Mortality rates are higher in anorexia nervosa than in other psychiatric disorders (

1), but few studies have examined when death is more likely to occur in the course of this eating disorder. Most commonly, rates of premature death are described by the standardized mortality ratio, calculated as the number of observed deaths during a given period in a specific population of interest divided by the number of deaths expected in the general population, matched for age, race, and sex. A meta-analysis of 25 studies of patients with anorexia nervosa found a standardized mortality ratio of 5.9 in studies with a mean follow-up duration of 12.8 years (

1). A similar standardized mortality ratio of 6.2 over 13.4 years of follow-up has also been reported (

2). Although both are elevated, there was considerable variability in standardized mortality ratios across studies included in the meta-analysis (

1), and these standardized mortality ratios are lower than those reported in studies with shorter follow-up periods (

3,

4). Such variability across studies might be accounted for by ascertainment rates, sample size, severity of illness, and duration of follow-up, which may differ substantially from study to study. Thus, it would be instructive to examine the standardized mortality ratio in relation to the duration of follow-up as well as the duration of illness to understand whether there are high-risk periods for premature death in eating disorders.

Six longitudinal studies, including three in adolescents (

5–

7) and three in adults (

8–

10), have examined mortality rates over time. All of these investigations assessed anorexia nervosa patients at inpatient admission and again at multiple varying time points, ranging from 2 to 20 years after admission. Four of these studies found that the number of deaths increased with increasing duration of follow-up, with greater consistency in the adult studies than in the adolescent studies. However, it is unclear whether risk of death remained constant during follow-up because at least three studies (

5,

9,

10) detected a majority of recorded deaths earlier in the follow-up period.

In the literature, it remains unknown at what point in the progression of the disorder death is more likely to occur and whether there are differences between patients with anorexia nervosa who die relatively early in the follow-up period (or early in the course of the disorder) and those who die later (after a more protracted or chronic course). These two variables, timing of follow-up assessment and duration of illness, are distinct; individuals with eating disorders do not necessarily seek treatment or enter a study at the exact point when they meet full diagnostic criteria. To clarify this distinction, our first aim in this longitudinal study was to examine standardized mortality ratios at two time points as well as at varying years of duration of illness. Such data might be informative as to whether there is a peak period for death in eating disorders. Our second aim was to examine factors that might increase vulnerability to premature death. Studies have indicated that older age at hospital admission, longer duration of eating disorder, history of attempted suicide, use of diuretics, more severe eating disorder symptoms, desire for lower weight at admission, repeated admission, and psychiatric comorbidity predict mortality (

2–

4,

11). We address the question of which variables predict mortality when examined at a later follow-up point in this longitudinal study. Predictor variables included eating disorder symptoms, comorbidity, treatment, and psychosocial functioning assessed both at intake and through interviews conducted over the study period.

Results

Overall, 16 deaths (6.5%) were observed among the 246 participants (

Table 2).

Among the 186 individuals with a lifetime history of anorexia nervosa, 14 (7.5%) died, which translated to an annual mortality rate of 3.87 deaths per 1,000 person-years. After adjusting for age, sex, and race, the standardized mortality ratio for individuals with lifetime anorexia nervosa was 4.37 (95% exact confidence interval [CI]=2.4–7.3). Among the 60 participants with bulimia nervosa and no history of anorexia nervosa, two (3.3%) died, which translates to an annual mortality rate of 1.63 deaths per 1,000 person-years and a standardized mortality ratio of 2.33 (95% CI=0.3–8.4). When standardized mortality ratios were calculated by intake diagnosis rather than presence of lifetime anorexia nervosa, findings were consistent in that individuals with anorexia nervosa at intake had significantly elevated mortality (6.2 times the expected rate), while those with an intake diagnosis of bulimia nervosa did not (1.5 times the expected rate, with the confidence interval overlapping 1.0). Given the small number of deaths in the bulimia nervosa group, and the fact that the confidence interval for the standardized mortality ratio includes 1.0 (no elevated mortality), additional analyses focused primarily on participants with lifetime anorexia nervosa.

