For historical reasons, Switzerland uses a militia army for its defense. Between training courses, as well as during service on weekends, the militia soldier must store his gun at home, a situation unique in Europe. As a consequence, army-issued guns are available in Swiss homes throughout the year. When soldiers have completed their militia service, they may buy their service weapon for a small fee. Switzerland has a population of 7.5 million inhabitants who own a total of approximately 2 million firearms; thus, approximately every other household owns a gun (

1). Most soldiers and veterans have this single military gun and do not possess other firearms. Following the general effect that availability of means predicts the rate of suicide by that means (

2,

3), many young men in Switzerland who die by suicide use a gun (

4). Between 1995 and 2003, 39% of all suicides among men ages 18–43 in Switzerland were carried out using a gun (data from the Swiss Federal Statistical Office). The military gun thus plays an important role in suicide in Switzerland.

Compared with other European countries, firearm laws in Switzerland are generally less restrictive. All Swiss citizens are allowed to purchase firearms, and a license is required for only a minority of those, but no laws regarding licenses have been implemented for many years; firearm laws regarding private guns were constant during the period we examined in this study.

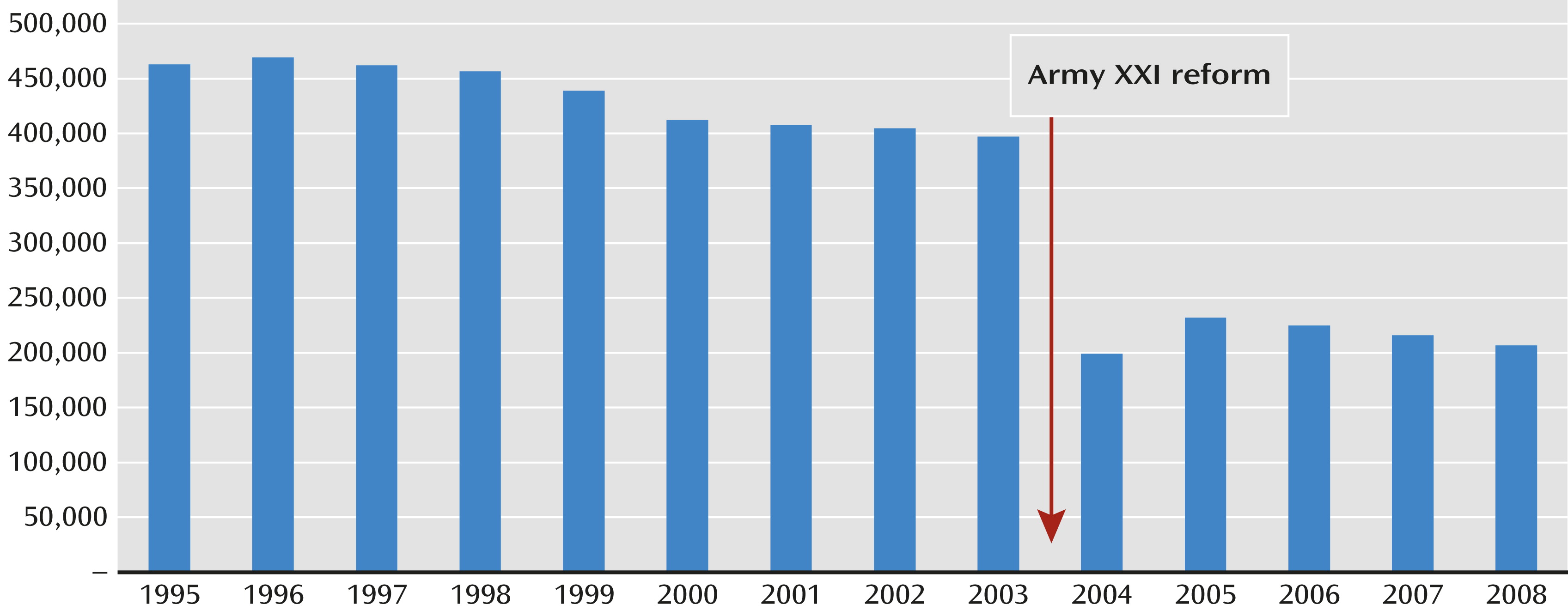

In 2003, the Swiss army was restructured by new legislation commonly referred to as “Army XXI.” The reduction of troops from approximately 400,000 to 200,000 (

Figure 1), mainly achieved by early discharges, had a significant impact on the availability of military guns. With the Army XXI reform, the discharge age changed from age 43 to age 33. In addition, the percentage of men recruited was lowered. A third aspect of the reform was an increase in the fee soldiers pay to purchase their military gun after service. Moreover, a gun license has been required since then. These factors together may have had a delayed effect on gun availability after a lag of several years.

