Young people with a first episode of psychosis are at high risk of developing chronic schizophrenia, arguably the most disruptive of mental illnesses. Psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations, delusions, disorganized thoughts, and negative symptoms profoundly influence quality of life, relationships, and daily functioning. At least 50% of schizophrenia patients continue to experience psychotic symptoms more than 10 years after onset (

1,

2). Furthermore, approximately 15% of schizophrenia patients display deficit pathology (i.e., syndromes characterized by chronic negative symptoms and poor outcome), and the proportion rises to 25%–30% in more chronic populations (

3,

4). Mortality through suicide in schizophrenia patients has a lifetime risk of 4.9% (

5). The cost of the disorder is substantial, as it largely affects young adults at the start of their careers and relationships. Between 63% and 86% of patients have no regular employment and are socially and functionally impaired after 10 years or more (

6–

10). Relative to the general population, schizophrenia patients are seven to 10 times more likely to be single 10 years after first admission (

11).

Most factors influencing course or prognosis such as gender, age at onset, mode of onset, and type of symptoms, are wholly or partly endogenous. One of the few malleable prognostic factors is the duration of untreated psychosis, which is defined as the time between the onset of the first psychotic episode and the start of first adequate treatment. Meta-analyses have concluded that a prolongation of this interval is significantly correlated with poorer symptomatic and functional outcomes (

12,

13). However, causality in this association has not been clearly delineated or separated from endogenous factors. To do so, it is necessary to manipulate the duration of untreated psychosis and assess subsequent outcomes (

14). The Treatment and Intervention in Psychosis (TIPS) early-detection study was designed to reduce this duration and to study the effects of the reduction on the course and outcome of psychosis. The characteristics of patients from a health care area practicing intensive and comprehensive early detection of psychosis were compared with those of patients from a comparison area practicing the usual methods of detection. In the early-detection area, the duration of untreated psychosis was reduced from a median of 26 weeks to 5 weeks (

14), while the usual-detection area had a median of 16 weeks (

15). Patients from the early-detection area had fewer positive and negative symptoms at presentation, at 2 years, and at 5 years, and they had fewer negative, cognitive, and depressive symptoms at 2 and 5 years.

In this article, we present the 10-year follow-up to these original findings. Comparing long-term outcomes in psychosis remains a challenge because substantially different outcome criteria have been used across studies and include the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF) (

7,

9,

16,

17), individual symptom dimensions (

18), psychotic symptoms as a whole (

7), and different definitions of symptom remission (

19–

21). The Remission Working Group (

22) introduced standardized symptom remission criteria and suggested that symptom state be combined with functional criteria to make one standard outcome measure labeled “recovery” (

23). Level of functioning has implications for quality of life, mental health care dependency, and income (

24,

25).

Several studies have investigated functional outcome. Bottlender et al. (

6) observed that 20% of schizophrenia patients had no impairment in work role behavior 15 years after illness onset. In the Chicago follow-up study (

8), 19% of schizophrenia patients assessed at 15 years had worked more than half time in the previous year and had low symptom levels. In the International Study of Schizophrenia, 16% of patients were labeled as recovered both symptomatically and functionally at 15-year follow-up (

7). A 15-year substudy found that 14% of patients had no social disability and worked full time (

10). Similar figures were found in Nottingham, U.K. (follow-up at 13 years); Sofia, Bulgaria (16 years); and Manchester, U.K. (10 years); positive results ranged from 14% to 21% (

9,

16,

26).

We adopted the Andreasen et al. remission criteria (

22) and combined them with a standardized functional outcome measure based on the Strauss-Carpenter Level of Function Scale (

24). We assessed whether differences in symptom levels between early- and usual-detection areas would be maintained at 10-year follow-up and whether patients from the early-detection area would have higher rates of recovery.

