As of 2007, 35 million Americans, or 14% of the U.S. population, reported having abused opioid analgesics at some point in their lives (

1). In the same year, prescription opioids surpassed marijuana as the most common gateway to illicit drug abuse among adolescents, with approximately 9,000 Americans becoming new opioid abusers each day (

1). The increased abuse of prescription opioids has dramatically increased overdose rates (

2).

This explosion in opioid abuse reflects increased medical and dental prescription of opioids in response to historical undertreatment of pain and gross underestimation of addiction rates following chronic opioid use for pain. Opioids also became more accessible as a result of overdispensing for acute pain and because of multiple providers prescribing opioids without coordination of services for multiple painful conditions (

3). Patients who were routinely given a 2-week supply of short-acting opioids (e.g., hydrocodone) typically used a small portion and placed the surplus in the family medicine cabinet. Over 60% of adolescents abusing opioids obtain them from a family member (

2).

The case presented in the vignette illustrates the strongest predictor of opioid abuse-prior substance abuse. In contrast, rates of opioid addiction among patients receiving chronic opioid analgesic therapy without a history of substance abuse are very low, at 0.2% (

4). Another significant risk factor for opioid abuse is comorbid mental illness, with reported rates of 24% in United Kingdom mental health services (

5) and 21% in a Canadian community mental health survey (

6). Somatization is a particular risk factor (

7), as are being female and being young (

8).

To reduce morbidity and mortality while ensuring appropriate access to analgesics, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) initiated work in 2009 to establish a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy for opioids (

9), which may require prescribers to periodically train and recertify using an opioid medication guide. Other requirements may include physician-patient agreement forms, patient counseling about individual opioid medications, and documentation of distribution by pharmacies.

Detection and Assessment

Early identification is important in preventing complications of prescription opioid abuse. In the vignette, Mr. J's opioid abuse was detected through the observations and inquiries of an astute clinician, a positive urine drug screen, and a rapid and effective psychological intervention in a primary care setting. Opioid misuse can be revealed through interview, intake questionnaires, observation, family reports, and urine toxicology. A patient who provides vague, inconsistent, or incomplete information about his or her history or who has difficulty establishing trust and rapport with the interviewer may be hiding substance misuse. Acute opioid intoxication produces constricted pupils, slurred speech, itching, euphoria or agitation, dry mouth, drowsiness, and impaired judgment. Opioid withdrawal produces dysphoric mood, nausea or vomiting, muscle aches, runny nose, watery eyes, dilated pupils, goose bumps, sweating, diarrhea, yawning, fever, and insomnia. Given Mr. J's high acetaminophen intake (up to 6,000 mg daily), another route of detection could have been elevated liver transaminase levels, evidence of hepatotoxicity. The upper limit of daily dosing of combined hydrocodone/acetaminophen (5 mg/500 mg) is eight tablets daily because of acetaminophen-induced liver toxicity above 4,000 mg daily.

A variety of screening instruments are available. A review of self-report measures (

10) recommends the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (

11), and the Opioid Risk Tool (

12), and more comprehensive screening with the Drug Abuse Screening Test (

13) or the CAGE-AID (named as an acronym for “

cut

down,

annoyed,

guilty, and

eye opener,

adapted to

include

drugs”;

14). The UNCOPE (

15) is named as an acronym for six questions that assess problem drug use:

using more of a drug than intended,

neglect of responsibilities, considering

cutting down,

objections by others,

preoccupation with the drug, and using the drug to relieve negative

emotional states. Finally, the Drug and Alcohol Problem Assessment for Primary Care (

16) is computer based and self-administered, which may facilitate more honest responses among people addicted to pain medication.

Differentiating between opioid use disorder and pseudoaddiction has clear treatment implications for pain management and substance use treatment. Pseudoaddiction is opioid-seeking behavior for escalating or inadequately treated pain (

17). Pseudoaddiction resolves with adequate pain relief (not necessarily with opioids) and does not involve a maladaptive pattern of substance use that leads to clinically significant impairment or distress. A substance use disorder is characterized by compulsive drug taking not solely for pain control; it includes failure to fulfill major role obligations, recurrent use in hazardous situations, recurrent substance-related legal problems, and continued use despite persistent social, interpersonal, or health problems.

Mr. J met DSM-IV criteria for opioid dependence, including loss of control over opioid use, preoccupation with obtaining more despite the presence of adequate analgesia, and continued use despite physical, psychological, or social adverse consequences (

17–

19). Physical dependence alone does not constitute a substance use disorder. The rates of pseudoaddiction may be underestimated.