Given these circumstances, we expected that the Army XXI reform might have had an impact on the numbers of firearm suicides in Switzerland. The reform may be considered a natural experiment that allows the testing of whether restrictions on guns were associated with a decline in the firearm suicide rate. We hypothesized that the reform might also have attenuated the general suicide rate in the affected group (men ages 18–43).

Restriction of means is one of the few evidence-based suicide prevention measures known in public health (

5–

9). Most studies on restriction have focused on the decrease in the number of firearm suicides (

10–

15), and only a few have examined the overall suicide rate (

16,

17). Other studies have pointed to a method-substitution effect in which other suicide methods substitute for firearm suicide after restriction has been implemented (

18–

20). It is unknown what proportion of total suicides may be prevented through restriction-of-means interventions. The magnitude of the method-substitution effect will depend on several factors, particularly on the suicide method itself. Suicide by gun has the highest lethality of all suicide methods (

21) and is often carried out as an impulsive act. Therefore, we additionally expected that the method-substitution effect would be relatively low for an intervention that reduces firearm suicide compared with other suicide methods.

Results

General Prevention Effect and Method Substitution

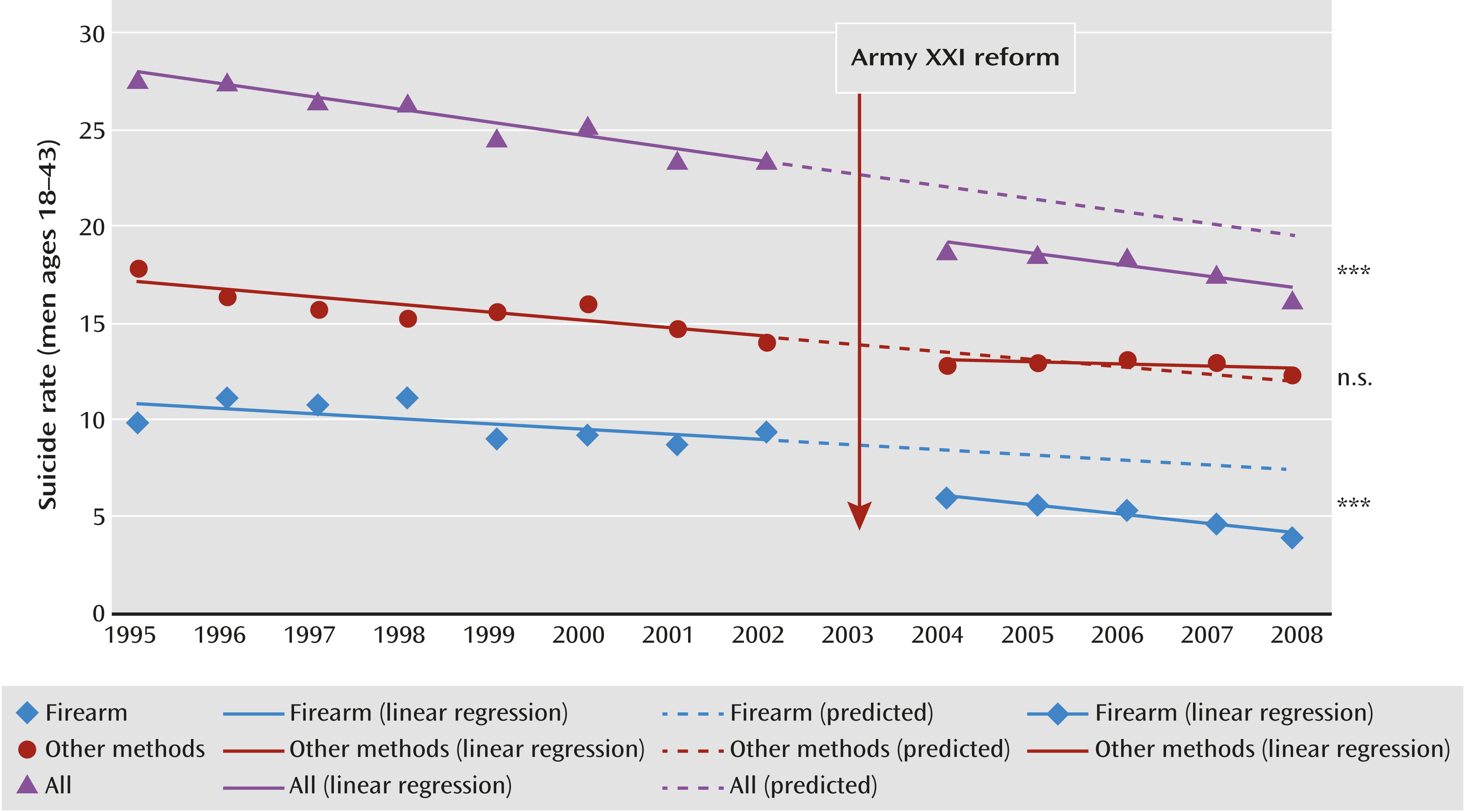

The overall suicide rate, the rate of suicide by firearm, and the rate of suicide by other methods all decreased throughout the preintervention period (linear regression: F=8.02, df=1, 95, p=0.006) in the affected age group (men ages 18–43). The regression model showed a superior fit for this linear (negative) trend compared with models that included quadratic or cubic terms. Therefore, the forecasts (expected monthly values) were calculated on the basis of a linear regression. Compared with these forecasts, real observed values were lower for both the overall suicide rate (t=4.96, p<0.001; mean difference=2.16, SD=3.32) and the rate of firearm suicide (t=11.81, p<0.001; mean difference=2.64, SD=1.70). No significant increase was found for suicide by other means after the intervention (t=−1.27, n.s.; mean difference=−0.48, SD=2.85). On the basis of a composite non-firearm suicide rate, the data did not indicate method substitution. However, when analyzing all suicide methods separately, we found a significant increase in suicide by “jumping in front of a moving object” (usually railway suicides) (t=−3.43, p<0.01; mean difference=−0.42, SD=0.93), yet no signs of substitution in any of the other commonly employed methods (hanging, drug overdose, jumping from a height). All results were Bonferroni-corrected to account for multiple significance testing (

