The habit hypothesis of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) suggests that the disorder reflects dysfunction in the brain systems that support automatic habits and more purposeful, goal-directed control over action (

1). Habits are automatic stimulus-driven behaviors that can arise under many conditions, the most commonly accepted of which is the overtraining of simple responses (

2). However, habits can also arise from failures in goal-directed control, which can render behavior habitual even very early on in training (

3,

4). Therefore, these two systems, habit and goal-directed, each contribute to the likelihood that a habit will be performed in a given situation. In OCD, it is currently unclear which of these putative systems drives the exaggerated tendency to display habits, which has been observed regardless of whether they work toward gaining reward (

5) or toward avoiding punishment (

6). However, two recent studies found deficits in goal-directed behavior during trial-by-trial learning in OCD, using paradigms that did not involve repeating simple responses (

7,

8). This suggests that excessive habits in OCD could arise as a result of disturbances in the goal-directed system, rather than the habit system. The present study aimed to test for neurobiological convergence in support of this possibility, drawing on a rich cross-species neuroscience literature, which has identified dissociable neural substrates of these two systems (

9).

The medial orbitofrontal cortex and the caudate nucleus each contribute to goal-directed control over our behavior. Specifically, the caudate and medial orbitofrontal cortex both have been shown to subserve learning involving action-outcome contingencies (

4,

10,

11). Additionally, the medial orbitofrontal cortex plays a pivotal role in tracking the current value of outcomes (

12–

14). Another region in the basal ganglia, the putamen, is necessary for the formation of stimulus-response habits with practice (

11,

15,

16). We tested whether functional activation in these three regions was associated with habit-forming biases in OCD, and in doing so we aimed to reveal whether dysfunction in the goal-directed or habit-learning system accounted for excessive habits in OCD.

Generally, the habit hypothesis of OCD exhibits good face validity in that both habits and compulsions continue in spite of awareness that these actions are not useful/wanted (i.e., ego-dystonic) and are associated with the experience of an urge to perform them (

6). A secondary goal of this study was to test the neurobiological validity of the OCD habit hypothesis by assessing whether activation associated with habit forming in OCD overlaps with activation implicated in the disorder's symptoms. The literature has broadly converged on a model of OCD that involves hyperactivity within fronto-striatal circuits (

17), with effects in the orbital gyri and caudate nucleus head being among the most reliable (

18–

20). Evidence for this model comes primarily from functional brain imaging studies examining brain activity at rest (

21–

23), during symptom provocation (

24–

26), and pre- and posttreatment with psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy (

22,

27–

29). A more widely distributed network of regions, including the nucleus accumbens, amygdala, and other parts of the prefrontal cortex (

30–

32), has also been implicated in OCD in studies employing task-related functional MRI (fMRI) analysis. However, given that fMRI activation patterns are entirely dependent on the task employed, results have been unsurprisingly heterogeneous and have not confirmed activation seen during earlier studies examining task independent activity patterns that are characteristic of OCD. We hypothesized that if excessive habits are an appropriate model of OCD, then brain activation associated with habit formation in OCD patients should overlap with activation associated with the symptoms, specifically in the medial orbitofrontal cortex and caudate. Although less consistently implicated, there is some suggestion that the putamen may be enlarged in OCD, an effect related to age and plausibly the chronic performance of compulsive behavior (

33). Therefore, we also tested the possibility that aberrant activation in the putamen, perhaps reflecting overactive habit learning, would be associated with habits in OCD.

