T

o the E

ditor: We thank Dr. Susser and colleagues for their commentary on our article (

1) regarding the longitudinal association of depressive and anxiety disorders with leukocyte telomere length (LTL) in which they argue that the lack of depression- and anxiety-related differences in LTL shortening, as well as the finding of apparent lengthening in LTL over time, might be due to measurement error. We agree that this is a very timely and important topic to discuss, considering the increasing number of studies with repeated measures of LTL in longitudinal designs.

First, we would like to propose to use the term “measurement variation” instead of “measurement error” to address the issue of assay coefficient of variation. Measurement error suggests technical error was made in the assay, which is not the case. Assay variation, expressed as coefficient of variation, is an assay characteristic associated with any type of biological assay, and telomere length is no exception.

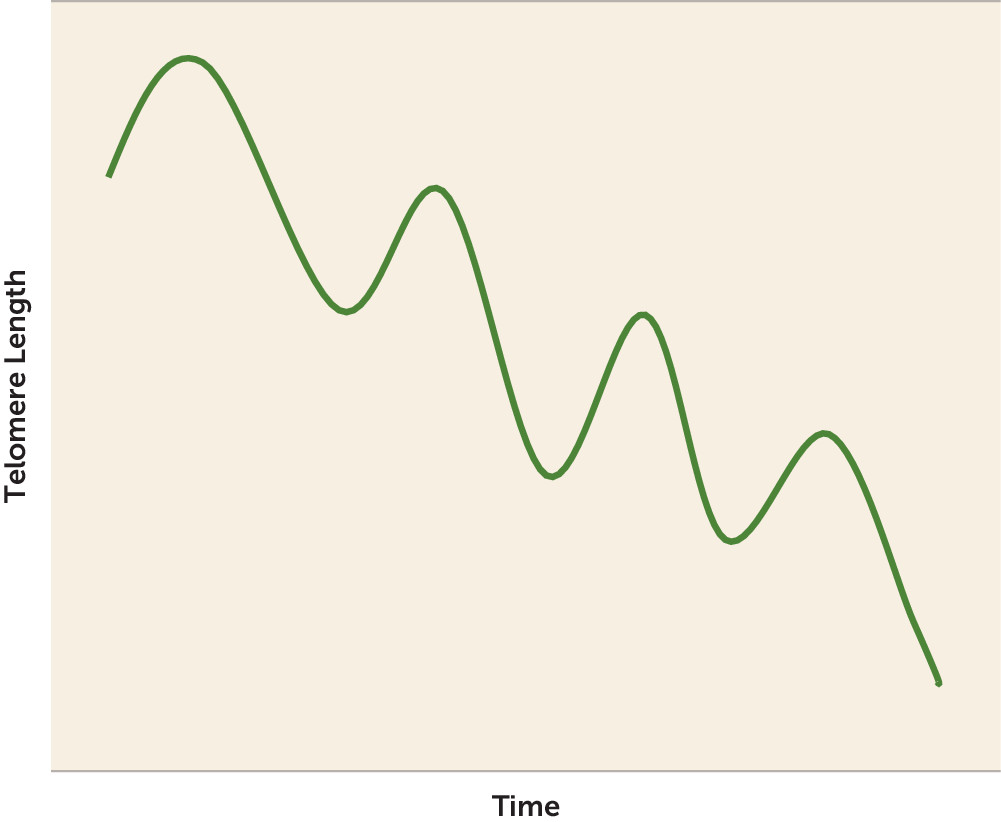

In the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA), 26% of participants showed apparent telomere lengthening over 6 years of follow-up. Longer follow-up periods in other studies indeed showed smaller proportions of lengtheners (

2). However, this long-term overall decrease in the proportion of lengtheners does not rule out the possibility of dynamic changes, as shown in

Figure 1. In fact, Svenson et al. (

3) reported this oscillating telomere length pattern across three different measurement methods: quantitative polymerase chain reaction, Southern blotting, and single telomere elongation length analysis. Therefore, we feel at this point that it is not possible to distinguish what proportion of the lengtheners in NESDA showed actual lengthening and what proportion was a result of measurement variation or, alternatively, differences in cell composition (

4). It is important to recognize that, next to measurement variation, there are several other feasible and nonexclusive explanations for the lengthening. In other words, the presence of measurement variation, while limiting interpretability, does not rule out the possibility of true lengthening.

Second, the average telomere shortening of 13.3 base pairs (bp) per year in NESDA is smaller than the assay coefficient of variation. However, there is a wide range of telomere shortening within the cohort, and it is the individual differences of change over 6 years, not the average shortening rate, that we are correlating with the depression- and anxiety-related variation. Naturally, the lack of longitudinal associations in our cohort does not preclude depression- or anxiety-related differences in LTL change in other longitudinal cohorts with different characteristics. Rather, we report this finding in our cohort, with the specifics associated with this cohort and its LTL assay conditions.

Furthermore, the comparison between the amount of measurement variation (SD=205 bp) and the average shortening (LTL change=80 bp) that Susser et al. make is somewhat misleading. Measurement variation adds to the observed variance of LTL, which is the sum of the true variance of LTL and the variance of the coefficient of variation. In NESDA, the average observed variance (including measurement variation) is SD=525 bp; consequently, a measurement variance of SD=205 bp implies that for the true LTL variance, the standard deviation is the square root of 5252−2052, or 483 bp. From this perspective, measurement variation increases the standard deviation, and hence the standard error for testing differences, by a factor of 1.1 (525/483). Needless to say, the increase in variance is unfavorable for testing differences in LTL change, but stating a 2.5-fold higher measurement variation than the average LTL shortening overestimates the coefficient of variation–related noise.

Third, the correlation between baseline and follow-up LTL in NESDA is indeed lower than the 0.91–0.96 as reported by Benetos et al. (

5). This could be a result of a number of factors, including measurement variation, different cohorts, and different time frames of repeated sampling. Importantly, we show (

1) that at both baseline and follow-up time points, short LTL is correlated with depression and anxiety disorders, validating the claim that short LTL is associated with depression and anxiety disorders in the NESDA cohort.

Fourth, applying the correction for regression to the mean suggested by Verhulst et al. (

6) to the NESDA data showed that the correlation between baseline LTL and LTL change decreased from r=−0.72 (p<0.001) to r=−0.17 (p<0.001). While this shows that statistical regression to the mean might indeed account for a proportion of the correlation, this also shows that the correlation remains significant when adjusted for regression to the mean, possibly as a consequence of the internal telomere homeostasis system (

7). Furthermore, applying the adjusted LTL change score to the analyses of Table 4 in our article (

1) did not change the results: changes in depression and anxiety characteristics were still unrelated to changes in LTL.

In summary, we argue that the results from the NESDA cohort are not solely due to measurement variation, but there is true variance in change to be accounted for as well. Nonetheless, the results raise important but unanswered follow-up questions on the phenomena of observed telomere lengthening and the interpretation of the association between baseline telomere length and telomere length change. We therefore strongly agree with the authors that aiming for studies involving longitudinal birth cohorts and high precision telomere length measures would be advantageous, and we look forward to continued dialogue.