We will examine the findings of our meta-analysis in the wider context of the role of psychotherapy in the treatment of depression. CBT and interpersonal psychotherapy have demonstrated efficacy in treating major depressive disorder, to a degree that is similar to that provided by antidepressant drug treatment (

36). There are also indications for the usefulness of psychodynamic psychotherapy, problem solving, marital and family therapy, and group therapy, even though the data that derive from randomized controlled trials are less compelling (

36).

The average depressed patient appears to express stronger preferences for psychotherapy than for antidepressant medications (

37), a finding that is of considerable clinical importance given that treatment preference is a potent moderator of response to therapy (

38). Patients receiving their preferred treatment (whether pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy) respond significantly better than those who do not receive their preferred therapy (

39). Understanding the most suitable applications of psychotherapy in the setting of a major depressive disorder and attempting to reach a shared decision with the patient thus represent crucial clinical issues.

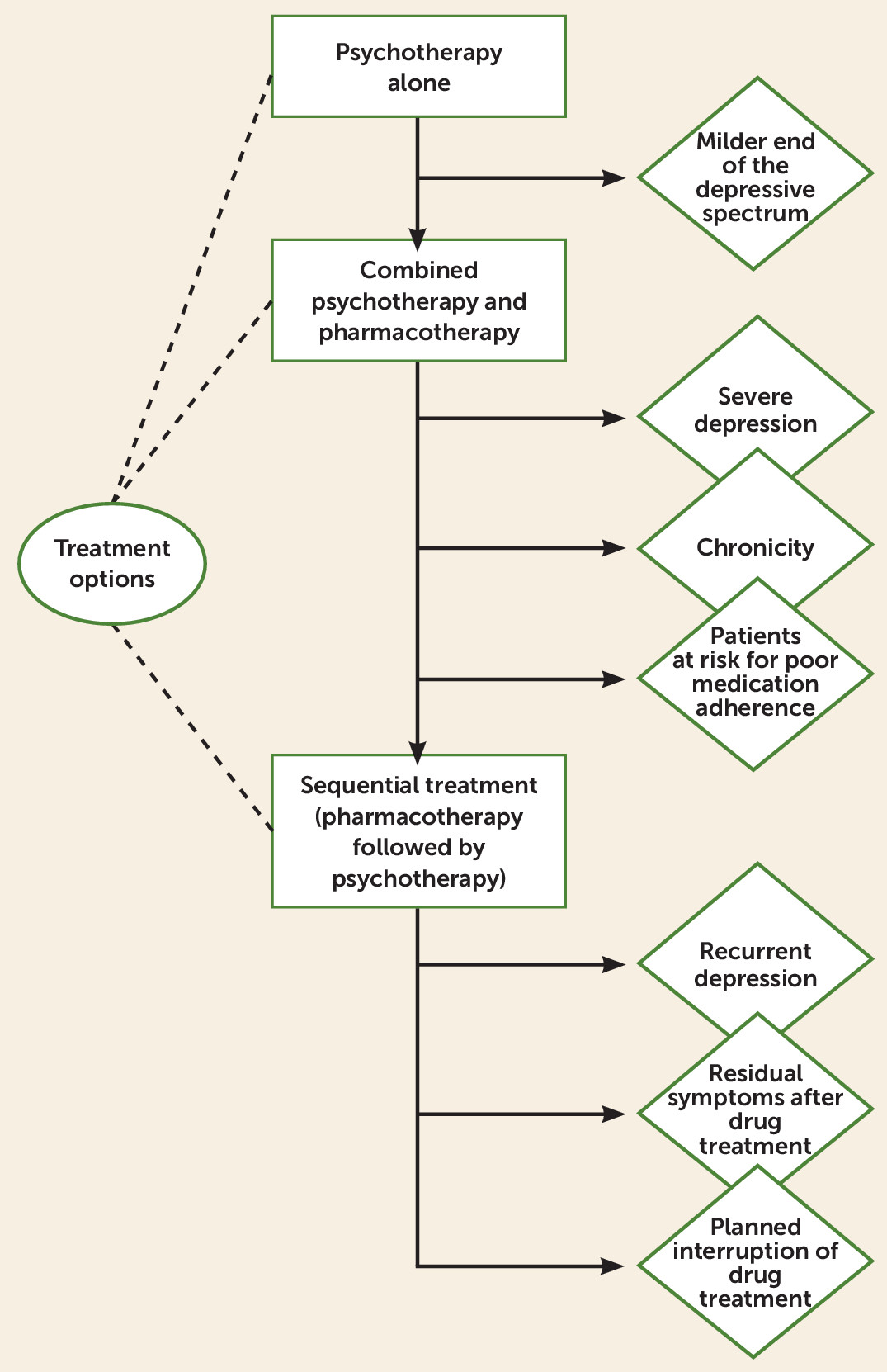

Selection of treatment according to evidence-based medicine relies primarily on randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses. However, this evidence applies to the “average” patient and ignores the fact that customary clinical taxonomy does not include patterns of symptoms, severity of illness, effects of comorbid conditions, timing of phenomena, rate of progression of illness, responses to previous treatments, and other clinical distinctions that demarcate major prognostic and therapeutic differences among patients who otherwise seem to be deceptively similar since they share the same diagnosis (

40). We will thus not simply compare treatment options for the average patient, but according to the clinical characteristics that each individual case may present with (

Figure 3). Both pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy entail advantages and disadvantages that should be weighed by clinical judgment (