Of the 16 deaths, four occurred by suicide (all four of these patients had anorexia nervosa). We previously reported the standardized mortality ratio for suicide in our sample to be 56.9 (

11). With no new completed suicides in the sample, but an increased number of expected suicides in the demographically matched population since our last analysis, the standardized mortality ratio for suicide among individuals with lifetime anorexia in this sample is now substantially lower, calculated to be 25.2 [95% CI=6.9–64.5].

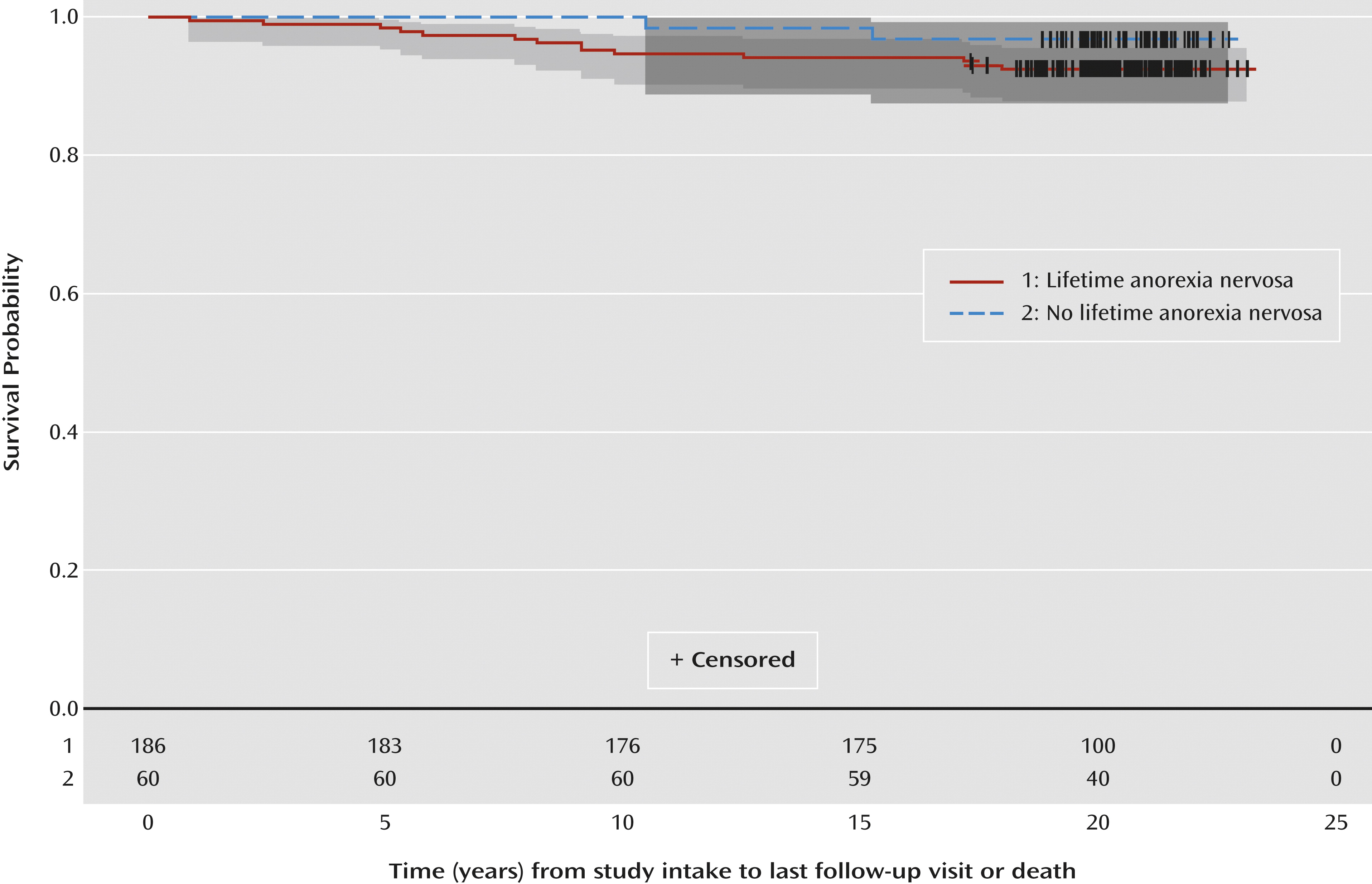

Risk of premature mortality appeared to decrease over time among individuals with lifetime anorexia nervosa. Within the first 10 years of follow-up, the annual mortality rate for this group was 5.49 deaths per 1,000 person-years, compared with 1.13 deaths per 1,000 person-years thereafter. The standardized mortality ratio also varied substantially by follow-up time. For the follow-up duration from 0 to 10 years (10/186 died), the standardized mortality ratio was 7.7 (95% CI=3.7–14.2), and for the follow-up duration >10 to 20 years (4/176 died), the ratio was 0.7 (95% CI=0.2–1.7).

When we examined the standardized mortality ratio by illness duration, we again found considerable variation. The standardized mortality ratio for those with an eating disorder for 0 to 15 years (4/119 died) was 3.2 (95% CI=0.9–8.3), and for those with an eating disorder lasting >15 to 30 years (10/67 died), the ratio was 6.6 (95% CI=3.2–12.1). In other words, the standardized mortality ratio was higher within the first decade of the study compared with the second decade and for those with a longer duration of illness. Specifically, seven of the 10 patients with a longer duration of illness died in the first decade of the study (

Table 2), although three of the four patients who died in the second decade also had a longer duration of illness. Thus, the 10 patients who died in the first decade were not the same 10 patients with >15 years of an eating disorder, suggesting that these covariates capture somewhat different information.

The number of changes in eating disorder diagnosis over the course of the study is presented in

Table 2. Our previous work indicated that over time, the majority of patients with an intake diagnosis of anorexia nervosa in the entire sample experienced crossover between the anorexia nervosa subtypes or from anorexia nervosa to bulimia nervosa; crossover was recurrent and bidirectional with the subtypes (

23,

24). In contrast, crossover from bulimia nervosa to anorexia nervosa in individuals without a history of anorexia nervosa at intake was less common (

