Generalized anxiety disorder is characterized by difficult-to-control worry, accompanied by somatic and psychological symptoms such as restlessness, sleep disturbance, and muscle tension (

1). It tends to be chronic, with an average duration of 20 years or more before presentation for treatment (

2). Its prevalence is as high as 7.3% among community-dwelling older adults and substantially higher among medical patients, making it possibly the most common psychiatric illness in late life (

3). Among older individuals, generalized anxiety disorder is associated with elevated risk of cardiovascular events (

4), increased health care utilization (

5), and poor cognitive performance (

6). It may be particularly detrimental to physical health and cognition in older adults, who have reduced cognitive and physiological reserve (

7).

Existing studies support the use of pharmacotherapy as a first-line treatment for generalized anxiety disorder in older adults, with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) as the agent of choice because of their favorable safety and side effect profiles (

8). However, pathological worry in older adults may be more treatment resistant than in younger adults. Efficacy in placebo-controlled medication trials is modest (

8). Similarly, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) does not appear to be as effective acutely with older patients with generalized anxiety disorder as it is with younger adults (

9). Theoretically, antidepressant medication and CBT involve different mechanisms and may be able to treat different components of the illness (

10,

11). Furthermore, a sequential approach in which medications are initiated before commencement of psychotherapy is likely more reflective of real clinical practice. Therefore, CBT may serve as an augmentation treatment that enhances treatment response, including long-term durability.

In practice, the combination of medication and CBT for generalized anxiety disorder is controversial. Most research suggests that combination treatments are optimal for depression (

12). A recent review also supports the efficacy of CBT as an augmentation strategy for pharmacotherapy nonresponders with anxiety disorders other than generalized anxiety disorder (

13). However, in an investigation of CBT augmentation to extended-release venlafaxine in younger individuals with generalized anxiety disorder, CBT did not improve outcomes relative to continued medication alone (

14).

Acute symptom reduction is important in generalized anxiety disorder, but studies that target treatment maintenance are essential because of the chronicity associated with this disorder. CBT is efficacious in sustaining treatment response and preventing relapse in panic disorder (

15). However, there has been little controlled research on the effect of CBT on sustained remission in generalized anxiety disorder and, to our knowledge, none in older adults (

16). In a case series, we found that the addition of CBT to SSRI treatment increased treatment response and provided long-term relapse prevention after the SSRI was tapered, although not in all participants (

17).

The objective of the present study was to examine whether sequenced treatment with escitalopram and CBT boosts acute response and prevents relapse in older adults with generalized anxiety disorder. We hypothesized that 1) augmentation of escitalopram with CBT would reduce anxiety and worry relative to continuation escitalopram alone, 2) escitalopram would reduce relapse relative to pill placebo, and 3) CBT would reduce relapse relative to pill placebo.

Method

Participants were adults ≥60 years old with a DSM-IV (

1) principal diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder, as ascertained by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (

18), and a baseline Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) (

19) score ≥17. Participants were recruited between 2008 and 2010, with the last participant completing the study in October 2011. Participants were recruited through primary care practices, mental health clinics, and advertisements at three sites: Pittsburgh, San Diego, and St. Louis. Patients with comorbid unipolar major depression or other anxiety disorders were included only if generalized anxiety disorder was the principal diagnosis. Those with a history of substance abuse or dependence were included only if they had been in full remission for at least 6 months.

Other exclusion criteria were a lifetime history of psychosis or bipolar disorder; cognitive impairment, as determined by a Mini-Mental State Examination (

20) score ≤25; current suicidal ideation; ongoing psychotherapy; and medical instability. Medical illness burden was assessed by self-report and chart review and was quantified using the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Geriatrics (

21). If participants were taking psychotropic medications, the medications were tapered off at least 2 weeks before the participant entered the study. For those who were taking benzodiazepines or prescription sleep aids, the drugs were tapered off or the participant was required to remain on a consistent, usually lower, daily dose throughout the study. The institutional review boards at all three sites approved the study, and participants provided written informed consent after receiving a complete description of the study.

