Review of Prospective High-Risk Studies

Laroche et al. (

23,

28) published findings from a 3- to 7-year prospective follow-up study reporting on 37 offspring from 21 families with a bipolar parent selected from an outpatient clinic; there were no control families for comparison. The bipolar parent had to have been maintained on lithium for at least 1 year and have children between 5 and 18 years old. At the time of last assessment, the mean age of offspring was 16.2 years (range=8–25 years). DSM diagnoses were made in 24% of the offspring (N=9/37) and clustered in the affective/internalizing domain. While no cases of full-threshold ADHD were diagnosed, the study reported significantly higher scores in hyperactive, anxiety, neurotic, and depression symptoms in the high-risk offspring who had a DSM diagnosis (mostly mood and anxiety disorders) compared with those who did not. These findings suggest that early in the course of evolving bipolar disorder, anxiety and minor depressive disorders dominate and that inattention symptoms may occur in the context of the evolving mood disorder.

Radke-Yarrow et al. (

21) reported on a community cohort of children of affectively ill and well mothers after 3 years of prospective follow-up. Two siblings from 100 families were included, one in infancy (1.5–3.5 years old) and the other in early childhood (5–8 years old). An association between disruptive behavior disorders and families under higher stress (χ

2=7.05, p<0.01) and from lower socioeconomic status (χ

2=7.46, p<0.02) was reported. Children of affectively ill mothers were more likely to manifest problems with depression symptoms in middle (χ

2=18.69, p<0.0001) and in later childhood (χ

2=10.77, p<0.0001). Anxiety disorders were identified in infancy and early childhood in offspring of both healthy and depressed mothers, whereas anxiety did not become frequent until later childhood in offspring of bipolar mothers. In summary, it became evident that children of depressed mothers were the most severely affected with psychiatric problems across internalizing and externalizing domains from preschool through early and later childhood. Children of bipolar mothers held an intermediate position, with psychiatric and behavioral problems becoming evident in middle and later childhood. A gender effect, with boys showing more disruptive problems and girls more internalizing problems, was also reported.

In subsequent years, this cohort was followed up in adolescence (11–19 years old) and again in young adulthood (18–28 years old), with some families joining the study, some changing category, and others leaving the study. Main findings reported by Meyer et al. (

29) included that 19% (N=6/32) of the offspring of bipolar mothers and 7% (N=3/42) of the offspring from unipolar mothers developed bipolar disorder at a mean age of 16.6 years. Based on rating scales, the study found a higher rate of childhood attention and behavioral symptoms in the offspring who developed bipolar disorder relative to those with no mood disorder in adulthood. The authors also reported that specific deficits in executive functioning during adolescence (as evidenced by certain parameters on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test) and premorbid attention problems preceded the formal diagnosis and treatment of bipolar disorder. All offspring with both childhood attention problems and executive functioning deficits in adolescence were diagnosed with bipolar disorder. These findings are limited by the small number of cases of bipolar disorder and by the degree of assortative mating in the families. Nonetheless, they are consistent with the interpretation that in at least some high-risk children, cognitive antecedents, but not a clinical diagnosis of ADHD, are associated with a subsequent risk of developing bipolar disorder.

In a prospective study of school-age children (8–16 years old) of mothers with bipolar disorder, depression, chronic medical illness, or mothers who were healthy, Hammen et al. (

22,

30) reported on psychopathology and psychosocial problems (based on the Child Behavior Checklist completed by the mother and a teacher) at baseline and at 6-month intervals until age 3 years. ADHD was diagnosed in 6% of offspring of bipolar mothers compared with 9% of offspring of depressed mothers and 5% of offspring of healthy comparison mothers. A substantial proportion of the psychopathology of the offspring of bipolar mothers was milder than that of the offspring of depressed mothers, with anxiety disorders being prominent. Based on maternal and teacher reports, there was no difference in social competence, school behavior scores, or academic performance ratings between the children of bipolar mothers and the children of healthy mothers (

30). While limited by the relatively small number of children followed for up to 3 years, the findings are consistent with the interpretation that ADHD is not overly represented among the offspring of bipolar mothers and that the early psychosocial and school functioning of these high-risk offspring is generally comparable to that of the healthy population and different from that of children of depressed mothers.