23). It is noteworthy that two of the three individuals with an intake diagnosis of bulimia nervosa who died did not meet criteria for anorexia nervosa during the course of follow-up, nor did they have a history of anorexia nervosa at intake. It is possible that associations between mortality and eating disorder diagnoses depend on when in the course of illness diagnostic status is assessed. Importantly, however, an examination of diagnostic crossover in our predictor analyses indicated that it was not a significant predictor of mortality.

Values of covariates ascertained at intake and course variables examined as predictors of mortality are summarized in

Table 1. Although the mean age at eating disorder onset was similar between participants who were still alive at last follow-up and those who died prematurely, those who were still alive at last follow-up entered the study at a much earlier age than those who died prematurely, indicating that those who died had a longer duration of illness prior to study intake, which may reflect delays between disorder onset and seeking treatment.

As shown in the survival curve (

Figure 1), whereas individuals without lifetime anorexia nervosa were more likely to die later in the study, most deaths among those with lifetime anorexia nervosa occurred at varying times within the first 10 years of follow-up. Furthermore, while lifetime anorexia nervosa appeared to confer greater risk of mortality, the overall mortality rate was still low in both groups (survival at 20 years after study intake among individuals with and without lifetime anorexia nervosa was 92% and 97%, respectively).

Significant univariate predictors (before and after Bonferroni correction) are presented in

Table 3. After applying automated model selection separately to the significant intake, course, and last visit variables, duration of illness was the only significant intake variable to predict mortality. Among course variables, percent of weeks with alcohol abuse and percent of weeks with low body mass index (BMI) (<16) remained in the model. Among last visit covariates, alcohol abuse, BMI, and social adjustment score remained significant. To determine which of the intake, course, and last visit variables together best predicted mortality, we conducted one final automated stepwise selection, which resulted in three variables remaining significant: percent of weeks with alcohol abuse, BMI at last visit, and social adjustment score at last visit. Finally, to account for the fact that, by definition, the last study visit was closer to the time of death than to the time of the last follow-up for those still alive, we forced age at intake into the final model to account for the passage of calendar time. Both the significance and the direction of effect of the covariates were maintained in the final model after adjusting for age.