Measures

Outcomes were anxiety, as measured by the HAM-A, and pathological worry, as assessed with the Penn State Worry Questionnaire (

22). The HAM-A is a 14-item interview-rated measure of anxiety primarily assessing somatic symptoms. It is considered the gold standard outcome measure in studies of pharmacotherapy treatment for generalized anxiety disorder. In this study, the intraclass correlation coefficient among raters was 0.93, indicating excellent reliability. Participants completed the HAM-A every 4 weeks during the augmentation phase and every 2 weeks during the maintenance phase.

The Penn State Worry Questionnaire (

22), a 16-item self-report questionnaire measuring excessive and uncontrollable worry, is the most commonly used outcome measure in psychotherapy studies for generalized anxiety disorder and has high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha=0.87). The questionnaire was administered at the beginning and end of the augmentation and maintenance phases.

Randomization and Study Drug Administration

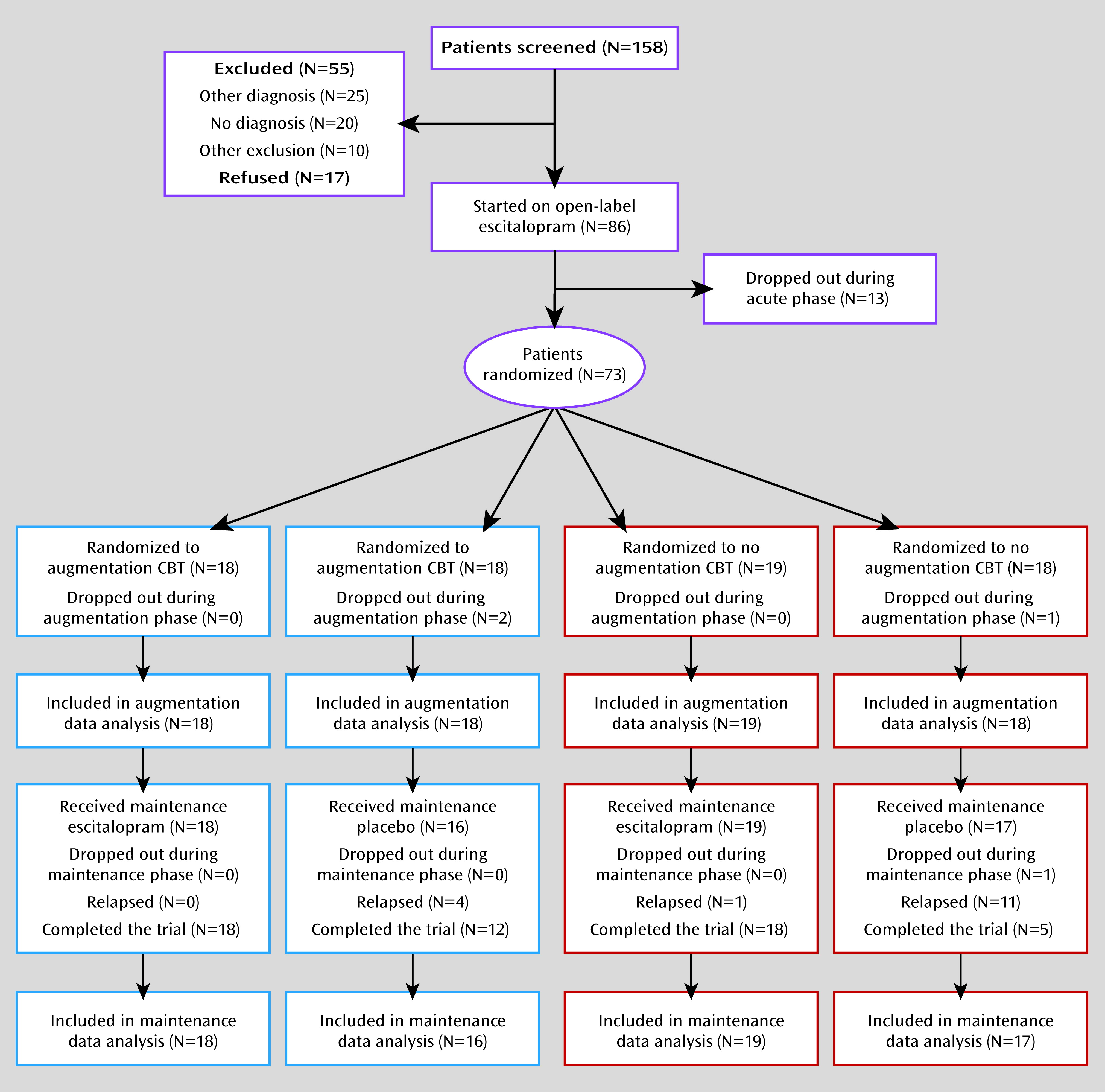

The CONSORT (

23) diagram is depicted in

Figure 1. The study provided treatment in three phases: acute, augmentation, and maintenance. In the acute phase, all participants were treated with 12 weeks of open-label escitalopram. They started at a dosage of 10 mg/day; the dosage was increased to 20 mg/day after 4 weeks as tolerated if symptoms were not improving. At the end of 12 weeks, participants who exhibited at least a 20% improvement in HAM-A symptoms were eligible to be randomly assigned to one of four conditions: 1) 16 weeks of escitalopram augmented with 16 sessions of CBT (augmentation phase), followed by 28 weeks of continued escitalopram (maintenance phase); 2) 16 weeks of escitalopram without CBT, followed by 28 weeks of continued escitalopram; 3) 16 weeks of escitalopram plus CBT, followed by 28 weeks of pill placebo; or 4) 16 weeks of escitalopram without CBT, followed by 28 weeks of pill placebo. A statistician created the randomization schedule, and the research pharmacy at each participating institution assigned individuals to conditions in the order of enrollment.

The modular 16-session CBT protocol was administered according to a detailed manual (available on request from the first author) and targeted symptoms of worry and anxiety. Some components were tailored to each participant’s presenting symptoms. All participants received modules devoted to psychoeducation/self-monitoring, relaxation training, cognitive therapy, and problem-solving skills. Those who identified a supportive