The aim of depression treatment is sustained symptom remission and functional recovery (

1–

4). Full remission of all symptoms of a major depressive episode (as opposed to symptom improvement to a subsyndromal status) is far more likely to lead to a stable well period with good everyday functioning (

5,

6) and a lower risk of depressive episode relapse (

4–

6). We previously reported (

6) that among 197 patients in the National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Depression Study who achieved full remission from a major depressive episode, the rate of relapse was 16% over the next 6 months and 26% over 1 year. Others have also noted a modest but meaningful rate of relapse among depressed patients who have achieved complete remission (

7,

8).

We currently have no patient-level indicators with which to plan care for individual depressed patients who have reached remission. Current guidance recommends visits every 1 to 6 months based on clinical judgment. However, if we could develop a clinical tool for estimating the likelihood of relapse for a given patient after complete remission, we would be able to tailor the follow-up visit schedule individually. Patients more likely to relapse could be followed up more often, in person or by telephone, whereas those at lower risk of relapse could be seen less frequently. Care would be more efficient, and, if needed, interventions could be delivered in a more timely fashion to patients with impending or actual relapses.

Method

Subjects were drawn from the National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Depression Study of 955 patients seeking treatment for a major affective episode at five U.S. academic centers between 1978 and 1981 (

10,

11). Intake diagnoses were made by Research Diagnostic Criteria (

12) based on Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia interviews (

13). The study was a naturalistic, prospective, longitudinal study of illness course, in which patients were periodically and systematically followed for up to 31 years. Treatment was recorded, not controlled. Patients had to be white (to test genetic hypotheses), speak English, have an IQ ≥70, and have no organic brain syndrome or terminal medical illness. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient.

The resulting database includes detailed information on psychiatric history, index episode characteristics, and follow-up data on weekly clinical status, somatic treatment, and psychosocial functioning gathered from self-reports, family informants, medical and research records, and ratings by trained clinical interviewers.

The sample for the present study was drawn from 487 patients with no lifetime bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, or schizophrenia who entered the Collaborative Depression Study in an active major depressive episode, defined by Research Diagnostic Criteria as ≥2 consecutive weeks with at least five depressive symptoms, including intense sadness or dysphoria.

Follow-Up

Trained professional raters completed the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation (

14) every 6 months for the first 5 years and yearly thereafter, using semistructured interviews. The interviewers used chronological memory prompts (e.g., birthdays and holidays), supplemented by available medical and research records, to establish changes in weekly symptom severity for all disorders defined by the Research Diagnostic Criteria. Raters were rigorously trained, resulting in intraclass correlation coefficients of 0.92 for reliability of psychiatric symptom change points, 0.95 for recovery from affective episodes, and 0.88 for subsequent appearance of affective symptoms (

14). Results were recorded on Longitudinal Follow-Up Evaluation interviews as weekly psychiatric status ratings, with scale values anchored to diagnostic thresholds defined by the Research Diagnostic Criteria (

12).

Severity ratings for depressive conditions were combined for each week during follow-up and classified into one of four mutually exclusive categories: met diagnostic threshold for a major depressive episode, met diagnostic threshold for a minor depressive episode, had subsyndromal depressive symptoms below either diagnostic threshold, and asymptomatic status (no symptoms of the episode, return to usual self).

Periodic Symptom Self-Report

Subjects completed the SCL-90 self-report at intake and at either 6-month or yearly intervals thereafter for 5 years, during the same visit when Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation interviews were conducted. On the SCL-90, respondents indicate the degree to which they have been “bothered or distressed” by each of 90 symptoms “during the past week or so” on a 5-point scale ranging from “not at all” to “extremely.” The SCL-90 is typically scored for nine symptom domains: somatization, obsession/compulsion, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, anger-hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism. Domain scores have been developed and validated for various clinical and nonclinical populations (

15,

16).

Selection of SCL-90 Records During Full Remission From Depressive Episodes

For this study, we analyzed the SCL-90 records obtained when those patients with major depressive disorder were in remission—defined as having a psychiatric status rating of 1 (asymptomatic, returned to usual self with no symptoms of the episode)—from major depression, minor depression, dysthymia, intermittent depression, atypical depression (DSM-III code 296.82), or adjustment disorder with depressed mood (DSM-III code 309.00) during the SCL-90 week and the previous 8 weeks. Mean time asymptomatic was 86.2 weeks (SD=64.4, range=9–262). Because we sought to identify predictors of relapse that occurred within the next 6 months, we selected only those SCL-90 records that were followed by uninterrupted weekly psychiatric status rating data for at least 26 weeks. Depressive relapse was defined as 2 consecutive weeks of psychiatric status ratings at the threshold for defining an episode of major or minor/dysthymic depression.