To understand the factors captured by the social adjustment score, we compared social adjustment components at last visit by mortality status. Women who died had moderate to severe impairment in employment (t=–4.92, df=160, p<0.0001), mild to moderate impairment in household functioning (t=–4.24, df=174, p<0.0001), and fair to poor interpersonal relationships with friends (t=–2.96, df=184, p=0.003) and siblings (t=–2.35, df=184, p=0.02) and were more likely to be single (Fisher’s exact p=0.07). They also had fair to poor enjoyment of recreational activities (t=–3.00, df=184, p=0.003) and low global satisfaction (t=–2.88, df=184, p=0.004). There were no significant differences in interpersonal relationships with partners or with parents.

Discussion

Our analyses revealed that patients with lifetime anorexia nervosa had higher premature mortality rates than the general population and that risk of premature death was highest in the first 10 years of follow-up and among individuals with the longest duration of illness. This finding may be explained by the fact that most of the women who died came into the study with a long duration of illness. With one exception, those who died reported an illness duration spanning 7 to 25 years before entry into the study. It may be that their deaths tended to come early in the study because they had already suffered a long period of time with an eating disorder. Thus, while mortality rates in anorexia nervosa varied based on when in the course of this longitudinal study mortality was assessed as well as by the duration of the disorder, it seems likely that chronicity is a crucial factor in premature death.

In some (

25) but not all (

26,

27) studies, the standardized mortality ratio for bulimia nervosa has been reported to be lower than that for anorexia nervosa. Interestingly, however, two of the three women with bulimia nervosa in our study who died had never been diagnosed with anorexia nervosa. Future research might investigate causes of death in bulimia nervosa, as well as potential predictors, by combining data sets in order to achieve adequate sample sizes.

The age and cause of death in this sample of patients with anorexia nervosa are noteworthy. All deaths occurred in middle adulthood, with all but three deaths occurring between ages 35 and 48 years, suggesting that for women with long-standing histories of eating disorders, middle adulthood is a particularly high-risk period for dying. Furthermore, the causes of death, with a few exceptions (e.g., amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), may have been related to eating disorder symptoms, although given the time lapse between the last interview and death, we are not able to address this issue definitively. In the case of the four suicides, the causes of death represent extreme methods with high lethality (

28).

Although a number of predictor variables were significant in univariate analyses, alcohol abuse over the course of the study and BMI and social adjustment at the last interview remained significant in multivariate analyses. Our earlier analyses at the 10-year follow-up found that longer duration of illness at intake and severity of alcohol use disorder during follow-up increased the risk of mortality (

11). Over the longer follow-up period, the degree of low weight and the social adjustment score at the last visit also emerged as significant multivariate predictors of mortality.

Social adjustment has been linked to mortality in depression and substance abuse (

29,

30). While it is difficult to know in what ways poor social adjustment may be related to mortality (i.e., directly, in concert with comorbidity, or as a reflection of eating disorder severity), our findings indicate that assessing the quality of relationships, the capacity for work and play, and the degree of impairment in psychosocial functioning is vital when working with patients with anorexia nervosa. Recent efforts examining the care of individuals with long-term anorexia nervosa are important, given how little is known about how to treat patients with a chronic eating disorder (

31,

32).

Strengths of our study include the large well-maintained sample, the long duration of follow-up, and the careful assessment of diagnoses. Limitations include that the assessment of comorbidity was limited to substance abuse and depression and that no longitudinal data were available between the last study visit and the assessment of mortality, which constituted a lengthy period in some cases. Thus, it is possible that mortality was affected by unobserved life events that occurred between the last study visit and death. Furthermore, the National Death Index does not report deaths that occur outside the United States.

In conclusion, anorexia nervosa continues to be a disorder with high mortality rates and one for which effective treatment remains elusive (

33). Our findings highlight the need for early identification and intervention and suggest that among those with a long duration of illness, particularly when substance abuse, low weight, or poor psychosocial functioning are also present, the risk for mortality increases substantially.