Schizophrenia is one of the most important brain diseases that psychiatrists treat (

1). Studies comparing brain volume measurements in patients at the time of illness onset with healthy volunteers have indicated that the patients have smaller mean volumes in many regions, particularly the frontal lobes, suggesting that an aberrant neurodevelopmental process contributes to illness onset (

2–

6). Furthermore, longitudinal studies have shown that the mean differences in brain volumes continue to progress over time (

7–

12). Our own program, the Iowa Longitudinal Study (ILS), is the largest study of this type and has had the most frequent MRI assessments and the longest duration. We recently reported that ILS patients have greater tissue loss over time than healthy comparison subjects (which we refer to as “progressive brain change”) and that such change has functional significance, in that it is related to severity of psychotic symptoms and cognitive impairments (

12). The focus of scientific attention is now on determining why the tissue loss occurs and why it continues to progress.

The explanation is almost certainly multifactorial, implicating a range of genetic and environmental influences. Because initial clinical presentation (or onset) typically occurs during the teens and twenties, the current thinking is that the brain tissue loss may be due to aberrations in the neurodevelopmental processes that sculpt the brain into maturity during this period, such as gray matter pruning and increased myelination (

13–

17). But given that tissue loss continues after onset, it is likely that other factors may influence the loss as well. One explanation that is often advanced is that relapses occurring after initial onset may have a “toxic” effect on the brain (

9,

18–

21). This explanation is often used to argue for the importance of careful management of treatment and thoughtful choice of medications with a view to enhancing adherence (

22).

Despite the clinical importance of avoiding recurrent relapses, little research has been done to determine whether the number or duration of relapses is actually associated with brain tissue loss. To our knowledge, no study has examined the relationship between relapse and brain tissue loss using quantitative structural MRI brain measures in a repeated-measures longitudinal design. Hence, we examined this issue in the cohort of 202 patients in whom we previously documented the occurrence of progressive brain change (

12). These patients were recruited after their initial presentation for a schizophrenia spectrum disorder and were followed at regular intervals with repeated structural MRI scans for as long as 18 years.

One crucial component of such a study is establishing a clinically meaningful definition of relapse. Many definitions that have been used in the past have recognized flaws. Rehospitalization, once a solid indicator, no longer works well in the era of managed care and deinstitutionalization. An increase of 25% in symptom severity on a standard rating scale, also once commonly used, is flawed by its dependence on the severity of the baseline: if baseline is low to begin with, for example, a 25% increase would still be a low score on the overall scale, whereas a high baseline would produce a much larger increase in score; yet both instances would be classified as relapse and reflect very different levels of severity. A recent clinical trial led by Csernansky et al. (

22) therefore developed a definition of relapse that is now recognized as the optimal standard. It comprises six components: in addition to rehospitalization and rating scale changes, Csernansky et al. included other important indicators of relapse, such as deliberate self-injury, violent behavior, suicidal ideation, or a clinician’s judgment that the patient had become very much worse. This definition was initially developed and applied in a clinical trial that used Kaplan-Meier estimates of relapse risk as the primary outcome measure. Although it constitutes an important improvement for clinical trials, this definition may be less suitable for a study that examines the impact of relapse on brain tissue change, in that it only permits the investigator to estimate time to relapse or the number of relapses. It does not provide a way to measure how long the patient remained in a relapsed state. Yet, it is intuitively plausible that a prolonged period of relapse could have a stronger effect on brain tissue than a brief one. Consequently, a second goal of this study was to develop a definition of relapse that could measure duration of relapse and to compare it with the impact of number of relapses in relation to brain tissue loss.

Because relapse typically triggers an increase in treatment intensity (e.g., higher dosages of antipsychotic medication), it is also important to determine whether any observed brain volume changes are a medication effect rather than a disease effect. We and others have reported findings that intensity of treatment is itself associated with brain tissue loss, with support from both human studies and preclinical work in monkeys and rats (

23–

27). In one report (

23), we examined four predictors of brain tissue loss: duration of illness, illness severity, intensity of antipsychotic treatment (measured in dose-years), and substance abuse. Our analysis looked at each of these factors separately, controlling for the effects of the other three; we found illness duration and treatment intensity to be significantly predictive of tissue loss, while illness severity had a lesser effect and substance abuse had no effect. In that analysis, our measure of illness severity was relatively general: an average of the monthly scores on the Global Assessment Scale throughout the follow-up period. In the present study, we look at two more powerful indicators of illness severity: time spent in relapse and number of relapses.

