The Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness–Alzheimer's Disease study (CATIE-AD), funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, was designed to compare the effectiveness of antipsychotics and placebo in patients with Alzheimer's disease and psychosis or agitated/aggressive behavior (

16), and by design it included measures with which to investigate the cognitive effects of these medications. In contrast to many efficacy trials, CATIE-AD included outpatients in usual-care settings and assessed treatment effectiveness with a variety of outcomes over a 9-month intervention period. Initial CATIE-AD treatment (olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, or placebo) was randomized and double-blinded, yet the protocol allowed medication dosage adjustments or switching to a different treatment, based on the clinician's judgment. The primary CATIE-AD outcome measure was the time to discontinuation of the initially assigned medication for any reason (

17). This was intended as an overall measure of effectiveness that incorporated the judgments of patients, caregivers, and clinicians, reflecting therapeutic benefits in relation to undesirable effects.

In this article, we report the effects of time and of treatment on neuropsychological measures during the trial.

Method

CATIE-AD Study Design

The rationale and design of CATIE-AD have been described elsewhere (

16,

17). Briefly, the 36-week study period occurred in up to four possible phases for each patient. Phase 1 began at baseline, when 421 patients were randomly assigned, in a double-blind fashion, to receive olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, or placebo (randomized allocation ratio, 2:2:2:3). If the phase 1 medication was discontinued, the patient could enter phase 2 or open treatment (phase 4). In phase 2, if the patient had originally been assigned to receive an atypical antipsychotic, he or she was randomly assigned, in a double-blind fashion, to receive one of the other atypical antipsychotics or the antidepressant citalopram (randomization allocation ratio, 3:3:2). If the patient had originally been assigned to receive placebo, he or she would be randomly assigned to receive citalopram or an atypical antipsychotic (randomized allocation ratio, 3:1:1:1). Upon discontinuation of phase 2 medication, the patient could enter phase 3 and be randomly assigned to open-label treatment with an atypical antipsychotic not previously assigned. At any time, the clinician could choose to enter the patient into phase 4, where data collection continued but the physician prescribed medication.

To participate in the trial, patients had to meet DSM-IV criteria for dementia of the Alzheimer's type or the criteria for probable Alzheimer's disease from the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (

18); be ambulatory outpatients living at home or in an assisted-living facility; have an MMSE score in the range of 5–26; have had delusions, hallucinations, agitation, or aggression nearly every day over the previous week or intermittently over 4 weeks; have symptom ratings of at least moderate severity on the conceptual disorganization, suspiciousness, or hallucinatory behavior item of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS;

19) or ratings indicating at least weekly occurrence with moderate or greater severity on the delusion, hallucination, agitation, or aberrant motor behavior item of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (

20).

Patients were excluded if they were taking antidepressants or anticonvulsants for mood stabilization. Cholinesterase inhibitors were permitted. The study was reviewed and approved, and the informed consent was documented and approved, by the institutional review boards of each of the 42 study sites.

Present Study

In the present study, we assessed the weekly rate of change and the total change over 36 weeks on several measures of cognitive function. The study included all trial participants who did not report sedation at baseline, for whom data on years of education (a model covariate) were available, and for whom baseline measures and at least one follow-up measure of cognitive function were available. Eight patients reported sedation at the 12-week visit, and their scores for that visit were excluded from these analyses. Changes in cognitive function were assessed for the total group and for subgroups defined by randomized medication.

Cognitive Assessments

The following instruments were administered at baseline and at 12, 24, and 36 weeks: the MMSE; the cognitive subscale of the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS-Cog) (

21); three additional ADAS subscales—concentration/distractibility, number cancellation, and executive function (mazes) (

22); tests of category instances (semantic fluency and animal category) (

23); the finger tapping test, preferred and nonpreferred hand (

24); the Trail Making Test, Part A (Trails A;

25); and a measure of working memory deficit determined by the difference in the 10-second-delay and no-delay dot tests of visuospatial working memory (

26).

