The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not approved any drug for treating the neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. However, atypical antipsychotics are commonly used for off-label treatment (

1). In April 2005, the FDA issued a black box warning that the use of atypical antipsychotics to treat behavioral disturbances in patients with dementia was associated with greater mortality. Subsequent research reports confirmed the mortality risks associated with the use of both conventional and atypical antipsychotics to treat patients with dementia (

2–

5). Another FDA black box warning for conventional antipsychotics followed in June 2008 (

6).

Information about mortality associated with individual antipsychotic agents in patients with dementia is limited. One study (

7) found no significant mortality differences between olanzapine and risperidone. However, the number of deaths during this trial was small with wide confidence intervals. In a 2005 meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials (

2), no greater risk of death was observed with any individual atypical antipsychotic; however, there may have been inadequate power to detect significant differences after controlling for confounding variables between trials. A study comparing the most frequently prescribed antipsychotic drugs in Canada (

8) found higher 180-day mortality ratios for haloperidol and loxapine, but no difference between olanzapine and risperidone. The most recent study (

9), using case-control methodology, found that patients with dementia taking haloperidol, olanzapine, and risperidone, but not quetiapine, had short-term increases in mortality compared with patients who were not taking these agents.

Large-scale comparisons of mortality with individual antipsychotic agents that control for important confounders are currently lacking. Using multivariate and propensity-scoring methods, we examined mortality risks in outpatients with dementia in the 6 months after the start of treatment with a new antipsychotic, and we focused on the most commonly used individual agents for patients with dementia in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system (risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, and haloperidol). Based on evidence from our earlier research that anticonvulsants had similar mortality risks to antipsychotics (

3) and that there was a small but significant increase in their use after the FDA black box warnings (

10), valproic acid and its derivatives were also included for comparison.

Method

Study Cohort

This study was approved by the VA Ann Arbor Health Care System institutional review board. Data were provided by national VA registries maintained by the Serious Mental Illness Treatment, Resource, and Evaluation Center in Ann Arbor, Mich. The patients were ≥65 years old; had a dementia diagnosis between October 1, 1998, and September 30, 2008 (ICD-9 codes: 290.0, 290.1x, 290.2x, 290.3, 290.4x, 291.2, 294.10, 294.11, 331.0, 331.1, and 331.82); and began outpatient treatment with a study medication after a 12-month “clean period” without exposure to antipsychotics or anticonvulsants. Over 87% of patients in the sample were treated with monotherapy during the 6-month follow-up. Given that switching to other antipsychotic agents might obscure risk profiles for individual antipsychotics, we restricted the final sample to these monotherapy patients. The final study sample included 33,604 patients.

Medications

We included risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, and haloperidol, as well as valproic acid and its derivatives (an anticonvulsant group commonly used as a second-line treatment strategy for the neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia) in our study. Patients taking valproic acid and its derivatives (sodium valproate or divalproex) who also had seizure disorders (N=337) were excluded from the sample because their anticonvulsant use was less likely to be related to dementia.

Clinical Characteristics

Mortality data were obtained from the U.S. National Death Index (National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, Md.). Other variables included age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, and indicators of psychiatric and medical comorbidity (the latter using a modified version of the Charlson comorbidities index [

11] based on 18 medical comorbidities [excluding dementia] in the year preceding new medication start). As delirium frequently occurs in patients with dementia and is an independent mortality risk factor (

12), and antipsychotics are often prescribed for delirium, we also assessed for the presence of a delirium diagnosis at the time of prescription. We used a coding scheme for acute confusional states developed for a previous study (

13) that included the following ICD-9 codes: 290.3, 291.0, 292.0, 292.1, 292.2, 292.9, 293.0, 293.1, 293.9, 294.8, 294.9, 348.3, 437.2, 572.2, 290.11, 290.41, 292.81, 293.31, 293.82, 293.83, 293.89, and 349.82. To control for potential changes in treatment practices, particularly given the impact of the black box warning (

10), calendar time at the new medication start was included as a covariate. The model also included number of hospitalizations and nursing home days in the year before the new medication was started and size, rurality, and academic affiliation of the VA medical center at which the medication was prescribed.