Akiskal et al. (

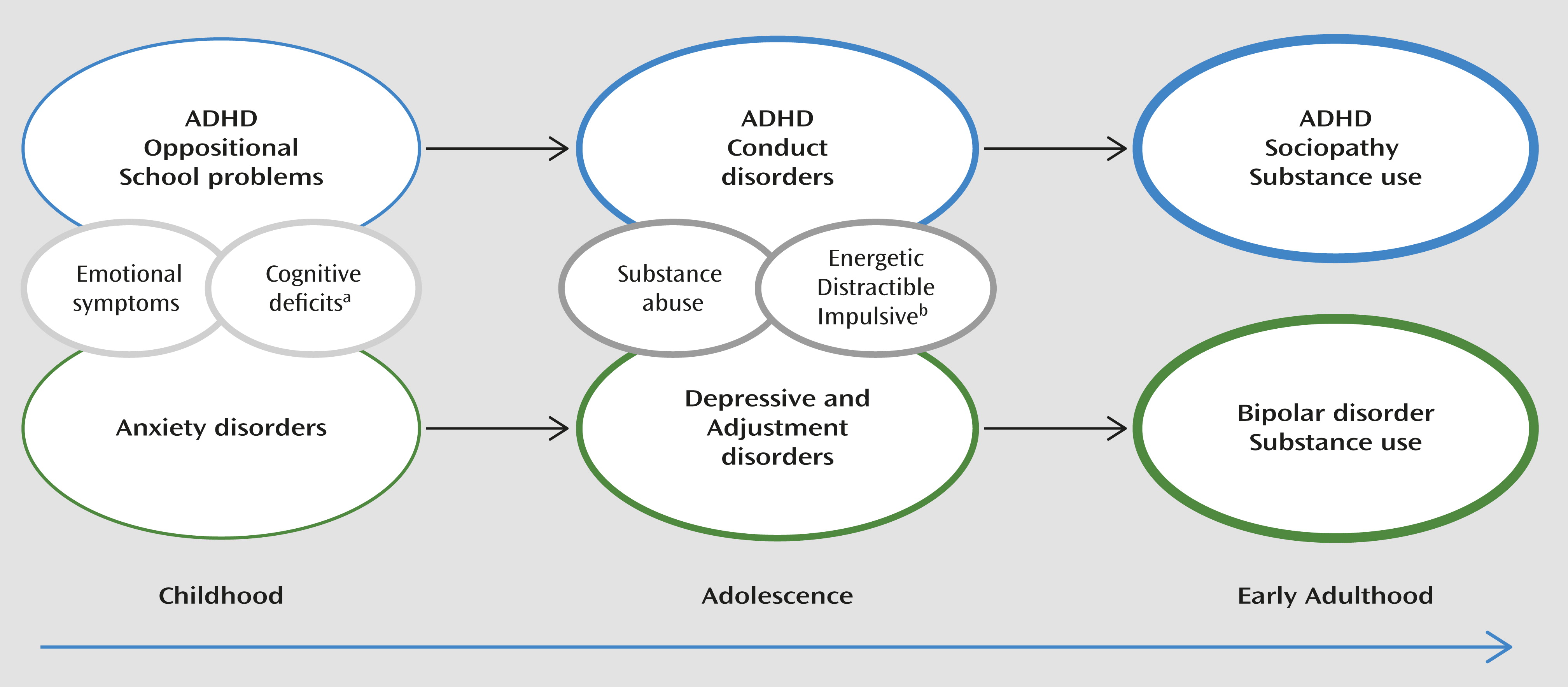

24) charted the prospective course of evolving psychopathology in 68 referred (symptomatic) juvenile relatives (offspring and siblings) of adult patients with confirmed bipolar disorder who were assessed and treated in a specialty mood disorders outpatient clinic. At baseline, 44 of the 68 high-risk youths had been previously seen by child mental health professionals, and 16 had been diagnosed with emotional problems related to family or peers, eight with neurotic (anxiety) disorders, seven with conduct disorder, seven with schizophrenia, and four with ADHD. Interestingly, none of the offspring assessed in childhood were thought to have a primary mood disorder. Within the first year of prospective study, 24 youths were diagnosed with major depression, 11 with manic or mixed episodes, and 22 with subaffective disorders. After an average of 3 years of prospective study, recurrences occurred in those with major affective disorders as well as conversion from subaffective to major affective and from unipolar to bipolar spectrum. In summary, nonaffective childhood diagnoses preceded the onset of minor and major mood disorders. Depressive and subaffective disorders predominated early in the course, while full-blown hypomanic and manic episodes were not seen until after age 13. Finally, similar to the findings of Laroche et al. (

28), childhood antecedents of “hyperactivity” and “antisocial” symptoms were described as “phasic,” occurring alongside mood symptoms and not responsive to trials of stimulant medication.

Egeland et al. reported on a prospective study of school-age children of Amish parents affected with bipolar disorder (100 children) and healthy parents (110 children) who were systematically assessed at 7 years (

31) and 10 years (

27) after baseline. The study evolved from research involving the adult Amish bipolar disorder patients, who estimated that their illness manifested 9 to 12 years earlier than the age at onset of the full-blown diagnosis. The goal was to identify which childhood symptoms predicted the development of bipolar disorder in the children at genetic risk. All families were from the Amish community and comprised a high-risk group (one bipolar parent and one well parent), a comparison group with positive family history (one well sibling of the bipolar disorder proband and the other well parent), and a comparison group with negative family history (two well parents and no relatives with bipolar disorder). After 7 years of prospective follow-up, 38% of the offspring of bipolar parents were tagged as being at risk based on symptom profiles, compared with 17% of the offspring from comparison families (83% from the positive family history subgroup). The specific clinical risk features flagged in the children of bipolar parents included anxious/worried, attention poor/distractible in school, low energy, excited, hyper alert, mood changes/labile, school role impairment, sensitivity, somatic complaints, and stubborn/determined. There was also evidence of a phasic nature of the symptoms involving mood, energy, sleep, and temper problems.

