On average, 10% of children and adolescents in the United States meet criteria for an anxiety disorder, which impairs their social, familial, and academic functioning (

1,

2). Etiological models of anxiety disorders implicate several family-based risk factors (

3). Family aggregation studies indicate that children of anxious parents have an elevated risk of having an anxiety disorder (

4), and specific parenting practices, such as modeling of anxiety and overcontrol/overprotection, contribute to elevated anxiety (

5). Family-based treatments for pediatric anxiety disorders that target these parenting practices, along with other cognitive-behavioral strategies, have been found to reduce child anxiety (

6–

8).

In light of the high prevalence, associated impairment, and familial nature of pediatric anxiety disorders, family-based prevention targeting high-risk offspring holds promise for reducing the incidence and burden of these illnesses. To date, anxiety prevention programs have been only modestly successful, and most have been conducted in schools (i.e., a universal prevention approach) (

9,

10). Meta-analyses of anxiety prevention programs have reported modest effect sizes (an average Cohen’s d of 0.18 and Hedges’ g of 0.22) at postintervention assessment, and no program in the United States has targeted high-risk offspring of anxious parents for prevention (

9,

10).

We sought to address this gap by evaluating the efficacy of a family-based intervention (the Coping and Promoting Strength program) for high-risk offspring. The intervention was grounded in cognitive-behavioral strategies for pediatric anxious youths (

11) and Beardsley’s prevention program for offspring of depressed parents (

12). In a pilot test using a small sample (N=40), the intervention showed positive effects over a 1-year period (

13). The present study is a replication with a sufficiently large sample to test the efficacy of the Coping and Promoting Strength intervention. The primary study aim was to assess the efficacy of the intervention relative to an information-monitoring control group in reducing the incidence of anxiety disorders and the severity of anxiety symptoms in offspring of anxious parents over 1 year. The effects of selected theory-driven parent and child mediators (global parental psychopathology, parental anxiety severity, parental modeling of anxiety, and child maladaptive cognitions) and moderators (child age, child gender, parent gender, parent comorbidity, parent-child gender match, and baseline child and parent anxiety level) were also examined.

Results

Baseline Characteristics and Group Comparisons

Table 1 summarizes participants’ baseline clinical and demographic characteristics. The two groups did not differ significantly on child demographic variables or on levels of child or parent anxiety. Mean parental age was higher in the information-monitoring group. There were also group differences in the attrition rate, with significantly more children in the intervention condition failing to complete the 1-year assessment within the allotted window (p=0.03; see the CONSORT diagram in the online

data supplement). Attrition analysis comparing families that remained in the study and families that dropped out indicated that parents who dropped out were significantly younger on average (mean age, 41.3 years compared with 37.2 years; p=0.002). Attrition analyses for group-by-attrition interaction were not performed because of the small attrition rate (N=4) in the information-monitoring group. One outlier, in the information-monitoring group, was identified on the clinical severity rating of the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule at the 6-month follow-up (outlier score, 35, compared with scores ≤18 for all others). For analyses involved with this variable, the results were consistent between the models with and without the outlier. We present the more conservative results without the outlier in the model.

Intervention Attendance and Adherence

Among the families in the Coping and Promoting Strength intervention group, the average number of sessions attended was 6.63 out of eight (range, 0–8) and 1.2 out of three booster sessions (range, 0–3); the total mean number of sessions attended was 9.01 out of 11 (SD=2.63, range, 0–11). The participating anxious parent attended all sessions and was accompanied by the other parent in a mean of 4.07 of the eight sessions (range, 0–8). Intervention adherence was assessed on 25% of each family’s recorded sessions by independent evaluators. Each evaluator rated adherence to specific session objectives (e.g., explaining the intervention model of anxiety reduction, teaching relaxation or cognitive restructuring techniques). The average adherence ratings per family ranged from 86.36% to 100%, and the mean adherence rating across all sessions was 97.58% (SD= 3.51), reflecting high levels of clinician adherence. Total number of sessions attended was unrelated to child outcomes.