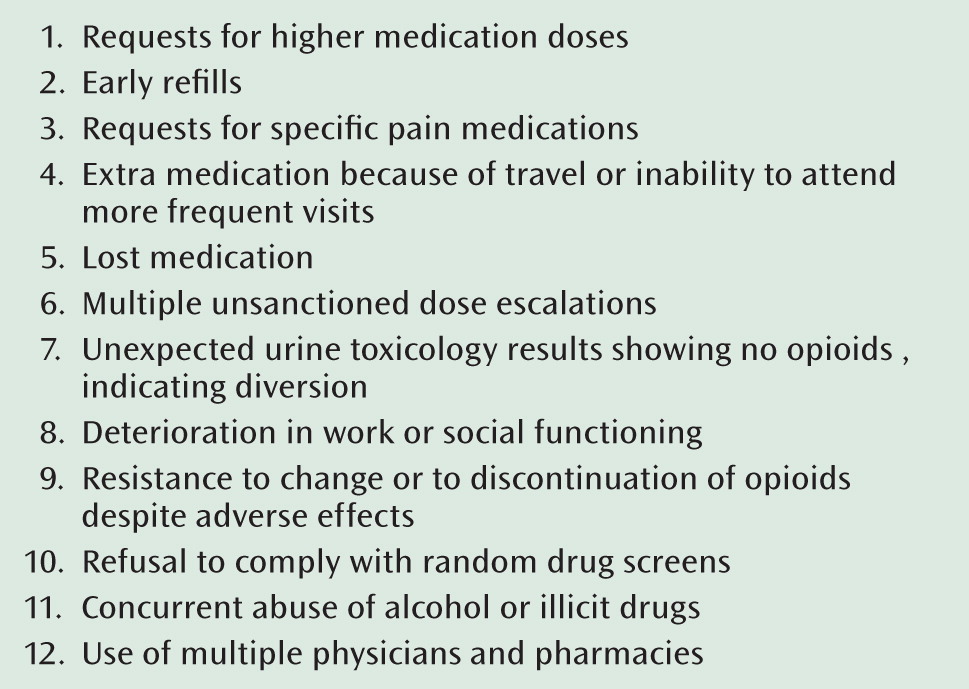

Aberrant medication-related behaviors (

Figure 1) can aid diagnosis. A single aberrant behavior is not evidence of abuse. For example, some patients may request more opioid medication or an alternative medication perceived as more potent, because some types of pain do not respond well to opioids (

21).

Treatment

The case of Mr. J illustrates common treatment issues in prescription opioid abusers: access to services, client engagement, choice of treatments, psychosocial problems, and pain management. As a result of these challenges, many outpatient providers decline to offer opioid addiction treatment. The psychiatrist's unease is often amplified when the patient reports chronic pain and states that only opioids have relieved the pain. Nevertheless, psychiatrists can treat such addictions effectively and address pain management. A helpful perspective is “to judge the treatment, not the patient” (

22). Ongoing assessment of functioning and of analgesia, monitoring for aberrant medication-related behaviors, regular pill counts, and regular urine drug screens can establish a correct diagnosis. Although analgesia may be insufficient, nonpharmacological pain management services can eventually eliminate the need for pharmacotherapy.

Access to Treatment and Providers

Increasing numbers of patients request specific medications, such as buprenorphine, which abusers learn about from the Internet and from contact with others who have sought treatment. Outpatient buprenorphine treatment is an innovation that may significantly reduce opioid use disorders and related morbidity and mortality, yet U.S. outpatient providers have been slow to adopt it (

23). The barriers cited by providers include lack of referral sources for counseling, the time required to obtain a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine (

24,

25), and limited organizational support (

26). Limited insurance coverage is also a barrier, although for veterans such as Mr. J in the vignette, coordinated multidisciplinary services are available that include full coverage for this pharmacotherapy (

27).

Pharmacological Options

Outpatient pharmacotherapies include buprenorphine, methadone, naltrexone, and medically supervised withdrawal. Selection from among these options depends on the goal (abstinence versus substitution), availability of methadone clinics, treatment history, and addiction severity (related to duration of use, dosage, and type of opioid used). Multiple studies confirm that methadone maintenance is the most effective treatment for suppressing use in the most highly dependent patients (

28,

29). Patients who require daily methadone doses exceeding 80–100 mg are unlikely to experience success with buprenorphine (

30,

31).

Patients frequently request buprenorphine as their first treatment because of its more convenient availability, flexibility in dosing, ease of discontinuation, and low abuse potential. Flexibility in the location of care and early opportunity for “take-home” medication in office-based buprenorphine treatment minimize stigma and improve adherence. This flexibility contrasts with the limited availability and substantial regulation in methadone maintenance programs. Buprenorphine's partial opioid agonist activity also produces a milder withdrawal syndrome than when other opioid medications are discontinued to attain abstinence (

32,

33). Buprenorphine also has demonstrated efficacy for reducing use of other drugs concurrently abused with opioids, such as cocaine (

34). Its diversion and intravenous abuse are reduced by using the combination of naloxone and buprenorphine; the naloxone leads to rapid onset of withdrawal in opioid addicts after intravenous administration but not sublingual administration, since sublingual naloxone is minimally absorbed and has no discernible clinical effect. Intravenous abuse of either buprenorphine or buprenorphine with naloxone is possible, but only in nonaddicted individuals, who instead experience modest euphoria from injecting either.

