety disorders, which are common in this age group (

2). The diagnostic interviews also assessed other internalizing disorders, such as depression and eating disorders, but the frequency of these disorders at this age was too low to be relevant. It is expected that with further development, differences between conditions may start to be seen on some of these other disorders. In particular, possible benefits of the program on major depressive episodes may begin to be noticed by midadolescence (

3,

4). If this occurs, it would add even more to the cost-benefit profile of the program, given the particularly high burden of depression (

36).

Applied studies always have a number of caveats and limitations, and several in the present study deserve consideration. The study was small by public health standards, and selection of participants was by convenience rather than by stratified population sampling. Our highly promising results now require replication in a larger representative sample of the population. Replication of the effects in disadvantaged populations and nonwhite ethnic groups is also essential. One major difficulty of a population-representative selection method in this case lay in the use of laboratory observations as a selection method. However, less than 18% of children who met inclusion criteria according to their mothers' reports of inhibition were ultimately excluded after laboratory observation. Hence larger studies could rely on maternal report for selection of participants without greatly sacrificing specificity. Clearly, the use of maternal report rather than laboratory observation would have a far greater community application. A large proportion of the results were also heavily influenced by maternal report. The fact that the main outcome measure, diagnostic interview, was determined by clinicians provides some additional confidence in the data, but the most powerful demonstration is the fact that by 36 months, the children themselves were reporting somewhat reduced anxiety symptoms. Nevertheless, future studies would benefit by including teacher and peer reports of anxiousness.

Early intervention for the prevention of anxiety and other internalizing disorders has lagged behind trials of prevention for externalizing disorders and social competence (

37,

38). Our data provide the first evidence that early intervention through parent education can provide a medium-term protection from anxiety disorders in middle childhood. The intervention is brief and relatively inexpensive, providing marked opportunities for use in the community. Whether these promising findings will translate to continued protection from anxiety later in the developmental trajectory and whether they can generalize to protection from related disorders remain exciting possibilities.