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to categorize patient characteristics by type of medication prescribed. A 180-day follow-up period was chosen based on the duration of trials in the FDA's analysis and because it had been used in previous studies (

8,

14). We examined medication exposure days in both intent-to-treat and exposure analyses. For the intent-to-treat analyses, exposure time was 6 months or time until death, whichever came first. For the exposure analyses, exposure to a specific antipsychotic or valproic acid and its derivatives began on the date of the first filled prescription; exposure was censored at the end of the exposure period, at 6 months, or at time of death, whichever came first. As in a previous study (

2), the exposure period continued for the duration of medication supply plus 30 days. Any gaps in prescription fills of less than 30 days were considered continued exposures. This accounts for some level of continued exposure and biological effect among patients who missed doses or used lower than prescribed doses.

For each of the medication types, mortality during the 180-day follow-up was calculated per 100 person-years, and distribution of time to death since index prescription was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis method (

15).

A variety of approaches were used to deal with potential selection biases. Initially, we used multivariate analyses that included potential confounders available in administrative data. Additionally, we used propensity-weighted and propensity-stratified methods. Both methods attempt to control for treatment by indication in observational studies by adjusting for the predicted probability that a patient will receive a specific treatment conditional on the patient's baseline covariate values. The propensity-weighted analyses estimated hazard ratios using the Cox regression model, with observations weighted inversely by the propensity estimates obtained using multinomial models, permitting comparisons across multiple medications based on the one model (

16). For the propensity-stratified analyses, we made comparisons between pairs of medications, with each medication compared against risperidone. For each pairwise comparison, we estimated propensity scores using logistic regression, and we obtained hazard ratio estimates using the Cox regression model stratified by the estimated propensity quintiles. In both propensity-weighted and propensity-stratified methods, models used to obtain propensity scores were optimally fit to be highly predictable without consideration for parsimony.

Our secondary analyses included examination of the site of care (psychiatric compared with nonpsychiatric setting) and adjustment for antipsychotic dosage, which was standardized to haloperidol equivalents (

17). After a visual inspection of the smoothed hazards revealed decreasing hazards over time for haloperidol, we also extended the Cox regression model to test for nonproportional hazards using logarithmically transformed time-by-medication indicator interaction terms. Upon finding significantly decreasing risks over time for haloperidol, we divided the time since medication start into 30-day intervals, and we used a piecewise exponential model to compare relative risks between medications at different time intervals.

To confirm that our conclusion was not biased by including only those patients treated with monotherapy, we also performed a true intent-to-treat analysis in which patients who switched or augmented their initial medication were included. This analysis characterized this patient population by their exposure to the initial medication.

Last, we conducted two additional analyses to further examine mortality risk differences: 1) an exploration of whether the larger proportion of Parkinson's disease patients in the quetiapine cohort may have resulted in a lower mortality risk; and 2) an analysis that further examined haloperidol's role as the agent with the highest mortality by comparing a number of key variables in haloperidol and risperidone users and individually matching these variables for each haloperidol patient with up to two risperidone patients.

Results

Characteristics of the Study Population

Table 1 summarizes demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients in each medication group. Haloperidol users were significantly older and sicker (as evidenced by the highest Charlson comorbidity index scores, highest rates of concurrent delirium, and more inpatient days in the preceding year) than users of the other study medications. A higher percentage of African American patients were treated with haloperidol compared with the other agents. Those taking haloperidol were also significantly more likely to have used opioids or benzodiazepines and less likely to have used antidepressants during the year preceding the new antipsychotic start. Users of the various atypical agents had similar rates of medical and psychiatric comorbidities with the exception of significantly higher rates of Parkinson's disease in quetiapine users. Users of valproic acid and its derivatives tended to be younger, were less likely to be African American, and were more likely to have comorbid bipolar disorder and other psychiatric illnesses than users of other agents.

Individual Medication Use and Mortality

The crude 6-month mortality rates were as follows: haloperidol, 20.0%; olanzapine, 12.6%; risperidone, 12.5%; valproic acid and its derivatives, 9.8%; and quetiapine, 8.8% (χ

2=294.4, df=4, p<0.0001). The mortality rate rankings were also consistent in the intent-to-treat and exposure analyses (

Table 2).

Multivariate adjustment and the propensity-weighted and propensity-stratified adjustments yielded similar results. Adjusted relative risks (

Table 3) averaged over a 180-day period consistently revealed that haloperidol had the highest mortality risk and quetiapine had the lowest risk. Valproic acid and its derivatives showed a higher risk than quetiapine but, in all but one analysis, a risk lower than the other antipsychotics.