Prescribing buprenorphine requires that the physician obtain a Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) “DATA 2000 waiver” (based on the Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000, Title XXXV, Section 3502 of the Children's Health Act of 2000). This waiver requires training on treatment plans, goals, rules, and monitoring of urine and pill counts, backed by signatures on supporting documents. Clear protocols are used for the induction, stabilization, and maintenance stages.

Table 1 summarizes each treatment stage, buprenorphine/naloxone dosages, and visit frequency. The patient must experience at least mild withdrawal symptoms before beginning buprenorphine/naloxone treatment. Because of buprenorphine's stronger affinity for the μ-opioid receptor compared with other opioids, it will replace other opioids and cause immediate withdrawal if not administered when the patient is already in withdrawal. If the patient takes buprenorphine after starting to have withdrawal symptoms, it will relieve the symptoms. Handouts are available for patients on expectations regarding their buprenorphine treatment (e.g.,

www.naabt.org/education/what_bt_like.cfm).

Medically supervised withdrawal followed by nonpharmacological treatments can work for selected patients in some settings, such as in residential drug-free treatment programs, or when opioid access can be prevented through other means, such as naltrexone maintenance treatment. “Detoxification” alone, however, has a high relapse rate with a short time to relapse: one-third of patients return to opioid abuse within a week, 60% within a month, and over 80% within 6 months (

33,

35,

36).

Naltrexone treatment has substantial adherence challenges, and transitioning from opioid dependence to this antagonist is difficult. Patients need strong social supports to ensure observed oral ingestion of the naltrexone three times a week, and these supports for medication adherence benefit from strong negative contingencies (e.g., returning to prison for work-release parolees or loss of medical license for physicians). Depot naltrexone lasting 1 month can greatly reduce adherence problems. (In October 2010, the FDA approved an extended-release injectable formulation of naltrexone for use in treating opioid dependence.)

A recent review suggests caution in prescribing certain additional psychoactive medications along with buprenorphine, methadone, and naltrexone. Dangers include altered metabolism of either medication, methadone overdose, and opioid withdrawal syndromes. Awareness of these interactions is critical (

37).

Engagement

Immediate or same-day consultation is recommended to engage patients with alcohol or drug problems. Many patients are motivated for treatment but are ambivalent and have several false starts before engaging in treatment. Motivational interviewing addresses ambivalence to engage a patient in treatment through empathy and evocation of collaboration from the client. Rather than a stand-alone intervention, motivational interviewing is often combined with psychological interventions for pain management or relapse prevention. A meta-analysis of studies comparing motivational interviewing to no treatment revealed a 0.69 average effect size in favor of motivational interviewing (

38).

Behavioral Treatment

While no specific psychological intervention has been shown to be superior to others, the addition of any intervention to maintenance pharmacotherapy improves treatment retention and abstinence (

39). Relapse prevention, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and voucher- or monetary-based incentive programs are generally efficacious (

40). Specific approaches for opioid addiction include brief reinforcement-based therapy with contingency management (

40), as well as acceptance and commitment therapy (

41), which is also effective for chronic pain management (

42–

44).

Pain Management

Managing addiction with combined buprenorphine and naloxone offers opportunities for pain management because the combination's agonism at the mu opioid receptor may provide modest pain relief while its kappa antagonism minimizes hyperalgesia. However, this combination treatment might be inferior to higher-dosage opioids for pain relief because it is a partial agonist at the mu receptor. Buprenorphine analgesia diminishes above doses of 4 mg, and its analgesia lasts for approximately 8 hours per dose. Additional opioids will minimally enhance analgesia while a patient is taking buprenorphine with naloxone. Alternative pain management strategies may be required, such as activity modification, physical rehabilitation (e.g., gradually increased exercise, stretching), orthotic devices, other medications (e.g., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen), invasive procedures (e.g., surgical correction, nerve blocks, joint injections), biofeedback, and other behavioral interventions (e.g., distraction).

Regulatory Issues

Treating patients with comorbid addiction and chronic pain requires an understanding of the FDA rules about off-label use. Buprenorphine without naloxone is approved for treatment of opioid addiction, and in 2009, the FDA approved generic buprenorphine tablets for “supervised dosing” in pain management. Using this generic agent for pain treatment is legal, but providing it to opioid addicts is problematic. Buprenorphine alone has been diverted to abuse, and providing weeks of unsupervised outpatient doses to potential abusers, even those with chronic pain, will surely increase diversion, which could lead to rescheduling buprenorphine and the combination of buprenorphine and naloxone from DEA Schedule III to II. Such a change could lead to elimination of office-based buprenorphine maintenance treatment for addiction.

State prescription monitoring programs merge information about prescriptions and share it among prescribers and pharmacies to minimize diversion through doctor shopping. The 38 current prescription monitoring programs vary in scope of authority, in whether provider participation is voluntary or mandatory, in whether there are penalties for nonparticipation, and in who accesses database information. Because patient privacy regulations would likely prohibit VA participation in any state's prescription monitoring program, legislation is planned to address this limitation and to expand prescription monitoring programs to all states. Such actions should reduce buprenorphine diversion and protect this office-based addiction treatment.