local family member were encouraged to invite that person to attend one session in which the family member received education and was enlisted as an ally during the participant’s treatment. Some individuals received additional modules based on their baseline symptoms according to the following algorithm: participants who met criteria for a major depressive episode within 1 year before enrollment or had a score of 3 or 4 on the depressed mood item of the HAM-A for two consecutive assessments during the acute phase received a behavioral activation module; participants who met DSM-IV criteria for a secondary comorbid anxiety disorder at baseline within the past year or who had a score of 3 or 4 on the fears item of the HAM-A for two consecutive assessments during the acute phase received a customized CBT module on exposure therapy; participants who had a score of 3 or 4 on the HAM-A insomnia item for two consecutive assessments received a sleep hygiene module.

The CBT protocol was administered by six doctoral-level therapists (three in Pittsburgh, two in St. Louis, and one in San Diego) who were trained in the protocol by the first author. At each study site, she conducted two full-day in-services that included didactic material, videotaped demonstrations of the protocol, and role plays of the session content. Before commencing to treat randomly assigned patients, each therapist treated two pilot patients with videotapes of therapy sessions reviewed on an hour-for-hour basis by the first author. All therapists also participated in weekly conference calls led by the first author, who continued to review a sample of videotapes throughout the duration of the trial.

After completion of the augmentation phase, the escitalopram dosage for participants who were assigned to placebo for the maintenance phase was tapered according to the following schedule: 10 mg/day every 2 weeks, 5 mg/day every 2 weeks, 2.5 mg/day every 2 weeks, and then placebo for the duration of the maintenance period (or until relapse). Participants who had received CBT during the augmentation phase could receive up to three booster sessions during the maintenance phase, as needed based on self-report; 19 participants chose to do so. Relapse was defined as two consecutive assessments of 1) a HAM-A score at least 5 points greater than the lowest score achieved during the augmentation phase, to a total ≥14, and 2) meeting DSM-IV criteria for generalized anxiety disorder (except the duration criteria). Additionally, onset of a major depressive episode was considered relapse regardless of the participant’s HAM-A score.