Method

The TIPS study used a quasi-experimental design, and four Scandinavian health care sectors participated. Two sectors in Rogaland County, Norway, which had implemented an early-detection system for psychosis, made up the early-detection area (approximate population, 370,000). The Ullevaal Health Care Sector in Oslo County, Norway, and the mid-sector, Roskilde County, Denmark, made up the usual-detection areas (approximate combined population, 295,000). The areas were similar in sociodemographic characteristics (urbanicity and mean educational and income levels) and opportunities for employment (

25). The early-detection program combined information campaigns about psychosis with easy access to mental health care. It is described in detail elsewhere (

15,

16). Patients from both areas were treated according to a 2-year standard treatment protocol that included antipsychotic medication, supportive psychotherapy, and multifamily psychoeducation.

The cohort was recruited between 1997 and 2001. The inclusion criteria, described in detail elsewhere (

25), were first-episode schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, or schizoaffective disorder (core schizophrenia), delusional disorder, mood disorder with mood-incongruent psychotic features, brief psychotic disorder or psychosis not otherwise specified, living in one of the participating sites, and being 18–65 years old and within the normal range of intellectual functioning (WAIS-R-based IQ estimate >70). All study participants gave informed consent. Of eligible patients, 23% declined to participate. Those who declined had a longer duration of untreated psychosis on average (32 weeks compared with 10 weeks, p<0.00) and were slightly older on average (30.4 years old compared with 28.1 years old, p=0.05). There was no significant difference between the early-detection and usual-detection areas in number of patients who declined or their duration of untreated psychosis, which minimized the risk of biased comparison. At all sites, health care services were based on catchment area and were publicly funded. An original sample of 281 patients entered the study.

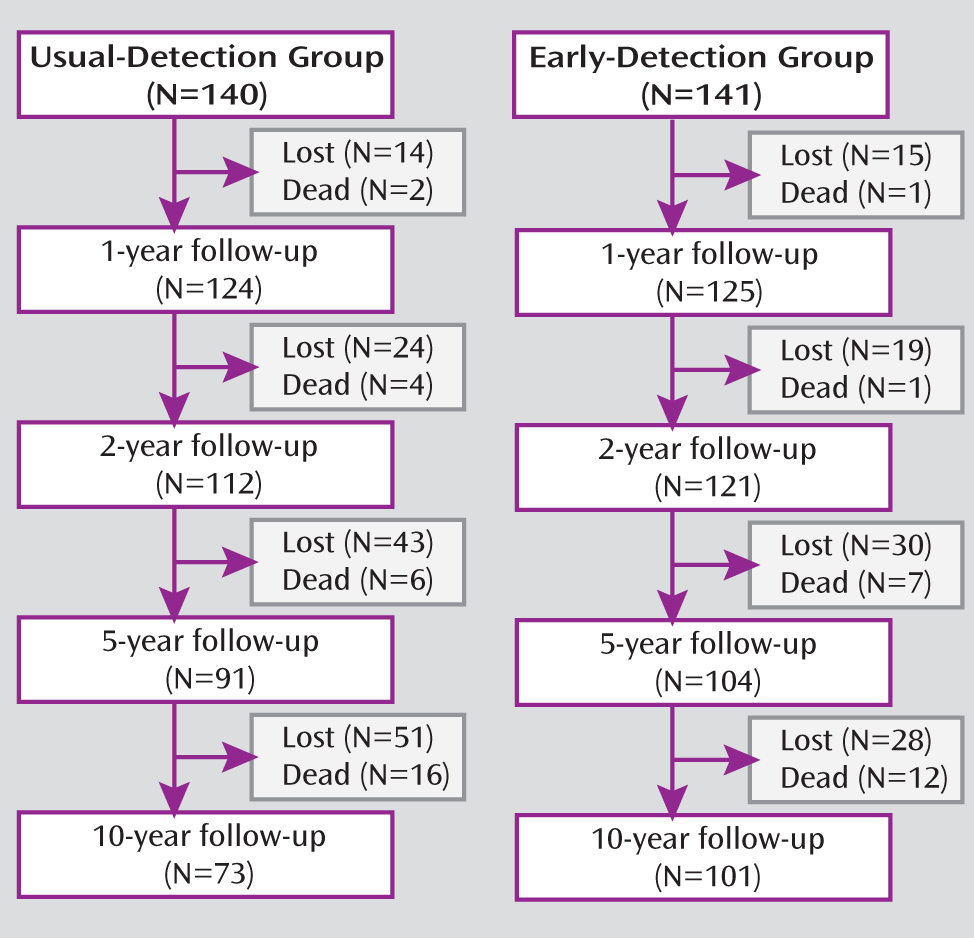

Figure 1 provides an overview of the flow of participants through follow-ups at 1, 2, 5, and 10 years.

Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of patients with and without 10-year follow-up. Between patients in the 10-year follow-up group and patients lost to follow-up, there were no differences in age, score on the GAF, diagnostic distribution, or substance abuse at enrollment. In the early-detection area, there were fewer males in the 10-year follow-up group than in the group lost to follow-up (odds ratio=0.4, 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.2–0.8, p=0.026), and patients lost to follow-up had a significantly longer median duration of untreated psychosis (p=0.006). Twelve patients in the early-detection area and 16 in the usual-detection area had died. These were included in the “lost” group as there were no significant baseline differences on any of the variables between dead patients and surviving patients who were lost to follow-up. The Regional Committee for Research Ethics Health Region East and the Regional Committee for Science Ethics Region Zealand approved this study.

Assessments were carried out at baseline, 3 months, and 1, 2, 5, and 10 years. Symptom levels were measured by the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS;

27,

28). Duration of untreated psychosis was measured as the time in weeks from emergence of the first positive psychotic symptoms (PANSS score of 4 or more on positive scale items P1, P3, P5, or P6 or on general scale item 9) to the start of the first adequate treatment of psychosis (i.e., enrollment in the study). Ten-year assessments were conducted by specialized health personnel (one psychiatrist [U.H.], one clinical psychologist [W.t.v.H.], and one psychiatric resident [J.E.]). The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (SCID) was used for diagnostic purposes (

29), and the level of functioning was assessed using the GAF. GAF scores were split into symptom and function scores (

30).

Symptom remission was defined in accordance with the new international standardized criteria (

22); patients could not score 4 or higher for the past 6 months on any of the following PANSS items: P1 (delusions), P2 (disorganized thought), P3 (hallucinatory behavior), N1 (affective flattening), N4 (passive social withdrawal), N6 (lack of spontaneity), G5 (bizarre posture), or G9 (unusual thought content). Fulfilling these criteria indicated symptom remission. Social functioning was measured by the subscales measuring work and social interaction of the Strauss-Carpenter Level of Function Scale (

24) and the criteria of living independently: day-to-day living (independent living), role functioning (work, academic, or full-time homemaking), and social interaction. A score of 0 indicated very poor functioning and 4 indicated adequate functioning for the total period of the previous 12 months. A score of 4 in all three subscales indicated adequate functioning. Recovery was operationalized as a single variable of “yes” for all patients who met criteria for both symptom remission and adequate functioning. Thus, all patients who met the two criteria had been in remission for at least 12 months.

Reliability was assessed throughout the study, and results have been published in previous articles (

15). The reliability was satisfactory for all measures. For diagnosis, kappa was 0.81, and intraclass correlation coefficients (one-way random-effects model) were 0.86 for GAF function scores and 0.91 for GAF symptom scores.

At 10 years, the raters were trained using videotaped interviews and vignettes, and cases were discussed regularly to avoid drift. Twenty-six patients gave informed consent for video recording of the PANSS interviews (seven in the early-detection group and 19 in the usual-detection group).The PANSS or GAF scores of the videotaped patients were not significantly different from those of patients who were not videotaped. The videotapes were rated by an experienced psychologist not involved in the project who was blind to all ratings; however, because of differences in dialects between sites, full blinding was not possible. For the five PANSS components, the intraclass correlations ranged from 0.61 to 0.82. For the GAF, the intraclass correlations were 0.83 for symptoms and 0.88 for function.

