Fear is an adaptive response that has evolved to provide protection from potential harm in the environment. But when fear is excessive and disproportionate to the situation, it can lead to the development of an anxiety disorder. The current lifetime prevalence rate for anxiety disorders is 25% in developed countries (

1), and the World Health Organization (

2) predicts that by 2020 anxiety and depressive disorders combined will constitute the second greatest illness burden globally. Even more concerning is that despite an increase in the rate of individuals receiving treatment, there has been no decrease in prevalence rates (

3). Traditional drug treatments for anxiety, such as benzodiazepines and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, offer symptom relief, but relapse after treatment has ended is common. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is the most effective evidence-based psychological treatment for anxiety disorders. A major component of CBT is exposure therapy, which involves gradually exposing the individual to the feared stimulus or outcome in the absence of any danger. Although CBT is successful for many, not all patients achieve complete recovery with this treatment, and some fail to maintain treatment gains when assessed after longer intervals (

4,

5). This situation has prompted the comment that “a therapeutic impasse” has been reached and that further progress in enhancing current treatments will be made only after we have gained a deeper understanding of the neural mechanisms underlying fear and its reduction (

5).

In line with this view, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) recently proposed that mental health disorders should be viewed as disorders of brain circuitry, biomarkers of which may be detected using current and emerging tools in clinical neuroscience. It is NIMH's hope that conceptualizing mental disorders in this way will foster advances in the early detection of vulnerability to such disorders, as well as advances in predicting treatment response. Furthermore, it is hoped that treatments will eventually be tailored to meet the specific idiosyncrasies (both biological and psychological) of the individual. To meet this aim, NIMH proposes that rather than adhering to strict diagnostic categories (and determining research samples using this method), research should focus on identifying the fundamental underlying mechanisms of dysfunction across the various mental health disorders (

6). To this end, anxiety disorders would be conceptualized not as distinct diagnostic categories but as disorders of fear circuitry or of fear extinction or inhibition.

Advances in neuroimaging have permitted increasing specificity in the investigation of the neural basis of anxiety disorders. Such studies have investigated neural activity in individuals with anxiety disorders during a variety of conditions, including resting state, symptom provocation, and cognitive activity in a range of mental tasks. In general, research has implicated the amygdala, hippocampus, insula, anterior cingulate cortex, and ventromedial prefrontal cortex as regions of interest across anxiety disorders (

7,

8,

9). However, results regarding the specific neural regions implicated, as well as the direction of difference in neural activity in such regions, have been disparate both across and within diagnostic categories (

8). This disparity is likely a result, at least in part, of the fact that different studies employ widely different tasks during functional neuroimaging that tap into a variety of functions—emotion detection, affect regulation, fear processing, fear inhibition, and so on.

In this review, we begin with a brief overview of the neural circuits of fear conditioning and extinction and a summary of some recent findings on fear extinction in psychiatric disorders. We then propose that fear extinction is a good candidate model that can be used to examine the fundamental underlying mechanism of dysfunction across anxiety disorders. To support this proposition, we provide an overview of the advantages of using the fear extinction model to this end. We then assess how well the fear extinction model meets the criteria outlined by NIMH regarding its potential as a means to identify a fundamental biomarker of anxiety that can be used as a diagnostic tool, to predict vulnerability and treatment response, and to translate laboratory findings into clinical practice.

Why Study Fear Extinction in Anxiety?

In the laboratory, fear is acquired when a neutral conditioned stimulus (e.g., a light or tone) is paired with an aversive unconditioned stimulus (e.g., a mild shock). After several such pairings, the subject learns that the conditioned stimulus predicts the unconditioned stimulus, and subsequent presentation of the conditioned stimulus elicits a variety of fear responses, including freezing in the rodent and skin conductance responses in the human. Once acquired, fear to the conditioned stimulus can be extinguished by repeatedly exposing the subject to the conditioned stimulus in the absence of any aversive outcome. During extinction training, the subject's fear responses gradually decline, and when tested the following day, the subject typically exhibits long-term extinction recall.