A total of 86 participants were enrolled in the study (

Figure 1). Thirteen discontinued the study during the acute phase because of medication side effects or lack of efficacy, leaving a randomized sample of 73 participants. Three participants withdrew during the augmentation phase, two from the CBT condition (one because of dissatisfaction with the medication and one lost to follow-up after randomization but before starting CBT), and one from the medication-only condition (because of dissatisfaction with medication). One additional participant in the no-CBT placebo condition was lost to follow-up during the maintenance phase. Thus, 69/73 (95%) randomly assigned participants completed the entire 13-month protocol. Analyses were conducted on an intent-to-treat basis using data from all randomly assigned participants, including dropouts, for the augmentation analyses and from all participants who entered the maintenance phase for the relapse analyses.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.), and STATA, version 9 (StataCorp, College Station, Tex.). Group differences at baseline were examined using one-way analysis of variance for continuous variables and the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. The same analyses were conducted to examine possible differences among sites. In order to investigate which covariates should be included in the models, we examined the effects of all variables that differed either among treatment groups or among sites. Those that did not have an effect on outcomes were not included in the final models.

We examined the augmentation effect of CBT on cumulative treatment response, defined two ways based on previous research as follows: achieving a HAM-A score ≤10 (

24) and experiencing a decrease ≥8.5 points on the Penn State Worry Questionnaire (

25). For HAM-A scores, we used Kaplan-Meier survival analysis to compare the survival functions of the escitalopram plus CBT group with those of the escitalopram-only group using the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards regression models were also fitted to examine the effect of CBT while controlling for HAM-A score at the beginning of augmentation. Because only two time points were available for the Penn State Worry Questionnaire data, making Cox proportional hazards models inappropriate, we examined the augmentation effect of CBT on the questionnaire treatment response using logistic regression, controlling for questionnaire scores at the beginning of augmentation. Participants who dropped out during the augmentation phase (N=3) were considered to be nonresponders.

We also examined improvement in anxiety and worry symptoms using linear mixed models. We modeled the treatment-by-time interaction over the augmentation phase for each outcome separately. Each model included the week 12 HAM-A or Penn State Worry Questionnaire score to control for baseline anxiety or worry severity at the time of randomization, time (weeks), treatment condition (CBT versus no CBT), and the time-by-treatment condition interaction. The covariance of the outcomes was unstructured. A restricted maximum likelihood approach was used to fit the proposed model. The Cohen’s d effect size of CBT at week 28 for all outcomes was calculated using the estimated means and standard errors of the linear mixed models.

The primary analytic strategy during the maintenance phase was comparison of cumulative incidence of relapse across the four conditions. Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were conducted to examine relapse rates. The participant who dropped out during the maintenance phase was considered to have relapsed. The log-rank test was conducted to compare the survival functions among groups. First, an omnibus test examined whether any differences existed among the four groups. We then examined effects among conditions to determine whether medication or CBT was more effective than placebo in preventing relapse, as well as whether there were differences between maintenance medication without CBT and CBT without medication. Cox proportional hazards regression models were also run to control for potential covariates, as well as HAM-A score, at the start of maintenance.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the treatment groups are summarized in

Table 1. The four groups did not differ on demographic variables or anxiety or worry level at pretreatment. The one statistically significant group difference was that the group assigned to the placebo arm had a higher proportion of participants with a current comorbid anxiety disorder at baseline (p=0.03). However, presence of a comorbid anxiety disorder did not predict outcomes on the HAM-A or Penn State Worry Questionnaire in the augmentation phase or on relapse in the maintenance phase; therefore, this variable was not included as a covariate in subsequent analyses.

St. Louis participants were, on average, slightly older (mean age, 71.6 years [SD=8.4] compared with 66.5 years [SD=3.7] for the Pittsburgh site and 68.9 years [SD=7.6] for the San Diego site; F=3.73, df=2, 70, p=0.03), less educated (mean education,14.3 years [SD=2.7] compared with 15.5 years [SD=2.9] and 16.4 years [SD=2.6] for the Pittsburgh and San Diego sites, respectively; F=4.82, df=2, 70, p=0.02), and reported less severe pathological worry (mean Penn State Worry Questionnaire score, 49.9 [SD=12.1] compared with 59.9 [SD=9.6] and 56.6 [SD=9.7] for the Pittsburgh and San Diego sites, respectively; F=4.38, df=2, 70, p=0.02) than participants from the other two sites. The San Diego participants reported a more recent age at onset than those from the other sites (mean age, 55.2 years [SD=35.4] compared with 28.9 years [SD=27.8] and 37.7 years [SD=37.7] for the Pittsburgh and St. Louis sites, respectively; F=3.91, df=2, 70, p=0.03). There were no differences across sites in any other variables. We found no effects of age, education, or age at onset on results, and thus these variables were not included as covariates. We did not find an effect of initial Penn State Worry Questionnaire scores on HAM-A outcomes in the augmentation phase or on relapse during the maintenance phase, and thus the questionnaire was not included as a covariate in these analyses. Questionnaire scores at week 12 were controlled for in the augmentation analyses.

