T

o the Editor: A 2010 meta-analysis (

1) concluded that reboxetine, a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor approved for the treatment of depression in several countries worldwide, is “an ineffective and potentially harmful antidepressant.” Wide variation in the side effect profiles of therapeutic drugs makes the risk-to-benefit ratio for populations difficult to interpret. Greater understanding of the factors underlying such variation may facilitate the more effective selection of patients at lower risk of adverse events. For instance, both the therapeutic and adverse effects of reboxetine derive from enhanced norepinephrine transmission mediated by adrenergic receptors (adrenoceptors). The α

2 group of adrenoceptors influences a range of human physiological functions, and the α

2B subtype plays a specific role in the peripheral regulation of cardiovascular responses (

2). We therefore hypothesized that a functional deletion polymorphism in the gene coding the α

2B adrenoceptor (ADRA2B) (

3) that has been linked to individual differences in norepinephrine signaling (

4,

5) may mediate the adverse cardiovascular effects of norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors such as reboxetine.

In a study approved by the Brighton and Sussex Medical School Research Governance and Ethics Committee, 58 healthy male Caucasian volunteers 18 to 32 years old were genotyped for the ADRA2B deletion polymorphism. We recorded baseline cardiovascular parameters (pulse rate and systolic and diastolic blood pressure) and the severity of adverse effects (dry mouth, anxiety, sweating, palpitations, nausea, dizziness, irritability, and tiredness) using a visual analogue scale before administering either 4 mg of reboxetine (N=30) or placebo (N=28), using a double-blind procedure. Two hours later, in keeping with the t

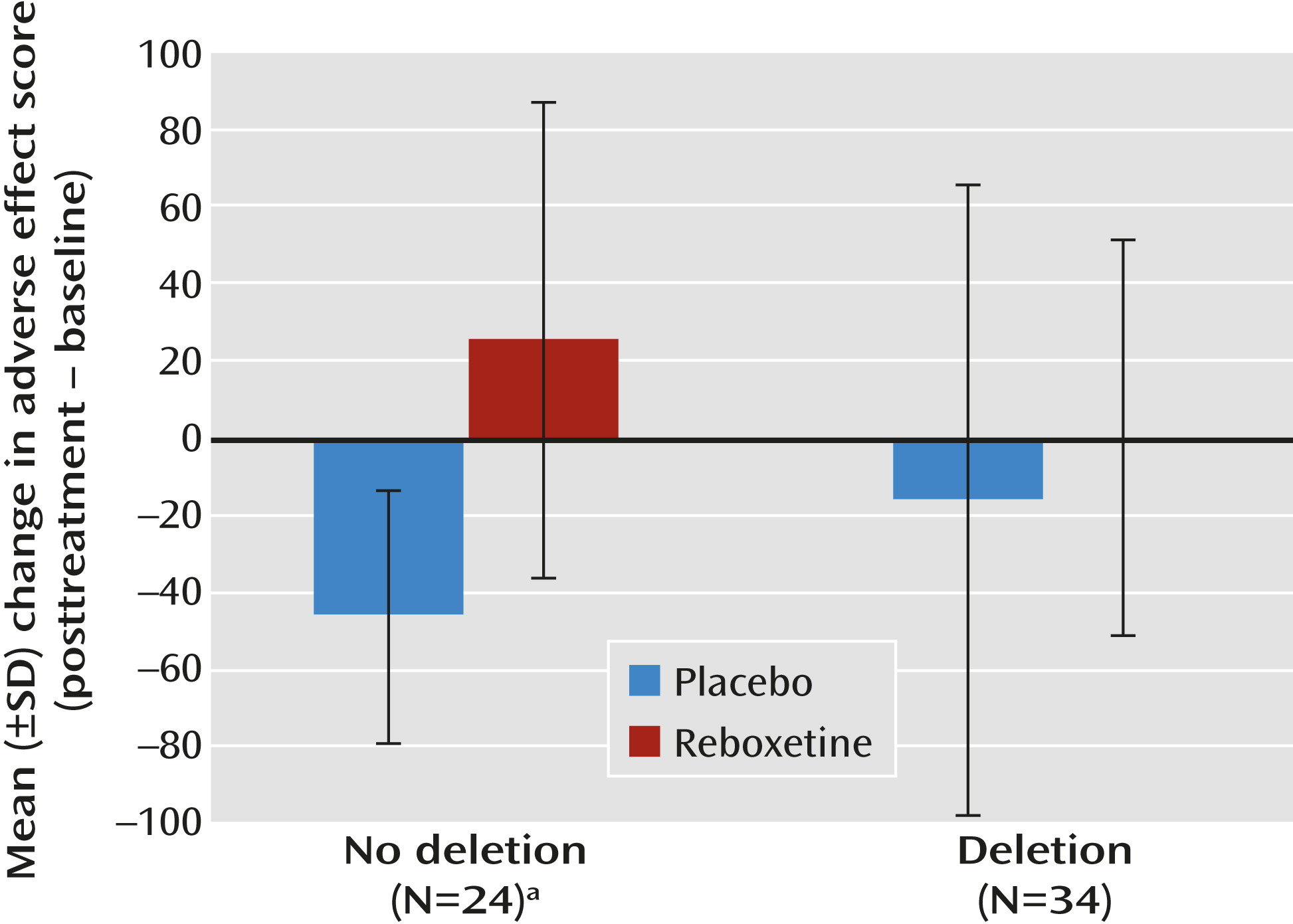

max for reboxetine, we repeated cardiovascular and adverse effect measures (posttreatment). In addition to a main effect of reboxetine on pulse rate (F=7.6, df=1, 53, p=0.005) and total adverse effect score (F=11.4, df=1, 53, p=0.001), we observed a significant interaction between ADRA2B genotype and the severity of posttreatment adverse effects (F=5.0, df=1, 53, p=0.03), while correcting for baseline measurements. In participants lacking a copy of the ADRA2B deletion variant (N=24; 12 each in the reboxetine and placebo groups), reboxetine was associated with a significant increase in adverse effect scores from baseline (t=3.7, df=22, p=0.001) that was absent in participants with at least one copy of the deletion allele (N=34; 18 in the reboxetine group and 16 in the placebo group) (see

Figure 1). In the reboxetine group, the number needed to treat (by genotyping) to prevent an increase of ≥50 in the adverse effect score was 2.6.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of a genetic moderator of severity of adverse effects following a single dose of reboxetine. It is also one of the first reports of a genetically determined pharmacodynamic marker of psychotropic drug adverse effects (

6). Further studies to replicate and extend our findings (including chronic dosing and patient populations) and to clarify the underlying mechanisms will be necessary for clinical application. However, the utility of such data is likely to extend beyond reboxetine to other selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors currently on the market (atomoxetine) and in late-stage development (edivoxetine).