Method

Patients and Assessments

We studied 202 patients drawn from the ILS. The ILS was initiated in 1987 and terminated in 2007, and it includes a total cohort of 542 first-episode patients who were recruited after their initial presentation for a schizophrenia spectrum disorder. Diagnosis at intake was based on the Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History, a structured interview developed for longitudinal research (

28). Patients were followed at 6-month intervals after intake, with assessment by a structured follow-up interview that documents clinical symptoms, psychosocial function, and treatment received across the entire timeline of surveillance. More intensive assessments (structural MRI and cognitive testing) were conducted at intake and at 2, 5, 9, 12, 15, and 18 years. For this relapse study, we selected a subsample of 202 patients who had at least two structural MRI scans and were followed for at least 5 years. About three-quarters were male (N=148). Over half (N=108) were antipsychotic naive at study entry. The patients’ mean age at first appearance of psychotic symptoms was 22.0 years (SD=5.9); at first antipsychotic medication, 24.5 years (SD=6.2); and at study intake, 25.8 years (SD=7.0). They had a mean of 12.9 years (SD=2.2) of education, and their parents had a mean of 13.4 years (SD=2.8).

Although few participants had scans at all six follow-up points, we nonetheless obtained a total of 659 scans, which we analyzed in this study. We obtained 146 scans at intake, four at 1 year, 144 at 2 years, 143 at 5 years, 100 at 9 years, 74 at 12 years, 35 at 15 years, and 13 at 18 years. The mean number of scans per patient was three, and the mean follow-up duration was 7 years. The decreasing number of scans over time reflects the fact that intake into the study occurred at a rate of 20–30 patients a year from the time of its inception, so that patients who entered the study later had shorter surveillance periods. Although all 202 patients had intake scans, we excluded 56 intake scans from the analysis because they were conducted during the first 2 years of the project with a low-field 0.5-T Picker scanner and did not produce data that were comparable to the 1.5-T data collected at intake for the remaining 146 subjects or any of the later follow-up data.

Relapse Definition

Our approach to defining relapse built on our previous work in developing a definition of remission from schizophrenia (

29). That definition, which has achieved wide acceptance in research studies since its publication in 2005, is based on the symptoms used to define the disorder in DSM-IV; remission is defined as symptom severity that is rated as mild or less for at least 6 months. For the present study, we developed a similar symptom-based definition of relapse. We defined relapse using a standard pair of rating scales, the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms and the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (

30,

31). A patient was considered to have experienced relapse if he or she developed a rating of moderately severe or very severe for at least 1 week for any of the positive symptoms or at least two of the negative symptoms. Conceptually, relapse must occur after a period of improvement, so we specified that this level of severity had to occur after a period when symptom severity was no greater than moderate. For comparison purposes, we also used the Csernansky criteria (

22) to identify the number of relapses experienced by each patient. The surveillance period consisted of the entire time each subject was in the study, which ranged from 5 to 18 years. Therefore, we have a comprehensive picture of the relationship between relapse and brain tissue change during the course of schizophrenia.

Structural MRI Data Acquisition

Apart from the early 0.5-T protocol (excluded from this analysis), we used two scanning protocols, which we refer to as MR5 and MR6 (

12). Both are multimodal (i.e., acquire T

2 and/or protein density [PD] sequences in addition to T

1), thereby providing optimal discrimination between gray matter, white matter, and CSF. For MR5 scanning, each participant’s data included T

1-, T

2-, and PD-weighted images collected on a 1.5-T GE Signa scanner. MR6 scanning was performed on a 1.5-T Siemens Avanto scanner using T

1 and T

2 sequences. Subjects continued in the same sequence throughout the study; those who began with an MR5 protocol remained in it for all scans, and those who began with an MR6 protocol remained in it as well. The two sequences differ primarily in slice thickness and in-plane resolution; both are acquired in the coronal plane. Voxel sizes for MR5 are 1.0×1.0×1.5 mm for T

1 scans and 1.0×1.0×3 mm for T

2 scans; voxel sizes for MR6 are 0.625×0.625×1.5 mm for T

1 scans and 0.625×0.625×1.8 mm for T

2 scans.