Augmentation

For response according to the HAM-A, the cumulative incidence of response did not differ significantly between the escitalopram-plus-CBT group (75.0%, 95% confidence interval [CI]=60.2–87.6) and the escitalopram-only group (67.6%, 95% CI=52.5–81.8; log-rank χ2=0.30, df=1, p=0.58). Cox proportional hazards regressions suggested that CBT was not associated with response after controlling for HAM-A severity at the start of the augmentation phase (hazard ratio=1.10, 95% CI=0.64–1.91, p=0.72). For response according to the Penn State Worry Questionnaire, after controlling for score at the start of augmentation, participants who received CBT were approximately three times more likely to respond by the end of augmentation than those who did not receive CBT (odds ratio=3.19, 95% CI=1.00–10.14, p<0.05).

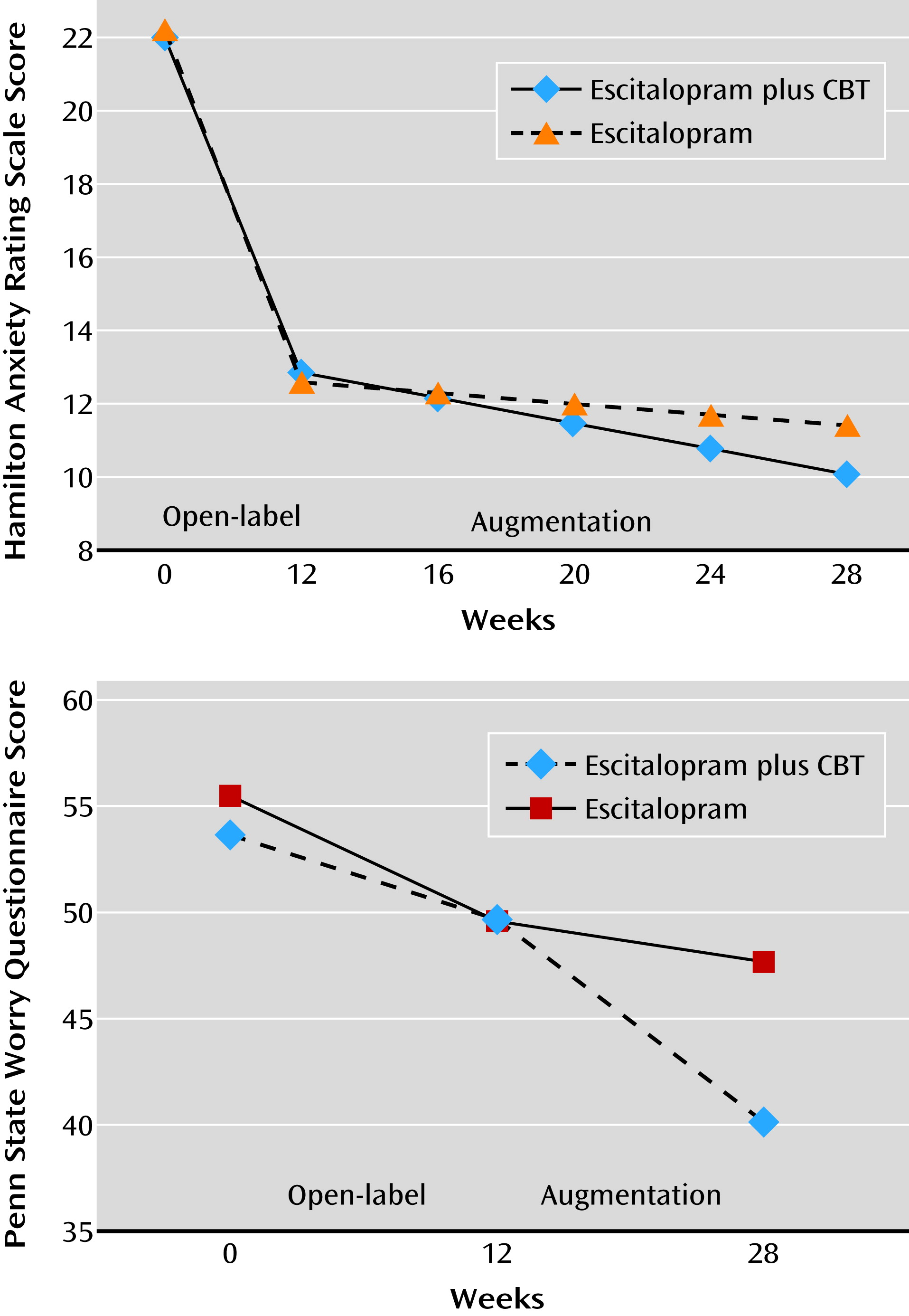

With respect to symptomatic improvement, participants who received escitalopram combined with CBT in the augmentation phase exhibited greater improvements in pathological worry, as measured by the Penn State Worry Questionnaire, than those who received escitalopram only (linear mixed-effects model, β=−0.48, 95% CI=−0.84 to −0.11, p=0.01) (

Figure 2). The effect size of CBT on worry symptoms was medium to large (Cohen’s d=0.60). Participants who received CBT did not exhibit greater improvements in anxiety symptoms, as measured by the HAM-A, over time (β=−0.10, 95% CI=−0.23 to 0.04, p=0.15; Cohen’s d=0.27).

Because in clinical practice only patients who do not respond to a first-line treatment would be offered an augmentation treatment, we reran all analyses with data only for the 34 participants who remained symptomatic at week 12 (i.e., those with a HAM-A score ≥14). In this subsample, 52.6% of those who received CBT, compared with 26.7% of those who did not, achieved response according to HAM-A criteria (log-rank χ2=2.21, df=1, p=0.14). The effect of CBT on Penn State Worry Questionnaire response was no longer statistically significant in this small subgroup, although the magnitude of the odds ratio increased (odds ratio=4.99, 95% CI=0.71–35.08, p=0.11).