Test of Independent Evaluator Blindness

At the postintervention and follow-up assessments, the independent evaluators were asked to guess group assignment. Kappa values for agreement between actual assignment and guessed assignment were 0.32, −0.08, and 0.03 at the three assessments, respectively. The independent evaluators seemed to be more aware of the group condition at the postintervention assessment than at the 6-month and 12-month follow-up assessments.

Onset of Child Anxiety Disorder

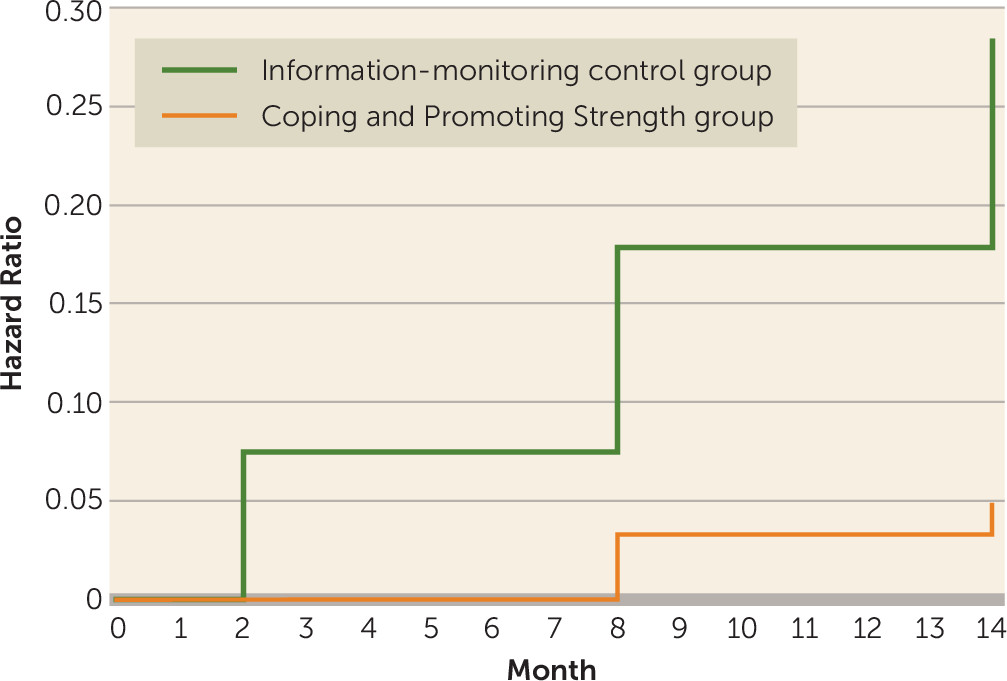

Table 2 lists the numbers of children in each group who developed an anxiety disorder over the course of the 1-year study. Cumulatively, three children in the intervention group (5.26%) and 19 children in the control group (30.65%) developed an anxiety disorder (odds ratio=8.54, 95% CI=2.27, 32.06; number needed to treat=3.9). The results of the survival analysis indicated that the rate of onset of anxiety disorders for children in the control group was 6.6 times higher than that for children in intervention group during the 1-year period (hazard ratio=6.60, 95% CI=2.00, 21.82; p=0.002).

Figure 1 illustrates the hazard functions for the two groups.