40). We will not discuss the role of psychotherapy in patients who were found to be refractory to other treatments (

6).

Simultaneously Combined Treatment

The joint use of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in depression was found to yield short-term advantages compared with antidepressant drug treatment alone (

49) or psychotherapy alone (

50). More limited benefits were reported in terms of relapse prevention (

9–

13). In a recent meta-analysis (

51), the effectiveness of psychological interventions in preventing recurrences was enhanced when a sequential design was used.

Like antidepressants, psychotherapy also appears to entail side effects, as demonstrated in a recent review by Forand et al. (

52), and requires additional costs that need to be justified. The joint use of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy does not necessarily yield a superior effect: meta-analyses display a mixture of outcomes, and large additive effects tend to occur only in particular subgroups (

9–

13,

50–

52). High severity of depression and chronicity appear to be two important clinical characteristics that predict positive response to combined treatment (

44,

49,

50). Hollon et al. (

53), however, in a large and accurately designed study, found advantages of the addition of cognitive therapy to pharmacotherapy over drug treatment alone only with regard to severity. As Thase (

54) pointed out, the cognitive therapy model is conventionally time-limited and may not be suitable for conditions that require long-term treatments. The advantages of a psychotherapeutic strategy specifically developed for chronic depression—cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy—in yielding remission were demonstrated in two large trials (

55,

56).

Simultaneous use of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy was found to yield lower drop-out rates than monotherapy (

49) and may suggest its use in patients who are at risk for poor medication adherence. Interpersonal psychotherapy added to pharmacotherapy has been found to be better than medication alone in maintenance treatment (

57), and this can be an additional indication for combined therapy.

