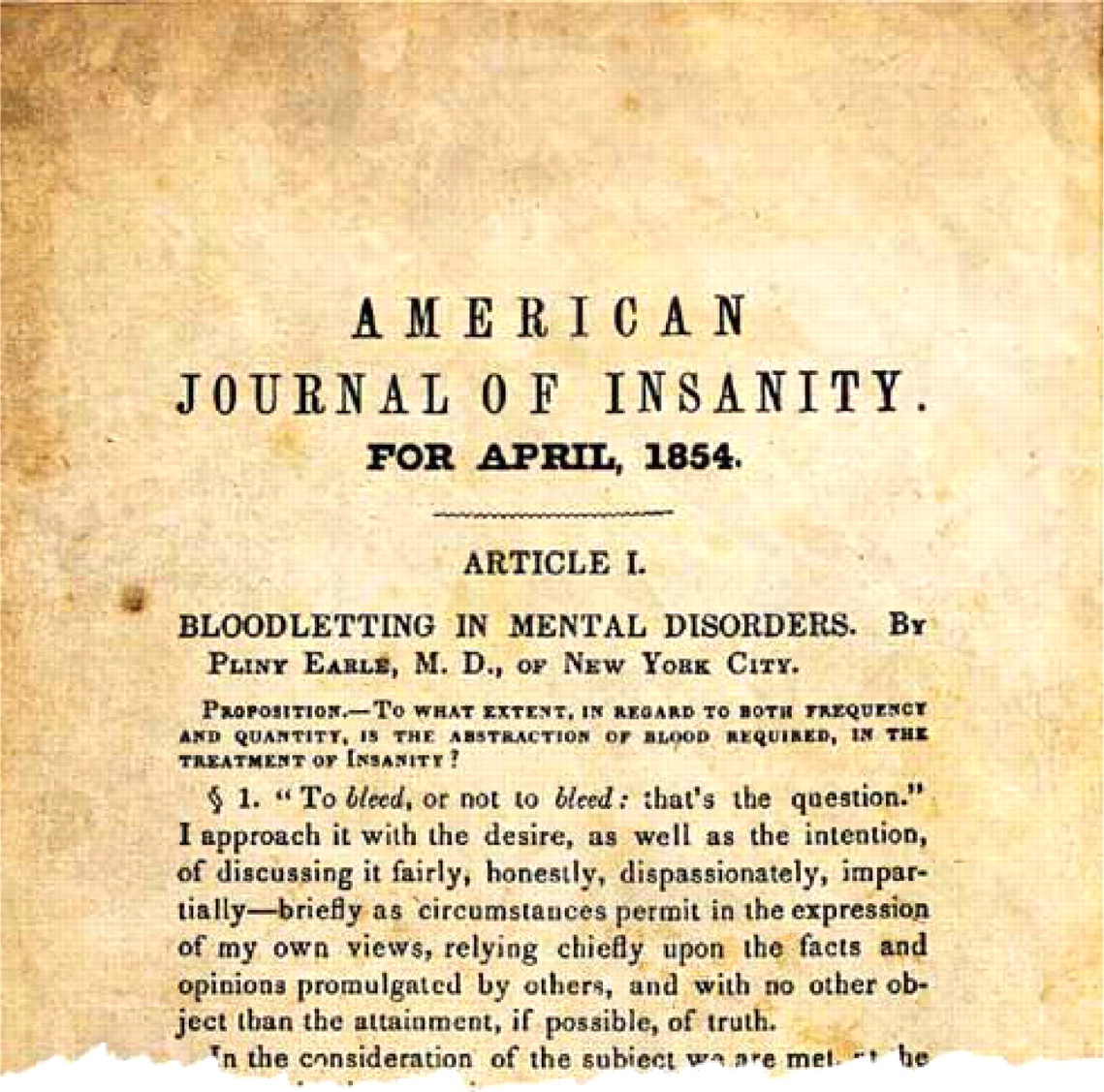

I sometimes peruse old AJP archived articles for some guidance, pearls of wisdom, or inspiration from early practitioners of our profession. I came across an April 1854 article in the American Journal of Insanity (forerunner of AJP) that made me feel much pride as a psychiatrist. The work, “Bloodletting in Mental Disorders” by Pliny Earle, M.D., is a 119-page article authored by one of the 13 superintendents of mental health facilities who were founders of the group that eventually evolved into the American Psychiatric Association. The article showed not just attention to the clinical aspects of the topic but also a sensitivity to the political and historical issues relating to it. I found myself trying to empathize with the perspective of the author, Dr. Earle.

The stage was set by 1854 with the historical impact of the iconic Benjamin Rush, who had advocated a broad, vigorous use of bloodletting despite the influence of a number of New England mental health institution superintendents who were critics of the practice. Dr. Earle started his article with a literary association: “To bleed, or not to bleed: that's the question.” He then proceeded to articulate opinions on the topic from over 100 clinicians, ranging from critics to advocates, and categorized nuances relative to practice, making subtle distinctions among the various viewpoints.

It is striking how delicate and diplomatic Dr. Earle was in showing respect for the memory of Benjamin Rush while expressing disagreement with Dr. Rush's advocacy of bloodletting. Dr. Earle artfully allowed that maybe the causes of some mental disorders were different during Dr. Rush's era, compared with the mid-19th century, and that that had led to different treatment practices. Dr. Earle, I believe, demonstrated skill as a leader trying to improve the treatment of mental health disorders while avoiding unnecessarily tarnishing the memory of Benjamin Rush, a founding father of the country and an esteemed physician who published the first textbook on mental illness in the United States.

Dr. Earle, with deference to his colleagues, reported his own findings from his facility in New York State at the close of the article. He presented data from 1845 to 1848 with an analysis of the treatment of 77 patients suffering from acute mental health problems. Bloodletting had been performed on four of the patients before admission to the facility, with fatal results. The overall data supported a trend toward a correlation between better treatment results and less use of bloodletting procedures.

Pliny Earle referred to his article as an essay, and this may have allowed him to be flexible in the manner in which he addressed bloodletting. He described sending the document to the printer in parts, with extracts collected incrementally as other parts went through the press. Dr. Earle reflected on the diversity of opinion noted in his article and expressed concern should he have miscategorized anyone's opinion. Dr. Earle demonstrated respectfulness to colleagues while being forceful and clear in his own expressed opinion. He was flexible and sensitive, not unnecessarily antagonizing colleagues who disagreed with his opinion. He communicated in a style that might allow dignity for physicians who would need to face that they had been committed to a harmful treatment practice. Dr. Earle showed a devotion to developing a consensus on the correct opinion involving bloodletting practices. In best working toward that goal, he also demonstrated the maturity to try to minimize inflaming the advocates of bloodletting.

We now take it for granted that bloodletting (phlebotomy) is not a legitimate medical treatment except for a few conditions, such as hemochromatosis and polycythemia. We can take pride in a colleague from an earlier era, Dr. Earle, for having nudged that understanding along with this 1854 journal article.