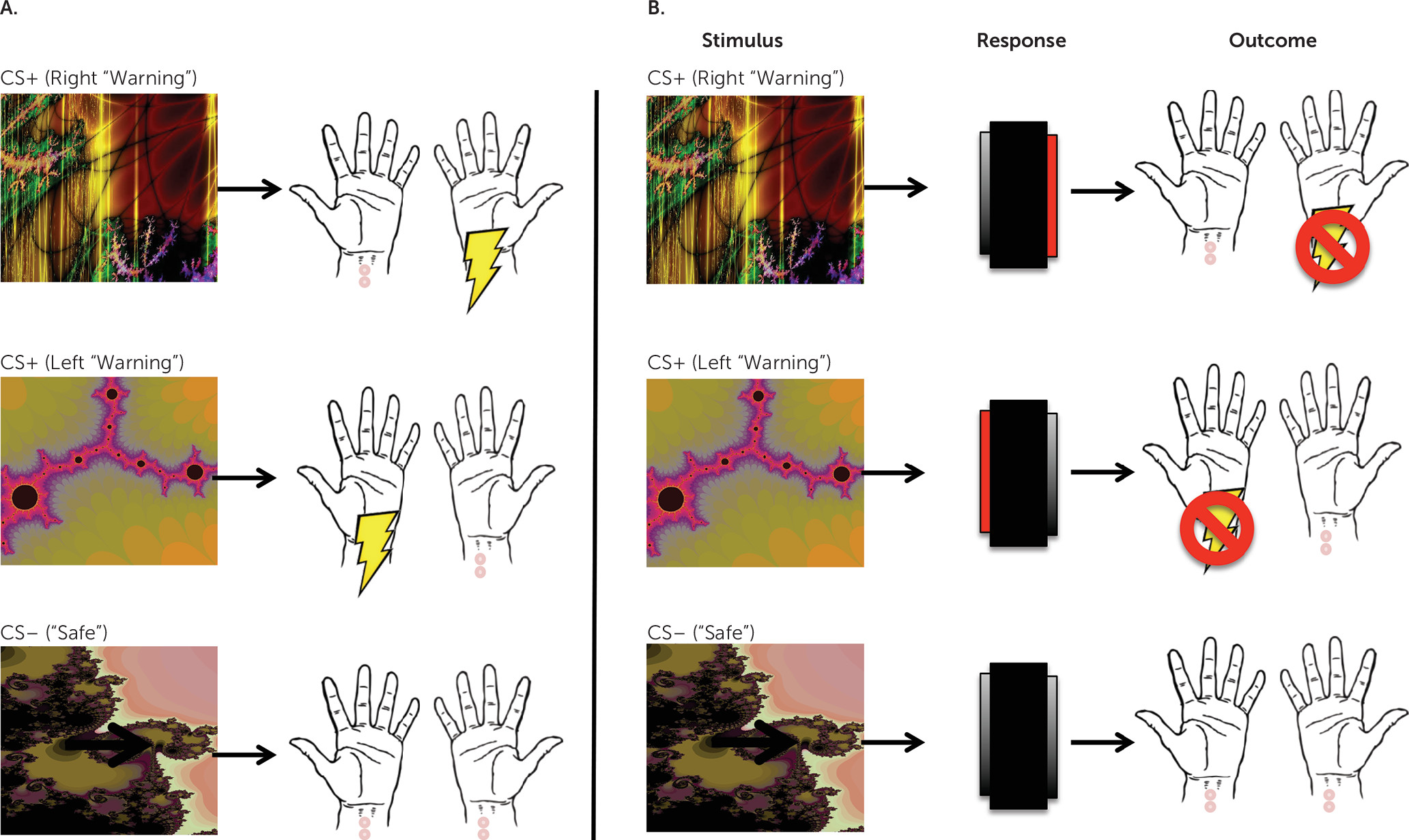

To investigate the neural basis of habit-forming biases in OCD, we used fMRI to examine changes in brain activation while patients acquired and later performed habits. To do this, we used an avoidance task that has previously been shown to be sensitive to differences in habit formation between OCD patients and comparison subjects (

6). Only individuals who had not previously participated in the previously published behavioral study using this task were eligible to enroll. This task was selected because avoidance rather than appetitive compulsions are characteristic of OCD. Therefore, this approach allowed us to model the disorder more closely and, secondarily, to investigate how habit learning might relate to anxiety and explicit fears in OCD. To test for habits, we used the “outcome devaluation” technique, in which behavior is defined as a habit if it persists despite changes in the value the action produces (

34); in other words, habits are behaviors that are driven by stimuli, not by motivation or goals.