Changes in Anxiety Symptom Severity

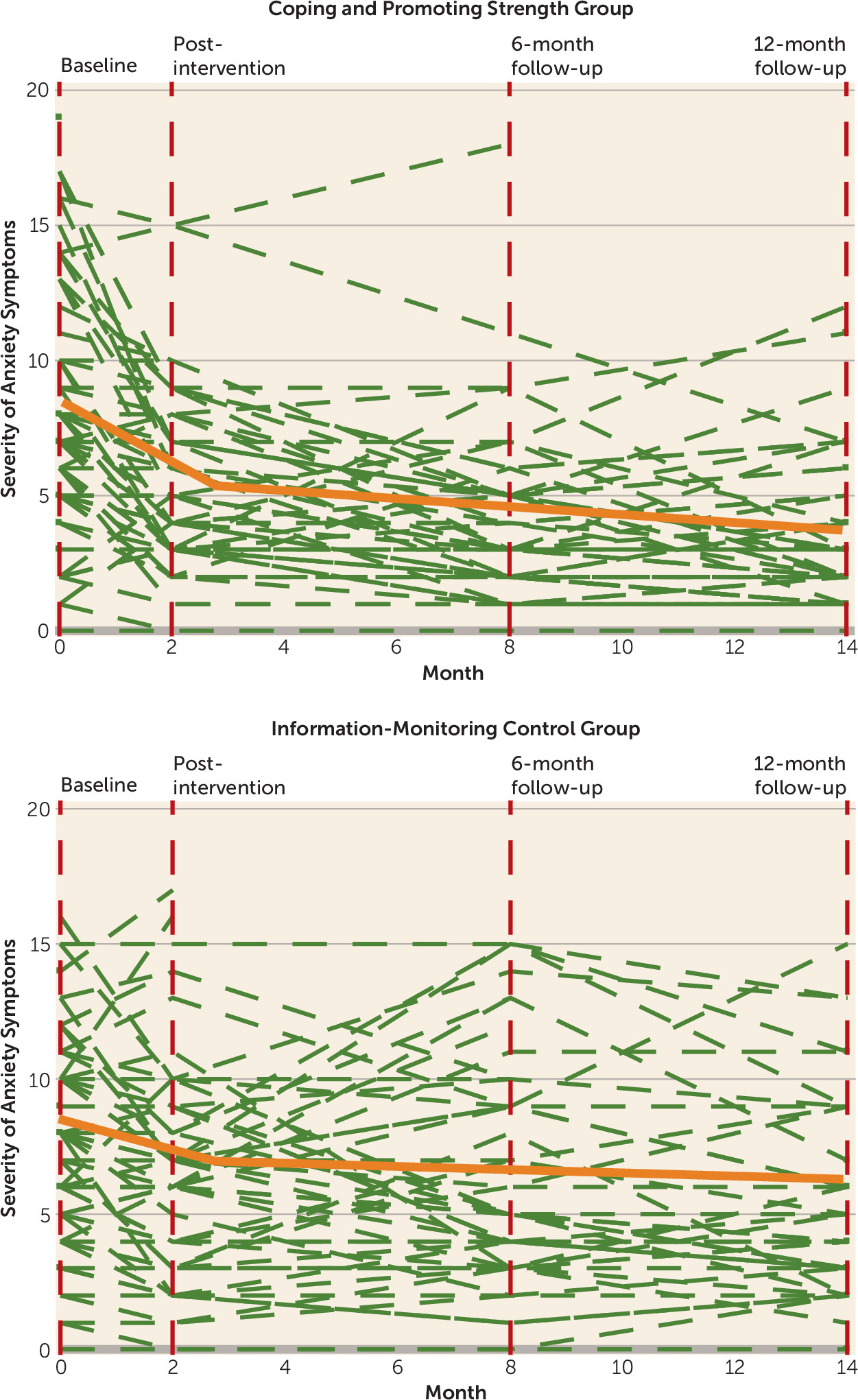

Table 3 shows the results of ANCOVAs for comparisons between the intervention and control groups on severity of anxiety symptoms at each of the postrandomization assessments. On average, youths who received the Coping and Promoting Strength intervention had significantly lower symptom scores at the postintervention assessment, as well as the 6- and 12-month follow-up assessments, compared with the control group.