A cognitive summary score was calculated in a two-step process. First, the normalized z scores for each of the component measures (after recoding so that higher scores on each component test indicated higher functioning) were averaged. These averaged scores were then normalized. The z scores were computed using baseline means and standard deviations for each component score among all patients included in these analyses. The components of the summary score included the 11 components of the ADAS-Cog, the three additional ADAS subscales (concentration/distractibility, number cancellation, and executive function), the category instances tests, the mean of the scores for the preferred and the nonpreferred hand on the finger tapping test, the Trails A, and the working memory deficit. If more than four component scores were missing, the cognitive summary was considered missing.

In addition, Clinical Global Impression of Change (CGIC;

17) scores were collected. The CGIC is a seven-point scale of the clinician's assessment of the patient's change in mental status since study baseline, with a score of 1 indicating “very much improved,” a score of 4 indicating no change, and a score of 7 indicating “very much worse.” A physician-rated cognitive dysfunction factor of the BPRS (

27) consisting of the conceptual disorganization and disorientation items was calculated but was not included as part of the cognitive summary score.

Statistical Analysis

Mean cognitive scores at baseline were compared by categories of age, gender, years of education, and pooled study site using t tests or ANOVA as appropriate. The seven sites with 18 or more patients were not pooled; the 35 sites with fewer than 18 patients were pooled according to a predetermined algorithm into eight pooled sites (

17).

To accommodate longitudinal measures (multiple observations per patient over time) and the inherent within-patient correlations, mixed-effects linear regression models were used. These models assessed the rate of change (slope) in cognition over the trial period for each of the cognitive measures and the cognitive summary score, adjusting for age, gender, education, and pooled study site. Random effects were specified for the intercept and slope (time in study, in weeks).

In the first set of analyses, study treatment was not considered. The dependent variable was the cognitive function score, and the independent variables were the covariates and time (weeks) since baseline. The regression coefficient for the time variable estimated the average weekly rate of change in the cognitive measure.

Further analyses assessed effect modification on weekly rate of change in cognition by baseline level of MMSE score (<19 or ≥19, more severe versus mild impairment), baseline BPRS total score (≤27 or >27, median split on behavior severity), and study site size (<18 patients [pooled sites] or ≥18 patients [stand-alone sites]). Each cognitive measure was modeled as a function of the covariates, time (weeks) since baseline, and an interaction term of time since baseline by baseline MMSE group, BPRS group, or study site size group. The interaction term tested whether the rate of change (slope) in the cognitive score differed by baseline MMSE, BPRS, or study site size.

The second set of mixed-effects analyses assessed the effect of each treatment on the rate of change in cognitive function. Treatment was included, provided that the patient had been receiving the treatment (olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, or placebo) for at least 2 weeks before the cognitive assessment. Follow-up cognitive assessments on dates when the patient was in the open-choice phase (phase 4) or had been receiving the study medication for less than 2 weeks were not included in these analyses. Separate models were fitted for each cognitive variable. The independent variables included the covariates, treatment assignment, and time (weeks) since baseline. An additional interaction term of time since baseline by treatment tested whether the rate of cognitive change differed among patients on a specific study medication compared to those on placebo.

The third set of mixed-effects analyses was similar to the second except that all atypical antipsychotics were combined for comparison with placebo. This set included more cognitive testing dates than the second set because a patient on a combination of atypical antipsychotic medications during the 2 weeks before cognitive testing would be included here but excluded from the second set of models. In addition, we used the model estimates of weekly rates of change over the trial to estimate the change in cognitive function over the full 36-week study period by study group. Since the statistical tests are tests of slope over the full study period, whether changes are expressed per week or over 36 weeks makes no difference to the statistical significance.

Generalized estimating equations were used to estimate the average CGIC score by treatment group and test for differences from placebo for patients on study medication for at least 2 weeks prior to cognitive testing.

All data were analyzed using SAS for Windows, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.). All p values are two-sided.

Results

All 421 patients who received randomized treatment assignments were assessed by at least one of the cognitive measures at baseline. One patient who reported sedation at baseline and 16 patients who did not report years of education were excluded from the analyses. In addition, follow-up cognitive measures were not available for 47 patients, leaving 357; of these, 342 had at least one follow-up cognitive measure at 12 weeks, 320 had at least one follow-up measure at 24 weeks, and 307 had at least one follow-up measure at 36 weeks. The study sample was 46% male, with a mean age of 77.6 years and mean of 12.3 years of education (

Table 1); 64% were taking cholinesterase inhibitors.