Statistical Analysis

For analysis, we converted each SCL-90 symptom item response into a binary response. We defined clinically meaningful symptom levels a priori as those rated 2 (bothered moderately), 3 (quite a bit), or 4 (extremely). Items rated as 0 (not bothered at all) or 1 (only a little bit) were considered not clinically meaningful.

We first examined the overall rate of all clinically meaningful SCL-90 symptoms during full remission. We then compared these symptom ratings by whether or not relapse occurred within the subsequent 6 months, based on mixed-model logistic regression, taking into account within-subject correlations for those subjects with repeated assessments.

Seventeen SCL-90 items significantly distinguished relapse from nonrelapse. Forward and backward stepwise mixed-model logistic regression was performed to identify 12 of these 17 symptoms that, together, were maximally predictive of short-term depressive relapse. Reduction in the −2 log likelihood ratio test was used to determine improvement in prediction with inclusion or exclusion of each variable, since it is a fit statistic that does not include a penalty for the number of predictors in the model. A complete set of predictive statistics (sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, positive likelihood ratio, and negative likelihood ratio) was computed for each number of symptoms in the final set of 12 predictors.

Data analysis was performed using SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.) and the SuperMix mixed-effects regression models program package (Scientific Software International, Skokie, Ill.), which combines the functionality of MIXOR and other mixed-effects programs developed by Hedeker and Gibbons (

17).