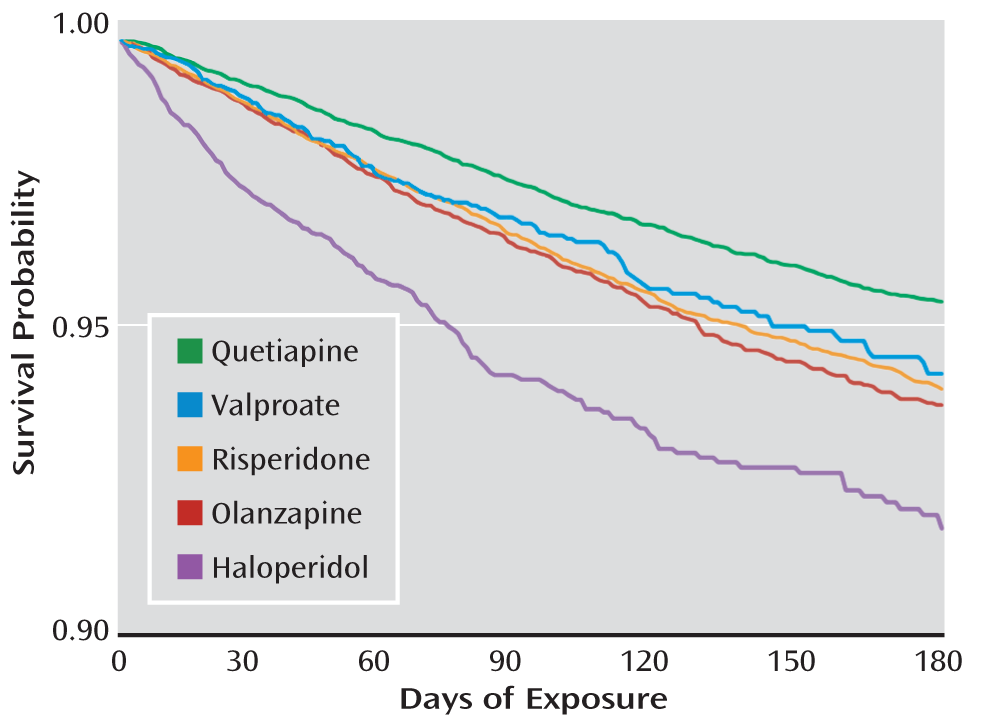

Figure 1 shows the covariate-adjusted survival function by days of exposure.

Secondary Analyses

Site of care.

Haloperidol users had the highest proportion of nonpsychiatric visits associated with the prescription (77.6%) compared with users of the other medications (52.4%–57.8%). An analysis stratified by prescription location produced results that were consistent with those from the main analyses, with haloperidol having the highest risk in both settings (propensity-stratified results: nonpsychiatric prescription relative risk=1.42, 95% CI=1.19–1.70, p<0.001; psychiatric prescription relative risk=1.41, 95% CI=0.93–2.13, p=0.1068) and quetiapine the lowest risk (nonpsychiatric prescription relative risk=0.75, 95% CI=0.64–0.88, p<0.001; psychiatric prescription relative risk=0.71, 95% CI=0.55–0.91, p=0.006).

Antipsychotic dosage.

Patients taking only “as-needed” antipsychotics (N=3,613) or valproic acid and its derivatives were not included in the analyses adjusting for dosage.

Table 4 shows summary statistics of initially prescribed and haloperidol equivalent doses. The majority of patients (81.6%) received initial haloperidol equivalent daily doses <1.5 mg, while 5.4% received prescribed doses ≥3 mg, and 13.0% received prescribed doses between 1.5 and <3 mg. Relative risk estimates adjusted for dosage showed mortality risk order consistent with the main analyses.

Changes in mortality risk over time.

Using a piecewise exponential model, mortality risk was found to be 1.5 times higher on average in the first 120 days than for the subsequent 60 days across all medications except haloperidol. Haloperidol risk was highest in the first 30 days (relative risk=2.24 compared with risperidone between 150 and 180 days, p<0.001), and then the risk significantly decreased to no difference between 90 and 120 days (relative risk=1.11 compared with risperidone between 150 and 180 days, p=0.65). Exposure days were significantly shorter for haloperidol than for other medications (median=60 days for haloperidol, compared with 111 days or longer for other medication groups). The relative risks between olanzapine and risperidone and between valproic acid and its derivatives and risperidone were not significantly different during the 180-day period. The quetiapine risk was consistently lower than that of risperidone, with relative risks of 0.67 for 0–30 days (p<0.001), 0.76 for 30–60 days (p<0.01), 0.74 for 60–90 days (p=0.02), and 0.72 for 90–120 days (p=0.02), each relative to the risperidone risk between 150 and 180 days. After 120 days, there were no longer significant mortality risk differences between any of the medications.