Over the 36-week follow-up period, participants significantly declined on several measures of cognitive function (MMSE, ADAS-Cog, ADAS concentration/distractibility, ADAS number cancellation, category instances, both finger tapping tests, Trails A, and the cognitive summary) and on the BPRS cognitive factor (

Table 2). The models in

Table 2 can be used to predict test score changes for a patient with specified covariate values in this sample. For a man 77.6 years old (the sample mean) with 12.3 years of education (the sample mean) in the study site that pooled all of the sites with five or fewer patients, the model-estimated declines over 36 weeks were as follows: the MMSE score decreased from 15.6 to 13.2, the ADAS-Cog score worsened from 34.2 to 38.6, the cognitive summary decreased from –0.06 to –0.46, and the BPRS cognitive factor score worsened from 4.6 to 5.0.

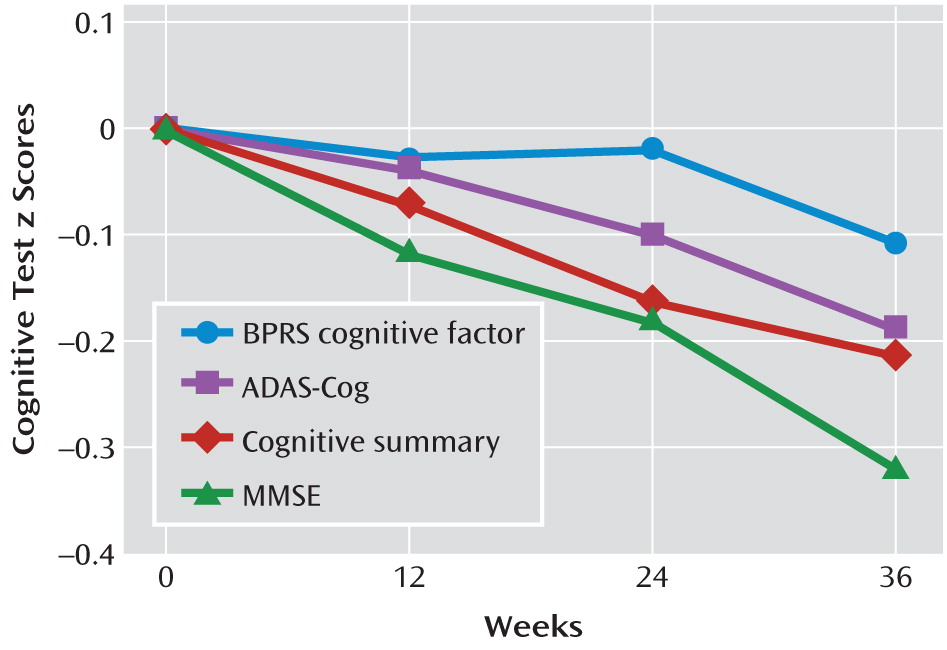

Figure 1, which includes both patients receiving atypical antipsychotics and those receiving placebo, shows that the declines in z scores for these tests over the 36-week study period were linear. It also shows that the normalized change in scores over time was more pronounced for the ADAS-Cog, the MMSE, and the cognitive summary than for the BPRS cognitive factor, which is more behaviorally related.