The fear conditioning and extinction model has been used extensively to examine the neurobiology underlying fear processes in animals and more recently in humans. It is important to note that the fear conditioning model does not necessarily model the etiology of anxiety disorders, as most individuals with anxiety disorders cannot recall a specific conditioning episode that precipitated the disorder (except in posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD], in which the occurrence of a traumatic event is specified in the diagnostic criteria [

10]). The advantage of the fear conditioning model, however, is that it produces the behavioral symptoms commonly exhibited in anxiety disorders (e.g., avoidance) and thus can be used to test ways of reducing these symptoms, such as via extinction. We argue that the fear extinction model is suited to examination of potential biomarkers of anxiety for several reasons. First, a key feature of clinical anxiety disorders is a failure to appropriately inhibit, or extinguish, fear (

11). Individuals with anxiety disorders avoid fear-provoking situations and stimuli or endure them by employing a range of “safety behaviors” designed to protect the individuals from harm. Avoidance and the use of safety behaviors prevent the individual from challenging his or her unrealistic beliefs and thus prevent fear extinction. Hence, the fear extinction model provides a direct measure of what is widely accepted to be a central underlying dysfunction in anxiety disorders. As such, the measurement of neural activity during extinction may provide a sensitive measure of the neural circuitry involved in the maintenance of anxiety disorders.

Second, as noted above, exposure therapy is a dominant component of CBT. Even though anxiety disorders are characterized by dysfunctional cognitive processes (e.g., overestimation of the probability and cost of negative outcomes), research has shown that exposure therapy without explicit cognitive intervention is just as effective and invokes just as much cognitive change as comprehensive CBT that combines behavioral and cognitive interventions (

12). Exposure therapy was based on the extinction procedure used in animal studies of fear inhibition. Thus, in addition to potentially detecting the neural basis for the underlying dysfunction in anxiety disorders, extinction can also be used as a valid model of the most effective psychological treatment for anxiety disorders.

A third advantage of the fear extinction model is that comparison of animal studies and human neuroimaging studies suggests considerable similarity between the neural structures involved in extinction in the rodent and in the human, as reviewed in more detail below. The cross-species validity of the extinction model permits rodents to be used to address questions that are not possible to address using human subjects, such as trialing the effects of novel drugs on extinction and subsequent relapse, with the assurance that these findings are readily translatable to the human population.

The Fear Acquisition and Fear Extinction Circuitries

The neurobiology of fear acquisition is well characterized in rodents and humans (

13). Briefly, it is widely accepted that the basolateral complex of the amygdala is the main neural structure in which information about conditioned and unconditioned stimuli converge. This finding has been supported by studies in rodents using lesions, pharmacological inactivation, electrophysiology, and drug antagonists, which together have demonstrated that interfering with normal functioning of the basolateral amygdala disrupts the acquisition and expression of fear conditioning (

14). There is also evidence from rodent studies that the prelimbic division of the medial prefrontal cortex is involved in regulating the expression of learned fear. Inactivation of the prelimbic cortex reduces the expression of cued and contextual fear (

15), while microstimulation increases conditioned freezing and reduces extinction (

16), prompting the assertion that the prelimbic cortex regulates fear expression by activating the amygdala. This view is supported by findings that prelimbic neurons potentiate their response to a tone-conditioned stimulus and that extinction failure is associated with a persistence of prelimbic neuronal response after extinction training (

17). Functional MRI (fMRI) studies have demonstrated that humans show robust increases in activity in the amygdala and the dorsal anterior cingulate (which appears to be functionally analogous to the prelimbic cortex) during fear acquisition and expression (

