The high prevalence of chronic pain and increases in the prevalence and adverse events associated with opioid prescriptions have brought to the fore the need to examine the relationship between chronic pain and prescription opioid use disorders (

1,

2). Pain is a prevalent condition, with recent estimates suggesting that chronic pain affects approximately one-third of the U.S. population and constitutes one of the most common symptoms for which patients seek medical attention (

3). It is associated with intense personal suffering, high rates of disability, and an annual economic burden surpassing half a trillion dollars due to costs of medical treatment and productivity losses (

4).

Concerns about undertreatment of pain have led to growth in opioid prescriptions and an increase in the prevalence of prescription opioid use disorders, which themselves pose risks of premature mortality (

5,

6). Despite the clinical, public health, and policy relevance of prescription opioid use disorder, little is known about its relationship to pain. Information about these relationships bears directly on the development of guidelines and legislation to ensure the safe treatment of pain and minimize the risk of addiction to prescription opioids (

7,

8). Several cross-sectional studies have indicated that pain is associated with an increased risk of prescription opioid use disorders (

9,

10), and concerns have been raised that individuals with opioid use disorders may develop abnormal pain sensitivity or hyperalgesia (

11). Surprisingly, however, no study has examined prospectively the relationship between pain and prescription opioid use disorders in a nationally representative sample.

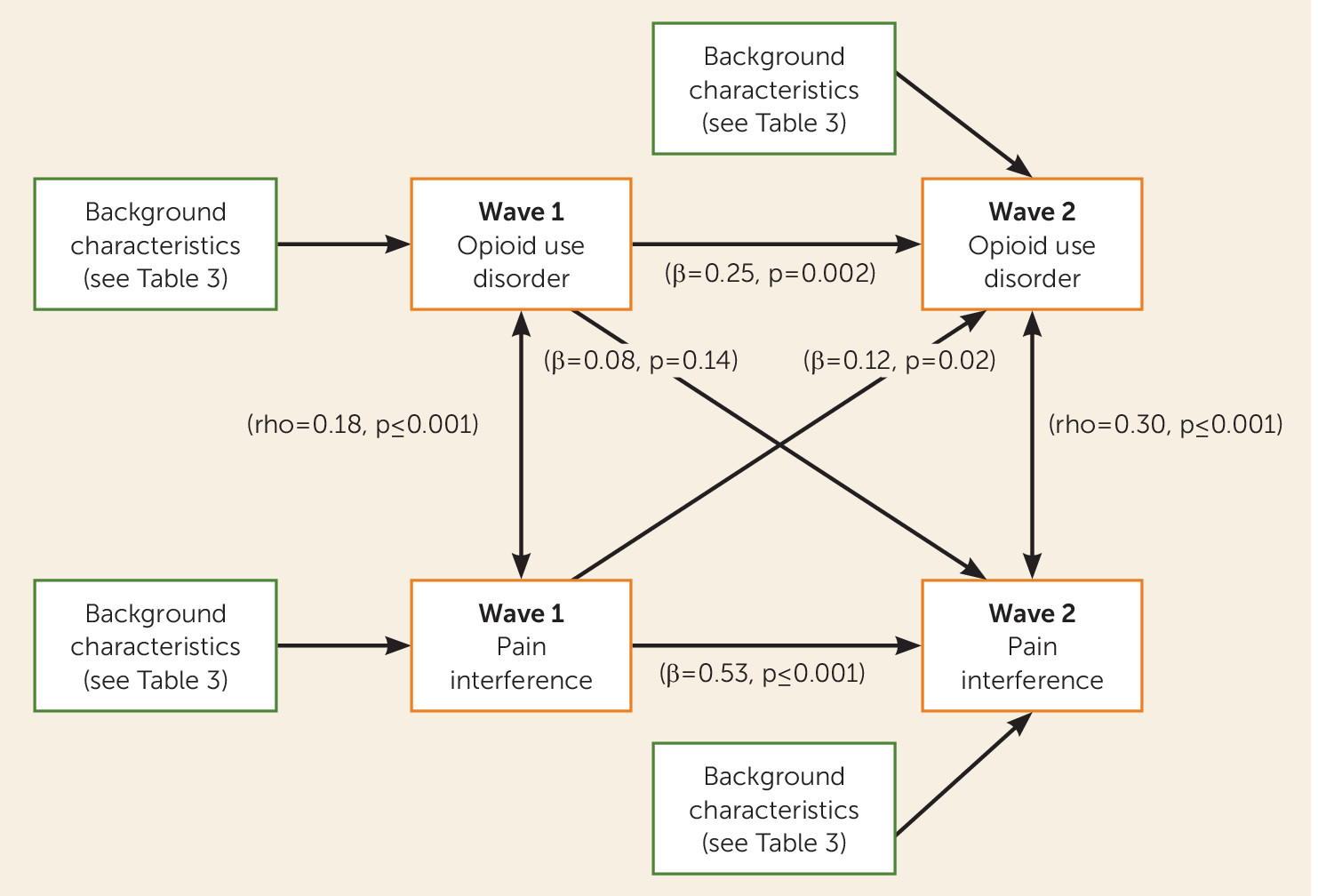

We sought to address this gap in knowledge with prospective data from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), a large, nationally representative sample. We examined whether the presence of pain increased the risk of developing a prescription opioid use disorder 3 years later and, conversely, whether prescription drug use disorders increased the subsequent risk of developing pain, after adjusting for several relevant demographic and clinical covariates.