Results

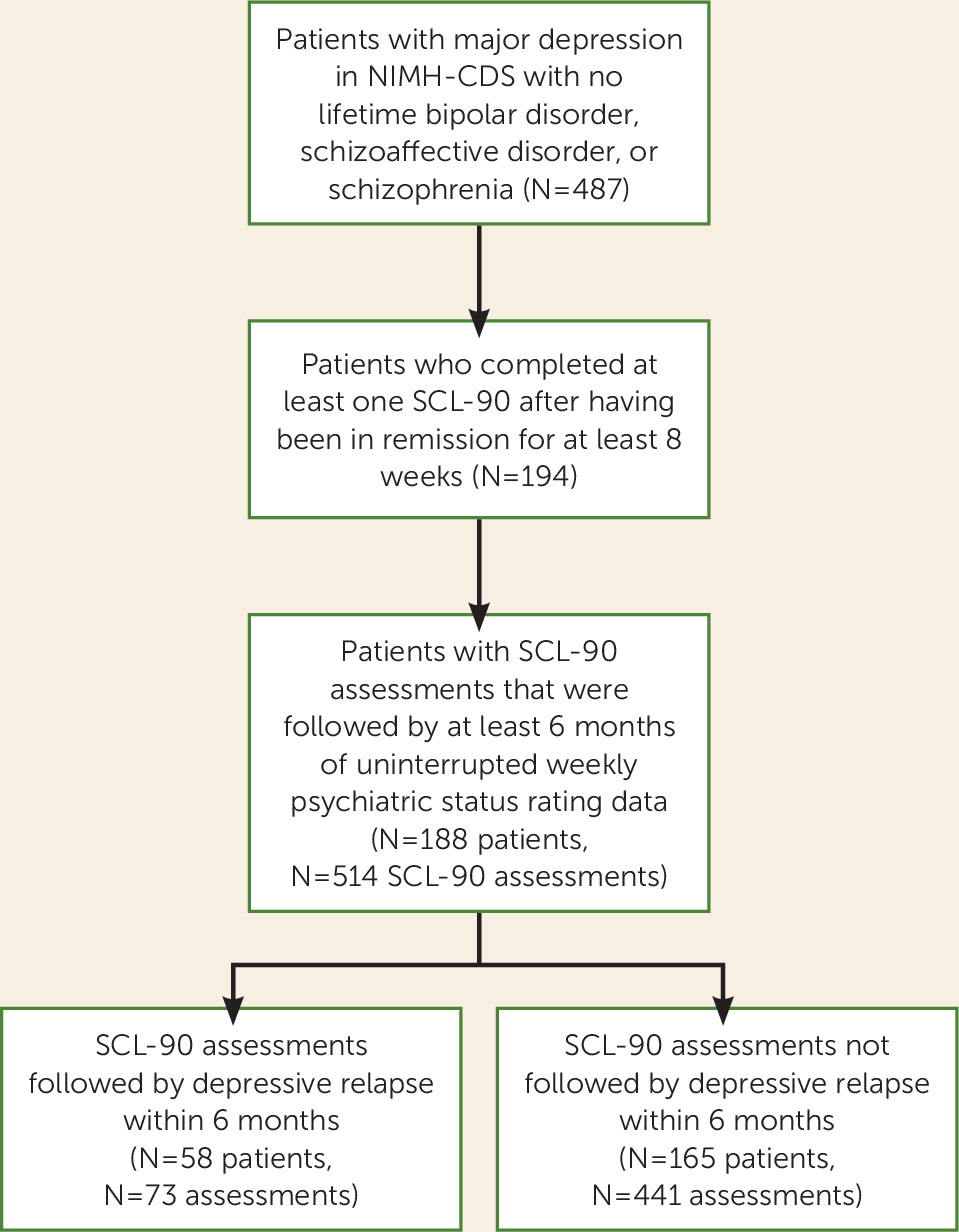

Figure 1 illustrates the formation of the analytic sample, which consisted of 188 patients who provided 514 SCL-90s. Majorities of the sample were female (58.5%), had at least some college education (56.4%), and were married or living with a partner (56.4%); 15.0% were separated, divorced, or widowed, and 28.5% had never been married. The mean age was 37.8 years (SD=14.4, range=18–74). About one-third (34.0%) were in their first depressive episode at study intake, 43.6% had experienced one or two previous episodes, and the remaining 22.3% had three or more previous episodes. Most subjects (71.8%) were inpatients at intake. The mean Global Assessment Scale (

18) score for the worst period in the intake episode prior to intake (on a scale of 1–100, with higher numbers indicating better function) was 39.4 (SD=10.0, range=5–65), reflecting major impairment in several areas of functioning, or some impairment in reality testing or communication, or one or more suicide attempts.

The analytic sample consisted of 514 SCL-90 records following fully remitted periods, including 73 records (14.2%) (in 58 subjects) that were followed by a depressive episode relapse within the next 6 months and 441 records (85.8%) (in 165 subjects) that were free of relapse for 6 months or longer (

Figure 1). The number of SCL-90 records per subject varied; 62 subjects contributed one SCL-90 record to the analysis, and the remainder had from two to 10 assessments. Among the 188 subjects, 130 (69.2%) had SCL-90 assessments followed only by nonrelapse status, 23 (12.2%) only by relapse status, and 35 (18.6%) by a mixture of nonrelapse and relapse.

Depressive relapse within 6 months could not be ascribed to receiving less intensive antidepressant treatment. The level of composite antidepressant treatment (on a 0–4 scale based on imipramine equivalents) was significantly higher for SCL-90 assessments that were followed by relapse than for assessments that were not (mean=1.11 [SD=1.37] compared with mean=0.69 [SD=1.25]; p=0.01). More assessments followed by relapses were associated with receiving any antidepressant than those not followed by relapse (N=34 [46.6%] compared with N=120 [27.2%]; p<0.001).

To assess the clinical impact of these relapses, we looked at the 5-year course of illness after the SCL-90 assessments. The SCL-90s that were followed by relapses were associated with a worse course of illness over the next 5 years, as indicated by a significantly greater percentage of time spent at each level of severity of depressive symptoms and proportionately fewer asymptomatic weeks (

Table 1).

Table 2 lists the rates of 19 SCL-90 symptoms that occurred at a clinically meaningful level in at least 15% of the SCL-90s during this period of remission. We have grouped symptoms into clinically related categories, independently of the standard SCL-90 scoring key. The most common symptoms were features of anxiety, depression, and anger-irritability. Sleep disturbance and somatic complaints also occurred in 15% or more of the SCL-90s.

The first step in developing a clinical scale to distinguish risk of relapse compared with nonrelapse in the next 6 months was to identify SCL-90 symptoms that, when rated as at least moderately severe during the past week, significantly differentiated relapse from nonrelapse. After a Bonferroni correction (

19) based on seven of the nine SCL-90 subscales that were relatively independent, 17 SCL-90 items that differentiated relapse from nonrelapse at p<0.0071 were considered statistically significant. Beginning with these 17 symptoms, the 12 symptoms in boldface in

Table 3 contributed to prediction of relapse within 6 months based on forward- and backward-stepping mixed-model logistic regression.

