Parkinson's disease, the second most common neurodegenerative disorder in the United States, is defined by the motor triad of tremor, rigidity, and bradykinesia. The majority of patients also experience nonmotor complications (

1), which are more closely associated with rates of disability and distress than the motor symptoms of the disease (

2). Depression, the most prevalent nonmotor concern (

3), affects approximately 50% of Parkinson's disease patients (

4). Depression in Parkinson's disease is characterized by high rates of psychiatric comorbidity (

5) and executive dysfunction (

6) and is linked to faster physical and cognitive decline (

7), poorer quality of life (

8), and increased caregiver burden (

9). Despite these negative effects, there is currently no evidence-based standard of care.

Pharmacological interventions have received the most empirical attention to date. Antidepressants (

10,

11), dopamine agonists (

12), and alternative treatments, such as omega-3 fatty acids (

13), have demonstrated beneficial effects in preliminary controlled studies. Psychotherapeutic approaches, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), have been the focus of fewer scientific investigations, despite demonstrated efficacy among the aged (

14) and in other debilitating medical conditions (

15). Only small pilot studies have examined the utility of CBT for depression in Parkinson's disease, with promising results (

16–

21). In other patient groups, CBT has shown effects comparable to those of antidepressants for mild depression, with combination treatment appearing most effective for moderate-to-severe forms of depression (

22). Additional research is needed to inform the development of specific treatment recommendations for this medical population.

The purpose of the present study was to conduct the first randomized, controlled trial of CBT for depression in Parkinson's disease. We hypothesized that CBT would result in greater decreases in depressive symptoms, anxiety, negative thoughts, sleep disturbance, and caregiver burden, as well as greater improvements in quality of life, coping, and social support, than clinical monitoring (with no new treatment). Furthermore, we hypothesized that there would be more treatment responders in the CBT group. The effect of CBT on Parkinson's disease symptom ratings was also examined.

Method

This study received full approval by the Robert Wood Johnson Medical School Institutional Review Board. After complete description of the study to participants, written informed consent was obtained (prior to the initiation of any study procedures). Participants received the study treatment at no cost and were compensated $20.00 for each in-person assessment and $10.00 for each telephone assessment. Treatment and evaluation occurred at the Robert Wood Johnson Medical School. Participants enrolled in the study with a caregiver.

One-half of the participants received CBT plus clinical monitoring. The other half received clinical monitoring only. This additive design has been recommended for use when exploring the relative efficacy of a new psychotherapy intervention (

23).

All participants continued to maintain stable medical regimens under the care of their personal physicians. Depression was addressed in the same manner in which it was handled prior to the study (e.g., antidepressant medication at a stable dose). No new depression treatment (other than CBT in the experimental condition) was provided to study participants. Those assigned to the comparison group (clinical monitoring only) had the option to receive the CBT treatment package after week 14.

Participants

Patients were recruited from the Richard E. Heikkila Movement Disorders Clinic, local newspapers, and the New Jersey Chapter of the American Parkinson's Disease Association between April 2007 and March 2010. The final follow-up evaluation occurred in July 2010. Patients were eligible for participation in the study if they 1) had a diagnosis of Parkinson's disease per research criteria (

24); 2) had a diagnosis of primary major depression, dysthymia, or depression not otherwise specified per DSM-IV criteria; 3) had a Clinical Global Impression–Severity scale score ≥4 (at least moderately ill [

25]); 4) were between 35 and 85 years old; 5) were receiving a stable medication regimen for a duration of ≥6 weeks; and 6) had a family member or friend willing to participate.

Expert panel guidelines were followed regarding the diagnosis of depression in Parkinson's disease (

26). Patients with comorbid anxiety disorders were eligible to enroll as long as their depressive disorder was primary.

Participants in both study groups (CBT plus clinical monitoring and clinical monitoring only) continued with mental healthcare (other than CBT) that was stabilized (≥6 weeks) prior to baseline. Medication use and mental healthcare utilization were tracked throughout the study. New depression treatment was a criterion for early termination.