Discussion

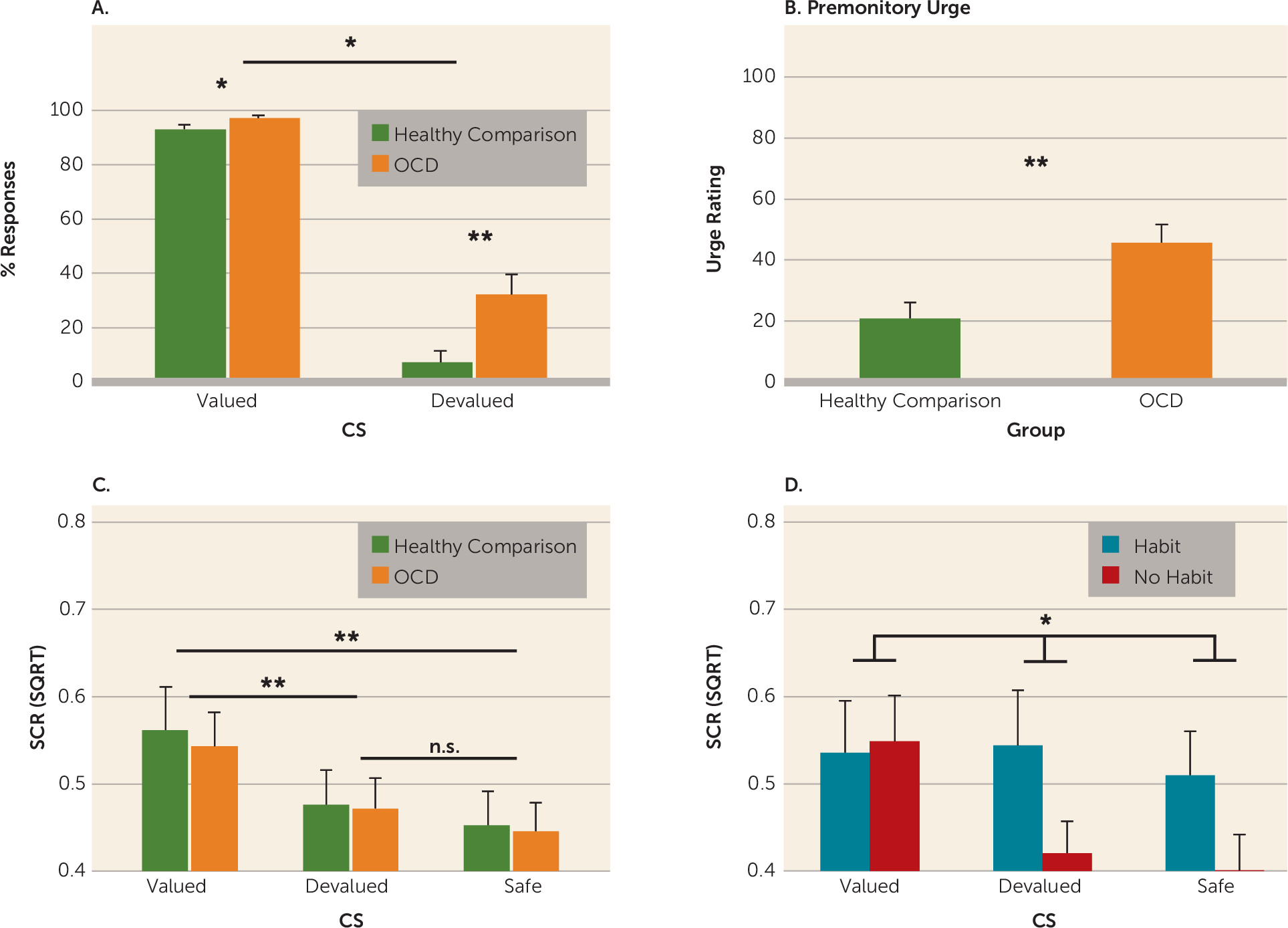

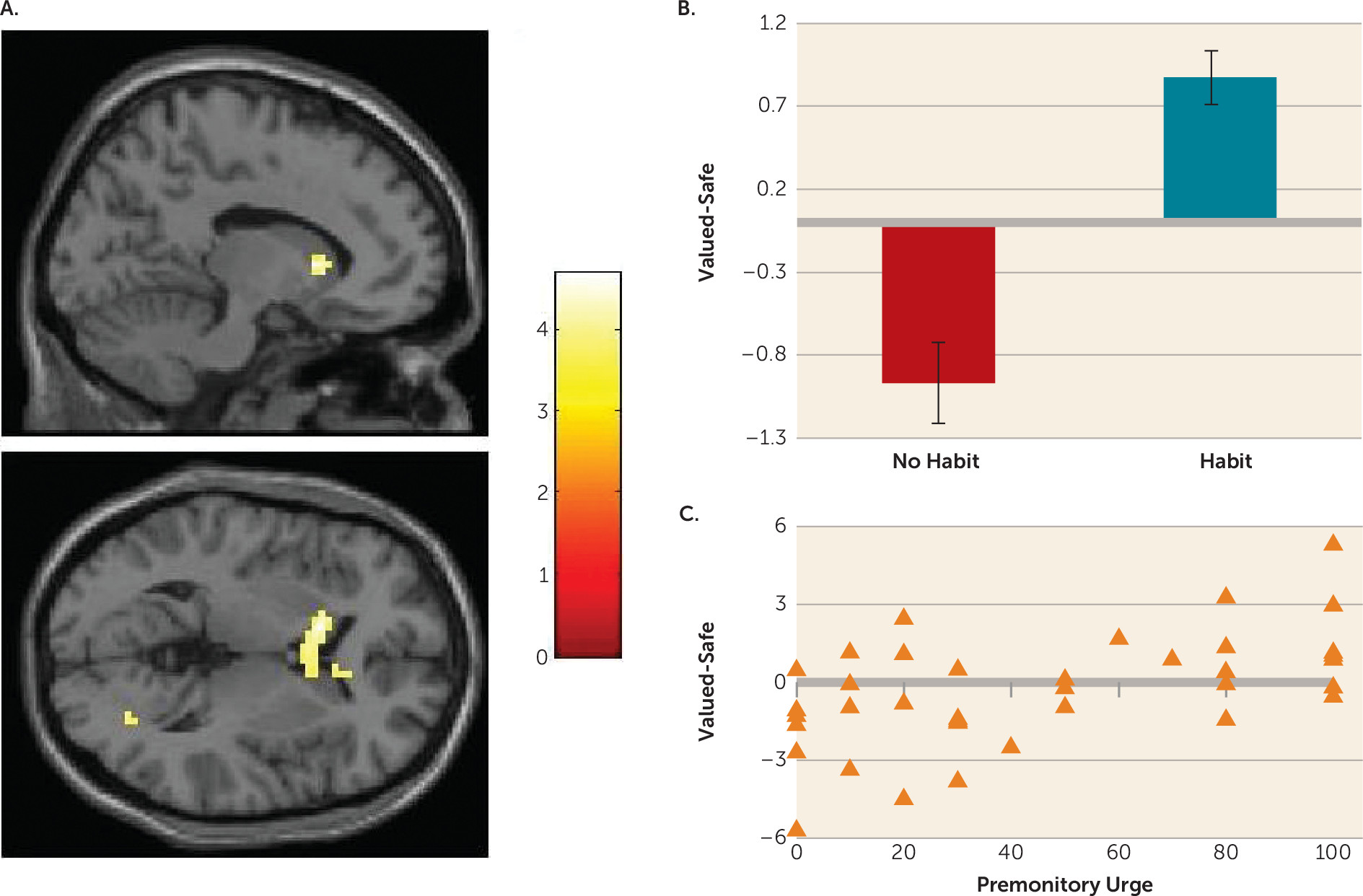

Habits in OCD were associated with hyperactivation in the caudate nucleus. Specifically, greater caudate activity was observed in patients whose actions had become habitual, compared with healthy comparison subjects and OCD patients who did not form habits. Independent analysis revealed that, across the entire OCD group, greater activation in this region was correlated with the self-reported urge to perform these habits; there was no such relationship in healthy comparison subjects.