Sequential Treatment

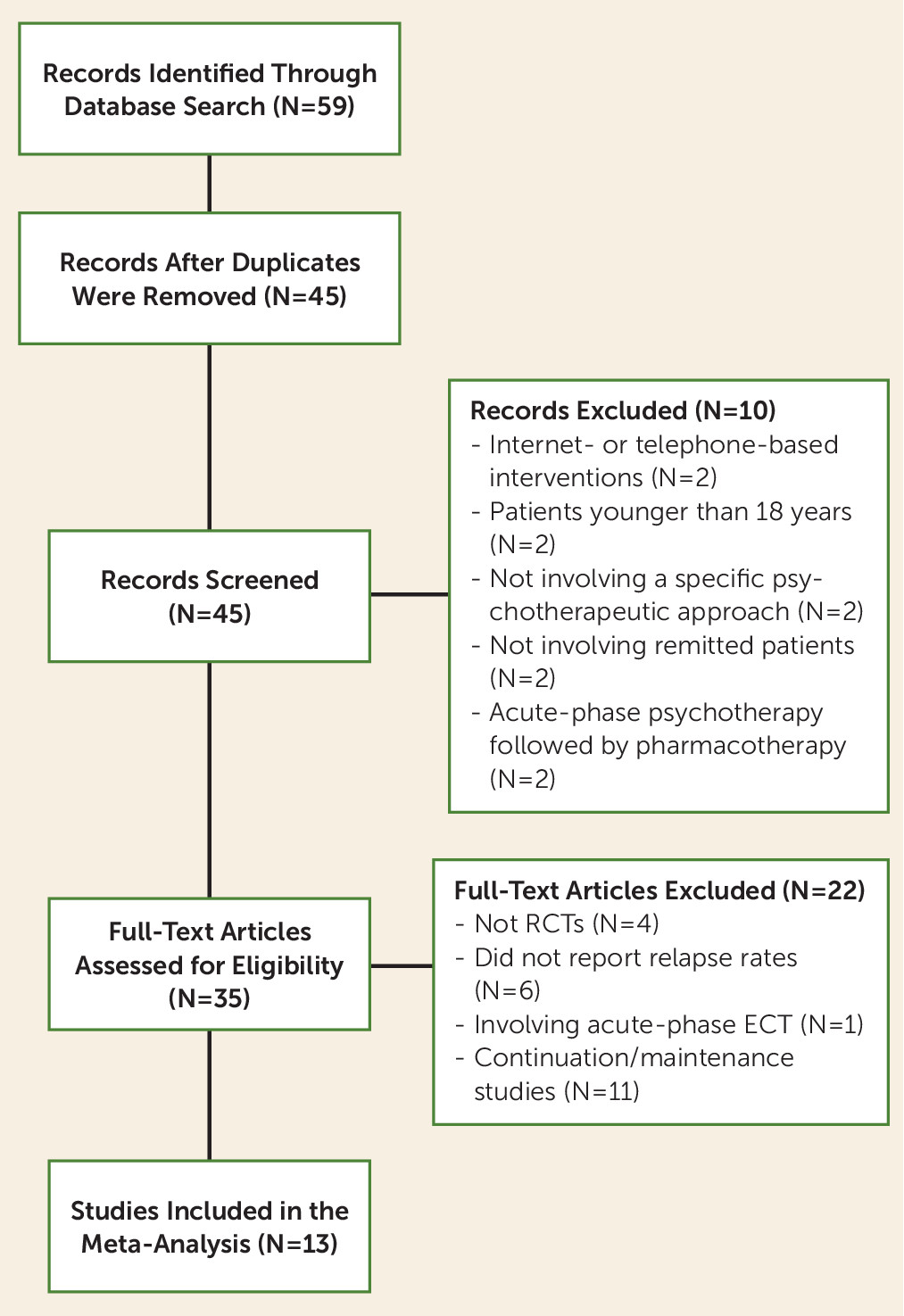

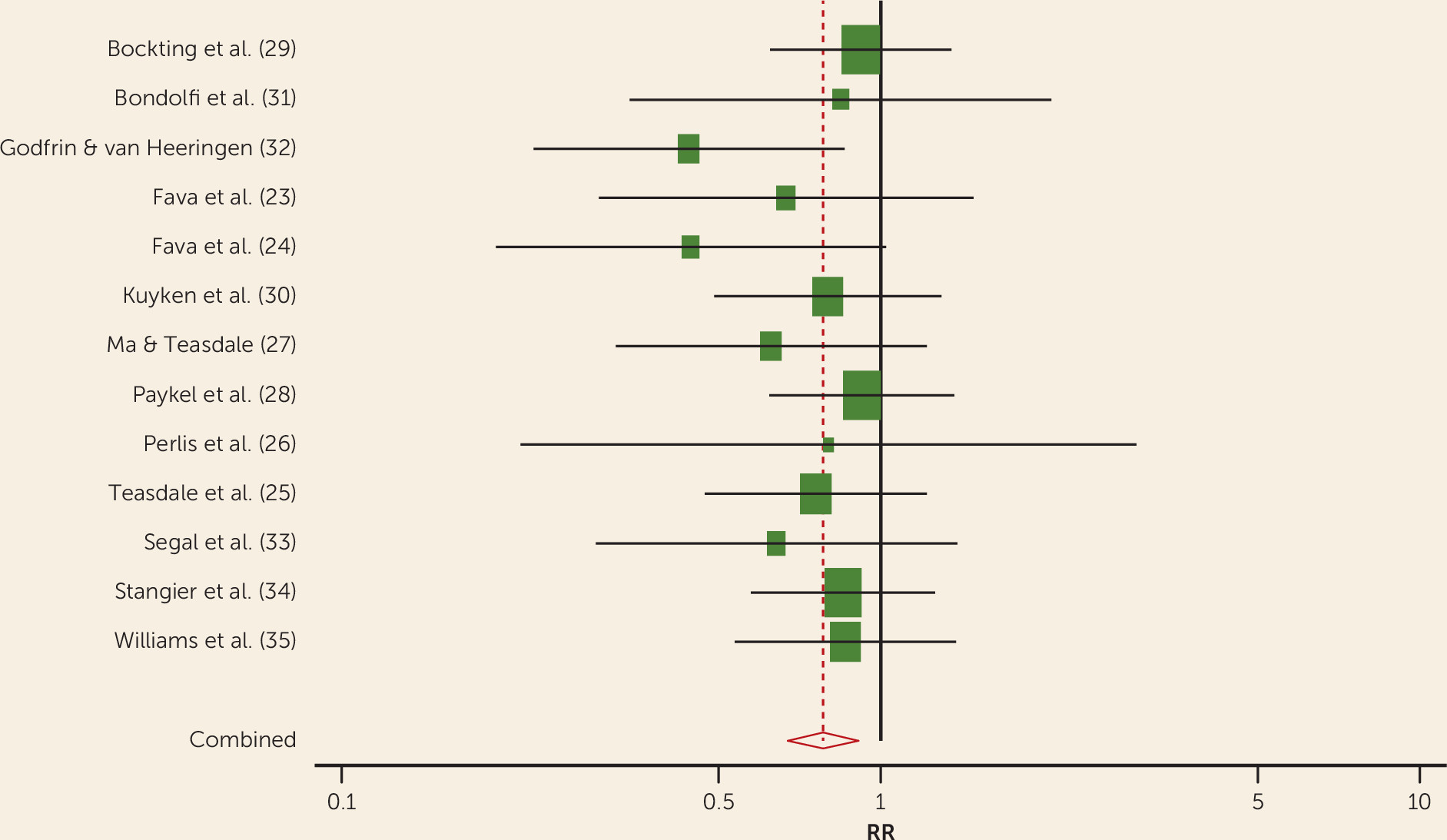

The results of this meta-analysis should be interpreted with caution. First, we found evidence of publication bias that might have led to an overestimation of treatment effects. However, because publication bias is only one of the possible reasons for funnel plot asymmetry, this could reflect the tendency for the smaller studies in the meta-analysis to show larger treatment effects. It is also known that research without statistically significant results could take longer to achieve publication than research with significant results, further biasing evidence over time (time lag bias) (

58). Nonetheless, it seems very unlikely that negative or inconclusive results regarding the efficacy of psychotherapy compared with pharmacotherapy, treatment as usual, or other control conditions in the residual phase of major depressive disorder would remain unpublished. Furthermore, the research designs that have been used may have produced overly optimistic results. Most of the studies compared the sequential approach with treatment as usual, which varied across studies, and differences might have reflected nonspecific effects and expectations (

59). However, highly significant differences were also detected against clinical management that consisted of the same number and duration of sessions as the treatment condition (

23,

24). When active control comparison groups were used, significant differences occurred, even though to a lesser degree compared with other investigations (

28,

30), and the study (

26) that did not report them was characterized by a very short follow-up. Additional limitations are that the sample sizes, the duration of treatments, and the length of follow-up periods varied across the included studies. Nonetheless, meta-regression analyses did not show significant effects on relapse/recurrence rates. No controlled studies, however, have directly compared the use of psychotherapy during antidepressant continuation with tapering and discontinuation. Finally, use of medications in the studies that were included followed a naturalistic pattern, and results might have been different with more aggressive medication dosing aimed to achieving a truly asymptomatic state.

