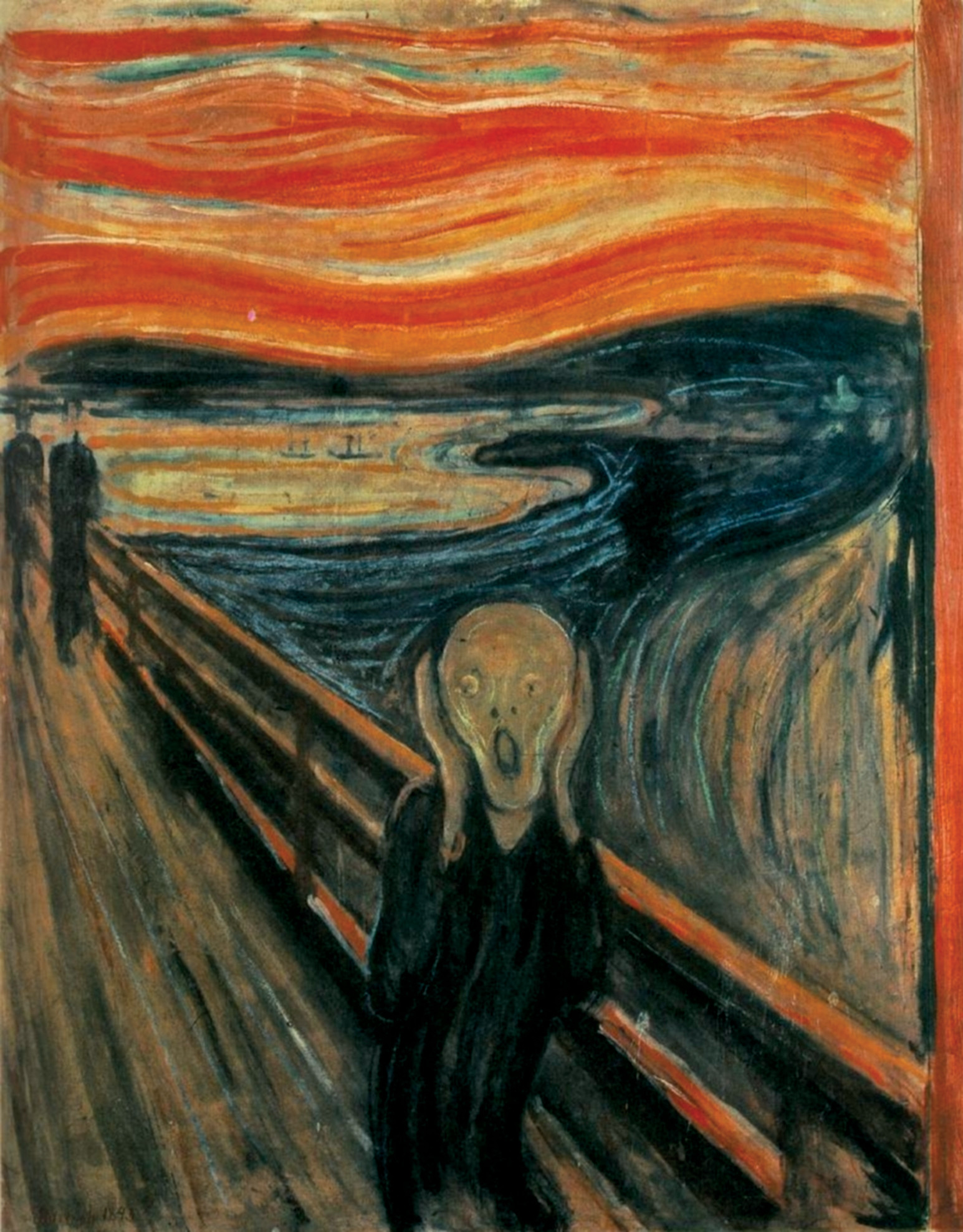

Painted in 1893 by the Norwegian artist Edvard Munch,

The Scream (original title:

Skrik) has become an iconic symbol of anxiety and uncertainty in the modern age, a sort of Mona Lisa of our time (

2). After becoming familiar with the symbolist sensibility of Paul Gauguin and the graphic outlines of Vincent Van Gogh, Munch moved to Berlin, where he laid the groundwork for modern Expressionism. He was one of the most prolific and creative artists of his time, and the first Scandinavian artist to earn an international reputation. During the Secessionist exhibition in 1902, Munch exposed an ambitious series of artworks, called the “Frieze of Life—A Poem about Life, Love and Death”: the true heart of his creative life (

3). The majority of Munch’s early works embraced pessimistic themes, such as death, anxiety, jealousy, and alienation. In his paintings, lonely and estranged individuals appeared alone, in pairs or groups, with scarce or ambiguous expressivity (

4); shadows and rings of intense color emphasized the atmosphere of fear, menace, or sexual intensity (

5). These images have been interpreted as reflections of the artist's anxieties and pessimism about human existence, developed after some tragic family events (

6): the premature deaths of his mother and older sister from tuberculosis during his childhood, his father’s delirious religiosity, and another sister’s schizophrenia (

3). Munch’s work was also strongly influenced by the philosopher Søren Kierkegaard and by the Norwegian playwright and poet Henrik Ibsen, who both acknowledged anxiety as an existential problem (

3).

The Scream is an extreme and extraordinary representation of Munch’s internal grief and mental condition, which led him to hospitalization in 1908 (

7). An important attestation about the uniqueness of individual perception of the disease can be found in his own words: “I was walking down the road with two friends when the sun set; suddenly, the sky turned as red as blood. I stopped and leaned against the fence, feeling unspeakably tired. Tongues of fire and blood stretched over the bluish black fjord. My friends went on walking, while I lagged behind, shivering with fear. Then I heard the enormous, infinite screams of nature” (

6). Munch was conscious that his mental instability was part of his genius, but after recovery he decided to abandon the chronic alcoholism that had exacerbated his tormented feelings, even provoking hallucinations and persecutory delusions (

8).

After his death in 1944, a collection of more than 20,000 artworks—including paintings, woodcuts, lithographs, and photographs—was discovered in his estate outside Oslo, where he lived for the last 27 years of his life in complete isolation. Today, Munch still remains famous for being the creator of a single emblematic image, which has obscured all the important achievements of his innovative and influential career (

2). Nevertheless, Munch was an acute explorer of human passions and emotions during his entire lifework, representing universal themes such as death, love, sexuality, and human vulnerability (

9).