After the acute phase of treatment for a first episode of psychotic illness, guidelines usually indicate that subsequent maintenance antipsychotic medication treatment should continue for at least 1 year, but consensus is lacking regarding the total duration of treatment if the patient remains asymptomatic (

1,

2). A 5-year observational study of patients with first-episode psychosis indicated that stopping antipsychotic medication increased the rate of relapse nearly fivefold compared with continued treatment (

3). Discontinuation rates for oral antipsychotics have been shown to be high: 74% at 18 months for chronic schizophrenia in the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) (

4) and 42% at 12 months for first-episode schizophrenia in the European First Episode Schizophrenia Trial (EUFEST) (

5). However, the risk of relapse needs to be weighed against the likelihood and severity of adverse effects caused by antipsychotic medication (

6) and the fact that approximately 20% of first-episode patients experience only a single episode of psychosis (

1).

Medication nonadherence rates are high in schizophrenia, as they are in many chronic medical conditions. Three systematic reviews on adherence to antipsychotic medication for psychosis noted that patients took an average of 58% of the recommended amount of medication (

7), that 41.2% of patients did not regularly take medication as prescribed (

8), that prescription completion rates ranged from 28% to 85% (

9), and that irregular medication use rates ranged from 31% to 62% (

9). Many of the studies were based on interviews or questionnaires, so patients not willing to participate were not included. Thus, nonadherence rates are probably higher in unselected patient populations. Current guidelines for schizophrenia include long-acting injections of antipsychotics as an option for maintenance treatment, particularly for overcoming established nonadherence (

1,

2,

10). Two earlier systematic reviews on depot injections (

11,

12) suggested a nonadherence rate of only 24% (range=0%–54%), and more recently Shi et al. (

13) calculated the mean medication possession ratio (cumulative number of days covered by depot divided by 365 days) to be 91% for patients receiving depot first-generation antipsychotics.

Studies comparing clinical outcomes for depot and oral antipsychotics vary in study design and methodological rigor as well as in their primary findings. A meta-analysis (

14) showed no difference in the risk of relapse for depot first-generation antipsychotics compared with oral medications, although global improvement was more likely in the depot cohort. However, patients for whom depot medication is most indicated—those who are nonadherent with oral formulations—are likely to be underrepresented in randomized controlled trials. Observational studies are generally more supportive of depot medication; mirror-image (before-after) studies show a consistent benefit for depot medication over prior medication in terms of reducing total number of days in hospital, but a major problem in these studies is that, by definition, the initial (oral) medication has failed (

15,

16), and the temporal order of medications (first oral, then depot injection) may have a substantial effect on the medications' comparative effectiveness.

Depot antipsychotics are not widely prescribed after a first episode of psychosis (

17), even though nonadherence rates in first-episode patients are high and are strongly linked to relapse (

18). Relapse at this crucial period in early adulthood can have marked psychosocial consequences in terms of education or work opportunities. The low use of depot antipsychotics at this point in the illness process may reflect a presumed dislike of injectable medication among first-episode patients and negative attitudes associated with use of depot injections (

19,

20). However, several studies have suggested that depot medications are effective and acceptable in patients with first-episode psychotic illness (

17,

21). Unfortunately, there is a dearth of long-term data comparing the use of depot and oral antipsychotics after first-episode psychosis (

22).

Using case linkage of the comprehensive national databases available in Finland, we analyzed data from a large nationwide cohort of patients discharged after a first hospitalization in which schizophrenia was diagnosed to assess risk of rehospitalization, all-cause discontinuation, and total mortality for patients using any antipsychotic or no antipsychotic and for patients receiving depot formulations or the equivalent oral formulations. We also compared commonly used depot antipsychotics with the most commonly used oral second-generation antipsychotics that are not available in depot formulation to further answer the question of which are the most effective antipsychotics in the maintenance phase after a first hospitalization for schizophrenia, as assessed by risk of rehospitalization. We hypothesized that there would be no differences between different antipsychotic drugs, irrespective of whether they were administered orally or as a depot injection.

Method

This was a register-based case linkage study of all people in Finland 16–65 years of age who had their first hospitalization in which schizophrenia was diagnosed (ICD-10 code F20) during the period of 2000–2007 and who had not collected (i.e., purchased) any antipsychotic prescription (Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical [ATC] code N05A) within 6 months before admission.