Translational work in rodents and humans has previously revealed that the caudate is necessary for goal-directed control over action. Lesions to this region in rodents render behavior habitual after only moderate training (

4). Cocaine-induced habitual responding is associated with increased excitability in the rodent homolog of the caudate (

37), and in humans, white matter connectivity between the caudate and the medial orbitofrontal cortex is predictive of improved goal-directed control over action (

11) on a task that reveals habit biases in OCD (

5). Findings from studies examining dynamic mechanisms of associative learning (rather than devaluation) suggest an important role for the caudate in linking outcomes to actions (i.e., contingency learning [

10,

38,

39]). However, in the present study, since explicit contingency knowledge was matched across groups, we would not expect the direction of activity in our study to mirror these results. Rather, our results may reflect difficulties in translating explicit contingency knowledge into action preferences, similar to a recent study by Corbit et al. (

37). Hyperactivation in the caudate is one of the most consistent neurobiological markers of OCD symptoms (with medial orbitofrontal cortex hyperactivation being the other) (

18,

19), and our data therefore lend strong support to a model of OCD centered on deficits in goal-directed control over actions, resulting in compulsive habits.

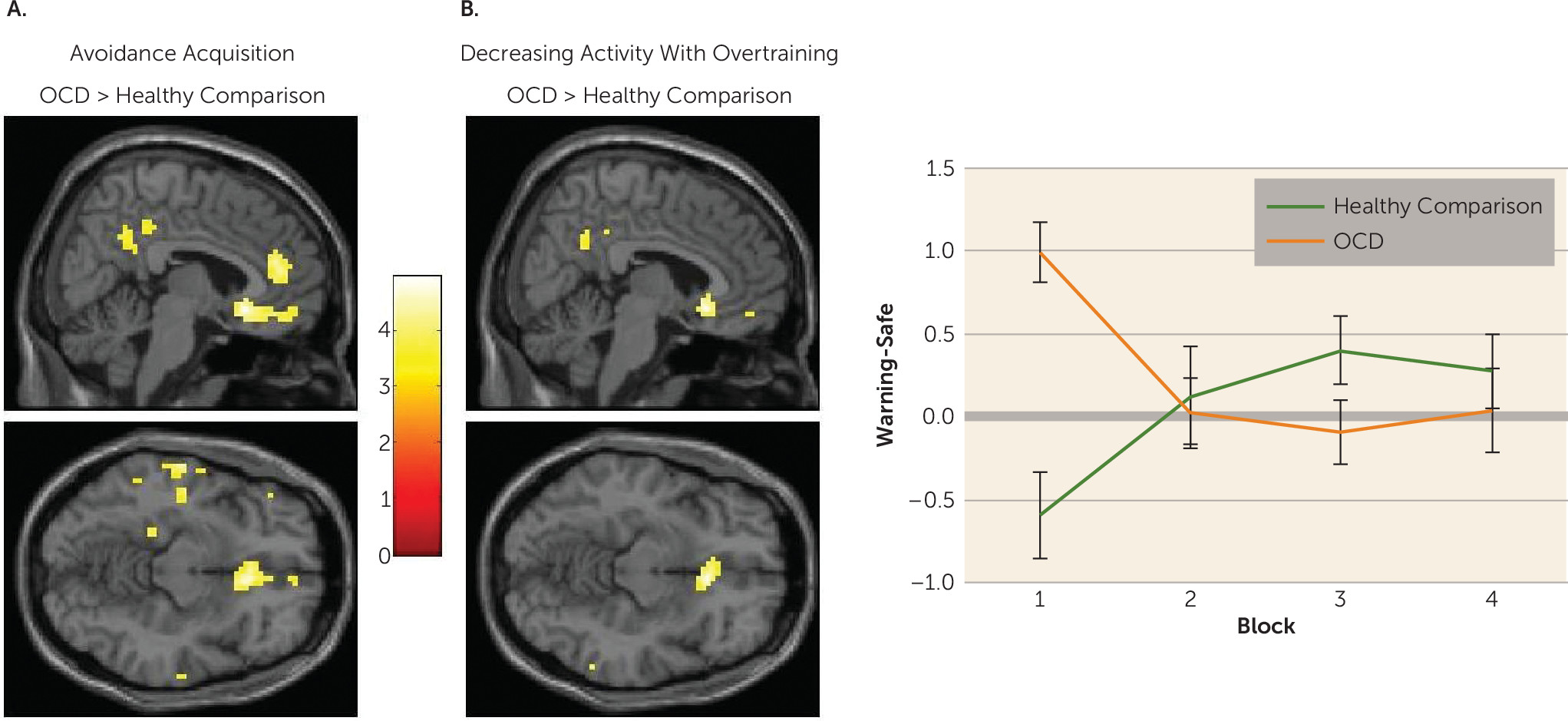

OCD patients showed initial hyperactivation in the medial orbitofrontal cortex during avoidance learning, which reduced with extended training; whereas healthy comparison subjects showed the opposite pattern. A post hoc psychophysiological interaction analysis revealed that during the acquisition of avoidance, positive coupling between the caudate and the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex (partially overlapping with the medial orbitofrontal cortex cluster) was observed in OCD patients who later demonstrated habits, but a negative coupling was observed in those who did not. The role of the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex in habit forming has been sparsely studied, but two studies have shown that its likely homolog, the infralimbic cortex, must be intact for habits to persist in rodents (

40,

41), suggesting that excessive connectivity between this region and the caudate may be one possible way that goal-directed control is compromised in OCD. Other differences in BOLD activity associated with habit formation within our OCD group were observed in the precuneus and superior occipital gyrus, which were sensitive to extended training, as well as functional connectivity between the caudate and the right inferior frontal gyrus and pallidum during early learning. These results require replication but suggest the possibility that a more distributed network may be involved in habit-forming biases in OCD.

Excessive habit formation in OCD was not related to differences in activation in the putamen. This region is critical for habit formation in rodents, such that lesions to the homologous dorsolateral striatum allow animals to remain goal-directed despite overtraining (

15). Moreover, a similar dependency has been observed in healthy humans, such that the formation of habits is associated with white matter connectivity strength between the putamen and premotor cortex (

11), as well as changes in putamen activity over time (

16) (although directionality of the latter association has been inconsistent and may not relate to cue-evoked responses but rather responses in general [