Maintenance

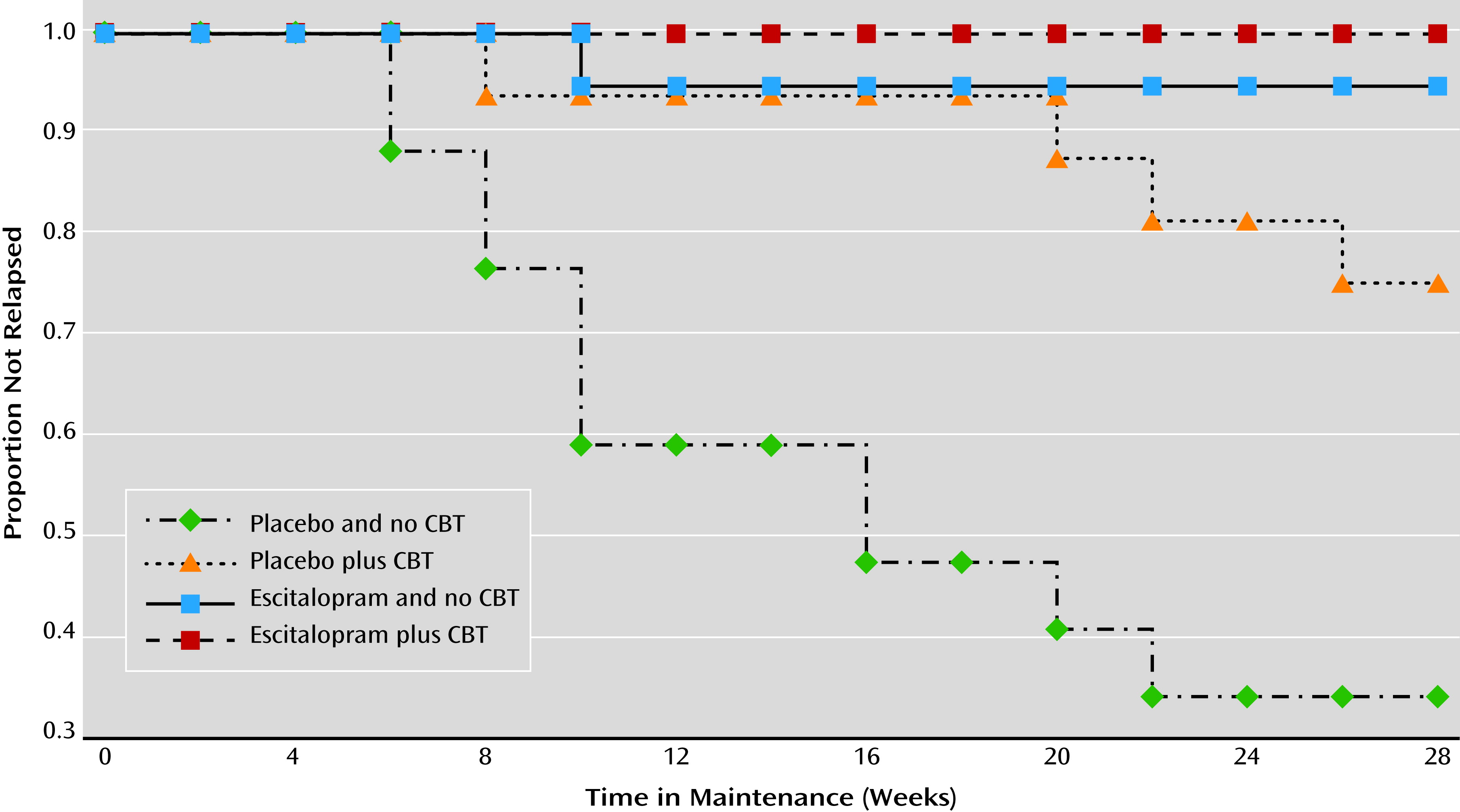

Estimates of the cumulative incidence of relapse for the four treatment groups are displayed in

Figure 3. The log-rank comparison test suggested that the incidence of relapse differed across the four conditions (log-rank χ

2=32.67, df=3, p<0.001). Regardless of CBT status, participants assigned to maintenance escitalopram had a significantly lower relapse rate (2.7%, 95% CI=0.3–17.7) than those receiving placebo (46.1%, 95% CI=30.8–64.5; log-rank χ

2=18.50, df=1, p<0.001). Because the effect of medication on preventing relapse was so strong (only one participant receiving maintenance medication relapsed), rather than examine the main effect of CBT in the full sample, we examined the effect of CBT only within the group receiving placebo. Participants taking placebo who received CBT had lower rates of relapse (25.0%, 95% CI=10.2–31.9) than those who did not (66.4%, 95% CI=44.0–87.1; log-rank χ

2=6.92, df=1, p=0.009). The difference in relapse rates between those receiving maintenance medication with no CBT (5.3%) and those who received CBT but no maintenance medication (25.0%) was not statistically significant (log-rank χ

2=2.60, df=1, p=0.11).