Image Analysis

The MR scans were analyzed using the BRAINS2 software program, a locally developed program that now yields automated quantitative measures of multiple brain regions and tissue types (

32–

38). Although BRAINS2 analysis was semiautomated for many years, we recently introduced advanced image processing algorithms that eliminate the need for manual intervention at the stages of image realignment, tissue sampling, and mask editing. In addition, inhomogeneity correction, intensity normalization, and mask cleaning routines have been added to improve the accuracy and consistency of the results. This fully automated image processing routine is known as AutoWorkup (

39). To eliminate any measurement artifacts that might occur as a result of rater drift over time and to reduce any that might be due to scanner upgrades, we recently reanalyzed all scans used in this study using this new AutoWorkup program.

Statistical Analysis

Relapse duration was defined as the sum of the duration of all relapse episodes that occurred between two consecutive MR assessments. The change in brain volume was defined as the difference between brain volumes in two consecutive MR assessments, normalized by intracranial volume. A repeated-measures linear model was used to model changes in brain volume; volume changes from the same subject are assumed to be correlated. The model was set up so that we could examine the effects of each of the covariates separately while adjusting for the effects of the others. Covariates considered in the model included time elapsed between two consecutive MR assessments, relapse duration, sex, age, MR type, and antipsychotic treatment intensity, as follows:

Change in volume between two consecutive MR assessments = β0 + β1 time elapsed between two MR assessments (interval) + β2 relapse duration within time period of MR assessments (interval) + β3 sex + β4 age + β5 MR type + β6 antipsychotic treatment intensity (dose-years) during interval + error.

Our primary variables of interest were the change in brain volume associated with relapse duration within each interscan interval (β2) and the change in brain volume associated with intensity of antipsychotic treatment as measured in dose-years (β6). β2 indicates the amount of tissue loss per year measured in cubic centimeters. β6 provides a measure of the amount of tissue lost per year in cubic centimeters for 1 dose-year of antipsychotic treatment; since most subjects received more than 1 dose-year of treatment, we report values calculated by multiplying the measure by a factor of 4, as this was the mean number of dose-years for the participants. Dose-years are calculated in haloperidol equivalents, so the values we report represent the amount of tissue loss associated with receiving 4 mg of haloperidol per day for 1 year. Our analysis of relapse number used the same regression equation but substituted number for duration as the β2. False discovery rate with the q value of 0.1 was used for multiple comparison correction.