Figure 2).

The data indicate that 2.16 fewer suicides per 100,000 inhabitants than expected (95% CI=1.29 to 3.03) occurred in the overall suicide rate of men ages 18–43. Suicides by firearm decreased, against forecasts, by 2.64 per 100,000 (95% CI=2.19 to 3.08), which, on the basis of cohort size, corresponds to 36.7 men in total. There was an increase of 0.48 per 100,000 in suicides using other methods (95% CI=−0.27 to 1.22), or 6.7 men in total. Overall, assuming that the suicide rates of different methods are linked to each other, it can be estimated that 22% of the men in this age cohort who died by suicide substituted a different method for firearms. Hence, a partial method substitution was supported, which amounts to approximately 30 men in the 18–43 age group in Switzerland each year who did not die by suicide but might have otherwise.

Alternative Methodological Approaches

The Poisson regression approach models the monthly frequencies of suicide events (firearm suicides in men ages 18–43). Suicide frequency was significantly predicted (χ2=143.5, df=3, p<0.0001) in the multiple regression model, with intervention (χ2=9.99, p=0.002) and time (χ2=9.41, p=0.002) but not cohort size as significant predictors.

The second approach, based on the autocorrelation function, showed that autocorrelations up to lag 6 (i.e., half a year) were significant. We therefore determined the AR(6) model of the suicide time series and computed the residuals of this model, from which all trends and autocorrelative time dependencies were removed. The regression of intervention and cohort size on these residuals again showed significant prediction by intervention (t=2.10, p=0.037) but not by cohort size.

In our third approach, comparing all 33 surrogate tests, we found that the factual model yielded the best model as judged by maximum likelihood statistics; the factual model also resulted in the highest chi-square value of the core predictor (intervention) and the highest whole-model chi-square. None of the dislocated surrogate interventions, and hence none of the random fluctuations in the monthly suicide numbers from previous years, resulted in a better model than the actual Army XXI reform intervention (

Table 1).

Effect of Unemployment and Immigration

The time series of unemployment as well as that of suicides both decreased in the period 1995–2008. Time series analysis showed that monthly unemployment rates were not significantly associated with suicide. The lag 1, lag 2, and lag 3 impact of unemployment on suicides was nonsignificant. Hence, we found no evidence of a confounding effect of unemployment in men of the relevant age group in the relevant time period.