Finally, Cox proportional hazards regression models were run such that the HAM-A score at the start of the maintenance phase was added as a covariate to examine relapse rates. Adding the week 28 HAM-A score did not change the statistical significance of the results for CBT (hazard ratio=0.23; 95% CI=0.07–0.76, p=0.02) or for medication (hazard ratio=0.05; 95% CI=0.01–0.41, p=0.005).

Ordinarily, only patients who achieve response are enrolled in maintenance trials. We therefore reran analyses for the 35 participants whose HAM-A scores were ≤10 at the end of the augmentation phase. The Kaplan Meier log-rank test among the four groups remained significant (log-rank χ2=9.52, df=3, p=0.02). None of the participants receiving maintenance medication relapsed, compared with 34.0% of those receiving placebo (log-rank χ2=9.85, df=1, p=0.002). Among the participants receiving placebo, 25.0% of those who received CBT relapsed, compared with 42.9% of those who did not (log-rank χ2=0.68, df=1, p=0.41).

Discussion

A sequence of SSRI medication followed by augmentation with CBT led to higher rates of response on a measure of worry severity, although not on a measure of anxiety symptoms, in older adults with generalized anxiety disorder. Maintenance medication was highly protective against relapse. CBT was also protective; three-quarters of participants who received CBT were able to discontinue their medication and remain well.