Results

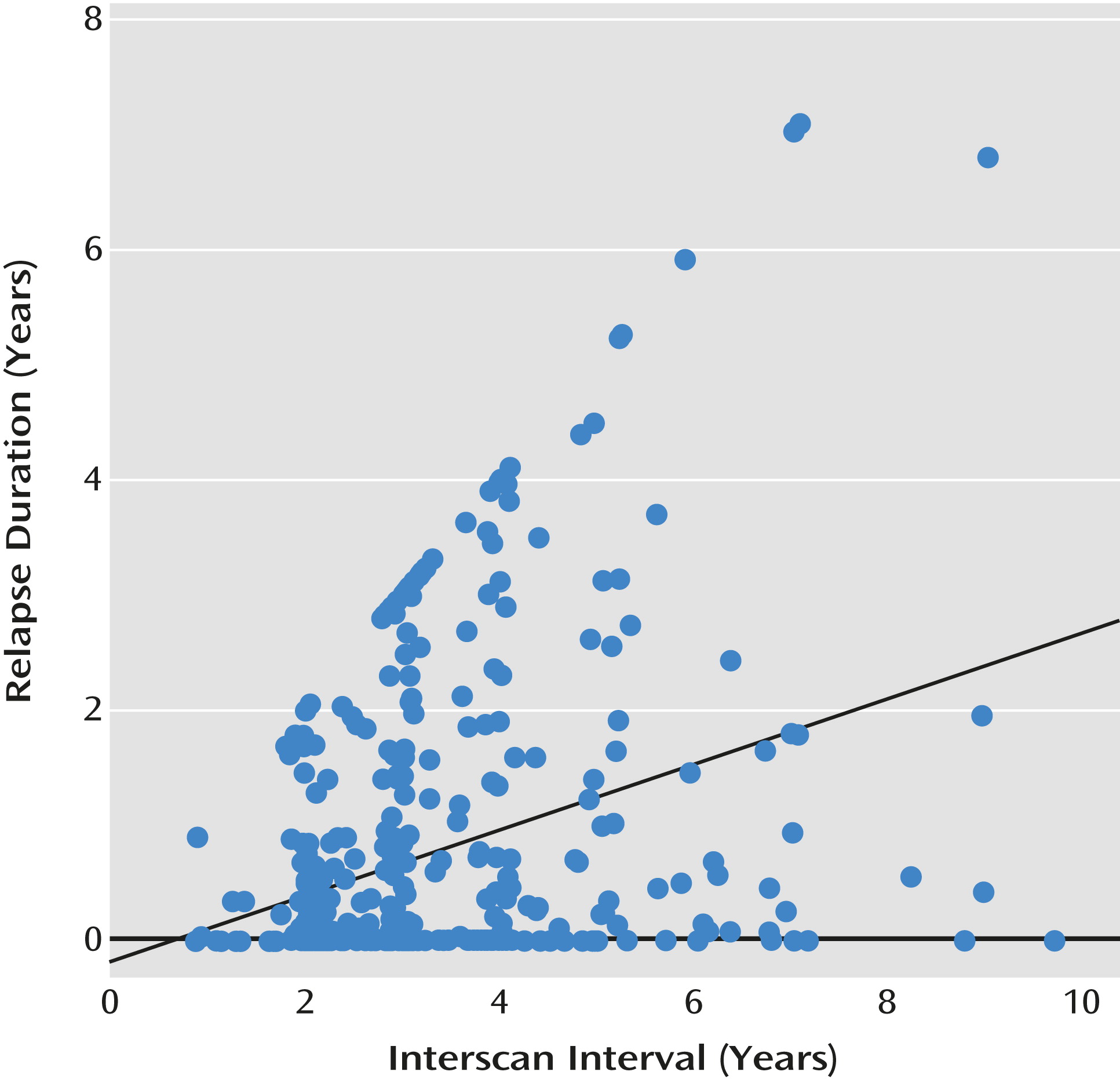

Of the 202 patients in our subsample, 157 experienced at least one relapse, 29 had no relapses, and 16 remained at a persistently severe illness level and did not improve enough that they could then relapse. For those who relapsed, the average number of relapses was 1.64, with a range of 1 to 4; the mean duration of relapse was 1.34 years (SD=1.40), and the maximum was 7.09 years. The pattern of relapse across the surveillance period is illustrated in

Figure 1, which plots duration of relapse against each of the interscan intervals (the interval between each of the multiple scans available for each of the patients). As the figure indicates, the early phases of the illness are characterized by multiple relapses of shorter duration. Over time, their number decreases, but a subset of patients experienced prolonged relapses.

