Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and pharmacotherapy are, on average, equally and moderately efficacious acute-phase treatments for unipolar depression (

1). For example, 50%−60% of patients receiving CBT or pharmacotherapy for depression respond, compared with 40% receiving pill placebo (

2,

3), and the average CBT or pharmacotherapy patient has posttreatment symptom levels roughly 0.3 SD below those of patients receiving pill placebo (

4,

5). However, these favorable averages may obscure some patients’ negative outcomes (

6). Moreover, beyond conventionally defined response (≥50% symptom reduction) and remission (posttreatment scores ≤7 on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale [HAM-D] [

7]), only patients with unusually positive outcomes have no residual symptoms with attendant dysfunction (

8).

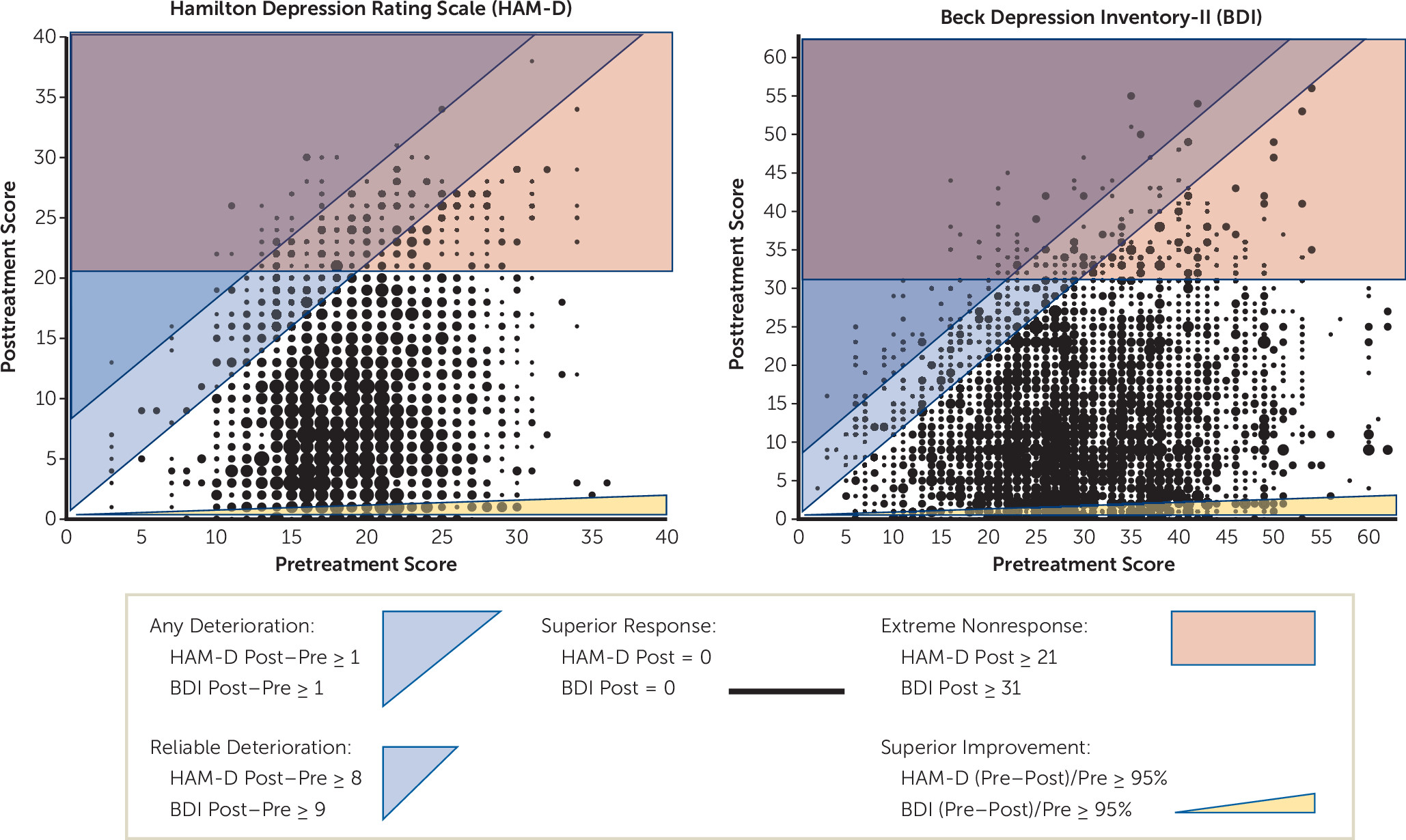

In this study we focused on patient-level treatment outcomes diverging from the average. We analyzed two specific negative outcomes: deterioration (symptom severity increases from pre- to posttreatment) (

9) and extreme nonresponse (severe depressive symptoms posttreatment) (

10), although many others are possible (

11). Complementarily, we defined two unusually positive outcomes: superior improvement (≥95% symptom reduction from pre- to posttreatment) and superior response (no depressive symptoms posttreatment). We estimated the frequency of these outcomes and tested antecedents in a large patient-level database (N=1,700) pooled from 16 randomized clinical trials comparing CBT to pharmacotherapy. Such analyses may clarify which patients are more likely to have negative or unusually positive outcomes, help match treatments to patients, and through such matching increase treatments’ overall benefits (

12).

The frequency and causes of deterioration, extreme nonresponse, superior improvement, and superior response in CBT and pharmacotherapy for depression are unclear. Perhaps 5%−10% of psychotherapy patients show reliable deterioration (increases exceeding the symptom measure’s reliable change threshold), with evidence of higher risk among children than adults, in routine practice compared with randomized clinical trials, and in psychotherapy considered more broadly than CBT specifically (

9,

13). Reliable deterioration may occur with similar frequency in pharmacotherapy for depression (

14). The concept of extreme nonresponse was introduced in CBT research (

10), but observed rates have varied widely in CBT patients, 6% (

15) in one sample and 22% in another (