18,

19). Other research (

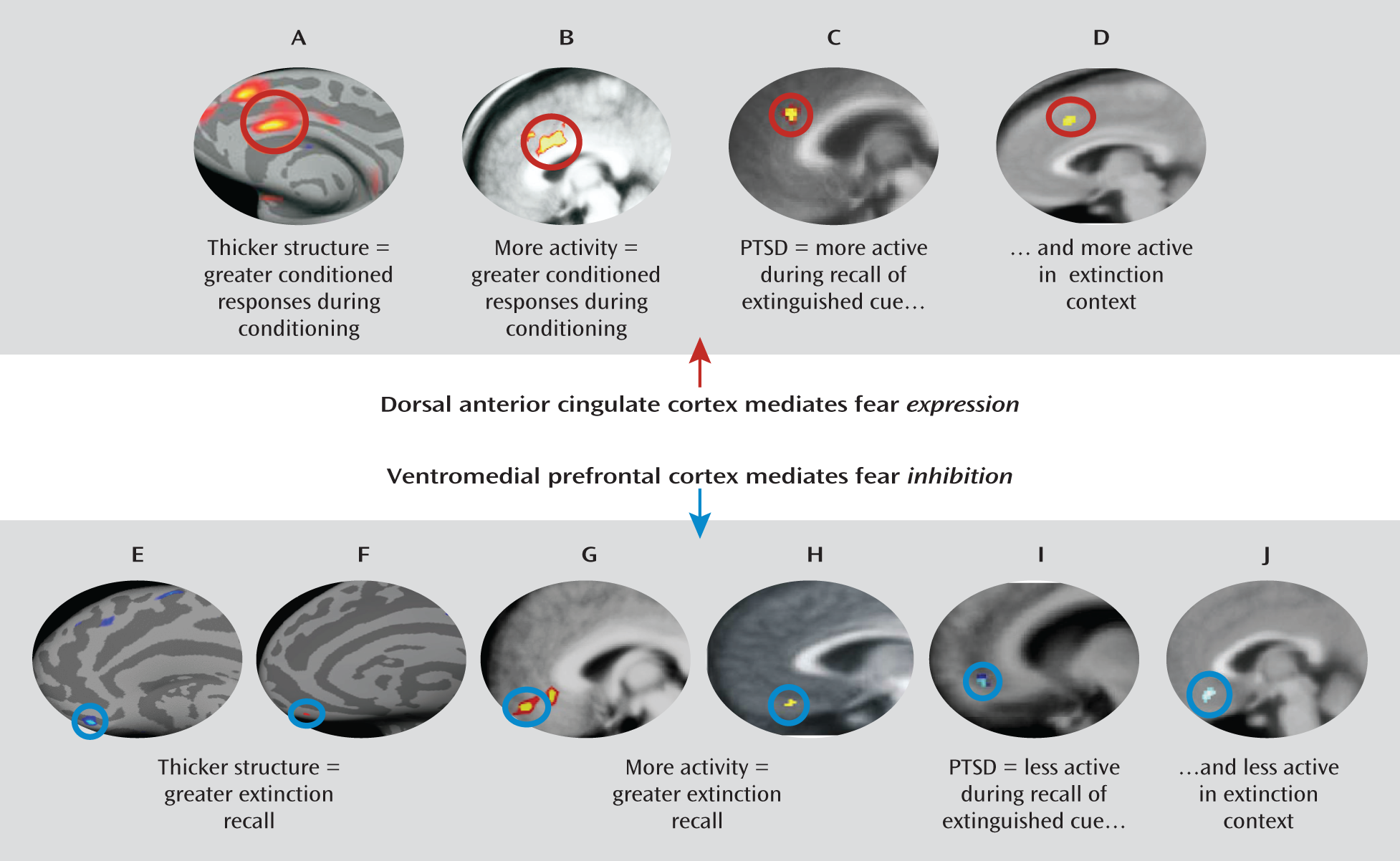

20) has demonstrated that in healthy humans, the cortical thickness of the dorsal anterior cingulate is positively correlated with skin conductance responses during fear conditioning acquisition and that activation of this structure during acquisition of conditioning increases in response to a stimulus paired with shock relative to a stimulus not paired with shock. It should be noted, however, that a recent study failed to replicate the correlation between the cortical thickness of the dorsal anterior cingulate and fear acquisition levels in healthy subjects (

21). In addition, other regions have also been implicated in fear expression in humans, including the insula, the thalamus, and brainstem regions such as the periaqueductal gray.

Fear extinction, on the other hand, involves interactions between the infralimbic region of the medial prefrontal cortex, the basolateral complex of the amygdala, and the hippocampus. It is proposed that when an extinguished cue is presented in the extinction training context, the hippocampus activates the infralimbic cortex, which in turn activates inhibitory interneurons in the basolateral amygdala that inhibit the output neurons in the central amygdala, thus preventing conditioned responding. In contrast, when the extinguished cue is presented in a context other than extinction training, the hippocampus does not activate the infralimbic cortex and central amygdala activity is not inhibited, and thus conditioned responding returns (

22).

Subsequent analysis of the neurobiology underlying fear extinction in humans using fMRI has revealed remarkable preservation of this circuitry across species. Earlier fMRI studies demonstrated that the amygdala exhibits increased activation to the conditioned stimulus during early extinction training, and this activation decreases across extinction training (

23). Other studies demonstrated that the amygdala and the orbitofrontal cortex (part of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex) exhibit increased activity during extinction training for an olfactory cue (

24) and that there are differences in amygdala and hippocampal activity during extinction training in comparison to a nonextinguished comparison group (

18). Later studies focusing on the neurobiology of extinction recall consistently demonstrated that extinction recall is associated with increased activity in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (

19,

25,

26), a structure that has been proposed to be the human homologue of the rat infralimbic cortex. Furthermore, it has been shown using structural MRI that extinction recall is positively correlated with the thickness of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (

21,

27,

28).