Addition of the number of male immigrants to Switzerland as a further predictor in the Poisson regression models of suicide frequency in men ages 18–43 again resulted in significant prediction (χ2=135.6, df=4, p<0.0001) of the multiple regression model. Intervention was the only significant predictor (χ2=4.79, p=0.029); the predictors immigrant number, time, and cohort size contributed nonsignificantly. Thus, we found no evidence of an explanatory effect of immigration numbers on suicide frequency.

Long-Term Effect of the Intervention

We detected neither attenuation nor an increase of the reduction effect over the years after implementation of the Army XXI reform. The trends in the differences (forecast minus observed data) during the postintervention months were nonsignificant, indicating no time-related changes of the effects associated with the intervention. This was true for the general suicide rate, the rate of suicide by firearm, and the rate of suicide by other methods. Thus, we found that the observed reduction effect was maintained after the intervention.

Comparison Groups

The female comparison group showed no statistically significant changes in rate of suicide by firearm (mean difference=0.03, SD=0.53), the rate of suicide by other means (mean difference=−0.29, SD=2.22), or the overall suicide rate (mean difference=−0.26, SD=2.35). Observed time series of these variables were therefore not significantly different from forecast values. The comparison group of men ages 44–53 showed a statistically marginal decrease in rate of suicide by firearm (not significant after Bonferroni correction; mean difference=1.43, SD=4.23). We found a significant increase in other methods in this comparison group (t=−4.85, p<0.001; mean difference=−4.06, SD=6.38), most prominent in railway suicides (t=−9.37, p<0.0001; mean difference=−2.13, SD=1.73). The group’s overall suicide rate increased nonsignificantly (not significant after Bonferroni correction; mean difference=−2.63, SD=7.95).

As in the directly affected age group of men, we applied the alternative Poisson regression approach to model the monthly frequencies of firearm suicide events in men ages 44–53 and in women ages 18–43. In the older male group, suicide frequency was significantly predicted (χ2=41.2, df=3, p<0.0001) in the multiple regression model; time was also a predictor but fell short of significance (χ2=3.18, p=0.07). Intervention and cohort size were nonsignificant predictors. The Poisson regression model for the female group was marginally significant (χ2=6.9, df=3, p=0.07), yet none of the predictors (time, intervention, and cohort size) were significant. Hence, consistent with the interrupted time series approach, both comparison groups showed no significant effect from the Army XXI reform intervention. Addition of immigration numbers to these regression models resulted in analogous findings: none of the predictors, including immigration number, was significant.

Discussion

The Army XXI reform was a legislative intervention introduced in Switzerland in 2003 with the goal of restructuring and resizing the Swiss army. This legislation had, as a side effect, a major impact on the availability of firearms throughout Switzerland, allowing us to estimate the potential effect of a nationwide restriction-of-means intervention on suicide rates. We found a marked reduction in firearm suicide in the directly affected male age group after the intervention. The frequency of firearm suicide in Switzerland had, however, started declining well before the Army XXI reform. These long-standing trends were taken into account by forecasting, and the population of affected men still showed substantial reductions in suicide rates, beyond the forecasts, in the postintervention period. Our analyses therefore support the conclusion that suicide rates have decreased as a consequence of reduced firearm availability in the wake of a nationwide law. These primary analyses were based on the method of interrupted time series, modeling suicide rates per 100,000 residents per year and assuming normal distribution of suicide rates. We conducted extensive alternative statistical approaches based on the raw data, that is, the suicide counts in the age cohorts of interest. The models of suicide counts assumed Poisson-distributed data. These Poisson regressions yielded results that supported those of the interrupted time series approach throughout: Firearm suicides in men ages 18–43 were statistically linked to the Army XXI reform, whereas those of the comparison groups were not. Surrogate testing additionally suggested that the decrease is not likely an artifact due to random fluctuations of suicide events. The alternative statistical approaches corroborate the validity of the results of the interrupted time series.

The reduction in firearm suicide linked to restricted arms availability is consistent with numerous other studies investigating this phenomenon (

11–

15). More importantly, no significant substitution effect was found when all suicide methods except firearms were collapsed, which is in line with several other studies (

16,

17). However, when analyzing these methods in detail, the data suggest that some suicides possibly reflect substitution of firearm suicide with jumping in front of a moving object (mainly railway suicides). Thus, interpreting the results cautiously, we found a partial method-substitution effect in which some selective substitution may have occurred. The reduction of suicides was sustained throughout the postintervention period, with regard to both the overall suicide rate and the firearm suicide rate.