The study cohort was identified from the Finnish National Hospital Discharge Register, which is administrated by the National Institute for Health and Welfare. A total of 33,318 patients had at least one hospitalization due to schizophrenia-related illness (ICD-10 codes F20–F25) during the study period. Of these, 7,434 experienced their first hospitalization during that period, and 2,588 had a strictly defined schizophrenia diagnosis (F20) during their first hospitalization. Detailed information about the prescription database and the procedure for calculating the duration of antipsychotic use is presented in the data supplement that accompanies the online edition of this article.

Statistical Analysis

The outcome measures of interest were 1) the risk of all-cause discontinuation of the initial antipsychotic medication; 2) the risk of rehospitalization for schizophrenia; and 3) the risk of death. Only those patients who had received any antipsychotic medication within the first 30 days after discharge were included in the analysis of all-cause discontinuation. The follow-up for each patient started at the end of the first hospitalization period. The end of follow-up for the whole study was December 31, 2007. For the analysis of all-cause discontinuation (N=1,507), patients' follow-up ended at the time their initial treatment changed for any reason, at death, or at the end of the study period, whichever occurred first. For the analysis of rehospitalization (N=2,588), follow-up ended at the time of the first rehospitalization, at death, or at the end of the study period. For the mortality analysis, follow-up ended at death or at the end of the study period. Detailed information about the statistical analysis is presented in the online data supplement.

Results

The mean age of the study population was 37.8 years (SD=13.7), and 62% were male. Of 2,588 patients with a first hospitalization, 1,507 (58.2%) used an antipsychotic medication during the first 30 days after discharge, and 1,182 (45.7% of the total, 95% confidence interval [CI]=43.7–47.6) continued the initial antipsychotic medication (started within 30 days after hospital discharge) for 30 days or longer. Alternatively, 54.3% of our cohort either did not collect an antipsychotic prescription within 30 days of hospital discharge or used their initial antipsychotic medication for less than 30 days.

The association between clinical and sociodemographic variables and the risk of all-cause antipsychotic discontinuation over a mean follow-up period of 2 years (5,221 person-years) is summarized in Table S1 in the online data supplement. During the follow-up period, 1,394 patients discontinued their initial antipsychotic medication (started not only during the first 30 days but at any time during follow-up) for the following reasons: 50.6% (705 patients) because of a change in antipsychotic prescription, 34.3% (478 patients) because of discontinuation, 14.8% (207 patients) because of hospitalization, and 0.3% (four patients) because of death.

The all-cause drug discontinuation risks and the median dosages for each medication are listed in Figure S1 in the online data supplement.

Table 1 lists the pairwise comparisons for all-cause discontinuation between depot antipsychotics (mean age, 46.4 years; mean duration of first hospitalization, 95.9 days) and their equivalent oral formulations (mean age, 39.8 years; mean duration of first hospitalization, 63.5 days). Of a total depot monotherapy of 298 person-years, 73 person-years (24.5%) consisted of treatment that was started within 30 days after discharge from the first hospitalization. For haloperidol, perphenazine, and risperidone, the depot formulation was associated with a significantly lower risk of discontinuation than was the oral formulation. In the pooled analysis of depot and oral antipsychotics (haloperidol, perphenazine, risperidone, and zuclopenthixol), depot antipsychotics were associated with a 59% lower risk of discontinuation than oral antipsychotics (hazard ratio=0.41, 95% CI=0.27–0.61, p<0.0001).