10). Finally, based on distributions of symptom scores, superior response and superior improvement possibly occur in <10% of treated depressed patients (

8,

16). The current large-sample analyses were designed to clarify these outcome frequencies in pharmacotherapy versus CBT for depression.

Patient characteristics may predict negative and unusually positive outcomes in CBT or pharmacotherapy for depression. Pretreatment markers of greater pathology (e.g., comorbidity, suicidality, unemployment, prior hospitalizations) have predicted less improvement in CBT (

17,

18) and pharmacotherapy (

19,

20). In addition, higher pretreatment levels of depressive symptoms, plus poorer pretreatment functioning and therapeutic alliance, have predicted extreme nonresponse in CBT (

10,

15). Broadly, pretreatment symptom levels may relate directly to posttreatment symptom levels but inversely to the direction of symptom change (

21). Thus, greater pretreatment severity may predict higher probabilities of extreme nonresponse and superior improvement but lower probabilities of superior response and deterioration. In contrast, demographic variables have been inconsistent predictors of CBT or pharmacotherapy outcomes (

18,

22), perhaps because detecting modest effects without large individual-patient samples is difficult.

Whether treatments or illness trajectories cause particular outcomes is difficult to determine (

6). Unipolar depression is often episodic, and mood reactivity within episodes is common (

23). Thus, deterioration and extreme nonresponse could be adverse effects of treatment, unrelated to treatment, or even benefits of treatment (i.e., some patients would have been worse off untreated). Similarly, superior improvement and superior response may sometimes reflect “spontaneous” improvements due to biochemical, learning, or life events unrelated to treatment.

The goals of this study were to 1) estimate the proportions of patients with negative outcomes (deterioration, extreme nonresponse) and unusually positive outcomes (superior improvement, superior response) in CBT or pharmacotherapy for depression; 2) test predictors of these outcomes, including the type of treatment (CBT versus pharmacotherapy) and patient demographic and clinical characteristics; 3) test whether patient characteristics moderate the effects of treatment (CBT versus pharmacotherapy) on these outcomes; and 4) contrast pretreatment characteristics of patients with opposing outcomes (deterioration versus superior improvement; extreme nonresponse versus superior response).