The postulated quantitative reduction of suicides among men ages 18–43 must be considered an important result. Under the assumption that these data are in fact linked, more than three-fourths of the risk group prone to firearm suicide did not switch to another suicide method. Thus, after the Army XXI reform intervention, approximately 30 fewer young men died by suicide each year in Switzerland.

The female comparison group showed no statistically significant deviations from the predicted values in the general suicide rate, the rate of suicide by firearm, or the rate of suicide by other means. The results for the female comparison group support the adequacy of the chosen statistical method, interrupted time series analysis. The older male comparison group (ages 44–53) also showed no statistically significant effect regarding the firearm suicide rate and the general suicide rate. These findings support the conclusion that the Army XXI reform mainly had a specific effect on the affected age group. However, Bonferroni-corrected results of the male comparison group regarding firearm suicide were close to statistical significance. We therefore cannot exclude the possibility that some effect was also present for the male comparison group. This may be attributed to the fact that military guns stored at home are also accessible to other family members.

The significant increase in other suicide methods in the older male group is more difficult to interpret. It suggests that other factors may have had an impact on the other age cohort, independent of the Army XXI reform. Some suicide methods may have become more prevalent in Switzerland, such as railway suicide and assisted suicide in older age groups. In this light, the increase in railway suicides in the study group may be speculatively linked not exclusively to method substitution but also to other societal factors.

Although our analyses suggest, on the basis of observational data, that the Army XXI reform was associated with a reduction in suicide rates, these post hoc analyses cannot verify a causal relationship between the intervention and the reduction. Investigating prevention with respect to methods other than firearms is desirable but may prove difficult because the necessary circumstances may not present themselves. It is rarely possible to discourage a common suicide method within a whole country, and in a short period of time, as appears to have occurred by the single intervention of the Army XXI reform. In the absence of favorable circumstances, any effects may be shrouded by the natural variance of suicide rates (statistical noise). Yet suicide by gun is often carried out as an impulsive act (

32). Assuming that the observed reduction in suicide rates was indeed linked to the Army XXI reform, the results may be best applied to other methods that are also used impulsively, such as jumping from a height or in front of a train (

33).

Other limitations should be considered as well. The observed values may be attributed to other factors. The military discharges themselves may have reduced stress in young men. The Army XXI reform reduced the number of militia soldiers, but data on the effective number of guns in households were unavailable. However, very likely the number of soldiers in Switzerland is highly correlated with the number of weapons. One may consider other causes of reducing the prevalence of firearm suicide. Initiatives such as the Alliance Against Depression (

34) were staged. Their influences will be small, however, as the majority of initiatives were launched after 2008, and none had a specific focus on firearm suicide. Moreover, studies have shown that such initiatives often do not reach males (

35). In October 2007, the Swiss Federal Council decided to stop the distribution of ammunition to soldiers and started a process to have all previously issued ammunition returned. Our study includes data through the end of 2008, so the effect of restricted ammunition may have exerted some influence on the final months included in our study. Another social development that may have affected suicide rates is immigration (

27). Suicide rates may differ between immigrant and native citizens; for example, Turkish immigrants (who are a large immigrant group in Switzerland) have a low suicide rate in Germany (

36). Immigrants do not have legal access to army weapons. However, there was no marked change in the trend of immigration to Switzerland, so a linearly increasing confounder due to immigration would have been adjusted by the interrupted time series method. Empirically, we considered immigration numbers as a possible confounding variable in regression models and found no significant predictive value of immigration for suicide numbers in the affected cohort and the comparison cohorts. Hence, the rising number of immigrants cannot account for the decreasing suicide rates. Another limitation of the study is that accidental deaths may have been attributed to suicide. This would be true for both the preintervention and postintervention periods, however. It seems unlikely that such aspects systematically influenced our results. A general limitation of the study is that we did not investigate the influence of the Army XXI reform on homicide rates, as army weapons play a major role in violent deaths in households in Switzerland (

37).

The Army XXI reform was not designed or implemented as a suicide prevention effort. Paradoxically, this is a property common to other highly effective interventions in this field, such as the detoxification of household gas in the 1960s (

38) and the introduction of catalytic converters in cars (

39). The fact that suicide prevention may have occurred as an unintended consequence allows us to exclude the possibility that the reduction in suicide rate was due to causes other than firearms restriction, such as a greater awareness of the suicide problem. This endorses the validity of the results.