Several studies have also provided evidence for increased hippocampal activity during extinction recall (

18,

26). Furthermore, one study reported increased hippocampal and ventromedial prefrontal cortex activity during recall in the extinction context but not in the original conditioning context (

25). These findings support the notion that the hippocampus modulates when and where extinction is expressed, depending on the contextual information. Hence, there is much evidence to support the notion that a distinct neural circuitry involving interactions among the amygdala, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, and the hippocampus underlies the ability to extinguish fear and that this circuitry has been preserved across evolution.

In addition, a burgeoning literature is investigating the molecular signaling pathways within this neural circuitry that support the formation of extinction memories, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). In rodents, BDNF mRNA increases in the basolateral amygdala after extinction (

29), and BDNF infusions in the infralimbic cortex and the hippocampus enhance extinction (

30). Moreover, a BDNF genetic polymorphism alters fear extinction retention in both rodents and humans (

31,

32). Other signals that are involved in extinction and appear to have been conserved across evolution include neuropeptide Y (

33,

34) and cannabinoids (

35,

36). A full review of the molecular signals implicated in extinction is beyond the scope of this article, but several excellent reviews have been published in recent years (

37,

38).

Is Fear Extinction, or the Fear Extinction Circuitry, Altered in Anxiety?

It is widely accepted that anxiety disorders are maintained as a result of a failure to appropriately extinguish fear. In this section, we address two questions: 1) Do clinically anxious populations exhibit alterations in the neural circuitry that mediates normal extinction? and 2) Does the extinction model provide a sensitive measure of this dysfunction in clinical populations?

Evidence From Neuroimaging Studies Using Symptom Provocation

In general, the neural structures that are thought to mediate fear extinction have also been identified as structures of interest in symptom provocation studies, in which fear-relevant stimuli are presented to anxious and nonanxious individuals. For example, one study reported that blood flow in the medial frontal gyrus decreased in veterans with PTSD relative to trauma-exposed veterans without PTSD when both groups were exposed to trauma reminders and that medial frontal gyrus blood flow was inversely correlated with changes in amygdala blood flow (

39). The study also reported a positive correlation between changes in amygdala blood flow and symptom severity and a negative correlation between changes in medial frontal gyrus blood flow and symptom severity. Heightened amygdala activity (

40,

41) and diminished ventromedial prefrontal cortex activity (

41) while viewing fearful faces have also been reported in individuals with PTSD compared with trauma-exposed comparison subjects.

Findings similar to those for PTSD have been reported for specific phobia. For example, individuals with spider phobia exhibited increased amygdala, insula, anterior cingulate, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex activation when viewing spider-related compared with neutral images, a finding that was absent in nonphobic comparison subjects (

42). Another study (

43) examined brain activity using fMRI in individuals with spider phobia who were asked to voluntarily up- and down-regulate their emotions elicited by both spider imagery and nonphobic but generally aversive imagery, using a cognitive reappraisal strategy. Participants exhibited increased activity in the dorsal anterior cingulate and insula but reduced activity in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex when attempting to regulate emotional responses to spider imagery, whereas no such changes were observed during regulation toward aversive, phobia-irrelevant imagery. This result suggests that the same neural circuitry may regulate both automatic fear-inhibition tasks (laboratory fear extinction, where no explicit instruction to regulate emotions is given) and effortful fear-inhibition tasks (where an explicit instruction to regulate emotions is given). Furthermore, it suggests that there may be a deficit in this circuitry in populations with spider phobia.

Evidence From Neural Connectivity Studies

More recent studies have used imaging techniques to measure the strength of connectivity between the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and the amygdala and to correlate this with anxious traits. For example, a study using diffusion tensor imaging (

44) showed that the strength of the reciprocal connections between the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex predicts trait levels of anxiety, such that the weaker the pathway, the greater the level of trait anxiety. Another study (

45) reported that amygdala resting state activity was positively coupled to ventromedial prefrontal cortex activity in individuals with low anxiety levels and negatively coupled to ventromedial prefrontal cortex activity in those with high anxiety levels. Together, these studies suggest that dysfunctions in connectivity between the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and the amygdala may mediate susceptibility to anxiety disorders.