Discussion

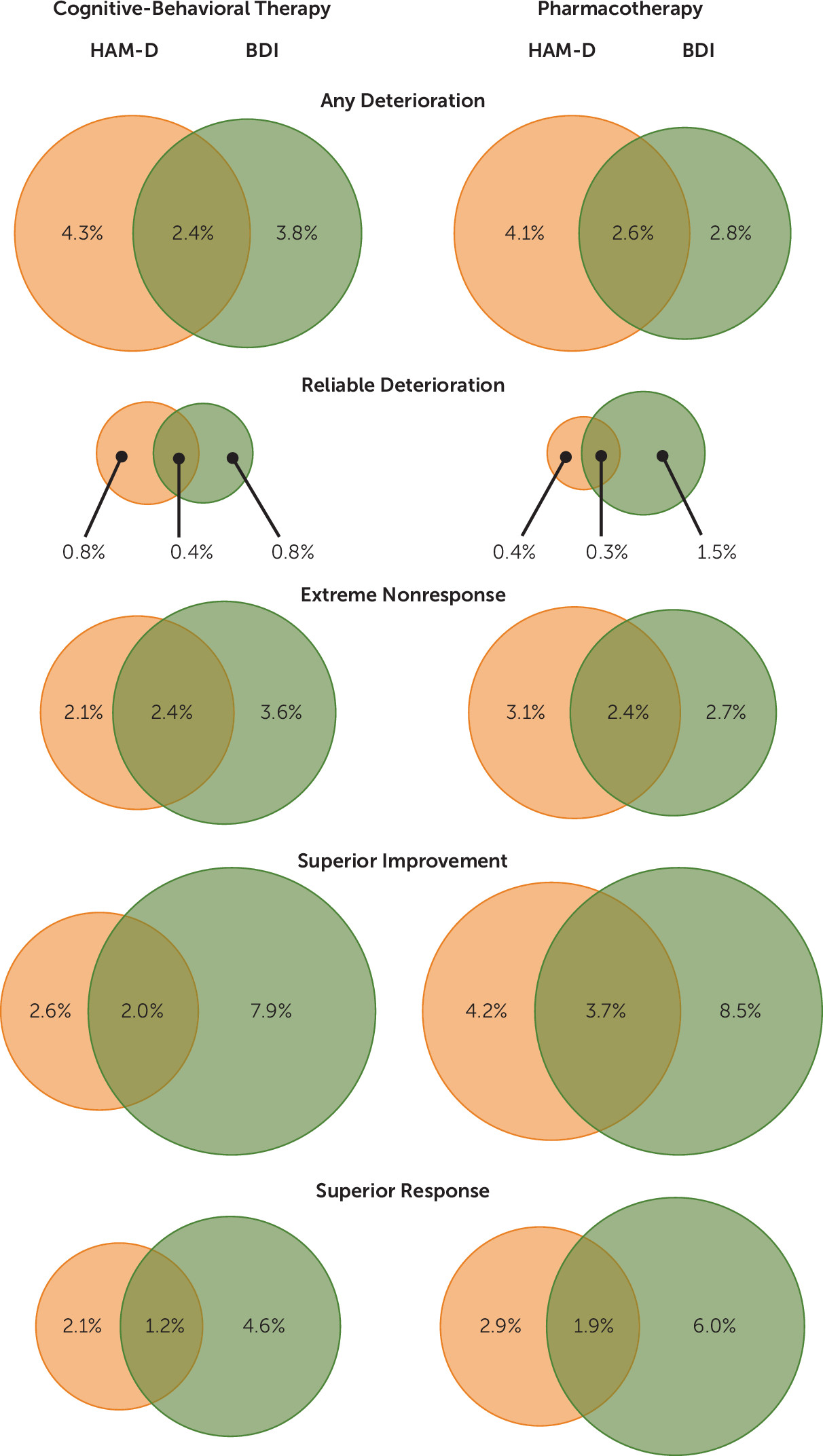

Among 1,700 depressed patients from 16 randomized clinical trials comparing CBT to pharmacotherapy, we found that 13% experienced negative and 15% experienced unusually positive symptomatic outcomes. The analyzed negative outcomes were any deterioration (5%−7% had increases of ≥1 HAM-D or BDI points), reliable deterioration (1% had increases ≥8 HAM-D or ≥9 BDI points), and extreme nonresponse (4%−5% had posttreatment HAM-D scores of ≥21 or BDI scores of ≥31). Negative outcomes may be more common in practice settings outside of research (

12,

14) because frequent assessment of patients, feedback to clinicians about patients’ progress, and monitoring of treatment fidelity (e.g., clinicians’ competence and protocol adherence) in many randomized clinical trials parallel interventions shown to reduce deterioration (

13). Patients’ unusually positive outcomes included superior improvement (6%−10% had HAM-D or BDI score decreases ≥95%) and superior response (4%−5% had posttreatment HAM-D or BDI scores of 0). Because few patients receiving CBT or pharmacotherapy reached absent (superior response) or minimal (superior improvement) residual depressive symptoms, our results highlight the potential value of continuing, sequencing, or augmenting treatments (

19,

33).

Treatment with pharmacotherapy versus CBT increased patients’ odds of superior improvement from the clinician’s perspective (HAM-D: 7.7% versus 4.8%) but not from the patient’s (BDI). Pharmacotherapy also predicted greater attrition relative to CBT (18.5% versus 12.0%), and among the subset of studies with placebo arms, fewer negative outcomes overall relative to pill placebo (16.2% versus 24.8%). If replicated, more frequent superior improvement during pharmacotherapy than in CBT may signal operation of an unknown moderator (e.g., to be revealed by genotyping) among patients who tolerate treatment (e.g., do not drop out). In addition, younger age (among adults) predicted superior improvement on the HAM-D, whereas employment predicted superior response on the BDI. These latter findings fit broader patterns of better outcomes for patients with less (versus more) severe pathology (

17–

20). Treatment modality did not change patients’ odds of deterioration, extreme nonresponse, or superior response on the HAM-D or BDI.