Discussion

In a nationally representative sample assessed twice 3 years apart, pain and prescription opioid use disorders were associated with one another at both time points. However, whereas pain at baseline was associated with prescription opioid use disorder at follow-up, prescription opioid use disorder at baseline was not associated with pain at follow-up. The results were consistent across different modeling strategies, indicating the robustness of the findings. Several demographic and clinical correlates were also directly associated with both pain and prescription opioid use disorders. Furthermore, older age decreased the risk of prescription opioid use disorder but increased the risk of pain, whereas male as compared with female sex increased the risk of prescription opioid use disorder but decreased the risk of pain.

Our first major finding was an association between pain at baseline and disorder-level prescription opioid use at follow-up that was independent of the demographic and clinical factors. The path for pain interference was associated with a 41% relative increase in the risk of developing a prescription opioid use disorder. This prospective association extends results from cross-sectional studies that have documented a link between pain and prescription opioid use disorders (

10). Persistent pain may lead some individuals to use prescription opioids in patterns different from what their prescribing physician intended, leading to tolerance and withdrawal symptoms and eventually to opioid abuse or dependence. Pain, an extremely powerful motivator, may also lead individuals to discount the long-term risks of their actions in an urgent effort to suppress pain. Because both pain and opioids can activate dopamine release in their acute phase, they may share some neurobiological mechanisms in the brain reward and motivational systems (

30). Complex biological interactions related to pain or inflammation, which often accompanies pain, may also alter opioid receptors and increase the risk of addiction (

31).

In order to reduce the long-term risk of prescription opioid use dependence in individuals with chronic pain, ongoing assessment of pain, consideration of alternative treatments, and treatment of comorbid medical or psychiatric conditions may be useful (

32). Use of tamper-resistant medications or partial opioid agonists such as buprenorphine may also help provide adequate treatment while minimizing the abuse potential (

33). Outside of supervised settings, reducing opioid use in patients with chronic pain is often clinically challenging and quite difficult to achieve and maintain (

34). Our findings highlight the need to provide evidence-based treatment for individuals in pain and to develop more effective nonopioid alternative treatments for those who do not respond to existing options.

Our second major finding was that prescription opioid use disorder was not significantly associated with pain at 3-year follow-up after accounting for potential confounding covariates. This contrasts with findings from cross-sectional studies of clinical samples of individuals in methadone programs (

35) and in some (

36), although not all (

37), studies of patients with acute perioperative exposure to opioids. However, our prospective results are consistent with findings from patients with chronic pain (

11,

38) and with the results of the only randomized trial prospectively examining opioid-induced hyperalgesia. In that trial, patients with chronic back pain treated with oral morphine were no more likely than those assigned to placebo to develop hyperalgesia (

39).

Consistent with previous studies, several demographic and clinical factors were associated with prescription opioid use disorders and pain (

10,

40,

41). These findings converge to highlight the complexity of factors that influence the development and maintenance of pain and prescription opioid use disorders and the challenge of studying these phenomena. From the clinical and preventive perspective, these clinical and demographic characteristics identify subgroups at increased risk who should be screened for pain and prescription opioid abuse. They may also reflect overlaps in the etiology of pain, prescription opioid use disorders, and other psychiatric disorders (

42), and they support recent interest in developing transdiagnostic approaches to psychiatric disorders and symptoms (

43,

44).

This study has several limitations. First, the NESARC sampled individuals age 18 and older, and the relationship between pain and prescription opioid use disorders may differ in younger individuals. Second, pain was assessed only at two time points 3 years apart, precluding the assessment of the relationship between pain and prescription opioid use disorder using other time frames (e.g., lifetime) or over longer periods. Furthermore, the data were collected a decade ago. Nevertheless, the NESARC remains the most recent nationally representative cohort of U.S. adults. Third, the NESARC did not assess inmate populations, which may have a higher prevalence of substance use disorders (

45). Fourth, the assessment of nonmedical use of prescription opioids, although extensive, was not exhaustive. In addition, it included two nonopioid medications (celecoxib and rofecoxib). However, because these medications do not have addictive potential, they are unlikely to have led to prescription drug use disorders and thus to have biased the estimates of the study. Fifth, the NESARC did not ask how individuals obtained their medications. Sixth, as in any complex model, the estimates of the associations should be interpreted with caution and taking into account that they are not independent associations, but rather adjusted for the other covariates in the model. Finally, the NESARC assessed pain with a single item and did not query about the location or duration of the pain.

In a large nationally representative sample, pain predicted opioid use disorder. We hope that this finding helps to focus research and practice on development and use of nonopioid strategies for pain management.