The statistical analyses were conducted using the Predictive Analytics SoftWare package, version 18.0 (

31), and the R program, version 2.10.0 (

32). There may have been selective attrition at 10-year follow-up, which had to be taken into account in data analysis. First, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied to investigate the possibility of an interaction between type of symptoms at last follow-up and early- or usual-detection group dropout. Second, data from continuous outcome variables (PANSS and GAF scores) were analyzed using linear mixed-effects models. We used symptom scores as dependent variables, and we used health care sector, time, and their interaction as independent variables, exploring illness courses in early-detection and usual-detection areas and differences between them. Estimates were corrected for possible effects of the covariates gender, age, and duration of untreated psychosis, the latter being log-transformed to obtain less spread in the distribution. Data on clinical measures at baseline induced a clear nonlinearity and were excluded. In addition to the linear mixed-effects analyses, group differences were estimated using independent-samples t tests for continuous variables and odds ratios for categorical variables. Nonparametric analyses (Mann-Whitney U test) were applied for comparison of skewed data, and all tests were two-tailed. We made a single test on recovery as our main outcome measure. Ten additional tests on symptom outcome, GAF, and treatment and three tests on social functioning were carried out on specific outcome measures. Bonferroni-corrected alpha values were calculated in the case of multiple comparisons on symptoms and function. No Bonferroni correction was made for the measure of recovery, as this is a single variable. Finally, logistic regression analysis was applied to assess which factors predicted recovery. A stepwise variable selection routine was employed with PANSS symptom domains at baseline and age, gender, duration of untreated psychosis, and early- or usual-detection area as candidate predictor variables.

Results

Table 2 summarizes the outcome scores observed at 10 years for the PANSS symptom components and GAF scores across the early- and usual-detection areas. There were no significant differences in treatment (defined as still using antipsychotics and attending psychotherapy at least once a month), although the study's standard treatment protocol was used for the first 2 years only. For the 10-year follow-up, significantly more surviving patients were recruited from the early-detection area (78.3%, N=129) than from the usual-detection area (58.9%, N=124) (odds ratio=2.5, 95% CI=1.5–4.4, p=0.001). An ANOVA of 5-year symptom levels showed significant interaction effects between dropping out and usual-detection area for the negative (p=0.016) and cognitive (p=0.031) components. This indicates that the patients dropping out at 10 years in the usual-detection area had higher symptom levels than dropouts in the early-detection area.

Linear mixed-effects models estimated no significant differences between the two areas at 10 years on any PANSS component except for excitative symptoms (p=0.002), with higher scores in the early-detection area mainly because of higher scores in many patients who had not recovered. These models estimated a significant main effect over time of being from the early-detection area for the negative, cognitive, and depressive PANSS components.

Furthermore, the models suggested nonparallel illness courses in the two areas on positive, negative, cognitive, and excitative components (time by early-detection area, p<0.05 in all cases). Early-detection symptom levels were estimated to have been lower than usual-detection symptom levels up until the 10-year follow-up, when differences disappeared or, in the case of excitative symptoms, were reversed. This effect was significant for all but the depressive component. However, linear mixed-effects modeling assumes random attrition, whereas in our sample attrition seems to have been selective. We found no fully satisfactory way of accounting for this and deduce that firm conclusions about symptom levels are unwarranted.

