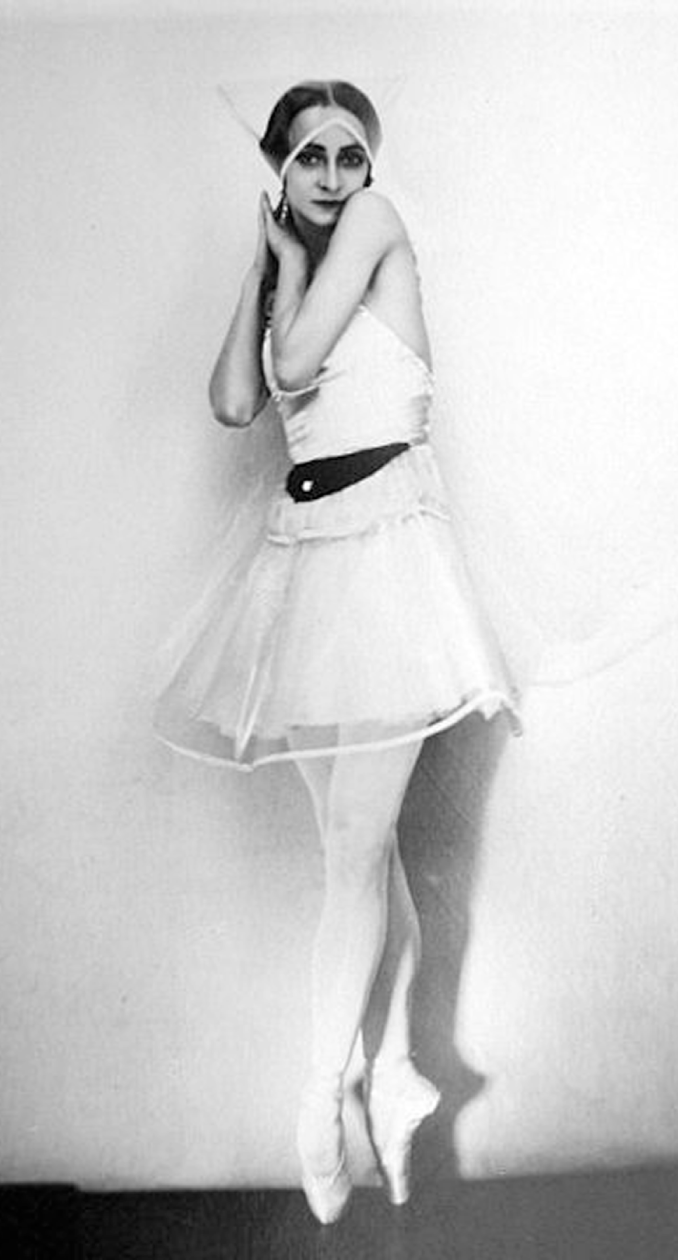

Olga Spessivtseva is one of the most famous ballerinas to develop a psychotic disorder. Born in 1895 in a small Russian village, she was sent to an orphanage in St. Petersburg after her father's death in 1901. A shy, withdrawn child, Spessivtseva began her dancing career at St. Petersburg's Imperial Ballet Academy at the age of 10. She soon became one of the most admired dancers in the company and, after joining the Mariinsky Theater, was promoted to soloist in 1916 and ballerina in 1918 (

1). After the brutal beginning of the communist revolution, she faced significant problems maintaining her artistic integrity as she was forced to perform in front of the leaders of the revolutionary party. During the atrocities of the “Red Terror,” Spessivtseva was asked to cut the ribbon to officially open the first municipal crematorium in St. Petersburg and was forced to select a body in the city morgue for a test cremation. It has been reported that she wept at the horror of carrying out the task (

2).

After such traumatic experiences, Spessivtseva finally managed, in 1924, to leave Russia for Paris, where she became an acclaimed

étoile with the Paris Opera until 1932 (

1). Because of her flawless dancing, she was asked to visit several theaters all over the world (United States, Argentina, Europe, Australia), and most considered her to be “the supreme classical ballerina of the century” (

3). Her most famous role was that of the lead character in

Giselle; every dancer who has filled this role since that time has patterned her performance either directly or indirectly on that of Spessivtseva (

3). To prepare for the “Mad Scene” in Act 1, she visited several insane asylums to study the patients' gestures and gait.

Spessivtseva was renowned for her incorporeal lightness and virtuosity, and all the roles she performed during her career mirrored her personality traits, which were marked by subtle and fragile beauty, shyness, inwardness, and depressive tendencies. Her dancing performance was threatened by her fanatical perfectionism (

4). In 1934, she experienced her first mental breakdown, during which she wrote frantic letters to her mother complaining that her feet and legs were becoming paralyzed, possibly reporting kinesthetic hallucinations (

5). Additionally, she developed a complex persecutory delusion, believing that some ballet company members were spies who were trying to poison her or amputate her feet. Her friends' reports also portrayed a kind of dissociative episode (

4,

5). Her grace and fine classical technique vanished as her pliés, tendus, and other battements became ritualistic and distorted. During her last performance on the stage in 1934, she had a complete psychotic breakdown that began with random movements; eventually she became unaware of the music and the choreography, and the curtain was lowered. To justify the cancellation of the show, the newspapers reported that Spessivtseva had sprained her ankle.

Spessivtseva gave her last performance in 1939 and in the same year moved to New York because her patron considered the United States safer with the approach of the war (

1,

3–

5). In 1943, her delusions returned; she hid in a darkened hotel room, refusing even to recognize her close friends, crying that the spies were back, were outside the door, and would poison and kill her (

6). Her beloved friends Sir Anton Dolan and Dale Fern intervened, and Spessivtseva was admitted to the gothic Hudson River Asylum for the Insane, where she lived for the next 20 years. Thanks to her friends' constant care, as well as significant advances in psychiatric care, Spessivtseva was discharged from the hospital in 1963. She then moved to the Tolstoy Foundation Farm in Rockland County, N.Y., a rest home for the Russian community founded by Alexandra Tolstoy, the daughter of the novelist Lev (

1,

3–

5). She spent the rest of her life there, dying at age 96.

It could be argued that Spessivtseva may have suffered from a complex posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) with dissociative tendencies. Reactions to traumatic events in her early life may have determined a wide range of symptom clusters in addition to classic PTSD. Even if a diagnosis of schizophrenia is in keeping with the presence of persecutory delusions and hallucinations, the traumatogenic hypothesis of a psychotic breakdown cannot be ruled out.

Acknowledgments

Photograph taken from Wikimedia Commons.