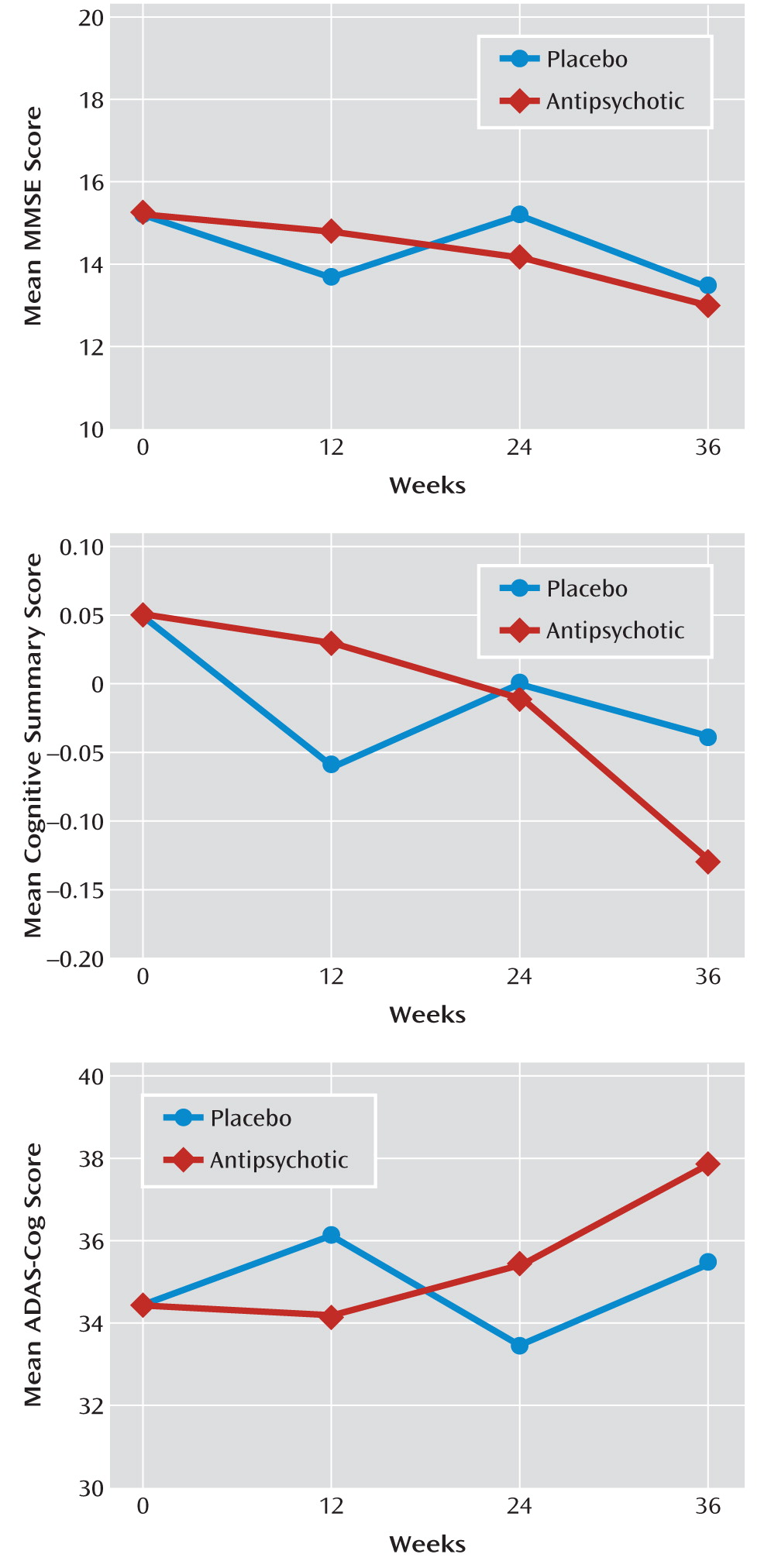

Figure 2 illustrates the changes in raw MMSE, ADAS-Cog, and cognitive summary scores over time for the full study population.

The rates of change in cognitive function did not significantly differ by baseline MMSE score (<19 or ≥19), BPRS total score (≤27 or >27), or study site size (<18 patients or ≥18 patients) (data not shown).

No significant differences were observed in the rates of change in most cognitive function measures between individual medication groups and placebo (

Table 2). However, on the cognition summary measure, patients receiving olanzapine or risperidone (for at least 2 weeks prior to assessment) had significantly greater rates of decline than patients given placebo. Compared with patients given placebo, significantly greater rates of cognitive decline were observed on the MMSE in patients receiving olanzapine, on the BPRS cognitive factor in patients receiving quetiapine, and on the cognitive summary in patients receiving olanzapine and risperidone.