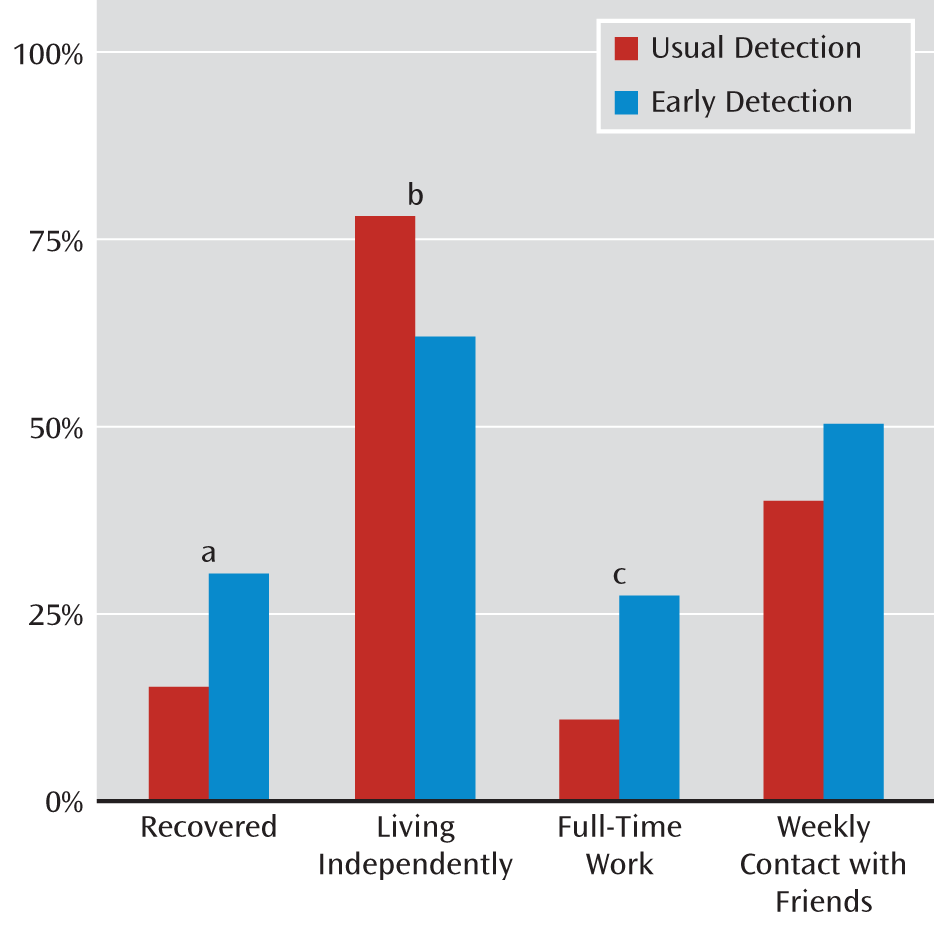

A significantly higher number of early-detection patients fulfilled recovery criteria (30.7% compared with 15.1%) (

Figure 2). Although remission rates were evenly distributed across the areas (47.9% in the usual-detection area compared with 52.5% in the early-detection area; odds ratio=1.20; 95% CI=0.66–2.19), a significantly larger proportion of patients in the early-detection area had full-time employment (27.7% compared with 11.0%), thus fulfilling recovery criteria. There were no significant differences between groups in the amount of social contact with friends. More patients in the early-detection area lived independently (78% compared with 62%); however, living independently does not imply recovery. Only 17.9% of the patients living independently in the usual-detection area were fully recovered, compared with 48.4% for early-detection patients.

In the logistic regression, both forward and backward selection identified early-detection area (p=0.019), PANSS negative symptoms (p=0.005), and PANSS depressive symptoms at inclusion (p=0.06) as predictors of recovery. Thus, being from the early-detection area predicted recovery (odds ratio=2.7, 95% CI=1.2–6.2), as did having fewer negative symptoms at inclusion (odds ratio=0.92, 95% CI=0.9–1.0) (

Table 3). When early-detection area was entered into the model, age, duration of psychosis, and PANSS symptom components other than the negative and depressive components were excluded for low contributions. The depressive component's contribution was not significant, however.

Of those recovered, seven patients (63%) in the usual-detection area and 17 patients (55%) in the early-detection area received a diagnosis of core schizophrenia spectrum disorder at the 10-year follow-up. No relation between being recovered and being diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorder was found (odds ratio=0.7; 95% CI=0.2–2.9).

Discussion

This study produced three main findings. First, selective attrition occurred; more patients with higher negative and cognitive symptom levels dropped out in the usual-detection area than in the early-detection area. Second, differences in negative, cognitive, and depressive components from 1, 2, and 5 years were not maintained at 10 years. The early-detection area had significantly higher excitative symptom levels among patients who did not recover. Third, the early-detection area had significantly higher rates of recovery in spite of the selective loss of patients with lower symptom levels.