Figure 2 illustrates the piecewise growth models for the intervention and control groups. Results of the multigroup comparisons of the growth factors on anxiety symptoms (i.e., the intercept, changes at the postintervention assessment, and linear growth after the postintervention assessment) showed that although both groups improved from baseline to end of intervention, the scores were reduced significantly more in the intervention group (B=−5.23, SE=0.82, p<0.01) compared with the control group (B=−2.21, SE=0.63, p<0.01) (difference=−3.02, 95% CI=−5.04, −1.00]). From the postintervention assessment to the 12-month follow-up, additional significant reductions occurred for the intervention group (B=−0.43, SE=0.13, p<0.01) but not for the control group.

Moderators and Mediators

The intervention effects were moderated by baseline child anxiety symptoms but not by any of the other moderators examined (child age and gender; parent gender, anxiety, comorbidity; parent-child gender match). Probing of the intervention effect at one standard deviation above and below the mean of baseline child anxiety symptoms (

27) indicated that the benefit of the intervention was stronger for children with higher baseline anxiety symptoms than for those with lower baseline anxiety symptoms (see

Table 3).

Mediation analyses revealed that significant reductions in both parental modeling of anxiety and parental global distress (but not anxiety alone) at the postintervention and 6-month follow-up assessments significantly mediated the intervention effects on outcomes for severity of child anxiety symptoms at the 1-year follow-up (mediation effect—where ab refers to the product of the unstandardized betas, a=regression path for intervention → mediator, and b=regression path for mediator → anxiety—through postintervention assessment anxiety modeling: ab=0.392, 95% CI=0.113, 0.642; through 6-month assessment anxiety modeling: ab=0.423, 95% CI=0.106, 0.725; through postintervention assessment parental distress modeling: ab=0.233, 95% CI=0.014, 0.488; through 6-month assessment parental distress modeling: ab=0.337, 90% CI=0.018, 0.713). Changes in child maladaptive cognitions did not mediate the intervention effects on outcomes.

Service Utilization

Parent reports of the use of mental health services for anxiety (yes/no) indicated that 21.5% of the control families, compared with 13.2% of the intervention families, reported receiving mental health services for their child’s anxiety over the course of the study (not a statistically significant difference).

Discussion

The study demonstrated that the Coping and Promoting Strength program, a brief family-based cognitive-behavioral intervention, reduced the incidence of anxiety disorders and the severity of anxiety symptoms over a 1-year period in offspring of anxious parents, a population at high risk for developing anxiety disorders. The onset of anxiety disorders over 12 months among high-risk children in the information-monitoring control group was nearly seven times higher than among those who received the intervention. The number needed to treat was 3.9. In addition to a lower rate of onset of anxiety disorders, the intervention group also exhibited lower severity of anxiety symptoms than the control group at each postbaseline assessment point, with medium to large effect sizes. Of particular note, while the largest reduction in anxiety symptoms was observed immediately after the intervention, reductions in anxiety symptoms were sustained for youths who received the intervention.

These findings are consistent with our pilot study results (

13), and this selective intervention fared better than universal anxiety prevention programs, which have shown average effect sizes of 0.18–0.22 (

9,

10). The present findings also parallel outcomes of interventions aimed at preventing the onset of depression in the offspring of adults with depression. Compas et al. (

28) reported a 1-year incidence rate of 20.8% for depression in an information-monitoring condition and 8.9% in a family intervention group.

It is notable that 31% of the control group developed an anxiety disorder within 12 months. This finding also replicates our pilot study data (

13), underscores the vulnerability of offspring of anxious parents, and is of considerable concern from a public health perspective. Given the adverse academic, social, and economic impact of anxiety disorders and the fact that many anxious youths never receive treatment (

29), additional resources are needed to identify and implement preventive or early intervention programs for at-risk youths in settings in the health care system that are practical and accessible for youths and families (e.g., primary care).