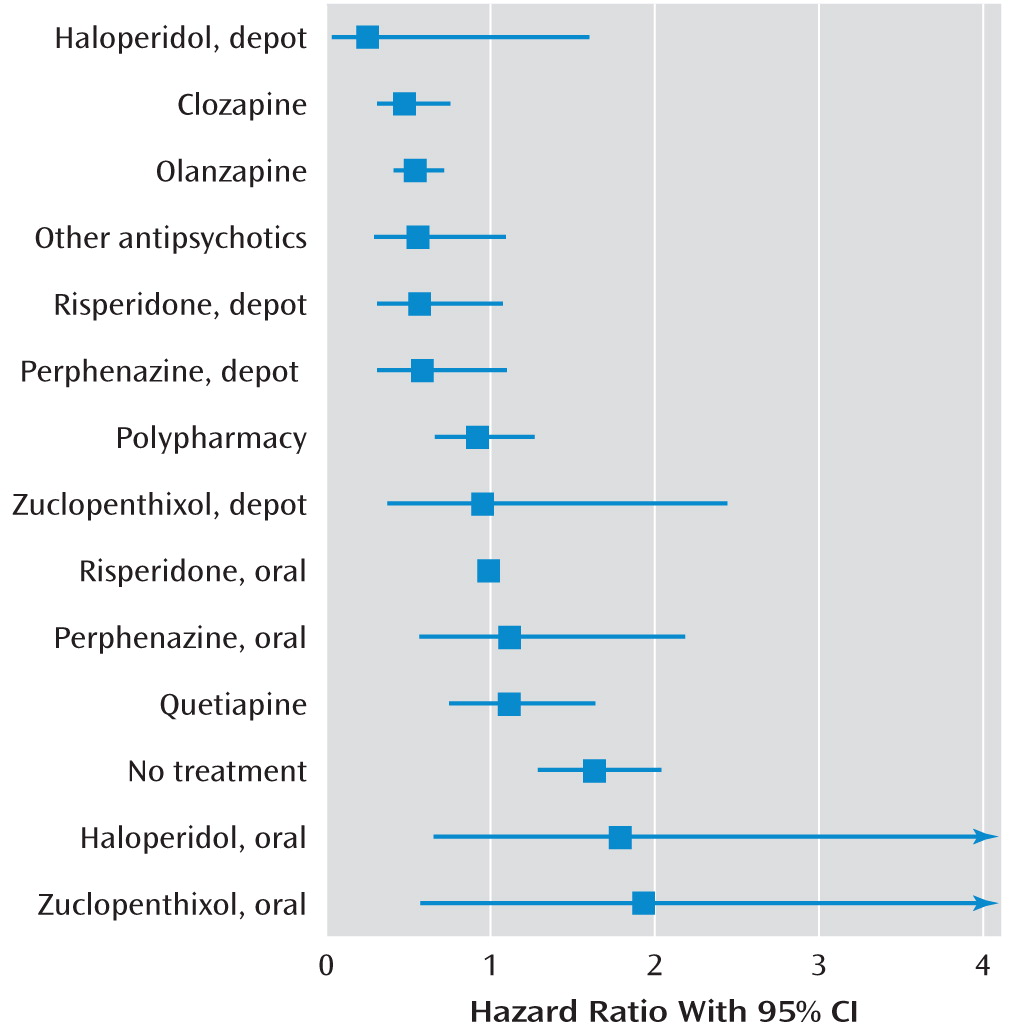

During a mean follow-up period of 2.0 years (5,221 person-years), 1,496 patients (57.8%) were rehospitalized because of a relapse of schizophrenia symptoms. Compared with no use of antipsychotics, use of any antipsychotic was associated with a lower risk of rehospitalization (Cox model hazard ratio=0.38, 95% CI=0.34–0.43; marginal structural model hazard ratio=0.48, 95% CI=0.42–0.56). The risk of rehospitalization for individual antipsychotics is summarized in

Table 2 and

Figure 1. Only clozapine (fully adjusted hazard ratio=0.48, 95% CI=0.31–0.76) and olanzapine (hazard ratio=0.54, 95% CI=0.40–0.73) were associated with a significantly lower risk of rehospitalization than oral risperidone. In the pairwise comparisons between depot agents and their equivalent oral formulations, no significant differences in rehospitalization risk were observed between pairs, but in the pooled analysis, depot agents were associated with a significantly lower risk of rehospitalization (adjusted hazard ratio=0.36, 95% CI=0.17–0.75, p=0.007; weighted mean=0.53, 95% CI=0.32–0.88) (

Table 1).

There were 160 deaths during the follow-up period. Use of any antipsychotic (64 deaths/6,260 person-years) compared with no use of antipsychotic (96 deaths/4,509 person-years), when considered in terms of number of deaths per person-years, was associated with a lower risk of mortality (Cox model hazard ratio=0.49, 95% CI=0.34–0.72; marginal structural modeling hazard ratio=0.38, 95% CI=0.19–0.74). When the hospital episodes were excluded from the time at risk for death (16 deaths censored), the hazard ratio was reduced to 0.45 (95% CI=0.31–0.67). Because of the low number of deaths, the confidence intervals were wide, and no statistically significant differences in mortality were observed between antipsychotic medications.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study of the adherence and comparative effectiveness of specific antipsychotic treatments in a large unselected population of patients in a real-world setting after their first hospitalization with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. The results showed that in Finland, a high-income country where the cost of antipsychotic medication is fully reimbursed, more than half of patients either did not collect an antipsychotic prescription within 30 days after discharge from their first hospitalization or discontinued their initial antipsychotic medication within 30 days. This finding was not attributable to selection bias, since the study population included all patients in Finland with a first hospitalization for schizophrenia. No information was available on the medication used in the hospital, but it can be assumed that virtually all patients had received some kind of antipsychotic treatment (