A skewed loss of patients was observed despite identical retention procedures in both areas. The greater participation of early-detection patients may have been related to the early-detection program with its focus over many years on recognizing psychotic illnesses coupled with easier access to care. Such attention and persistence may have engendered greater rapport with patients and their families. The early-detection program was implemented from 1997 to 2000. A 4-year period without intensive information campaigns followed study recruitment, but the full program was resumed in 2005 and has been active since. Perhaps easy access to mental health care for patients also meant easy access to patients for this study. It has also been noted that a longer duration of untreated psychosis can negatively influence recruitment to studies (

33). In our sample, treatment delay was longer for those who declined than for those who participated, and a longer duration of untreated psychosis predicted study dropout at 10 years.

We observed a tendency for symptom levels in the usual-detection group, which were initially more severe, to improve over time, with the symptom levels in the early-detection group (initially milder) not changing significantly. The model could not, however, fully account for the nonrandomness of the study sample attrition. Hence, it should be considered with caution, especially since similar trends were not observed at any of the other follow-ups at 1, 2, and 5 years, at each of which the early-detection sample was significantly less impaired with deficit psychopathology. Also, the median duration of untreated psychosis of 16 weeks in the usual-detection area was shorter than in most other studies that had been published at that time (

12,

13), possibly raising the threshold for demonstrating differences in symptom severity between the areas. It could also mean that active psychosis in its early phase may be more progressive than is realized.

The early-detection recovery rate of 30% was relatively high compared with recovery rates from other studies of first-episode psychosis (

6,

7,

34). This finding was of particular interest considering our strict definition of recovery, which required both stable symptomatic remission and intact functional capacity for at least 1 year.

It may seem paradoxical that the logistical regression analysis of recovery did not include duration of untreated psychosis as a predictor while coming from the early-detection area did. This could be explained by the fact that early detection of psychosis is not simply equal to short duration of psychosis. Early detection not only establishes a detection system but also provides a lower threshold for entering treatment irrespective of the duration of untreated psychosis (i.e., patients do not need to display frightening suicidality or dramatic symptoms to be “allowed” into the treatment system). Furthermore, fewer negative symptoms at baseline also predicted recovery. It is well known that negative symptoms are linked to functional outcome (

35), and higher recovery rates in the early-detection area may suggest that the sustained lower levels of negative symptoms over the first 5 years have a prolonged influence on outcome.

Our results seem to contain a second paradox: early-detection patients displayed more severe excitative symptoms, but at the same time, they had higher recovery rates. However, few studies have related outcome to excitative symptoms, and none have found any association. Excitative symptoms represent the opposite of negative symptoms in many ways, with hyperactivity and poor impulse control being two of the five items. We previously published data indicating a negative association between excitative symptoms and 2-year remission (

36).

In conclusion, we believe these findings have clear and immediate treatment implications, namely, that early detection and intervention in psychosis with standard treatments confers a significant and lasting advantage for a considerable group of patients with first-episode psychosis. Why this may be so remains speculative, but these 10-year results suggest that active early treatment of psychosis may truncate the severity and progression of the disorder's symptomatic and dysfunctional manifestations. The findings indicate that early detection and intervention in psychosis can have positive prognostic implications for the disorder, especially for its deficit psychopathologies and functional decline, and that this result can be lasting and perhaps permanent.

Limitations of this study include nonparticipation and dropout. Of the eligible patients, 23% declined to participate at baseline, and 38% of the patients who gave informed consent were lost to follow-up by 10 years, including those who died. This represents a loss of valuable information and may weaken the validity of the findings. The attrition at the 10-year follow-up was selective and may have masked other findings. The fact that the early-detection area had higher recovery rates despite more severely ill patients dropping out in the usual-detection area, however, strengthens the link between duration of untreated disorder and deterioration. Finally, this is one of the few epidemiological samples of clearly defined first-episode psychosis that was followed for as long as 10 years. It is also the first long-term follow-up study of first-episode psychosis to employ the new international standard remission criteria.