Additional Sensitivity Analyses

Two additional analyses were performed to further understand mortality risk differences. First, we explored whether the larger proportion of patients with Parkinson's disease in the quetiapine cohort may have resulted in a lower mortality risk. Patients with Parkinson's disease taking quetiapine tended to receive lower quetiapine dosages and had less medical burden than patients without Parkinson's disease but were more likely to have depression. However, after covariate adjustment, patients with Parkinson's disease actually had higher mortality rates than patients without Parkinson's disease in the quetiapine cohort (relative risk=1.39, 95% CI=1.18–1.64, p<0.001).

Second, we examined haloperidol's role as the agent with the highest mortality by comparing information about haloperidol and risperidone users after individually matching each haloperidol patient with up to two risperidone patients. Variables included age, site of care (psychiatric or nonpsychiatric setting), race, and medical comorbidity (Charlson comorbidity index, presence of delirium diagnosis, and inpatient hospitalization in the preceding year). This analysis was based on 2,757 patients (1,056 patients taking haloperidol and 1,691 matched patients taking risperidone) and showed that haloperidol users were at a higher risk of mortality than risperidone users, with an adjusted relative risk of 1.45 (p=0.06) for the exposure analysis and 1.57 (p<0.001) for the intent-to-treat analysis.

Finally, a true intent-to-treat analysis (which included patients who subsequently switched from their initial medication, N=38,617) did not yield different conclusions from the main analyses: haloperidol users had the highest covariate-adjusted mortality rates (relative risk=1.50, 95% CI=1.35–1.67) followed by olanzapine users (relative risk=1.02, 95% CI=0.92–1.12), risperidone users (reference), valproic acid and its derivatives users (relative risk=0.95, 95% CI=0.82–1.10), and quetiapine users (relative risk=0.76, 95% CI=0.70–0.82).

Discussion

In this large national sample of outpatients with dementia newly started on antipsychotic drugs or valproic acid and its derivatives, we examined differences in mortality among individual agents. Consistent across analyses was the finding that haloperidol had the highest mortality risk and quetiapine the lowest. The mortality risk for valproic acid and its derivatives, which were included as a nonantipsychotic comparison, was generally higher than the risk for quetiapine and similar to that for risperidone. Across all medications other than haloperidol, the mortality risk was found to be 1.5 times higher on average in the first 120 days than for the subsequent period; for haloperidol, the risk was highest in the first 30 days, and then it significantly and sharply decreased.

Haloperidol's association with the highest mortality risks in this study is not surprising and confirms previous findings. Observational studies have reported that conventional antipsychotics as a group are associated with higher mortality risks than atypical antipsychotics (

8,

14). In addition, Schneider and colleagues' meta-analysis of atypical antipsychotics (

2) showed haloperidol to have a higher risk of mortality compared with placebo (relative risk=1.68) than did atypical antipsychotics (relative risk=1.54). The relationship between haloperidol and mortality may be confounded by selection issues and underlying user characteristics, particularly given secular trends in which atypical antipsychotics largely replaced conventional antipsychotics in the 1990s (

10,

18,

19). The shift from conventional to atypical antipsychotics during this period is thought to be because of efficacy evidence from early clinical trials, perceived safety advantages, and published expert consensus guidelines (

20). In our sample, patients taking haloperidol were older, sicker (highest Charlson comorbidity index, most inpatient days, and highest concurrent delirium diagnoses), and more likely to be African American than patients taking atypical antipsychotics. After controlling for those confounding factors, the haloperidol-associated risks remained significant, although it should be noted that the main risk of mortality with this agent appeared to be in the first month of treatment, with a rapid decrease in mortality over time. The majority of haloperidol users (approximately 78%) received their prescriptions at nonpsychiatric visits. This finding, paired with the likelihood of haloperidol being used for delirium in inpatient settings but possibly being counted on discharge in observational data as a “new prescription,” might again suggest that the mortality difference could be influenced by unmeasured medical confounders such as unrecorded delirium episodes. However, our sensitivity analysis matched users of haloperidol to users of risperidone (chosen as the most relevant clinical comparison) using variables including age, race, medical comorbidities, and site of prescription (psychiatric or nonpsychiatric setting) but did not corroborate this concern. Here, although only marginally significant because of the reduction in sample size from matching, haloperidol showed a greater mortality risk over risperidone (relative risk=1.45).