With respect to the moderators examined, the intervention had a similar effect for girls and boys as well as for younger compared with older youths, although the majority of youths fell into a narrow age range (7–12 years old). In contrast, among youths who received the intervention, those with high baseline anxiety symptom severity levels showed greater reductions in severity than those with low baseline levels, which suggests that the intervention is particularly helpful for youths with elevated anxiety symptoms. This is consistent with data from other prevention trials for anxiety (

30) and likely reflects the “room for improvement” that these youths exhibit. It may also be that youths with higher levels of baseline anxiety utilized the skills learned in the intervention more than their less anxious counterparts and thus benefited more from the intervention. Consistent with anxiety treatment trials (

31), parental trait anxiety level was not found to moderate outcomes, perhaps because trait anxiety does not adequately capture distress or impairment associated with parental anxiety or because the parents’ anxiety was effectively treated (63%−67% of anxious parents were in treatment). Additional parental moderators deserve examination in future studies.

An examination of several theory-driven intervention mediators revealed that the program reduced parental modeling of anxiety, which was directly targeted in the intervention, and that reductions in both modeling of anxiety and global parental distress (which included but was not limited to anxiety symptoms) led to lower levels of child anxiety symptoms. This finding clarifies potential mechanisms of the intervention’s impact and suggests that targeting specific parenting behaviors (such as reducing anxious modeling) and lowering parents’ overall distress levels (not anxiety specifically) were critical in reducing child anxiety symptoms. This is consistent with data from family-based treatment studies of anxious youths, which suggest that including parents in treatment leads to positive outcomes (

32). In contrast, child maladaptive cognitions, which have been found to be elevated in youths with anxiety disorders and to be a mediator of treatment response in clinically anxious youths (

33), were not affected by the intervention, and reductions in these cognitions did not explain the interventions’ effects at the 1-year follow-up. It is possible that maladaptive cognitions among youths without an anxiety disorder are not as salient as they are for clinically anxious youths or that other child risk factors, such as attention bias or behavioral avoidance, may be more important. Future analyses will examine additional mediators and whether the intervention had a greater impact on specific domains of anxiety.

A critical question for prevention programs is whether they have a net positive balance of economic costs and benefits. While our study was not designed to directly assess this question, we observed a higher rate of mental health service utilization among participants in the control condition, although it was not statistically different from the rate in the intervention group. The absence of a stronger divergence in mental health service use between groups is consistent with data showing that the majority of anxious youths do not seek or receive treatment (

29). Alternatively, the intervention may not have had an impact on treatment-seeking behavior or mental health service utilization. A longer follow-up of youths as they enter into the peak age of psychiatric illness onset would shed light on this issue.

Limitations

The study had several limitations. Our sample was made up of volunteers from predominantly Caucasian, two-parent families with relatively high incomes, and the findings may not generalize to nonvolunteers or to a more racially or economically diverse population. It is also possible that the parents in this sample were less severely ill than many parents with anxiety disorders, as they had few comorbid diagnoses and had greater resources to support their engagement in prevention. A majority of the parents had a primary diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder, which may reflect the excessive worry about their child’s well-being that is characteristic of this disorder (in contrast to social anxiety and avoidance, which may have reduced the likelihood of these parents enrolling). The children in this study may also not be representative of the population of high-risk offspring both because youths were excluded if they already had an anxiety disorder or any other psychiatric condition that required immediate treatment.

Another limitation is that the information-monitoring condition did not control for therapist time and attention. Thus, whether this intervention is superior to another active prevention program is unknown. Moreover, we did not conduct an evaluation of whether specific intervention components (e.g., relaxation, problem solving) were uniquely responsible for the beneficial outcomes. The completion rate for study evaluations was higher in the control group than in the intervention group, a finding that may be attributed to the offer of receiving the intervention after the 1-year assessment. We did not examine an exhaustive list of potential moderators and mediators, the sample size for specific moderation effects was small, and analyses were likely to be underpowered to detect these effects. Finally, the length of the follow-up was limited to 12 months; a longer follow-up is needed to further assess mental health outcomes and the balance of costs and benefits.