Patients receiving any atypical antipsychotic (for at least 2 weeks prior to assessment) had significantly greater rates of decline in cognitive function as measured by the MMSE, the category instances tests, the cognitive summary, and the BPRS cognitive factor than did patients receiving placebo (

Table 3). On all cognitive measures, patients receiving atypical antipsychotics had lower scores than patients given placebo, although not all differences were statistically significant. The association between cognitive decline and atypical antipsychotic compared with placebo did not vary by baseline MMSE or BPRS score or by study site (data not shown), indicating that these variables exerted little or no effect modification.

The average CGIC score for patients receiving placebo was 3.13, indicating minimal improvement. The average CGIC scores for patients receiving atypical antipsychotics also indicated minimal improvement (3.11, 2.83, and 2.81 for olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone, respectively), and these changes did not differ significantly from that observed in patients receiving placebo.

Discussion

In our sample, Alzheimer's disease patients with behavioral disturbances showed a steady decline over 36 weeks in most cognitive areas, regardless of whether they received antipsychotic treatment or placebo. Over the study period, these declines were not only statistically significant but also clinically meaningful. The estimated rate of decline among placebo patients on the ADAS-Cog was similar to that seen in Alzheimer's patients without behavioral disturbances in other trials (

15,

28). Moreover, the rates of decline did not vary with initial level of cognitive impairment as indicated by baseline MMSE score. Our method of analysis used all data points from patients for whom data were available from baseline and at least one follow-up assessment. However, during the later assessments, there were fewer test scores mainly because of patients' inability to perform the tests or their dropout from the study, meaning that data cannot be assumed to be missing at random. Therefore, the cognitive decline over time is likely to be greater than documented in our study (

29).

We evaluated the effect of treatment with atypical antipsychotics on cognitive function by comparing the weekly change (the slope of the change in cognitive function over time) among patients who had been receiving their current medication (or placebo) for at least 2 weeks at the time of cognitive testing. For most cognitive tests, the rate of cognitive change did not significantly differ by antipsychotic agent. However, when the treatment groups were pooled, patients receiving antipsychotics had greater declines in cognitive function than did patients receiving placebo on all tests except the ADAS executive function subscale. Combining the active treatment groups provided greater statistical power, and many of the tests of cognitive function showed significantly greater rates of decline in patients receiving atypical antipsychotics compared to patients receiving placebo. Over the 36-week trial period, patients receiving any antipsychotic had an average decline 2.46 points greater on the MMSE than placebo patients, a difference both statistically significant (p=0.004) and clinically relevant.

In comparing the study medications to placebo, we limited our analysis to patients who had been taking the same drug for at least 2 weeks at the time of cognitive testing, essentially testing for a short-term effect. Alternatively, analyses could have been based on total exposure or exposure over some longer or lagged period. However, basing analyses on the sum of exposure over the trial would have mixed recent and distant exposures, possibly obscuring the short-term cognitive effect. Using a continuous exposure longer than 2 weeks would have substantially reduced the number of patients available for analysis since many patients switched medications after relatively short exposure periods. Decline in cognitive function may be one reason patients switch medication.

Because we did not measure differences in the rates of cognitive decline over longer exposure periods, we cannot address the question of whether these drugs would accelerate cognitive decline permanently or merely impair cognition during acute administration. It is also possible that this worsening of cognitive function with atypical antipsychotics would attenuate over time. We do not know whether the greater decline in cognitive function in patients receiving these medications was a worsening of Alzheimer's pathology or an independent effect. Sedation would be a possible explanation for decreased cognitive function among patients receiving these drugs, although we excluded data from all test days on which the patient's caregiver reported sedation. It is well known that antipsychotic medications degrade cognition in most nonpsychotic patient groups, such as when used for dyskinesia control in Tourette's syndrome, and have been shown to impair aspects of cognition in schizophrenia.

Although there is strong evidence for a detrimental effect of atypical antipsychotics on cognitive function (

8,

15), it is not clear whether this effect is equally strong in the different cognitive domains. The most significant effect that we observed when comparing individual drugs to placebo was in the cognitive summary score. Since this variable combines many of the other tests, it is less subject to random fluctuations, allowing differences between groups to be recognized. If significant effects were not found within a given cognitive domain, however, it may not be due to absence of effect but rather to insensitivity of the test. Patients receiving atypical antipsychotics improved overall clinically, as evidenced by CGIC scores; however, the improvements were not statistically different from those seen in the placebo group.