23). Because there is no compulsory outpatient treatment in Finland, our results on the comparative effectiveness of specific antipsychotics can be generalized only to those patients who are willing to use antipsychotic treatment in outpatient care.

In two previous large randomized controlled trials, the all-cause discontinuation rates were 74% for all patients at 18 months (in the CATIE study [

4]) and 42% at 12 months (in the EUFEST study [

5]); at 2 months, the all-cause discontinuation rates in those studies were substantially lower than 50%. This may be explained by selection and follow-up of the patients: in a real-world setting, patients may be less motivated or less cooperative, and routine clinical care and follow-up are less intensive than in randomized controlled trials. Also, the participants in CATIE were patients with a previously established pattern of antipsychotic treatment. On the other hand, one might have expected that continuation would be favored in clinical practice, since medication is not blinded, as it is in double-blind randomized controlled trials, but is generally chosen by the patient and clinician. Not all discontinuations in our study can be assumed to indicate nonadherence; some patients would have stopped medication between prescriptions because of other events, such as medication switch, rehospitalization, and death. However, approximately one-third of discontinuations did not precede such an event, and it is reasonable to assume that most of these cases do represent nonadherence; it is unlikely that clinicians would deliberately stop medication early when the diagnosis is schizophrenia.

The mean age of the patients was greater than 37 years. This relatively high age is probably due to delays in settling on a strictly defined diagnosis of schizophrenia, since 21% of the patients had a history of antipsychotic use in outpatient care (earlier than 6 months before the index hospitalization). A 1966 birth cohort study (N=11,017) in northern Finland (

24) showed that until age 27, all 37 cohort members who were listed in the national treatment register as being hospitalized with a schizophrenia diagnosis were in fact found to have schizophrenia when researchers applied DSM-III-R criteria to the information in available hospital records (0% false positive)—but the study authors found an additional 34 patients hospitalized with other diagnoses of psychotic illness who also fulfilled DSM criteria for schizophrenia (48% false negatives). Thus, it is likely that many patients had symptoms and transient antipsychotic treatment before their first hospitalization with a schizophrenia diagnosis (although those patients who used antipsychotics in outpatient care during the 6 months preceding our study period were excluded).

The use of defined daily dosage in our study may have caused some patients continuously using unusually low doses to have been misclassified as discontinuing the medication. On the other hand, our nonadherence results may be underestimates, as it was assumed that all patients who collect a prescription on time are fully adherent. It is probable, too, that many discontinuations that we classified as being due to rehospitalization were attributable to nonadherence (that is, the prescription was filled, but the medication was not taken as prescribed). Our results indicate that nonadherence with antipsychotic medication is a major issue in first-episode schizophrenia and occurs very early on, perhaps contributing to a relatively poor long-term prognosis in schizophrenia.

Depot injections were associated with about a 50%–65% lower risk of rehospitalization than oral formulations of the same compounds even when the temporal sequence of medications used was taken into account. In a systematic metareview of randomized controlled trials (

14), no difference was observed in relapse rates between depot and oral antipsychotics. This is understandable, as patients who are adherent and cooperative enough to participate in a randomized controlled trial would not likely receive much additional benefit from a formulation designed to enhance adherence. Since nonadherent patients cannot be forced to participate in randomized controlled trials, observational studies are the only way to investigate this issue. A recent systematic review comparing depot and oral formulations (

16), which included observational data, found variable results but noted several studies in which depot use was associated with less time in hospital and better global outcomes. In our nationwide cohort, about 8% of patients used depot injections as their first medication in outpatient care, and about 10% of the treatment patient-years consisted of depot medication (see

Table 2; also see Figure S1 in the online data supplement). This is a low rate of use compared with that seen in chronic schizophrenia. A recent review (

25) concluded that depot agents were prescribed for one-quarter to one-third of patients in the U.K., depending on clinical setting. It can be assumed that depot agents are used especially among those patients with the lowest treatment adherence (