Exclusion criteria were 1) dementia (a score below the 5th percentile for age on memory and on at least one other subscale of the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale [

27]); 2) off-time (time when medication is not effective and symptoms return) ≥50% of the day; 3) suicidal ideation; 4) unstable medical conditions; 5) bipolar, schizophrenia spectrum, or substance abuse disorders (as determined by DSM-IV criteria); and 6) receiving CBT elsewhere.

Caregiver inclusion criteria were 1) ages 25–85 years, 2) daily contact with the study participant, and 3) no unstable medical or psychiatric conditions (as determined via clinical interview).

Randomization and Masking

Appropriate candidates were allocated to receive CBT plus clinical monitoring or clinical monitoring only (1:1 ratio) by computer-generated random assignment (run by the statistical consultant [M.A.G.]). Randomization was stratified by antidepressant use at screening (yes/no) and conducted in blocks of six consecutive participants within each stratum.

All follow-up (i.e., postbaseline) assessments were conducted by independent evaluators without knowledge of the treatment condition. Participants were instructed not to reveal their group assignment to raters. Participants and therapists were not blind given the nature of the treatment.

Procedure

Potential participants called our office to receive information about the study and to complete preliminary screening (see Figure 1 in the data supplement accompanying the online version of this article). Appropriate individuals were scheduled for a face-to-face appointment, where a statement of informed consent (for both patient and caregiver) was reviewed and signed, demographic information was obtained, inclusion/exclusion criteria were assessed (by R.D.D., M.H.M., and M.M.), and baseline evaluations were completed. Those who met eligibility criteria were enrolled and randomly assigned to one of the two aforementioned treatment arms. Participants were reassessed at 5 (midpoint), 10 (end of treatment), and 14 weeks postrandomization (1-month follow-up evaluation). Telephone calls to participants were made at weeks 2 and 7 to assess patient safety.

Raters received extensive training from the first author (R.D.D.) in administration of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D [

28]), and the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A [

29]). Interviews for both Hamilton rating scale measures were standardized (by R.D.D.) at the outset of the trial, and a coding dictionary was developed to facilitate accurate scoring of participant responses.