Pretreatment symptom levels predicted outcomes and varied significantly between patients with negative versus unusually positive outcomes. In general, pretreatment symptom levels related directly to posttreatment symptom levels and inversely to the direction of symptom change. More specifically, lower pretreatment symptom severity increased risk for deterioration, and patients who deteriorated had lower pretreatment symptom levels than did patients with superior improvement, within measures (HAM-D or BDI). In addition, higher pretreatment symptom levels increased the odds of superior improvement within the HAM-D only. Specific depressive symptoms (HAM-D items) most relevant to these predictions included less depressed mood, less guilt, and fewer general somatic symptoms (deterioration) and more gastrosomatic symptoms (superior improvement).

Psychotherapy may produce negative outcomes, or fail to evoke unusually positive outcomes, when psychotherapists are confrontational and over-interpret common experiences and patient characteristics as pathological (

34). However, lack of generalization across measures in our analyses of deterioration and superior improvement also suggests methodological artifacts, such as regression to the mean within measures. The patient (BDI) and clinician (HAM-D) measures may also capture somewhat different information (

35) and have finite reliability and validity (

36), as do all measures. Finally, patients with lower pretreatment symptom scores may be entering treatment as a depressive episode is waxing, and their deterioration and lack of superior improvement during treatment might reflect the natural course of illness.

Higher pretreatment depressive symptom levels also predicted extreme nonresponse, and patients with extreme nonresponse had higher pretreatment symptom levels than did patients with superior response, both within and between the HAM-D and BDI. In addition, lower pretreatment symptom levels increased patients’ odds of superior response on the BDI. Specific depressive symptoms (HAM-D items) that predicted extreme nonresponse on the HAM-D included initial insomnia, middle insomnia, and weight loss. Although CBT and pharmacotherapy benefit many severely depressed patients (

37), our analyses suggest that severe depression at the beginning of treatment adds risk for severe depression and reduces the likelihood of being symptom-free at the end of pharmacotherapy or CBT.