Evidence From Neuroimaging Studies of Treatment Outcome

Another way to address the question of whether dysfunctions in the neural circuitry of extinction underlie anxiety disorders is to determine whether successful recovery is correlated with changes in this neural circuitry. Indeed, one session of intensive exposure therapy has been shown to reduce amygdala, dorsal anterior cingulate, and insula hyperactivation in response to viewing phobia-relevant stimuli in individuals with spider phobia, as measured 2 weeks after exposure (

46). Another study (

47) reported reduced hyperactivity in the anterior cingulate and the insula after CBT for spider phobia relative to a waiting list comparison group. Decreases in anterior cingulate blood flow and increases in ventromedial prefrontal cortex blood flow have been reported to occur after CBT in panic disorder (

48). These effects do not appear to be restricted to CBT, as similar neural changes have been reported to occur after pharmacological treatment for social phobia (

49). The latter study reported a comparable decrease in regional cerebral blood flow in the amygdala and the hippocampus after successful treatment with citalopram or CBT. This finding suggests that successful pharmacological and psychological treatments may in some cases target the same dysfunction in the neural circuitry underlying extinction.

Evidence From Psychophysiological and Behavioral Studies

Several studies have directly measured fear inhibition ability in clinically anxious populations using laboratory extinction tasks. These studies have consistently demonstrated that anxious patients exhibit deficits in fear extinction. For example, individuals with panic disorder exhibit larger skin conductance responses during extinction training and rate the extinguished conditioned stimulus as more unpleasant, despite showing no differences from healthy comparison subjects in conditioned responses or valence ratings during or following conditioning (

50). Enhanced resistance to extinction has also consistently been reported in the PTSD population, as indexed by larger skin conductance responses to the conditioned stimulus (

51), larger heart rate responses (

52), and stronger online valence and expectancy ratings (

53) relative to trauma-exposed or healthy comparison groups. We have reported (

54,

55) that individuals with PTSD exhibit deficits in extinction recall, despite there being no differences in conditioning or within-session extinction training, as indexed by enhanced skin conductance responses during recall but not during conditioning or extinction training. We have also reported (

55) a negative correlation between symptom severity in PTSD and extinction recall. One recent study (

56) reported enhanced conditioning combined with impairments in fear extinction in PTSD compared with trauma-exposed comparison subjects and a positive correlation between symptom severity and both the enhanced conditioning and the impaired extinction. PTSD impairment in fear inhibition has also been reported using a model of inhibition that isolates the inhibitory component of extinction (

57), and this effect was not observed in a cohort of depressed people (

58).

Evidence From Neuroimaging Studies Using Fear Extinction

The data discussed above indicate that anxiety disorders are associated with deficiencies in the neural circuitry of extinction. However, these deficiencies have not been thoroughly examined in the context of fear inhibition. Indeed, only a few studies have investigated neural activity during fear extinction in anxious patients. The first to do so using positron emission tomography (PET) (

59) demonstrated that in individuals with PTSD compared with healthy comparison subjects, fear acquisition is associated with increased resting metabolic activity in the left amygdala, and fear extinction is associated with decreased resting metabolic activity in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (

59). We extended these results using fMRI to examine extinction recall the day after extinction training (

55). We found that PTSD patients exhibited reduced activity in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and the hippocampus but heightened activity in the dorsal anterior cingulate during extinction recall. We also observed a positive correlation between the magnitude of extinction recall and activity in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and hippocampus across all participants. These results suggest that hyperactivity in the dorsal anterior cingulate and hypoactivity in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex may contribute to the impairment of extinction observed in PTSD. A subsequent study from our group (

60) demonstrated that during extinction recall, PTSD patients showed both reduced ventromedial prefrontal cortex activity and heightened dorsal anterior cingulate activity in response to the extinction context, suggesting that hyperactivity in the dorsal anterior cingulate and hypoactivity in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex may also mediate an inability to use contextual cues to predict safety (

Figure 1). The function of the neural circuitry of extinction recall across the different anxiety disorders beyond PTSD remains to be examined, although the studies described suggest that investigating neural activity during fear extinction tasks may be a useful means of understanding the psychopathology underlying anxiety disorders.

Can the Extinction Model Be Used to Predict Vulnerability to Anxiety Disorders?

To date, there are very few published studies in this domain to answer this question. One study (

61) reported that genetic heritability accounted for 35%–45% of the variance associated with conditioning and extinction rates. Consistent with that finding, another study (

62) assessed the potential use of the extinction model to predict vulnerability to anxiety disorders. The study examined the extinction of skin conductance responses and corrugator muscle electromyogram (EMG) responses to an aversively conditioned stimulus (colored circles) in firefighters during cadet training. Participants were reassessed for PTSD symptoms within 24 months after training, by which time all had been exposed to a work-related trauma. Reduced extinction of EMG responses during extinction training at the time of cadet training accounted for 31% of the variance associated with subsequent PTSD symptoms 24 months later. Thus, these initial studies support the premise that impaired extinction may be a precursor to anxiety and that early detection of this impairment may be used to predict vulnerability to anxiety. Nonetheless, in a small sample of monozygotic twins, we reported impaired extinction retention in participants with PTSD, which was not present in their co-twins (

54), suggesting the lack of any preexisting presence of impaired extinction retention in participants with PTSD. One possible explanation for this discrepancy is that the sample size may have been too small. Another is that extinction retention deficits may be acquired, whereas the ability to learn to fear and extinguish fear within a session may be associated with genetic predisposition to developing PTSD. Animal studies appear to support distinct mechanisms for extinction learning and extinction recall, and recent imaging studies in twins suggest that while some of the psychopathology of PTSD appears to precede trauma exposure, other neural deficiencies appear to be acquired (see below).