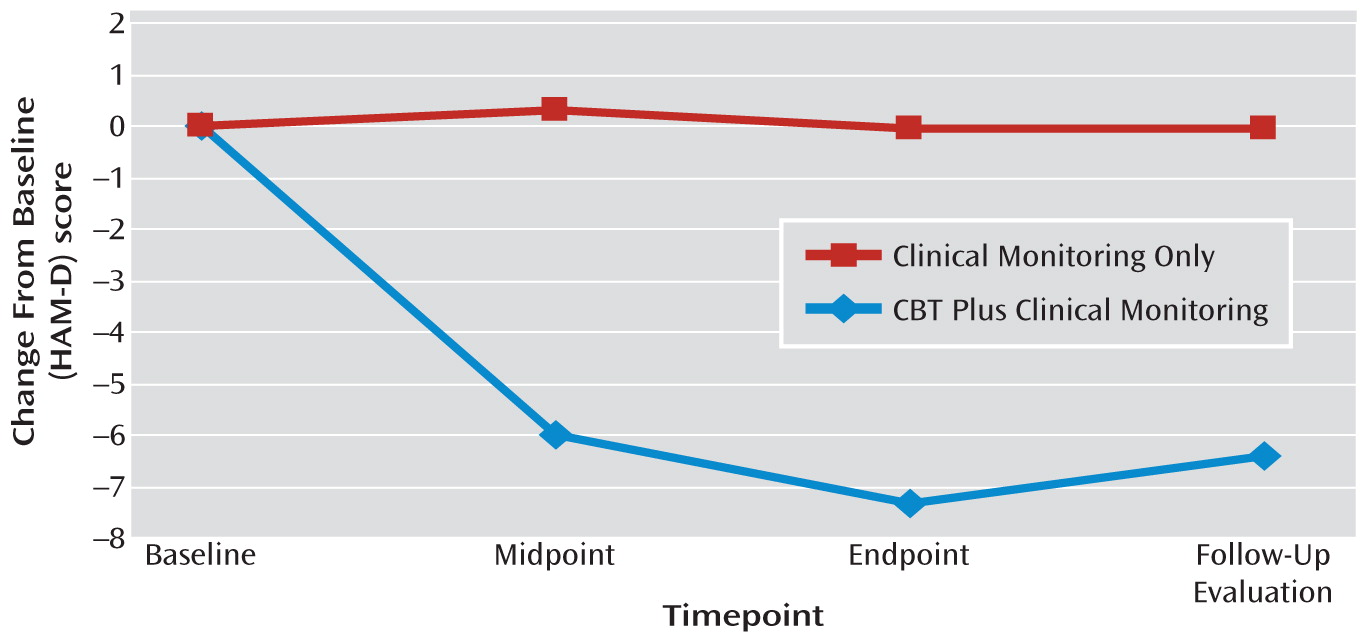

Change in the HAM-D total score was the primary outcome. HAM-D interrater reliability was >0.95 (intraclass correlation coefficient, based on 234 interviews [with 50 participants] selected by computer-generated random numbers). Secondary outcomes were 1) responder status (defined a priori as depression much improved or very much improved based on Clinical Global Impression–Improvement scale ratings or a reduction of at least 50% from baseline in the HAM-D total score [

30]); 2) depression (measured by the Beck Depression Inventory [BDI] [

31]); 3) anxiety (based on the HAM-A score); 4) negative thoughts (measured by the Inference Questionnaire [

32]); 5) sleep (measured by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index [

33]); 6) quality of life (measured by the social functioning, physical role limitations, and physical disability subscales of the Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form Health Survey [

34]); 7) coping (measured by the positive reframing and problem-focused subscales of the brief COPE scale [

35]); 8) social support (measured by the Social Feedback Questionnaire [

36]); 9) caregiver burden (measured by the Caregiver Distress Scale [

37]); and 10) Parkinson's disease symptoms (based on the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale total score [

38]).

All scales were completed at baseline, week 5, endpoint (week 10), and the week 14 follow-up evaluation except the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale, which was given only at baseline and endpoint.

Intervention

CBT.

The CBT employed in this trial was tailored to the unique needs of the Parkinson's disease population and is described in detail elsewhere (

19,

39). In brief, specific modifications included 1) a stronger emphasis on behavioral and anxiety management techniques than what is traditionally integrated into CBT protocols for depression and 2) inclusion of a supplemental caregiver educational program. These changes were intended to address the psychiatric complexity and executive dysfunction that characterize this patient population.

Participants received 10 weekly individual sessions (60–75 minutes) of manualized CBT. Treatment incorporated exercise, behavioral activation, thought monitoring and restructuring, relaxation training, worry control, and sleep hygiene and was augmented with four separate individual caregiver educational sessions (30–45 minutes) that were intended to provide caregivers with the skills needed to facilitate participants' home-based practice of CBT techniques. For example, caregivers were taught to help participants identify negative thoughts and replace them with more balanced alternatives and were given tools to assist them in completing therapy goals (i.e., exercise, socializing). The primary focus was not to address the caregivers' own personal concerns. (The treatment manual is available upon request from the first author.)

Therapist Training and Treatment Fidelity

The first author (R.D.D.) and two doctoral-level psychologists (K.L.B. and J.F.) conducted CBT. Prior to treating the study participants, the latter two authors received extensive training in CBT for depression in Parkinson's disease, which included treating two nonstudy patients each, with audiotape review of all their sessions by the first author (N=40). Throughout the trial, the first author and an independent expert in CBT in medical populations (L.A.A.) reviewed audiotapes from the therapy sessions (N=150), based on training and supervision needs, and assessed therapist skill and treatment fidelity, on the Cognitive Therapy Scale (

40), a widely used and validated CBT competence measure (with a score ≥40 reflecting proficiency; mean score=55.74 [SD=6.52]).

Clinical Monitoring

All participants received close clinical monitoring of their depressive symptoms by study personnel via follow-up telephone calls (at weeks 2 and 7 [30 minutes at each timepoint]) and evaluations (at weeks 5, 10, and 14 [60–90 minutes at each timepoint]). All participants remained on stable treatment regimens under the care of their personal physicians, who also monitored their medical and psychiatric status. No new depression treatment (other than CBT in the experimental condition) was provided.

Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed using SAS, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.). An intent-to-treat approach was employed in all analyses, which included all 80 randomly assigned participants. The primary outcome (change in HAM-D total score) was evaluated at baseline and weeks 5, 10, and 14 using mixed-models repeated-measures analysis of variance (SAS PROC MIXED) with restricted maximum likelihood estimation. Treatment group (CBT plus clinical monitoring and clinical monitoring only), assessment point (baseline and weeks 5, 10, and 14), and their interaction were fixed effects. The randomly assigned participant was treated as a random effect. The group-by-time interaction was the fixed effect of interest. Spatial power (a function of the square root of days that a given assessment occurred for a given participant) was used to model the covariance structure for all analyses, since this model yielded the best fit for the data among all covariance structures examined. Gender, block, strata (antidepressant use), and baseline cognition (based on the Dementia Rating Scale total score) were examined as covariates. Because there was no significant effect for any of these variables, they were removed from the final model.

Responder status was examined separately at weeks 10 and 14 and cross-tabulated with treatment group. The Fisher's exact test was used to compare the rate of response between CBT plus clinical monitoring and clinical monitoring only. The aforementioned mixed-models analyses were used to explore all other secondary outcomes. Because multiple tests capitalize on chance, all p values for these secondary outcomes were adjusted for multiple tests by the Holm method using permutation-type resampling (100,000 resamples; two-tailed) in SAS PROC MULTTEST. Effect sizes were calculated for all primary and secondary outcomes. Planned contrasts to examine changes specific to a particular timepoint (i.e., week 10) were only conducted if the overall omnibus statistical test remained significant after adjustment for multiple comparisons. Least squared means are presented.

Sample size was determined a priori based on power analyses. Power calculations were based on the HAM-D total score, an alpha set at 0.05, power set at 0.80, a predicted effect size of Cohen's d (0.70), based on a previous CBT pilot investigation in Parkinson's disease conducted by the first author (

19) as well as published literature on CBT for depression (

41), and the potential for 20% attrition. These parameters indicated that 40 participants per group were needed to obtain the desired effect.

Discussion

The results of this first randomized, controlled trial suggest that CBT may be a feasible and possibly efficacious approach for treating depression in Parkinson's disease. Ninety percent of the sample completed the study, and 88% of participants randomly assigned to CBT plus clinical monitoring attended all 10 treatment sessions. CBT was associated with significant improvements on all clinician-rated and self-reported measures of depression. Gains were observed by the end of treatment (week 10) and maintained during the follow-up evaluation (week 14). Effect sizes were large for both the HAM-D (1.59) and BDI (1.1). Response rates favored CBT plus clinical monitoring relative to clinical monitoring only at weeks 10 (56% versus 8%, respectively) and 14 (51% versus 0%, respectively).

The CBT plus clinical monitoring group also reported greater improvements in quality of life, coping, and anxiety as well as less motor decline. These results underscore several points. First, CBT participants reported less avoidance of and greater enjoyment from social activities as well as the use of positive reframing as a coping strategy in response to daily stress. Second, treatment effects may generalize to the negative thoughts and avoidance behaviors that maintain anxiety. Third, the incorporation of anxiety management strategies, such as worry control and relaxation, into a CBT program for primary depression in Parkinson's disease may be useful. Lastly, consistent with previous findings, suboptimally treated depression may accelerate Parkinson's disease-related physical disability (

7,

42).

Although there was no significant group-by-time interaction on inferences, treatment responders exhibited larger decreases in negative thinking compared with nonresponders. Since negative thoughts are a primary target of CBT, it follows that people who did not respond to treatment would not exhibit changes in thinking patterns. Despite moderate effect sizes, the effect of CBT on problem-focused coping and perceptions of role limitations and physical disability was no longer significant after controlling for multiple comparisons. CBT also had no substantial effects on sleep, social support, or caregiver burden.

