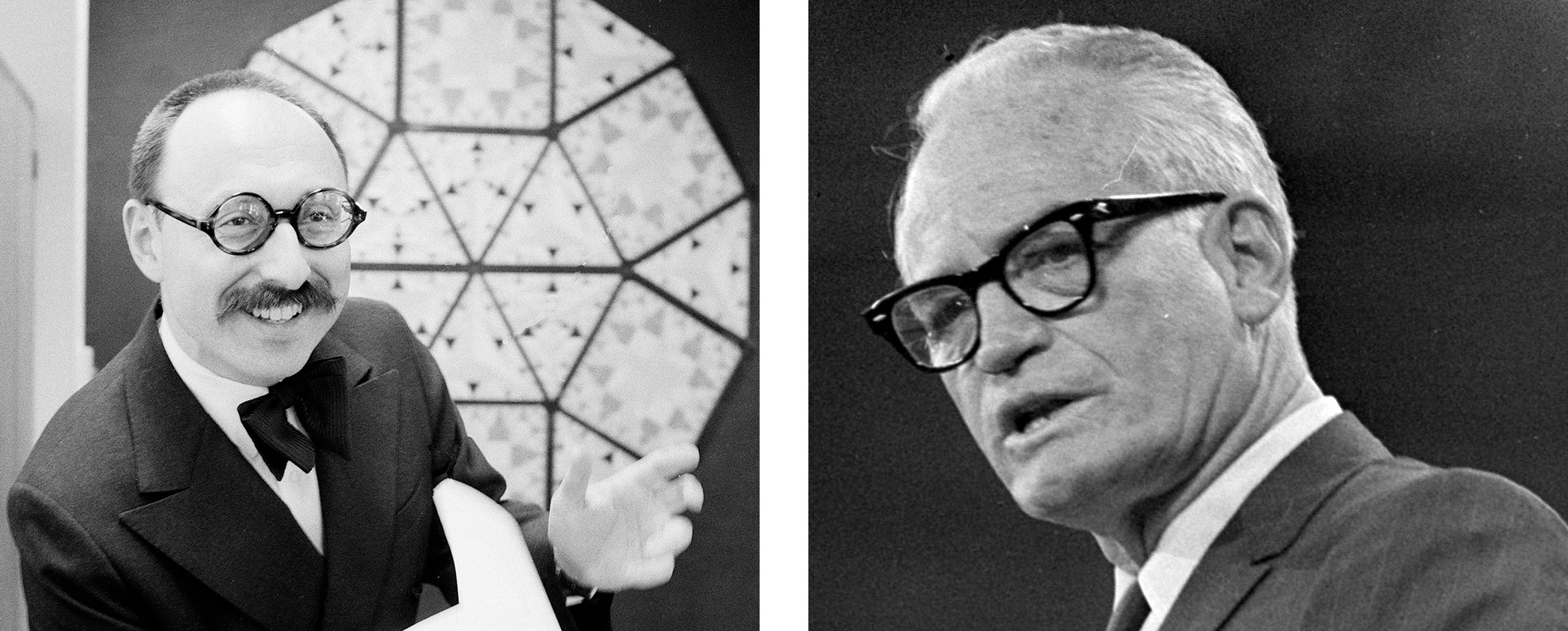

In 1966 former presidential candidate Barry Goldwater filed a libel suit (

1) in U.S. District Court against Ralph Ginzburg, publisher of the hip partisan magazine

Fact (“not for squares”). In 1964 Ginzburg had created a “poll” about Goldwater’s mental state and mailed it to 12,356 psychiatrists; over 1,800 responded. Some protested that the request was unethical, but many described Goldwater as having a personality disorder or a psychosis; a few said he was trying to prove his “manliness.” Predictably, Ginzburg trumpeted his conclusion that Goldwater was paranoid, unfit, and perhaps troubled by “intense anxiety about his manhood” (

2). Goldwater met the standard of “actual malice” and won a $75,000 judgment that withstood an appeal to the Supreme Court (

1).