At the 10-year follow-up, the mean age of the offspring groups was 17–18 years, and 41% of the offspring of bipolar parents were tagged as being at risk based on symptom profiles, compared with 16% of the offspring from comparison families (82% from the positive family history subgroup). The same core symptoms remained at higher frequency in the high-risk offspring except that low energy, anger, fearfulness, and sensitivity dropped below significance level, while high energy, sleep difficulties, excessive talking, loud talking, and problems with thinking and concentration reached significance. Taken together, these findings suggest that during development, putative prodromal features in high-risk offspring shifted from anxiety-depressive to more manic symptoms. Distractibility, stubbornness, and being easily upset were first noted early in childhood, alongside the affective symptoms, whereas “problem concentrating” was associated with manic-like symptom clusters later in development. The episodic nature of these symptom clusters continued throughout development. Furthermore, the authors confirmed that ADHD as a syndrome was “relatively absent.”

An ongoing prospective study of 140 children of bipolar parents in the Netherlands, reported by Wals et al. (

16,

26,

32), builds on the findings of the previously described studies. The majority of families (102 children; mean age=16.1 years) derived from a community-based Dutch Patient Association, while the others were identified through outpatient clinics. High-risk families had comparable socioeconomic status and higher IQs on average compared with those of the Dutch general population, and 76% of families were intact. While symptom rating scales were generally comparable between the high-risk group and the normative population, daughters of bipolar parents had higher scores on Child Behavior Checklist subscales for total problems, internalizing, externalizing, somatic complaints, anxious/depressed, social problems, delinquent behavior, and aggressive behavior. Sons of bipolar parents scored higher on Child Behavior Checklist subscales of total problems, externalizing, thought problems, and aggressive behavior. On self-report, high-risk older adolescent girls reported more attention problems, while teachers reported no differences in attention or behavior problems in the high-risk boys or girls compared with the normative population.

At last follow-up, covering almost 5 years, the cohort had 129 children, with a mean age of 20.8 years (

26). The risk of ADHD over the prospective waves of assessment remained stable, while the risk of mood disorder and bipolar disorder increased. The lifetime risk was 10% for bipolar disorder (I or II), 40% for any diagnosable mood disorder, and 5% for ADHD. In those high-risk offspring with bipolar disorder, the index mood diagnosis was almost always depressive in polarity, at a mean age of 13.4 years (SD=4.2), and the index hypomanic/manic episode manifested a mean of 4.9 years (SD=3.4) later (at 18.4 years old). Only one of these 13 bipolar subjects had treatment with stimulant medication before the development of the activated episode. Collectively, these findings lend further support to reports of a variety of emotional and behavioral childhood antecedents followed by subaffective and depressive disorders in early adolescence, and hypomanic/manic episodes later in life. ADHD, as a clinical diagnosis, was not higher in the high-risk offspring than in the general population based on either clinical interview assessment or teacher reports.

Finally, our group has published several reports from an ongoing longitudinal high-risk study (

33–

36). The high-risk families (one affected and one well parent) were selected through specialty clinical research programs and diagnosed based on best estimate procedure. Bipolar parents were divided on the basis of an unequivocal response or nonresponse to long-term lithium treatment. Lithium response identifies a more homogeneous subtype of classical bipolar disorder (

37), while lithium nonresponse is characterized by a chronic illness course and a higher familial risk of psychotic disorders (

38).

Early on, we reported an association in the high-risk offspring between subjective problems in attention and symptoms of depression that was not related to any obvious deficit in sustained attention on psychological testing (

39). In subsequent analyses, our group found comparable lifetime rates of clinically significant ADHD (often comorbid with learning disabilities) in high-risk (8.3%) and comparison offspring (5.8%) (

25). The current age-adjusted lifetime risk of major affective disorders in 231 high-risk offspring at a mean age of 25.7 years old (SD=9.23) is estimated at 52.8% (mean age at onset=16.8 years) and bipolar disorder at 13.5%. Interestingly, higher rates of ADHD and other neurodevelopmental abnormalities, including learning disabilities and cluster A traits, were observed in the subgroup of offspring of parents who did not respond to lithium (

35). Furthermore, a recent analysis (

40) found that this neurodevelopmental phenotype was more frequently observed in high-risk offspring who developed a substance use disorder compared with those who did not (18.0% compared with 9.3%, p=0.06). While limited by a small sample, across this high-risk cohort, ADHD does not appear to be a robust predictor of major affective disorder or bipolar disorder. Of those high-risk offspring with a childhood diagnosis of ADHD, 28% have so far gone on to develop a major affective disorder (major depression or bipolar I or II) and 11% a minor affective disorder (dysthymia or depression not otherwise specified), while 93% of the high-risk offspring with a major affective diagnosis did not have antecedent ADHD.