8,

26). Also, in the Finnish Guidelines for Treatment of Schizophrenia (

23), oral first- or second-generation antipsychotics are recommended for treatment of acute and chronic patients, and depot formulations are recommended for those patients with inadequate insight and treatment compliance. If the target population for depot medication were broadened, then patients with better insight and treatment adherence would be included, and a reduction in rehospitalization rate would be expected. However, this reduction can be achieved only among those patients who are willing to use antipsychotic treatment in outpatient care. The Finnish Guidelines for Treatment of Schizophrenia indicate that patients must be seen by the medical staff at least once a month in outpatient care during the first 6 months after discharge from hospital (

23). However, no comprehensive data are available on how strictly these guidelines are followed throughout the country.

A recent meta-analysis (

27) of 15 randomized controlled trials with a total of 2,522 patients with early psychosis did not observe significant differences in efficacy between atypical and conventional antipsychotics, but the study did not look at differences within these two groups of antipsychotics. In our study, of the oral medications studied, clozapine and olanzapine were associated with the lowest all-cause discontinuation and rehospitalization rates. These findings are in line with those from the CATIE (

4,

28) and EUFEST (

5) studies as well as our previous cohort study (

29). It should be noted that about 6% of patients died during a mean follow-up of 4 years in this cohort of patients 16–65 years of age. Use of any antipsychotic was associated with significantly lower mortality compared with no antipsychotic treatment, which is also in keeping with previous cohort studies (

29,

30), although the relatively low statistical power meant that no significant differences were observed between individual antipsychotic treatments.

In observational studies, adjusting for confounding factors is important. Although we used a number of clinical and sociodemographic factors in the analyses, we had no direct measure for intrinsic treatment adherence or risk of relapse. Therefore, in the comparison of rehospitalization risk, we made a further adjustment by using the choice of the initial antipsychotic, reflecting the patient's clinical status at baseline and thus the clinical correlates determining the selection of the initial treatment, as a covariate. Such an adjustment resulted in major change in only one medication category: the rehospitalization risk for polypharmacy changed from a higher risk (1.25) to a lower risk (0.92) compared with oral risperidone. This suggests that patients receiving polypharmacy (several antipsychotics) as their first treatment in outpatient care are among the most severely ill patients (having a high intrinsic risk of relapse), and when this factor is adjusted, the hazard ratio for subsequent polypharmacy decreases. However, this did not change the statistical significance of the finding. When multiple comparisons are made, one must be cautious to draw conclusions based on the significance of the findings. When a Bonferroni correction was applied, clozapine and olanzapine differed significantly from oral risperidone in risk of rehospitalization.

Those patients who are more likely to be nonadherent with oral medication, and thus more likely to receive prescriptions for depot medication, are also likely to have poorer insight than other patients (

8,

26). In the United States, patients treated with depot medications have also been observed to use more alcohol and illicit drugs, to be more likely to have been arrested, to have more severe psychopathology (such as psychotic symptoms and disorganized thinking), and to have more previous psychiatric hospitalizations than patients using oral antipsychotics (

13). Therefore, it is unlikely that residual confounding would explain the better outcome among patients receiving depot antipsychotics. No substantial differences were observed between the results obtained by Cox models and marginal structural modeling analyses using causal models, which suggests that the results are not subject to major bias. In all previous studies of depot compared with oral formulations, it has not been possible to take into account the medication history and temporal sequence of the medication (first oral, then depot medication, compared with first depot, then oral medication). Our results indicate that depot medications are associated with substantially better outcomes even when this issue is accounted for. Although there is no compulsory outpatient care in Finland, the regular contact with the health care personnel providing depot injections may have a beneficial effect on patients' outcome. The low number of patients receiving depot haloperidol resulted in wide confidence intervals, and therefore no firm conclusions can be drawn about its effectiveness.

We were not able to assess patients' subjective quality of life during the treatments. Specific antipsychotics differ markedly in their side effect profiles (

6), and all available antipsychotic medications are far from ideal with regard to efficacy and tolerability. In this study, about 50% of all-cause discontinuation was attributable to switch to another antipsychotic (or from monotherapy to polypharmacy or from polypharmacy to monotherapy). This implies that a majority of patients are not averse to pharmacological treatment per se but that the treatments studied are not sufficiently efficacious or well tolerated, resulting in frequent switching of medication.