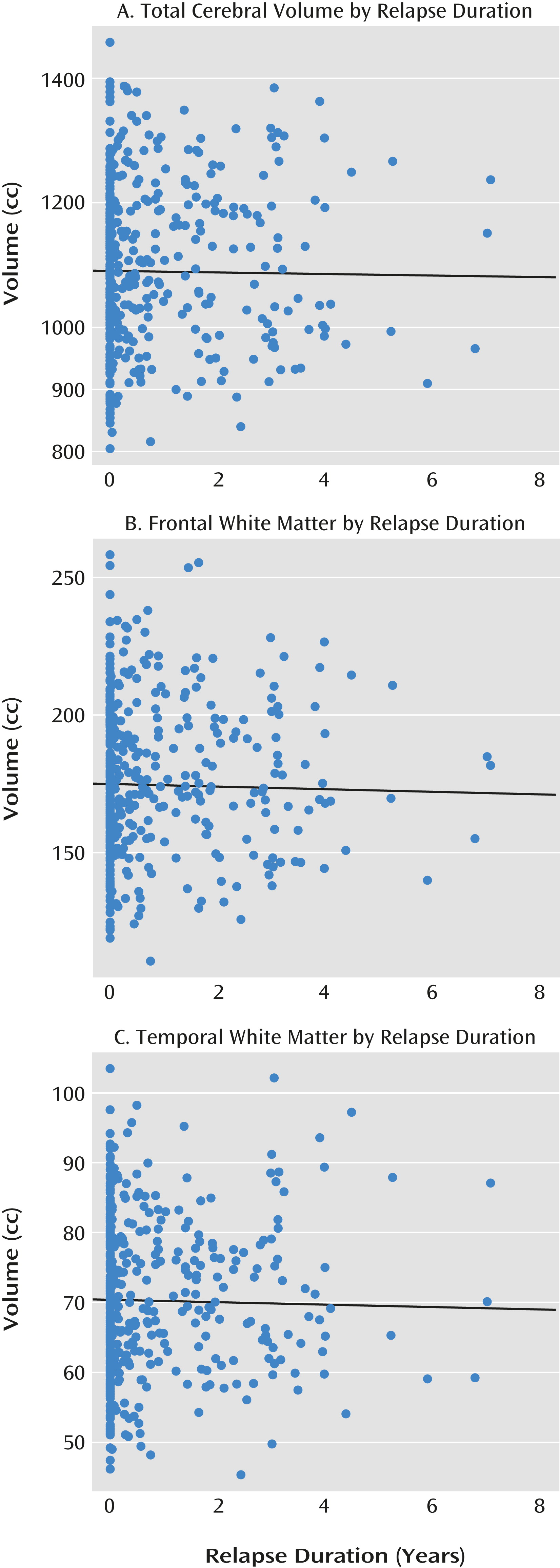

The relationship between relapse duration and change in volumes of brain tissue is summarized in

Table 1 and

Figure 2. Greater relapse duration is significantly associated with tissue loss in some brain regions. These include one general measure—decrease in total cerebral volume—as well as more specific measures; in particular, frontal lobe and white matter are more prominently affected. The effect of number of relapses is illustrated in

Table 2. No significant effects were observed, indicating that relapse duration is a more meaningful indicator of “disease neurotoxicity” than relapse number. Furthermore, the value of the beta coefficients is substantially smaller: a loss of 1.55 cc/year of cerebral tissue is associated with relapse duration, while the loss associated with relapse number is only 0.44 cc, and the loss in other brain regions is even smaller.

The effect of antipsychotic treatment intensity, after adjusting for other effects, is summarized in

Table 3. The analysis indicates that treatment intensity also has a relationship with brain volume changes. Statistically significant relationships include several generalized measures (total cerebral volume, ventricle:brain ratio, total temporal and frontal volumes, and parietal white matter volume).

Discussion

We examined two crucial factors that may influence disease progression in schizophrenia: the effects of relapse and the effects of treatment. Determining whether relapses have “neurotoxic” effects (and, by inference, whether relapse prevention may be neuroprotective) is one of the fundamental questions about mechanisms of disease progression that the field needs to address. We examined the relationship between duration and number of relapses and brain tissue loss in a large sample of patients, using a powerful within-subject longitudinal multiple regression design. In this design, we examined the duration and number of relapses during the interval between scans, using measures of relapse duration obtained before the measure of tissue change, thereby permitting us to infer a possible predictive relationship. We found that duration of relapse is closely related to loss of brain tissue over time in multiple brain regions, including indicators of generalized tissue loss (total cerebral volume), as well as loss in subregions, particularly the frontal lobes. Simply counting the number of relapses, on the other hand, has no predictive value.

Treatment with antipsychotic medication offers the best hope for relapse prevention, and yet some studies have suggested that greater intensity of antipsychotic treatment is associated with brain tissue loss (

23,

25,

26). We were able to address this issue by using a regression analysis that permitted us to simultaneously and independently evaluate the effects of relapse duration and antipsychotic treatment intensity on brain tissue measures. We found that both contribute to brain tissue loss but that they affect somewhat different brain regions. The treatment effects are more diffusely distributed, while the relapse effects are most strongly associated with frontal lobe tissue changes. In both cases, however, the effects are relatively small.