What about differences in risk among the atypical antipsychotics? A recent case-control study (

9) comparing information about antipsychotic users with nonusers found that quetiapine was not associated with short-term increases in mortality, while the other atypical antipsychotics studied were. The study did not directly compare antipsychotics to each other to assess differential risk among these agents. Additionally, the comparison of antipsychotic users to nonusers may have been problematic, as the underlying behavioral and frailty issues prompting medication use may be linked inextricably with mortality and may substantially overestimate the mortality risks of antipsychotics (

21). Using a variety of approaches to control for potential selection bias, our cohort study focused on head-to-head antipsychotic comparisons to examine differential risks among the atypical agents.

We found that quetiapine had the lowest risk of mortality across all analyses. Quetiapine is often prescribed in low dosages for its sedative/hypnotic properties; thus, we also performed analyses controlling for antipsychotic dosage. In these analyses as well, quetiapine was significantly associated with lower risk. It is not clear why quetiapine would have a lower risk than the other atypical antipsychotics, but it may be partially related to its receptor or side effect profile. A significantly higher proportion of patients taking quetiapine had Parkinson's disease; however, our sensitivity analyses did not indicate that this was a likely explanation for quetiapine's lower mortality risk. An alternative explanation might be patient selection: perhaps those with milder dementia or behavioral disturbances receive prescriptions for quetiapine. There is no rapid-acting form of quetiapine as there are for other atypical antipsychotics, so this agent is less likely to be used in urgent situations.

In most analyses, the mortality risk for valproic acid and its derivatives was higher than that for quetiapine but no different from that for risperidone or olanzapine. The use of valproic acid and its derivatives as an alternative to antipsychotics in addressing neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia may not be without other risks as well. Studies have linked anticonvulsant use in the elderly with fracture (

22), somnolence, and thrombocytopenia (

23). In addition, although valproic acid and its derivatives have been touted for behavioral stabilization and even potential neuroprotection, the evidence is lacking for such efficacy (

24,

25).

The greatest mortality risk for haloperidol was seen within the first 30 days; for the other medications, the risk was higher in the first 120 days than in the subsequent period. The exposure period for haloperidol was considerably shorter than for the other agents, and the haloperidol result may be related in part to its use in older and sicker patients. A number of these patients may have started this agent during an inpatient stay for delirium or in nonpsychiatric settings. There are several clinical implications of a greater mortality risk for atypical antipsychotics and valproic acid and its derivatives in the first 4 months of treatment than in subsequent months. First, if these agents are prescribed, then they should be used in conjunction with a risk-benefit approach (

26,

27) with consideration for the efficacy and safety evidence base for each agent (

2–

4,

6,

20,

26). Second, patients should be monitored during the acute treatment period for adverse effects and reactions. Finally, periodic attempts at discontinuation should be made, particularly in light of the results from the Dementia Antipsychotic Withdrawal Trial (DART-AD). In DART-AD (

5), the investigators randomly assigned patients with dementia to antipsychotic continuation (the majority taking risperidone [67%] or haloperidol [26%]) or antipsychotic discontinuation and placebo and observed a significantly higher mortality rate for patients continuing antipsychotics. The difference in duration of mortality risk for antipsychotics between DART-AD (>12 months) and our study (≤120 days) may be related to differences in exposure periods and study samples.

The use of administrative data for pharmacoepidemiologic research has several limitations. Prescription fills can be an imprecise measure of actual drug exposure as they may not reflect day-to-day usage. Data on dementia severity were also lacking, although not accounting for this confounder may actually contribute to an underestimation of the mortality risk of haloperidol (

21). Finally, while the large, integrated VA health system offers us the opportunity to examine pharmacoepidemiologic changes, the findings may not be completely generalizable. Consistent with the demographic characteristics of the VA patient population, the study cohort was primarily male. However, our data and other national data have striking similarities on many important variables that might affect provider antipsychotic prescribing practices (e.g., race and the prevalence of key psychiatric and medical conditions [

28,

29]). Finally, the issue of concurrent delirium in dementia is also an important one, and as with other observational studies, we used diagnostic codes to denote the presence of delirium. Given the lack of recognition of delirium in many cases, underdiagnosis is a problem; however, we have no evidence to suggest that such underdiagnosis varies by antipsychotic agent. Despite these limitations, we used various analytic methods and our results consistently indicated differences in mortality risks among individual antipsychotic agents. Further, the use of valproic acid and derivatives as alternative agents to address the neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia may carry associated risks as well.