No studies have investigated whether alterations in the functional activity of the neural circuitry involved in extinction can predict subsequent development of PTSD. However, studies that have investigated differences in brain morphology using structural MRI have consistently demonstrated that PTSD is associated with decreased hippocampal volume (

7), although it remains controversial whether or not alterations in brain morphology are a precursor to or a consequence of PTSD. At least one study supports the notion that a smaller hippocampal volume is predictive of PTSD development (

63). The study demonstrated that monozygotic twins discordant for trauma exposure in whom the trauma-exposed twin developed PTSD had smaller hippocampal volumes than monozygotic twins discordant for trauma exposure in whom the trauma-exposed twin did not develop PTSD. Furthermore, symptom severity in the participants with PTSD was negatively correlated with their own hippocampal volume as well as that of their co-twin. On the other hand, a later study using the same participants (

64) found reduced gray matter density in the anterior cingulate of those with PTSD relative to their combat-unexposed co-twins, as well as to combat-exposed twins without PTSD and their co-twins, suggesting that neural abnormalities in this region may be a consequence of PTSD. A more recent study (

65) examined resting state activity using PET in dizygotic twin pairs in which one co-twin had PTSD compared with twin pairs in which one co-twin had been exposed to trauma but did not develop PTSD. The study reported a higher resting state in the dorsal anterior cingulate and midcingulate cortex in participants with PTSD and their co-twins relative to trauma-exposed participants and their co-twins, suggesting that alterations in the neural circuitry underlying conditioning may be a risk factor for subsequent development of PTSD. Clearly, more work is needed to elucidate the extent to which preexisting dysfunctions in extinction ability and the neural circuitry underlying extinction contribute to subsequent development of PTSD and other anxiety disorders.

Can the Extinction Model Be Used to Predict Treatment Response?

As noted previously, even the most successful treatments for anxiety disorders are associated to some extent with relapse, and some patients fail to respond at all. At this point, the factors that predict responsiveness to treatment remain largely elusive. One possibility is that the extinction model may be employed to predict the likelihood of responding to CBT-based treatments that primarily use extinction procedures. To our knowledge, no studies have investigated extinction ability prior to treatment and correlated the magnitude of extinction retention with the success of treatment response. However, two studies have examined neural activity in the circuitry mediating extinction prior to treatment. One examined resting metabolic activity in participants with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) before they received behavioral therapy or fluoxetine treatment (

66). In the behavioral therapy group, positive treatment response was correlated with higher pretreatment metabolism in the left frontal orbital cortex, while the reverse was the case for positive response to the medication treatment (that is, treatment response was negatively correlated with pretreatment left frontal orbital cortex metabolism). The second study examined the pattern of neural activation in response to fearful and neutral faces in individuals with PTSD prior to CBT (

67). They found that poor treatment response, as measured 6 months after treatment, was associated with greater activation in the amygdala and the ventral anterior cingulate region. Although these findings are preliminary, they suggest that pretreatment measurement of neural activity in the extinction circuitry could provide important information regarding the intensity, duration, and type of therapy required to prevent or reduce subsequent relapse.

Can the Extinction Model Be Used to Improve Current Treatments or to Test Novel Treatments?

As exposure therapy is based on extinction, laboratory investigations of the neurobiology of extinction in the rodent and the human have proved fruitful in providing ways of enhancing CBT for anxiety disorders. Without a doubt, the most successful of these investigations has been that of the effect of

d-cycloserine on the extinction of conditioned fear, which was initially demonstrated to enhance extinction of conditioned fear in rats and to reduce stress-precipitated relapse (

68,

69). Since then,

d-cycloserine has been shown to enhance exposure therapy in humans with a range of anxiety disorders (

70). Investigations of

d-cycloserine and extinction have influenced a new wave of thinking in pharmacotherapy for anxiety disorders. Rather than developing drugs that merely mask the symptoms of anxiety (and often interfere with the effectiveness of psychological therapies), researchers are investigating the potential of drugs that can be used to augment the underlying therapeutic mechanisms of CBT. Numerous novel pharmacological enhancers of extinction are currently being investigated in preclinical and clinical research (

71).