42–

44]). Although applying the usual caveat when interpreting null effects, the present data suggest that acquisition of automatic action tendencies may not be affected in OCD. Rather, habit biases in OCD appear to emerge as a result of deficits in goal-directed control associated with caudate (and possibly medial orbitofrontal cortex) hyperactivity. This conclusion dovetails with recent data showing that model-based instrumental learning, which is a constituent of goal-directed control, is impaired in OCD and reliant on the structural integrity of the medial orbitofrontal cortex and caudate but not the putamen (

8).

The present study investigated avoidance, rather than appetitive, habits in order to determine how conditioned and explicit fear relate to habit formation in OCD. Since this is the first study, to our knowledge, to examine the neural correlates of avoidance habits, whether these results can be generalized to appetitive habit forming, which is similarly overactive in OCD (

5), is an open question. The study of avoidance is critical in OCD; however, previous studies have shown that aberrant fear-conditioning processes are characteristic of OCD. For example, patients exhibit a pattern of hypoactivation in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (partially subsuming the medial orbitofrontal cortex) and caudate during fear conditioning (

45). The results of the present study converge with these previous findings in terms of localization but diverge with respect to directionality, a difference presumably associated with passive fear learning versus avoidance (

46).

While we observed no differences in skin conductance response between OCD patients and comparison subjects, OCD patients who formed habits did not show differential skin conductance responses to the stimuli (valued, devalued, and safe) during the habit test (for results, see the

data supplement). This could reflect overgeneralization of fear, which has been shown to relate to maladaptive instrumental avoidance (

47). However, because these patients were able to discriminate during learning, this effect is likely a consequence rather than a cause of habitual responding. Taken together with the findings of Milad et al. (

45), as well as with findings from studies suggesting that stress and anxiety contribute to habit biases in healthy people (

48,

49), it is likely that a complex interaction between fear learning and habits may be critical to understanding the pathogenesis of OCD.

The findings in the caudate pertain primarily to patients who have formed habits compared with those who have not, rather than representing a difference between OCD patients and healthy comparison subjects. As such, it is possible that with further training, for example, a similar pattern might be observed in control subjects who form habits. This is a question for future research. If this is the case, our results suggest that habit forming and associated caudate hyperactivity is hastened in OCD, rather than this process being qualitatively different.

The majority of our medicated patients were taking serotonergic medication (mainly SSRIs), which in previous work has been shown to affect avoidance responding and inhibition in healthy humans (

50). However, we found no evidence for differences between medicated and nonmedicated patients (matched for symptom severity) in terms of behavior and in almost all brain activation contrasts, indicating that medication effects did not drive our results.