There are no controlled trials, to our knowledge, of CBT for depression in Parkinson's disease with which to compare these results. However, completion and response rates, as well as effect sizes, are comparable to those observed in randomized trials of CBT in other populations (

41). For example, the literature suggests that the average effect size of CBT for depression relative to a comparison condition similar to the one utilized in this study (i.e., no new treatment) is 0.67 (

41). Thus, this initial randomized, controlled trial offers preliminary data to suggest that the beneficial effects of CBT observed in other patient groups might not be attenuated by the disease process (i.e., neurodegeneration, neurotransmitter changes, dysfunction in brain regions/pathways).

This study has several limitations related to the interpretation of efficacy. First, the study design did not include an attention-matched control or alternative psychosocial intervention. Although the additive approach and comparison condition employed did control for threats to internal validity (i.e., time, spontaneous remission, regression to the mean, treatment history, effects of repeated testing) and are appropriate for use in early-phase psychotherapy trials (

23,

43), the role of nonspecific factors, such as the increased attention and social contact received by the CBT group, cannot be adequately explored. It is also not possible to isolate which aspects of the CBT package (e.g., caregiver sessions, exercise) were most helpful. Related to this, we cannot rule out the placebo effect as a partial explanation for differences between groups. However, several factors make this explanation less likely. Throughout the trial, it was emphasized that the effects of both study treatments (CBT plus clinical monitoring and clinical monitoring only) on depression in Parkinson's disease were not yet known and that there may not be any personal benefit from participation. Additionally, the chronic nature of depression in the sample, progressive nature of Parkinson's disease (i.e., not an acute stressor), durability of CBT gains exhibited over 14 weeks, changes in negative cognition that accompanied treatment response, minimal improvement observed in the clinical monitoring only condition, and comparability of results with CBT trials in other populations suggest that the effect of CBT may be larger than that which can be explained by placebo response alone. Of note, a CBT effect size of 0.75 is obtained when comparing CBT data from this study with pill-placebo data from our recent double-blind placebo-controlled antidepressant trial for depression in Parkinson's disease (

10).

Second, despite an average reduction of 7.35 points, the mean HAM-D score of 13.58 for the CBT group at week 10 still reflects moderate depressive symptoms. This finding may be in part a result of the high rate of somatic complaints experienced by Parkinson's disease patients, independent of depression, as well as the inclusive scoring approach employed (

44). For example, all reported symptoms were counted toward HAM-D ratings, despite potential overlap with the physical symptoms of Parkinson's disease (i.e., psychomotor slowing, fatigue). Importantly, the BDI emphasizes cognitive symptoms of depression (i.e., guilt, hopelessness), and the mean week-10 BDI score of 9.7 for the CBT group indicates minimal symptoms of depression. Third, given the psychiatric comorbidity in the sample and the inclusion of two anxiety management modules in the CBT package, it is possible that reduced anxiety could have influenced depression treatment response. Because the depression effect remained robust (p<0.0001) when controlling for change in the HAM-A score (exploratory analyses), it is unlikely that improved anxiety was a main mechanism of action. Fourth, motor functioning results warrant prudent interpretation. Although the group-by-time interaction on motor scores at week 10 was statistically significant, the effect size was small (0.13) and may be an artifact of the sample.

It is also necessary to acknowledge that our results may not generalize to those in more advanced stages of disease or with severe depression, dementia, suboptimal social supports, inability to travel to weekly therapy, and limited access to specialized mental health resources. In addition, we could not explore the longer-term durability of treatment gains because the follow-up period was limited to 1 month for ethical reasons (protocol restrictions regarding changing depression treatment). Lastly, treatment side effects were not assessed prospectively. Collectively, these limitations suggest that the results should be viewed as a preliminary first step in the establishment of an evidence base for CBT in the treatment of the psychiatric complications of Parkinson's disease.

The precise cause of depression in Parkinson's disease is unclear, with both biological and psychosocial factors implicated in its onset and maintenance (

45). As a whole, the results of this trial suggest that CBT for depression in patients with Parkinson's disease may be beneficial, independent of etiology. Further research is needed to replicate and extend these findings.