Other studies have focused on directly stimulating the neural structures that have been proposed to be dysfunctional in anxiety. In repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), cortical neurons are stimulated noninvasively and without the side effects often associated with ECT. In one study (

72), rTMS of the lateral prefrontal cortex was shown to reduce compulsive urges in people with OCD as measured 8 hours after stimulation, an effect that was not found when the midoccipital region was stimulated. Another study (

73) reported that 10 sessions of high-frequency stimulation to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex significantly reduced PTSD symptoms up to 3 months after treatment (

73). These findings suggest that mere stimulation of neural regions underlying extinction can be therapeutic.

Results from rTMS studies raise the possibility that extinction procedures may be combined with brain stimulation to enhance the effectiveness of such treatments. Indeed, this has already been investigated at a preclinical level in rodents. One study (

74) found that combining conditioned stimulus presentations with infralimbic stimulation reduced conditioned freezing during extinction training in rats. Furthermore, this reduction in freezing remained evident during extinction recall, an effect that was absent when the stimulation was not paired with the conditioned stimulus presentation. As rTMS is already being examined in clinical trials, the potential exists for translating this finding from the rodent to clinical populations. Notably, the recent advances made in enhancing current treatments for anxiety reviewed here all stemmed from preclinical investigations of extinction in nonhuman animals, thus illustrating the validity of extinction as a model of treatment.

Caveats About the Fear Extinction Model

Several limitations of the fear extinction model and its proposed underlying neural circuitry have been noted. For example, it was recently reported (

75) that PTSD was less prevalent in Vietnam War veterans who had experienced damage to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex or the amygdala, a finding that appears contradictory to the model suggesting that anxiety results from a failure of prefrontal inhibition over amygdala activity. However, the average lesion area in that study was not limited to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex; large portions of the surrounding anterior, lateral, and dorsal prefrontal cortices were included. Future studies with focal lesions that are more confined to the ventromedial region should specifically examine the relationship between ventromedial lesions and PTSD prevalence.

Another limitation to the extinction model is that neuroimaging studies of anxiety have not always produced results that are consistent with the current neural model of fear extinction. For example, some studies have reported no difference in amygdala activation during the presentation of trauma-related reminders in PTSD patients (

76,

77). In addition, some studies have reported hyperactivation in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex during symptom provocation in PTSD patients compared with healthy (

78) and trauma-exposed (

79) comparison subjects, or no difference in ventromedial prefrontal activation between groups (

80). These inconsistencies are concerning, and the underlying reason for them is unclear, but they may stem from the fact that symptom provocation and fear extinction tasks measure slightly different functions (fear processing as opposed to fear inhibition).

Finally, it is clear that the extinction model does not capture all aspects of clinical anxiety, particularly cognitive components such as anticipatory anxiety (

9). Similarly, it does not capture all aspects of any given anxiety disorder. For example, the underlying pathogenesis of OCD, which is characterized by intrusive thoughts and rituals, is not well modeled by extinction and may be regulated by an entirely different neural circuit from that of extinction (

9). Furthermore, while extinction is a dominant component of CBT for anxiety disorders, it is not the only mechanism of therapeutic change. For example, CBT also involves exposure to the feared outcome itself, an aspect that is perhaps better modeled by habituation paradigms (

81). Nevertheless, despite these limitations, the data reviewed here indicate that the fear extinction model can be used to understand the psychopathology of anxiety disorders and to determine similarities and differences among the various diagnostic categories.

Future Directions

In this review, we have presented four arguments. First, the extinction model is advantageous because it models the commonly accepted underlying dysfunction in anxiety disorders (CBT); because it models the most widely used treatment of anxiety disorders; and because there is much evidence for the cross-species validity of the model. Second, a basic neural circuitry that regulates fear extinction has been identified in rodent and human research, and there is moderate evidence to suggest that this neural network is dysfunctional in anxiety disorders. Third, there is preliminary evidence to suggest that the extinction model may potentially be used to detect vulnerability to anxiety disorders and to predict the likelihood of treatment response. Fourth, there is considerable evidence to suggest that the extinction model can be used as a means to investigate ways of enhancing existing treatments for anxiety. We argue that these factors make the extinction model—and its underlying neural circuitry—an excellent candidate for a biomarker of anxiety disorders, as well as a useful tool for understanding the psychopathology of anxiety. However, there is further work to be done to help validate the extinction model as a biomarker of anxiety disorders across diagnostic categories and to ensure that the model continues to lead to developments in treatment. Below, we summarize what we believe to be the most important future directions.