In addition to testing a variety of cognitive domains, this study had the strength of reflecting prescribing practices for the atypical antipsychotics most commonly used in Alzheimer's disease. The relatively small sample size, however, with patients spread over one placebo and three active medication arms, did not provide the statistical power to evaluate differences between the three drugs. Nevertheless, the differences between the active treatments tended to be smaller than those between active treatment and placebo.

Some early studies and meta-analyses conducted in nondemented patients with schizophrenia indicated that cognitive function may improve more in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics than in those treated with conventional antipsychotics (

9). Data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial, however, indicated that improvements in cognition with antipsychotic treatment were small and did not differ between atypical and conventional antipsychotics, leading the authors to conclude that they were likely due to the effects of expectation or practice (

30). Similarly, improvements in cognitive function reported (

12) for 104 patients with schizophrenia randomly assigned to receive either olanzapine or risperidone were consistent with the improvement due to practice effects seen in 84 healthy volunteers without schizophrenia. The fact that the Alzheimer's patients in the present study did not show cognitive improvement with treatment may be due to their overall declining cognitive function (as seen in the full study population), vulnerability to the deleterious cognitive effects of these medications, and the inability of these patients to benefit from the practice improvement seen in nondemented patients.

Individual trials in Alzheimer's patients generally report null effects of atypical antipsychotics on MMSE score, which often is the only cognitive measure used (

8). Meta-analysis of trials comparing olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, haloperidol, and aripiprazole to placebo over 6–26 weeks (

8), including 863 patients using olanzapine, quetiapine, or risperidone compared to 314 placebo patients, reported a weighted mean difference of 0.73 (p<0.0001) on the MMSE for drug compared with placebo, with poorer scores in drug group. In our study, the additional decline in MMSE score with risperidone compared to placebo was statistically significant, while the declines with olanzapine and quetiapine were not.

Other trials have assessed cognitive change in Alzheimer's patients using atypical antipsychotics. A randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 80 patients (

13) found greater declines in cognitive function (measured by the Severe Impairment Battery) in those receiving quetiapine than in those receiving placebo. A randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 268 Alzheimer's patients who did not have significant behavioral problems (

15) found greater declines on both the MMSE and the ADAS-Cog in patients receiving olanzapine than in those receiving placebo. Furthermore, the difference in ADAS-Cog scores was significant only in patients with lower baseline MMSE scores. In our study, we did not find differences in cognitive decline or treatment effect when patients were stratified by baseline MMSE score or baseline BPRS score.

In contrast, a retrospective chart review of 58 Alzheimer's patients treated with risperidone, olanzapine, or quetiapine (

31) found no decline in MMSE score in any of the drug groups. The patients in that study, however, tended to be younger and to have higher baseline MMSE scores than the patients in CATIE-AD. Moreover, the study required that patients take the medications for 6 months, and thus many patients who experienced negative cognitive effects would likely not have been included.

Our results provide additional broad evidence that, compared with placebo, atypical antipsychotics are associated with greater rates of decline in cognitive function in Alzheimer's patients with psychotic or aggressive behavior and that the magnitude of the additional declines is clinically relevant, reaching at least as great a magnitude as the effect of cholinesterase inhibitors but in the negative direction (

28). Furthermore, the results suggest that the declines in cognitive function span a range of cognitive domains, but given our sample size, we were unable to determine precisely the difference in effect by cognitive domain. Although our sample size was not sufficient to determine whether the rates of decline varied by atypical antipsychotic used, the declines were evident for all three medications compared to placebo. Despite the evidence for worsening cognitive function and other adverse events with antipsychotics, improvement in psychotic and aggressive behavior may still warrant use of these agents in individual cases (

17,

32). To aid in choosing the best medication for a given patient, the relative adverse effects on cognitive function within this class of medication need to be addressed in further studies that include assessments of attention, psychomotor function, and executive function.