We found that experiencing any one or more of the 12 symptoms most predictive of relapse at a moderate or worse level of severity in the past week resulted in a sensitivity of 80.8% for identifying relapse occurrences within the next 6 months and a specificity of 51.2% for identifying true nonrelapses (

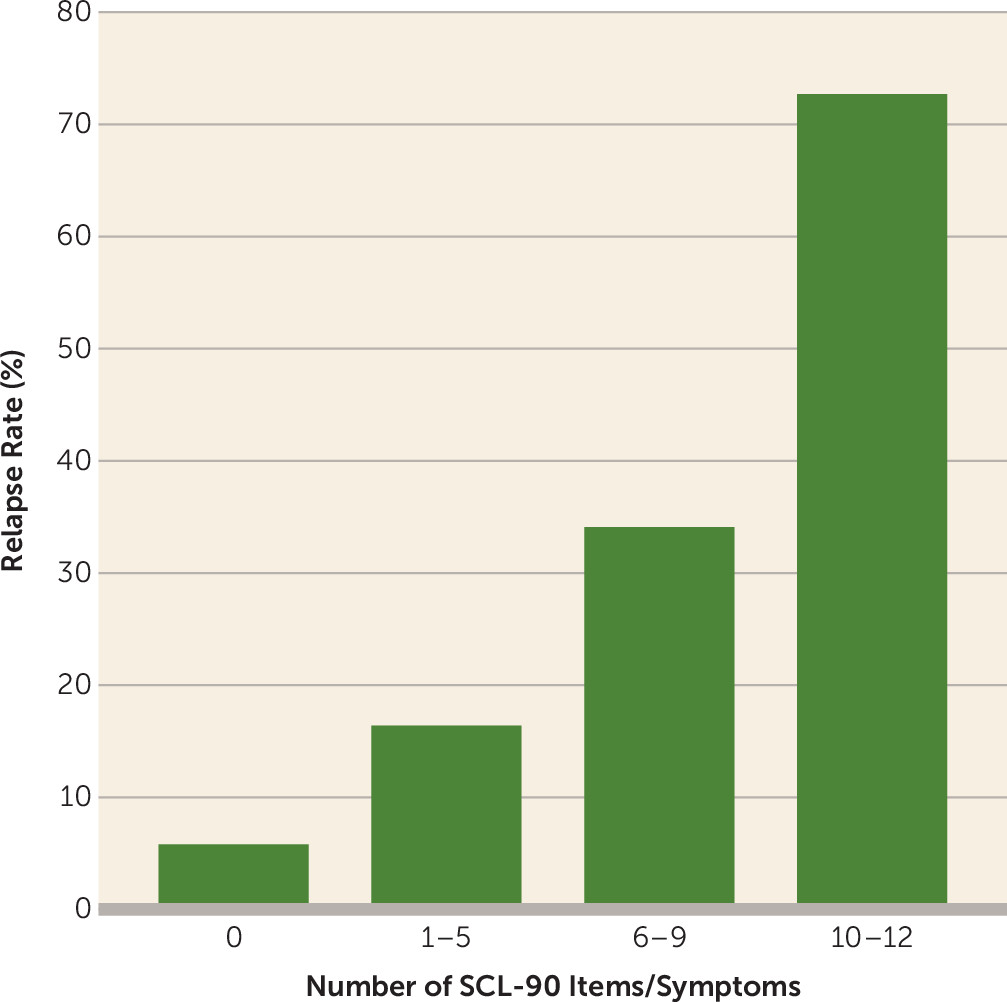

Table 4). The generally accepted level of 80.0% specificity in identifying true nonrelapse occurrences was met when four or more of the 12 symptoms were present. After at least 8 weeks of full remission, if one or more of the 12 SCL-90 symptoms was experienced at a moderate or worse level, most (80.8% sensitivity) of the actual relapses were detected, but only 21.5% of such assessments were actually followed by a relapse (positive predictive value). On the other hand, if none of the 12 symptoms were endorsed, about half of the actual nonrelapses were identified (51.2% specificity), but with a very high certainty of actually not having a depressive relapse (negative predictive value of 94.2%). Having none of the 12 symptoms was associated with a 5.8% rate of relapse within the next 6 months; the rate increased to 16.4% for one to five symptoms, 34.1% for six to nine symptoms, and 72.7% for 10–12 symptoms (

Figure 2). Detailed counts for these ranges are provided in Table S1 in the

data supplement that accompanies the online edition of this article.