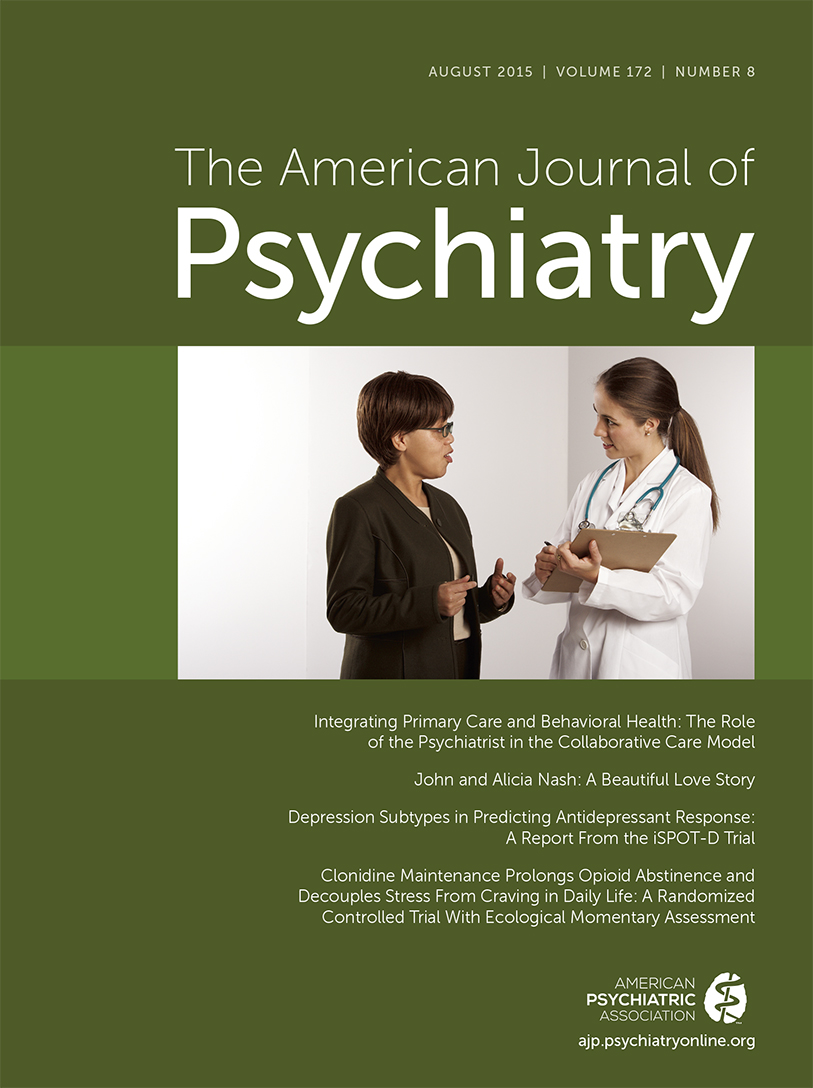

The case was an embarrassment to the American Psychiatric Association. Medical director Walter Barton sent a protest to

Fact, stressing that a psychiatrist’s evaluation must take place in the context of a doctor-patient relationship and a “thorough clinical examination” (

3). Ginzburg published anyway. In 1973 APA created a new ethical standard prohibiting psychiatrists from offering a diagnosis (later widened to include any professional opinion) without conducting an interview and obtaining consent (

4).

There has been much controversy over the rule. At times since 1973, psychiatrists have commented on public figures, leading APA to issue pointed reminders (

5). Former CIA profiler Jerrold Post has noted that ethical principles can conflict (e.g., public service and education versus respect for a public figure); he asserts that at times a “duty to warn” overrides other considerations (

6). In 1990 Post presented a public profile of Saddam Hussein, in the belief that misunderstandings of Hussein’s psychology were guiding policy and could lead to loss of life if not corrected (

7). Thus, “it would have been unethical to have withheld this assessment” (

6). Post says that APA viewed his work as ethical (

6), but no exceptions were ever incorporated into the rule’s wording. In 2008, in response to a query by Post (who reported on these events in a videotaped contribution to a forum I chaired at the 2015 APA annual meeting), the APA Ethics Committee issued an opinion on profiling of “historical figures” that is included in

The Opinions of the Ethics Committee on The Principles of Medical Ethics With Annotations Especially Applicable to Psychiatry [

8]. The Ethics Committee said such profiling is ethical if done to “enhance public and governmental understanding,” if no clinical diagnosis is given, and if it occurs in a peer-reviewed scholarly context, but the opinion does not define “historical figure” or explain the reasoning used. (Of note, Ethics Committee opinions do not have the same status as official APA positions.)

Little is known about the public figure’s point of view. However, parts of Goldwater’s deposition have recently been published. Goldwater testified that he was “extremely upset” by the

Fact article. Walking down the street and seeing people smile was now a different experience: “I don’t know if they are smiling out of respect for me or friendliness or whether they are thinking there goes that queer or there goes that homosexual…that man who is afraid of his masculinity.” In an era when homosexuality was officially a mental disorder, Goldwater said he hoped to spare “decent people” from having to face such accusations (

9). In a 2014 videotaped interview conducted for the 2015 APA annual meeting forum (“Ethical Perspectives on the Psychiatric Evaluation of Public Figures”), 1988 presidential candidate Michael Dukakis strongly supported the current rule.

Almost 50 years after

Goldwater v. Ginzburg, psychiatry continues to grapple with this case and its legacy (

10).

Acknowledgments

Photographs used by permission of the Associated Press.