This study suggests that adding CBT may be a useful treatment option for some patients after starting an SSRI as standard first-line treatment for late-life anxiety disorder. First, the addition of CBT reduces worry severity, particularly when the SSRI is insufficient to bring about a response. Second, a maintenance SSRI prevents relapse. Finally, CBT also prevents relapse, potentially allowing some individuals to eventually taper off the SSRI and remain well. These findings are important given the high prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder in older adults and the paucity of alternative strategies. CBT as monotherapy has proven disappointing (

8,

9), and the most common strategy in current use, benzodiazepine treatment, has a poor risk-benefit ratio (

26) because these medications increase the risk of falls and fractures (

27), disability (

28), and cognitive decline (

29) in elderly individuals. In contrast to such risks, a sequence of an SSRI followed by augmentation with CBT may be an optimal therapeutic approach in terms of efficacy and safety for older patients with generalized anxiety disorder, particularly those who express concerns about long-term use of psychotropics.

There remains controversy regarding the value of CBT augmentation of antidepressant medication in anxiety disorders, with some but not all studies demonstrating benefit with CBT in this context (

13,

14,

30,

31). We are unaware of any other study that has demonstrated the relapse prevention benefits of CBT augmentation in generalized anxiety disorder; ideally, these findings should be independently confirmed.

With respect to the relapse prevention benefit of maintenance SSRIs in generalized anxiety disorder, the results of our study agree with findings in young adult and middle-aged samples. A meta-analysis of studies using escitalopram, duloxetine, and paroxetine in younger samples found an 80% reduction in the odds of relapse associated with medication compared with placebo (

32). Other studies found similar results for pregabalin (

33), quetiapine (

34), and extended-release venlafaxine (

35). Across these investigations, the range of relapse rates for patients receiving placebo was 39%–65% (compared with 66% for the placebo-only arm in the present study), compared with relapse rates of 10%–42% for those receiving active treatment (compared with 5% for participants receiving escitalopram and 25% for those who underwent CBT in our study). Therefore, the data are consistent: just as it does in major depressive disorder (

36), maintenance SSRI prevents relapse in generalized anxiety disorder, regardless of age.

It is possible that different symptoms may respond to different therapeutic modalities, as suggested by a previous investigation of generalized anxiety disorder treatment (

37). Somatic anxiety symptoms, as measured by the HAM-A, may be more sensitive to change with pharmacotherapy. Pathological worry, by contrast, may respond better to CBT. If so, using the principle of personalized medicine, referral to CBT may be particularly appropriate for chronically anxious older patients who report improvement in physiological symptoms but continue to report excessive worry following a trial of antidepressant medication.

Alternatively, the fact that we found results on the Penn State Worry Questionnaire but not on the HAM-A may have been an artifact of our selection criteria, which resulted in ceiling effects for the latter measure. It is also possible that differing results could have been driven by assessment modality (self-report versus clinician-administered) rather than by content (worry versus somatic anxiety symptoms).

Limitations of our study are the small sample size; lack of an active control condition for CBT; lack of a global outcome measure, such as the Clinical Global Impression improvement rating; and the fact that participants were only followed for 7 months during the maintenance phase. Power to detect a significant augmentation effect of CBT on HAM-A scores was only 0.30. A sample of 278 (136 per group) would have been required to detect the effect size of 0.27 that we obtained. Replication of these results, over a longer duration, would strengthen the evidence base for treating chronic worry and anxiety in older individuals.

In summary, this study of sequenced SSRI and CBT augmentation for older adults with generalized anxiety disorder provides support for the treatment-enhancing effects of CBT, as well as the relapse prevention benefits of both maintenance SSRI and CBT. These findings offer patients and providers good strategies for achieving and maintaining optimal response from this common and deleterious anxiety disorder.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Caroline Ciliberti, Michelle Costantino, M.P.A., Sean Engelkemeyer, Ph.D., Lawrence Glanz, Ph.D., Debora Goodman, Deborah Greenwald, Ph.D., Kathleen McChesney, Psy.D., Sara Parent, M.A., Rachel Scullin, M. Katherine Shear, M.D., Grace Snell, M.S.W., Sara Snyder, Melinda Stanley, Ph.D., Jill Stoddard, Ph.D., and Chelsea Toner, M.A., for their assistance.