Given that the findings suggest that relapse has negative effects, combined with the reality that antipsychotic treatment provides the best hope for preventing relapse, how should one interpret these results? One aid to interpretation is to examine the size of the p values; they are roughly comparable for both relapse and medication effects, generally in the 0.03–0.01 range, although the relationship between relapse duration and total frontal volume is larger (0.0036). The interpretation must also take the nature of the beta coefficients into account, since they represent different things and are not directly comparable. The beta coefficients in

Table 1 represent tissue change in cc/year; for example, the total cerebral tissue loss associated with relapse duration is 1.55 cc/year, while the frontal lobe loss is 0.99 cc/year. The coefficients in

Table 3 represent the amount of tissue loss associated with treatment intensity; they are expressed as cc/4 dose-years in haloperidol equivalents, which was the average amount of treatment that these patients received. For example, total cerebral tissue is lost at a rate of 0.56 cc in patients receiving an average of 4 mg of haloperidol over 1 year. These calculations are based on a relatively long study period—5 to 18 years. Most patients receive medication for periods of that magnitude. It is noteworthy that the treatment effects observed in these patients are much smaller than those seen in animal studies, which are in the 10% range (

25–

27).

These findings have important clinical implications. Because they confirm previous work indicating that treatment intensity is associated with brain tissue loss, they suggest that clinicians should strive to use the lowest possible dosage to control symptoms. Because they also indicate that relapse is associated with brain tissue loss, they confirm the importance of relapse prevention. They provide empirical confirmation for clinical lore that has been widely accepted but has been lacking in scientific support. They suggest that relapse prevention after initial onset may convey a significant clinical benefit. This in turn suggests the importance of doing as much as possible to ensure treatment adherence as a way of preventing relapse, beginning aggressively at the time of illness onset. Adherence can be maximized in a variety of ways: maintaining good rapport and frequent supportive contact, choice of medications that have the lowest aversive side effects (such as akathisia and extrapyramidal side effects), and use of long-acting injectable medications.

This study has several limitations. Although we employed a sophisticated statistical design to tease apart complex relationships, they still cannot be completely disentangled. Although our regression model was set up to examine the relationship between relapse and tissue loss during each interscan interval, since we used measures of relapse obtained before the brain change to predict the amount of tissue loss during the interval, we cannot definitively infer that the effect is causal; we can only say that it is predictive. Although our regression analysis theoretically permitted us to examine relapse effects and treatment effects separately, relapse and treatment have other associated relationships that limit the interpretability of our results. For example, an alternative explanation may be that patients who have a more severe variant of the disease have more and longer relapses, perhaps by virtue of being less treatment responsive, and are also likely to have more brain tissue loss.

Another limitation is that treatment is naturalistic; a random assignment protocol would be preferable, but it would be impossible to implement over prolonged periods. We were not able to separate the effects of first- versus second-generation antipsychotics because nearly all patients had been treated with both during the long surveillance periods. Our clinical data summarizing relapse number and duration were collected at 6-month intervals and were available at all time points for all 202 subjects; however, the retrospective nature of the data is also a limitation. This limitation is somewhat mitigated by the fact that we based the assessments on all sources of information—patient self-report, interview with a family member, and records obtained from treating clinicians; we also conducted a study of the reliability and validity of retrospective evaluations that supports their accuracy (

40). Although the scan data are extensive, in an optimal design all patients would have scans at each specified time point; our examination of interscan interval data for each patient partially ameliorates this problem but does not resolve it completely. Some attrition occurred, which also limits interpretation; our 67% retention rate is, however, respectable for a study of such long duration, and we found no clinical differences between patients who remained in the study and those who dropped out.

In summary, these findings highlight the importance of identifying the mechanisms by which relapse may lead to brain tissue loss. A number of biological theories may explain this relationship. For example, a three-hit hypothesis has been proposed: early events result in dysplasia of key neural pathways, while later perionset events result in excessive elimination of synapses, causing altered glutamatergic and dopaminergic activity (

41). Relapse may perhaps lead to tissue loss via excitotoxicity by glutamatergic systems or oxidative stress mediated by dopaminergic systems (

42,

43). Teasing apart the mechanisms by which relapse may lead to brain tissue loss will require rigorous clinical trials, preferably with random assignment of medications that enhance treatment adherence (e.g., long-acting injectable agents versus treatment as usual) and that incorporate measures of relapse duration in combination with multiple imaging measures obtained at frequent intervals in first-episode patients over a feasible period, such as 1 year.