Despite these limitations, our findings lend support to the view that the sequential administration of psychotherapy after response to acute-phase pharmacotherapy, either alone or in combination with antidepressant drugs, may play a role in reducing relapse and recurrence in major depressive disorder.

This can be seen as support for the hypothesis that psychotherapy may generate skills that patients can continue to use after treatment ends to manage their own affective states, reducing internal and external risks for relapse or recurrence. The concept of improvement reflects the distance of the current state of the patient from the pretreatment position (

60). Addition of psychotherapy for a patient who has partially responded to the first line of treatment might result in more favorable ground than in an acute situation, after the first treatment has mobilized the patient’s recovery to its very limit. Comparable learning may not take place with pharmacotherapy alone (

61). Acute depression may impair learning and processing and retrieval of information (

62). Cognitive restructuring and behavioral exposure may thus have more impact when acute depression has abated and may allow detection of under-dosing in drug treatment that the joint use of treatments in the initial phase may mask. In addition, the preventive effects of the sequential strategy appear to be related to abatement of residual symptoms and/or increase in psychological well-being and coping skills (

63–

66). Residual symptoms are among the most powerful predictors of relapse (

65–

67). Anxiety was found to have a prominent role in this symptomatology and in many patients is unlikely to be adequately addressed by one course of treatment, whether pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy (

68). Psychotherapy may thus improve symptoms that the other type of treatment (pharmacotherapy) was unable to affect. This may be particularly important when treatments modulate cortical-limbic pathways in different ways (

69–

72).