Discussion

We found that in about 1 in 7 occasions when 188 remitted subjects completed the SCL-90 (73 of 514 assessments), relapse followed within the ensuing 6 months. This relapse rate is consistent with other reports (

6–

8). Relapses were associated with more, not less antidepressant treatment. Notably, these relapses were clinically meaningful because they were associated with a more severe and chronic depressive illness course over the next 5 years.

Among patients who had achieved remission from their previous depressive episode, we found a broad range of SCL-90 symptoms present at a moderate or worse level, including dysphoria (depression, anxiety, anger-irritability), sleep disturbances, somatization, and having one’s feelings easily hurt. The co-occurrence of anxious and depressive symptoms is common in major depressive episodes (

20), and it also seems to be the case in periods of remission, albeit with less severity.

Nierenberg et al. (

8), using a far less stringent definition of remission (a score <6 on the 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician-Rated [

21] for 7 days), also reported the presence of some depressive symptoms in remission. With an empirically valid 8-week period of full remission (

6), the present study showed that indeed some depressive but also other symptoms were observed in the period of apparent remission. These symptoms could have been either prodromal early expressions of the subsequent episode or residual symptoms of a prior episode or condition. In either case, our study indicates that they were useful for predicting depressive relapse over the ensuing 6 months.

Specific SCL-90 symptoms that most differentiated relapse from nonrelapse included symptoms of depression, anxiety, headaches (common in both anxiety and depressive disorders), and affective instability. These appear to reflect dysfunction in several CNS systems, including neurocognitive (feeling blocked in getting things done, trouble concentrating), psychomotor, and reward systems (feeling pushed to get things done, feeling low in energy or slowed down), the fear circuit (feeling tense or keyed up, worrying too much about things), and affective dysregulation or instability (crying easily, feelings being easily hurt). Despite having achieved full remission, patients who are more likely to relapse appear to remain in an unstable state that impairs the needed resilience to deal with the ups and downs of daily living. Consistent with the association between neurocognitive impairment and poorer acute treatment outcome (

22,

23), this impairment also seems to predict a worse prognosis in remitted depressed patients who relapse within the next 6 months.

Our results suggest that the more brain functions (circuits) involved, the greater the risk of relapse, which expands on the study of Nierenberg et al. (

8), who found that a greater number of residual depressive symptom domains after remission was associated with a greater likelihood of relapse within the next year.

Of greatest importance in this study is that we demonstrated, as a proof of concept, that it is possible to construct a brief self-report scale that can be used to ascertain an estimated risk of relapse for the individual patient. Such a person-level indicator can be used to tailor the follow-up schedule for each remitted patient based on his or her individually identified risk of relapse and potentially to initiate interventions in a more timely fashion when needed.

A simple count of the number of symptoms (0–12) self-reported at a moderate or worse level of severity during the past week created a score that was highly related to the risk of relapse. A score of 0 was associated with a low (5.8%) risk for depressive relapse in the next 6 months, suggesting that these patients may be managed by, for example, telephone visits at 3 and 6 months. Patients with a score of 6–9 had a 34.1% risk of relapse, and those with a score of 10–12 had a 72.7% risk of relapse; for these patients, more frequent follow-up contacts would be warranted to intervene at the first sign of symptom worsening. Thus, this 12-item scale appears to provide clinically actionable guidance for over half of the sample, which would seem to have cost efficiencies as well as therapeutic advantages.

This study has several limitations. First, the clinical decision tool that we devised must be viewed as hypothesis-generating. Replication in other samples is essential. Second, we did not include all possible sociodemographic and clinical variables that might affect relapse. We limited ourselves to the symptoms in the SCL-90 in order to explore the possibility of constructing a simple and feasible clinical tool that can possibly even be administered as a self-report assessment. Whether prediction from this tool could be enhanced by adding other easily acquired patient-level variables would be of interest. Third, generalizability may be affected by lack of heterogeneity in the all-white study sample, by the requirement that the analytic sample have no missing weekly depression severity ratings for 6 consecutive months following the SCL-90, and by changes in both the care systems and antidepressant medications since the study period (1978–1987).

In summary, about 1 in 7 fully remitted, formerly depressed patients experienced clinically meaningful depressive relapses over the next 6 months. These relapses were associated with a far worse course of depression over the ensuing 5 years. As a proof of concept, we have demonstrated that a brief 12-item symptom-based tool can provide an estimate of the risk of relapse for individual patients. Such simple, clinically based indicators can provide a platform onto which laboratory-based measures could be added to further personalize patient care.