Past History

The troubles in Ms. A’s life started about 8 years earlier when her husband, a soldier, drank too much at a family gathering for a celebration, became intoxicated, and shot at family members after a misunderstanding. Her brother’s son was struck and died instantly, and a bullet went through Ms. A’s shoulder. She was hospitalized in Kitgum District Hospital and recovered after several months. During her hospitalization, she did not receive any mental health evaluation or counseling. Her husband’s family blamed her for the arrest of her husband, her own family blamed her for the death of her nephew, and her children were taken away from her. After discharge from hospital, she returned to an empty home.

Ms. A was isolated from both family and friends. She felt shame, worthlessness, and uselessness and felt that she did not belong to her community anymore. She attempted suicide three times by trying to hang herself with a rope, but each time she was seen by someone who alerted others and intervened.

Community elders urged both families to perform a cleansing ritual called mato oput to remove the curse that had brought misfortune in her family and was responsible for her suicide attempts. A traditional healer was invited to conduct the ceremony. Both the conflicting families and community elders gathered around a tree called oput in the local language. The traditional healer crushed a portion of roots from the tree to make a solution, and the two parties were told to drink this solution from the same calabash as a sign of reconciliation and reunion.

Ms. A reports that this cleansing ritual did not resolve the conflict between the two families. She remained isolated; her husband's family refused to allow her to associate with her children. She felt helpless,with a lot of pain in her heart. She decided to leave her village, and she went to live in the town of Gulu, some 100 km away, with another relative. She tried to earn a living by doing odd jobs, but she lacked energy most of the time and tired easily. Consequently, she earned very little money and could not acquire the basic necessities to get by. She got involved in relationships with men, but none of these were successful. Domestic violence was cited as one of the reasons she left these relationships.

Ms. A reports experiencing multiple body pains and weakness, which she thought could be a sign of high blood pressure. When she visited the Gulu regional referral hospital, she agreed to HIV pretest counseling and later was diagnosed with HIV/AIDS. She was devastated by the diagnosis. She felt extremely sad, crying most of the day, and she felt weak, unable to do any work. She felt a lot of pain whenever people talked about her HIV status. Her HIV care providers started her on antiretroviral therapy and counseled her about adherence to medications, but she was never screened for depression. When her eldest son learned of her condition, he went to Gulu and brought her back home. She attended faith healing sessions led by a pastor in the village until a member of the village health team advised her to go for a mental health evaluation at the PCAF outreach center in Mucwini.

Discussion

Depression is the leading neuropsychiatric illness that contributes to the burden of disease in low- and middle-income countries (

1), and socially disadvantaged women are affected most by the illness (

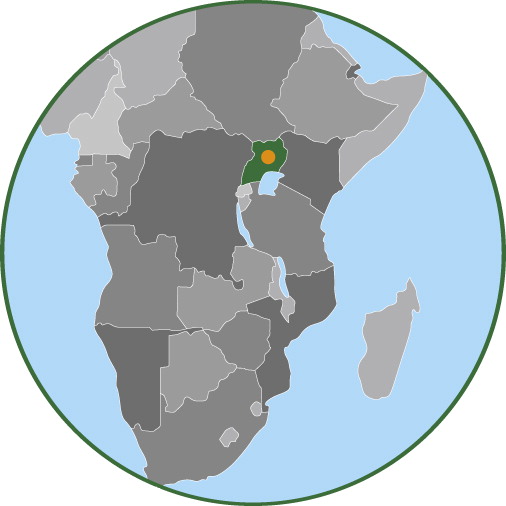

2). Depression is highly prevalent in primary care, with estimates ranging from 17% to 46% in Ugandan studies (

3–

6). War-related and gender-based violence, chronic diseases such as HIV/AIDS, and poverty and low education levels are some of the major determinants of the risk for depression worldwide (

7).

Although the World Health Organization recommends that mental health care be integrated into primary health care services (

8), research from many African countries indicates that implementation of this recommendation faces numerous challenges and has been minimal (

9–

11). Research has shown that providers of primary care services do not understand patients’ explanatory models of mental illness (

12). An increase in the mental health literacy of primary care health workers is a necessary first step in the early diagnosis and prompt management of depression in primary care.

Northern Uganda’s primary care infrastructure consists of a first-level health center (Health Center I), which is the first contact point for patients. This usually refers to members of the village health team, who conduct outreach activities under a tree or in a community building. The second level of care (Health Center II) offers only outpatient services. The third level (Health Center III) has a maternity unit and male and female wards, with a bed capacity of eight. At these three levels of primary care, there are no mental health workers to screen for and manage depression. The next level of health care (Health Center IV) usually has only one psychiatric nurse. The highest level of care is at the district hospital, where a psychiatric clinical officer and a few psychiatric nurses are employed (

13).