The pretreatment symptom levels and patient characteristics analyzed here (age, gender, education, ethnicity, pretreatment symptom severity, double depression, comorbidity) did not moderate treatment effects on deterioration, extreme nonresponse, superior improvement, or superior response. Consequently, the current results do not support differential treatment selection (CBT versus pharmacotherapy) from symptom levels and patient characteristics to prevent negative or potentiate unusually positive outcomes. Other patient characteristics or events outside of treatment may account for these outcomes and are potential targets for future research. Even so, empirical guidance for selecting CBT or pharmacotherapy for a given patient based on average posttreatment symptom scores is available (

16,

38).

On the basis of the current findings, we recommend assessing symptom levels frequently and longitudinally (especially among patients with high pretreatment severity) and pursuing rapid corrective action (e.g., increased session frequency, switching or augmenting treatment) if patients do not progress adequately (

12). However, other negative outcomes and adverse events, including discrete behaviors (e.g., suicide), psychosocial outcomes (e.g., divorce; domestic violence), dropping out of treatment, and medication side effects (e.g., sexual dysfunction) arguably are distinct from depressive symptom levels (

11) and may require different preventive efforts. Similarly, positive outcomes distinct from depressive symptoms are also important therapeutic targets (e.g., social-interpersonal functioning) (

39).

The current study has additional limitations that temper our conclusions. For example, although the sample was large, low base rates of divergent outcomes and attrition may have limited detection of predictors and moderators. In addition, many important patient characteristics (e.g., personality profiles, depressive cognitive content, therapeutic alliance, social support) were not analyzed and could be targets for future research on predictors and moderators of divergent outcomes (

10,

40). Moreover, our results from randomized clinical trials may not generalize fully to routine clinical practice (

12,

14). Similarly, generalization of our findings to other negative outcomes (e.g., adverse events, side effects) or positive outcomes (e.g., improvement in work or social functioning) not studied here is unknown. Finally, our analyses focused on trials of CBT versus pharmacotherapy and do not address combinations, sequences, dissemination, or the quality of implementation of treatments.

Preventing negative and potentiating unusually positive outcomes may improve the overall efficacy of CBT and pharmacotherapy for depression. In this effort, future research might profitably test replication and mechanisms of the current findings. For example, greater odds of clinician-rated superior improvement among younger (versus older) adults and those treated with pharmacotherapy (versus CBT) and greater odds of patient-rated superior response for patients with full-time (versus less) employment possibly reflect measurable intrapatient, environmental, or interacting mechanisms. Similarly, specific depressive symptoms linked with clinician-rated extreme nonresponse (insomnia, weight loss), deterioration (less depressed mood, less guilt, fewer general somatic symptoms), and superior improvement (gastrosomatic symptoms) may reflect sampling or measurement error but may also reveal patient subpopulations with different treatment-response trajectories.

The current results clarify expectations for outcomes in acute-phase CBT or pharmacotherapy for adult depression. First, whereas the majority of patients responded by conventional standards (

32), we found that a few patients (13%) had negative outcomes and some (15%) had very positive outcomes. Second, pretreatment symptom levels help forecast negative and unusually positive outcomes: Patients with severe pretreatment symptoms are more likely to have large drops in symptoms (superior improvement) and unlikely to get worse (deteriorate), but they are also more likely to end treatment with severe symptoms (extreme nonresponse) and are unlikely to end treatment symptom-free (superior response). Conversely, patients with milder pretreatment symptoms are more likely to end treatment symptom-free (superior response) and unlikely to end treatment with severe symptoms (extreme nonresponse), but they are also more likely to get worse (deteriorate) and less likely to have large drops in symptoms (superior improvement). Finally, choosing pharmacotherapy versus CBT may increase patients’ odds of both discontinuing treatment and clinician-rated superior response.