The Neural Circuitry Underlying Fear Extinction Retention Across Diagnostic Categories

In order to use the extinction model as a biomarker for anxiety disorders across the board, it is clear that more research must be conducted to clarify whether or not similar dysfunctions exist in the neural circuitry of extinction in populations with anxiety disorders other than PTSD, as measured with imaging techniques during laboratory extinction tasks. To foster comparisons across these studies, it will be important for future research to employ a standardized extinction paradigm. Earlier studies of fear extinction examined fear conditioning and extinction acquisition in a 1-day paradigm and did not examine subsequent extinction retention (

24,

53,

59). We argue that later studies that examined extinction retention in a 2-day paradigm may be more clinically relevant (and may be more sensitive to detecting behavioral and neural differences between clinical and healthy populations), given that the impairment in fear extinction in anxious populations may be specific to the retention of extinction memories over time rather than in the acquisition of such memories. This thesis is supported by recent studies that have reported no differences in fear conditioning or extinction acquisition but significant differences in extinction retention in clinical populations (

54,

55) and by findings that anxious populations tend to show recovery of extinguished fear over time.

Focus on Less Studied Factors and Populations

Focusing research on anxiety disorders dimensionally rather than on the specific diagnostic categories may also open up the possibility of examining historically understudied factors and populations that may be critical to furthering advancements in treatment. For example, very little research has examined the role of sex hormones on fear extinction or sex differences in extinction, despite the fact that women are twice as likely as men to develop anxiety (

1). Indeed, sex differences in emotional memories have consistently been documented in rodents and humans (

82). Furthermore, stress differentially affects fear acquisition in male and female rodents, and this effect appears to be modulated by estradiol (

83). In addition, damage to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex differentially affects men and women, with unilateral right damage producing severe defects in men while unilateral left damage produces severe defects in women (

84). Emerging evidence in both rodents and naturally cycling women suggests that fluctuations in the menstrual cycle alter extinction retention (

85,

86) and, furthermore, that exogenous estradiol administration may be a novel enhancer of extinction retention (

85,

87). These recent findings strongly suggest that future research should examine the effect of hormones on fear extinction, or at least consider sex as an important variable.

Another relatively neglected factor is the effect of sleep on extinction. Rodent research has demonstrated that fear conditioning reduces REM sleep, whereas fear extinction restores normal levels of REM sleep (

88), except when extinction recall is disrupted (

89). In healthy humans, sleep enhances extinction recall (

90). Furthermore, sleep disturbance is associated with poor treatment outcome in PTSD, and activity in the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex modulates sleep (

91). However, the relationship between sleep and extinction is not well defined, particularly in human clinical samples. Investigation into the effect of sleep on extinction may lead to new insights into methods of augmenting exposure therapy by modulating sleep.

Using a dimensional diagnostic system to recruit research samples may also make it easier to examine fear extinction in special populations, such as children, adolescents, and the elderly. Preclinical research has revealed that developing rats exhibit relapse-resistant extinction that depends on different molecular and neural circuitry from those that mediate extinction in adult rats (

92). Extinction also appears to be altered during adolescence in rats, a time when the prefrontal cortex undergoes rapid reorganization, and is associated with high rates of relapse and altered molecular activity within the infralimbic cortex (

93,

94). Studies that examine extinction across development may identify the specific point during development at which the dysfunction in neural circuitry emerges (which may be several years prior to overt symptom onset). For example, it has been shown that temperament measured at 4 months of age is predictive of orbital and ventromedial prefrontal structure at 18 years of age (

95). This kind of longitudinal research may lead to insight into how to protect against the development of anxiety.

Conclusion

The advent and continuous development of neuroimaging tools have allowed us to form a solid base of knowledge about the neural dysfunctions across anxiety disorders. The recent explosion of interest in understanding the neural substrates of fear extinction in rodents reflects the importance of the neurobiology of fear inhibition and its relevance to anxiety disorders. Research using healthy human subjects has confirmed the cross-species validity of this model and has demonstrated that the behavioral and neural mechanisms underlying fear extinction have been strongly preserved across evolution. Our current knowledge base from these two fields should allow us to move forward and merge the two together using a multimodal across-species approach. While this experimental model is not perfect, as it does not capture all aspects of any given anxiety disorder, we argue that it is a good model for understanding the neural circuits underlying learning not to fear per se, which can then be directly translated to understanding anxiety disorders and improving treatment outcomes for patients.