Although northern Uganda has been regarded as a postconflict region for the past 6 years, the adverse impact of the civil war (1987–2007) remains (

14). Individuals who survived the war have returned to their homes from the camps for internally displaced persons. They still face serious challenges, such as lack of basic livelihood skills and the resultant poverty, which itself is a well-documented risk factor for depression (

15). Consequently, the government has encouraged public-private partnerships, such as the one formed between the Peter C. Alderman Foundation (PCAF) and Ugandan government institutions to enhance mental health services and improve the quality of life and functioning of individuals in this postconflict region (

16).

The case of Ms. A is in keeping with evidence from several sub-Saharan African countries that testifies to four major findings: gender roles and gender discrimination play a big role in precipitating depression in women (

17,

18); gender-based violence, economic deprivation, and poor marital relationships have been identified as important risk factors for the occurrence and chronicity of depression (

18); individuals experiencing depressive symptoms, general health care workers, and traditional and faith healers are not aware that these are symptoms of a treatable illness (

19); and symptoms of poor mental health are frequently attributed to supernatural or spiritual causes (

20–

22). Each of these findings has important implications for global mental health policy and practice.

First, the level of gender-based violence in Ms. A’s life points to a need for interventions for depression that will provide a framework for addressing conflict-induced changes in gender roles, which undermine traditional family roles and spheres of authority. In postconflict areas, family violence is exacerbated by many factors, including the stress of displacement, lack of employment or activity for men, and challenges to the role of husband and father. The lack of structure to one’s daily routine often leads to increased consumption of alcohol or other drugs, which has a direct correlation with domestic violence (

23).

Second, the extreme poverty in Ms. A’s life may have played a role in perpetuating her depressive symptoms. Researchers have demonstrated a strong association between indicators of poverty and the prevalence and outcome of depression (

24). While the case report does not address mechanisms that underlie this relationship, other research has shown that this relationship is bidirectional (

24). Living in poverty not only increases the risk of developing a depressive illness but also is associated with worse depression outcomes (

24). It is of paramount importance that interventions for depression in low-resource settings such as postconflict northern Uganda target alleviation of poverty for both men and women. For example, in our work in the Kitgum PCAF clinics, we integrated training in basic livelihood skills into a locally developed low-intensity psychological intervention to treat depression in HIV-affected individuals (

25). The intervention had a remarkable impact on social and economic outcomes of both male and female participants, which suggests that this is a feasible strategy (

26). (In the online edition of this article, see a video describing the intervention.) Larger and randomized evaluations of such interventions are warranted.

Third, studies in sub-Saharan African countries have shown that symptoms of depression are not regarded as a mental health problem but rather a social problem resulting from poverty, alcoholism, poor marital relations, supernatural or spiritual attacks, or “thinking too much,” all of which, it is believed, traditional healers can treat effectively (

27). The belief that supernatural or spiritual causes are responsible for poor mental health is widespread in African countries. Recent studies in Uganda have shown that traditional healers use a variety of indigenous labels to describe what psychiatry categorizes as mental disorders (

20,

21).

Studies in African countries have demonstrated that when people need help, they will seek it wherever it can be found. A traditional healer is present in all villages, and the majority of individuals with mental illness will at some point consult the traditional healer, whether or not they have received biomedical services (

27). Indeed, Uganda’s Ministry of Health is advocating for the recognition and incorporation of the practice of traditional medicine in the country’s health care delivery (

20). However, research is needed on how traditional healers can be used to narrow the treatment gap for depression and other mental disorders in sub-Saharan Africa.

Lastly, HIV infection may have perpetuated and amplified Ms. A’s depressive symptoms. The experience of living with HIV infection is associated with multiple social, psychological, and biological stressors, which lead to excessive worries (

28,

29). Given the shortage of mental health workers, general health care providers need to be equipped with the skills to screen for and treat depression. Counseling opportunities could be used to screen individuals for depression and to initiate basic psychological interventions, such as psychoeducation to increase mental health literacy. Furthermore, active monitoring of depressive symptoms could be initiated during HIV care.

Education about how to recognize depressive symptoms, how depression can increase the risk for HIV infection and other sexually transmitted diseases, and the detrimental effects of violence against women should be important components of interventions targeting depression. Given the scarcity of qualified health care workers in remote villages such as the one where Ms. A lives (

30), such interventions can be made more accessible by training lay community workers living in these villages to deliver the interventions using the task-shift model (

31).