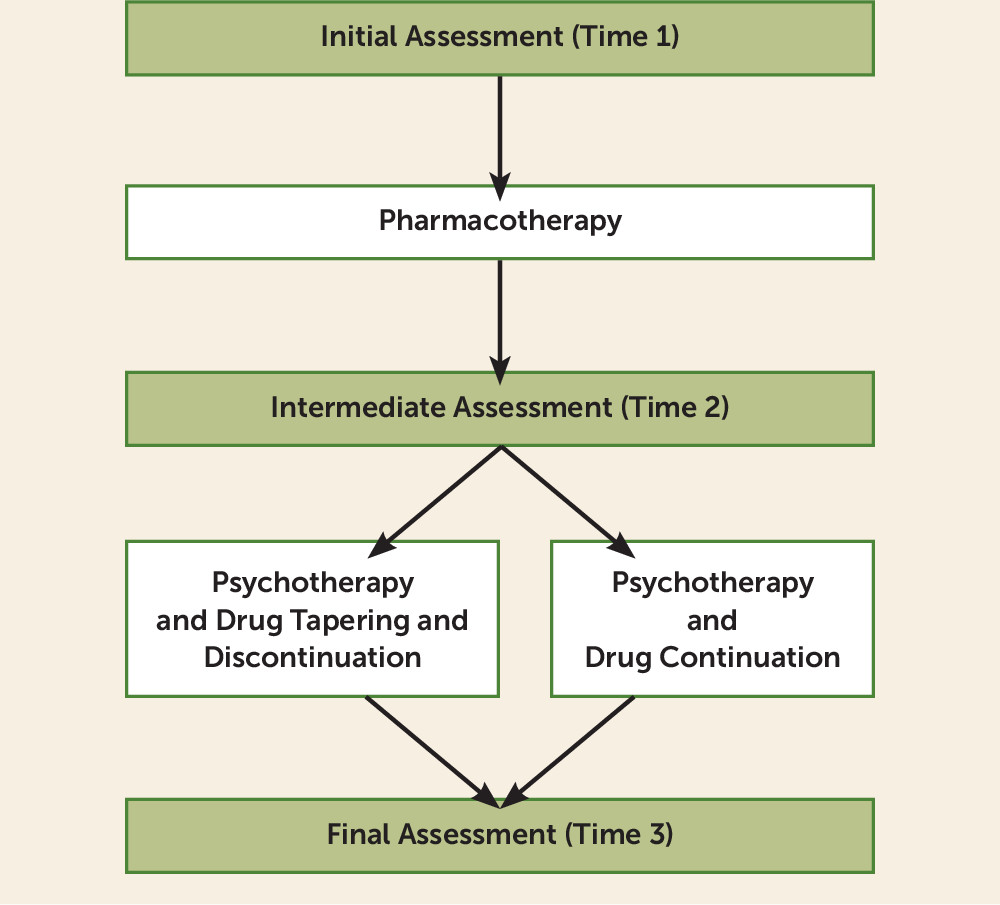

The application of the psychotherapeutic intervention in the sequential model departs from the traditional treatment strategies in depression (

Figure 4). First, it is applied to the residual phase of major depressive disorder according to a longitudinal view of development of disorders that can be subsumed under the staging model (

67). Second, the target of psychotherapeutic work is thus no longer predetermined, but varies according to the nature, characteristics, and intensity of residual symptoms (

7). Third, all the included studies involved cognitive-behavioral treatments, since we could not find any single randomized controlled trial of the sequential use of other well-established psychotherapies (such as interpersonal psychotherapy) after response to pharmacotherapy. However, modifications of cognitive-behavioral techniques, including mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (

73), CBT of residual symptoms (

7), and well-being therapy (

74), were used in most of the studies.

A sequential strategy may include discontinuation of antidepressant drug treatment or its maintenance, thereby offering the advantage of yielding enduring effects while limiting exposure to drug therapy. Performing subgroup analyses, we found a significant effect favoring the combination of psychotherapy and antidepressant medication during the continuation phase compared with treatment as usual or antidepressant medication alone. Furthermore, the sequential use of psychotherapy after discontinuation of antidepressant medication was found to be significantly more effective in reducing relapse/recurrence compared with control conditions (i.e., clinical management or antidepressant drugs). The evidence also suggests that discontinuation of antidepressant drugs is feasible when psychotherapy is provided and may yield enduring results. Indeed, the number needed to treat showed a greater advantage of the sequential option with drug tapering and discontinuation in preventing relapse or recurrence compared with continuation of antidepressants. This is important in view of the fact that a substantial proportion of patients discontinue antidepressant therapy after responding to the initial acute phase treatment, regardless of the physician’s advice (

40).

The sequential model does not appear to be suitable for major depressive disorder of mild severity or minor depression, since the initial treatment with antidepressant drugs may not be warranted. However, when severity is higher, there appear to be several indications. The first indication is provided by recurrent depression. Some individual studies were concerned specifically with recurrent depression (

24,

29–

35), or benefits were more pronounced in case of recurrent depression (

25,

27). There is a tendency to protract drug treatment for long periods of time, with the assumption that it may be protective against relapse. Yet, the evidence becomes questionable in trials of at least 18 months in duration (

42,

75). In a meta-analysis, Kaymaz et al. (

76) found that antidepressants reduce the relapse risk in the maintenance phase. However, patients with multiple depressive episodes experienced significantly less benefit in relapse prevention during the antidepressant maintenance phase compared with those with a single episode. These findings suggest that drug treatment is less helpful in patients who need more protection.

A second indication is provided by the presence of residual symptoms despite response to pharmacotherapy, which appears to be a common finding (

23,

26,

28,

65,

66). Since incomplete recovery from the first lifetime major depressive episode was found to predict a chronic course of illness during a 12-year prospective naturalistic follow-up (

77), this approach appears to be particularly indicated whenever substantial residual symptoms are present.

A third important indication occurs when the physician or the patient or both intend to interrupt drug treatment. The findings of our meta-analysis indicate its feasibility and favorable long-term outcome when this event takes place with the close monitoring of the second phase of the sequential treatment, also in view of discontinuation problems that may arise (

78).

A variation of the sequential model, where the psychotherapeutic approach starts only if and when a loss of clinical efficacy ensues in patients who were fully remitted and in maintenance drug treatment, has been suggested, but its efficacy rests only on two small pilot studies (

79,

80).